by Stephanie Whitney

In the summer of 1939, documentary photographer Dorothea Lange traveled to the Yakima Valley to document migrant families and rural poverty for the Farm Security Administration. Lange's framing of her subjects and her captions revealed much about how rural poverty was seen as well as Lange's social commentary. "Migrant Woman, originally from Texas,Yakima Valley, Washington" by Dorothea Lange, 1939. Click photograph to enlarge. (FSA-OWI fsa 8b34285)

“Chronic rural poverty,” though present throughout and beyond the history of the United States, was significantly exacerbated during the economic downturn that characterized the Great Depression.[1] Widespread economic disaster influenced the nation’s farms so acutely that even early on in the Great Depression, in 1930, “approximately one third of all American farm families were living at a level that was comparable to…urban slum families.”[2] According to assessments of land use planners, by that time “more than 100 million acres of land in cultivation [on which] more than 65,000 farm families [resided] were…unsuitable for normal farming methods.”[3] Additionally, according to the same source, the economic collapse of the early 1930s had already impoverished “an additional one million farm families.”[4] In Washington State, the Yakima Valley represented one of the areas most impacted by the onset of the Great Depression.

Responsible for relieving a portion of these agrarian hardships, the Farm Security Administration came into being in 1937 when the Resettlement Administration—created in 1935 to combat the plague of “chronic rural poverty” that had spread across the United States as a result of the Great Depression—was transferred to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.[5] Rather than attempting to reach a standardized definition of poverty, the FSA perceived poverty in a more fluid sense—terming any set of conditions in which people fell “below the acceptable standard of living in a community” as “impoverished.”[6] Interested in identifying and subsequently eradicating the sources of acute rural hardship, the FSA differentiated between “case poverty,” caused by individual misfortunes like bad health or insufficient education, and “insular poverty,” defined as “an ‘island’ of poverty in which ‘everyone or nearly everyone is poor’” due to any number of circumstances affecting the area or region.[7] Although acknowledging that the two subgroups were often interrelated, the FSA specified early on their dedication to alleviating the poverty of those “farm tenants, sharecroppers, and migratory farm laborers who lived permanently below the generally accepted standards of living …for whom want had become a normal condition of life [and] the so called agricultural ladder…a fiction.”[8]

Whereas the grimy, crowded, slums of urban cities were impossible to ignore, poverty in rural areas such as Yakima was easier to overlook. Positioned at a distance from large population centers, and in a vast setting of natural beauty, the individuals suffering resided in less concentrated numbers than their urban counterparts, spread out across the enormous landscape and thus less obviously in need of help.[9] Identifying this, the FSA gathered and employed a handful of photographers to document rural living conditions with the intention of getting both an informational base for the Administration to work from and to educate the country about the impoverished conditions of these agrarian citizens in a way that simultaneously promoted the agency and its programs.[10]

Dorothea Lange, originally a portrait photographer for the social elite, began documenting the visible manifestations of the repercussions of the Great Depression when Lange was compelled out of her studio—both for ethical reasons as well as a decline in portraiture business—and into the streets of San Francisco to document “what was happening: homeless men sleeping on park benches, crowds lining up at relief stations, strikers and the unemployed demonstrating and sometimes even battling the police.”[11] In the summer of 1934, Lange’s redefinition of her professional identity was cemented when an exhibition of her street photographs attracted the attention of Berkeley professor Paul Taylor.[12] Shortly thereafter, when appointed as the Emergency Relief Administration’s field director for rural rehabilitation, Taylor insisted that “words alone could not convey the conditions,” hiring Lange to photograph what he documented in writing.[13] Taylor, later to become Lange’s husband, was instrumental to her career as a photographer. Not only did he provide her with an introduction to government via her collaborative work with him in the California State Emergency Relief Administration in 1935,but he also made sure subsequently that her work received recognition in Washington, D.C.—bringing her to the attention of the FSA’s Roy Stryker who, upon seeing her work, promptly offered her a place on his photography project’s team.

During the 1930s, “four systems of agricultural labor relations prevailed in the United States: family farming in the North and Midwest, sharecropping in the South, tenant farming on the southern plains, and migrant wage labor in the West.”[14] Lange’s work in Yakima thus centered on the living and working conditions of the families that currently resided in the area, with an emphasis on families receiving support from rural rehabilitation programs in the form of “loans and technical assistance in farm management and home economics.”[15] Her photographs and accompanying captions documenting the lives of these families are explicitly thoughtful, balancing favorable commentary on the positive results of the FSA’s programs with subtle critiques and portraits of the hardworking lives of these families.

This Lange photograph and its caption, "All Chris Adolf's children are hard workers on the new place," portray the rural Adolf family as hardworking and deserving of federal support. 1939 by Dorothea Lange. Click on the image to be taken to this image in an archive of Lange's photographs. (FSA-OWI fsa 8b34284)

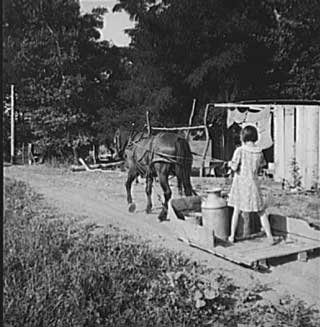

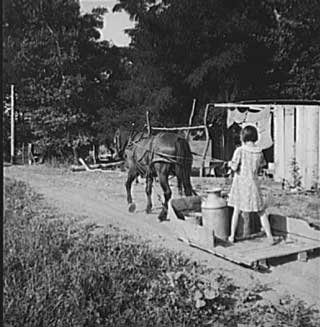

The pictures available in the Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information archive that Lange took of the Adolf family in 1939 are an excellent example of her method. Whereas some of the photographs are apparently meant to display what the family has been able to attain with the help of the FSA—a team of horses, land, and housing as well as the less substantive benefit of an apparently healthy, well-cared-for family (photograph 44)—other images provide a subtle commentary on the tenuous nature of their relative success.[16] A second picture depicts one of the younger Adolf girls perched atop a sort of wooden sled harnessed behind one of the family’s newly acquired horses (photograph 50). She is standing with her legs braced apart for balance, holding the reigns against her body, seemingly on an errand for her parents transporting the various containers positioned in front of her. The short accompanying caption reads: “All Chris Adolf’s children are hard workers on the new place…Farm of Rehabilitation Administration borrower.”[17] Here, Lange carefully balances portraying the family as hard working and deserving of federal support (in harmony with FSA publicity objectives) with an subtle commentary on the nature of a childhood dominated by manual labor.

Lange’s depiction of the Arnold family was similar in portraying the success of FSA programs as well as the challenges migrant families still faced. Describing their context and recent history in a handful of short paragraphs in ‘general caption no. 36,’ Lange effectively preserved their living conditions through her photographs and brief text. Like the Adolf family, the Arnolds were supported by the FSA during the 1930s, specifically participating in the “Non-Commercial Experiment” (helping to minimize individual’s land debt and/or standard rehabilitation loans).[18] Her photographs of the Arnolds capture the epitome of FSA ideals: in one print the family is shown removing leftover “debris, roots and chunks” from the field where a bulldozer had just previously removed a number of heavy stumps for burning.[19] Everyone in the family is suspended in motion in the photograph, save for the smallest boy, who, taking a brief break from his work (his cheek is smudged with dirt, his hand resting somewhat wearily on his hip) stands upon a dirt pile amidst the action watching the camera thoughtfully, resting against a tall stick.

The general caption furthers the photograph’s depiction of a hardworking family, noting how Mrs. Arnold was “unwilling to have any photographs made in or even around the house, which was messy and unkempt [, explaining] that she was unable to attend to household affairs properly because she put in all her time ‘on the place.’”[20] The caption simultaneously reveals the family’s intentions to further better themselves, quoting Mrs. Arnold’s plans for a “‘nice house, with a porch across the front.’”[21]

Lange's portrayal of the Schrock family near Wapato, Washington, assures us of their responsibility, home-ownership, and close family ties. Click on the image to be taken to this image in an archive of Lange's photographs. (FSA-OWI fsa 8b34377)

A second photograph illustrates the hardworking but tenuous existence of Lange’s subjects. Capturing a moment not often depicted in FSA photography, the image shows the Arnold children posing for the camera along with creature comforts purchased with money that they earned working.[22] One child stands on either side of the bike that the eldest bought with his earnings, each child holding onto a handlebar. Slightly to the side stands their barefoot younger sister holding a small cat. These two photographs powerfully evoke the message of the FSA: to raise rural citizens out of chronic rural poverty. Lange’s photographs depict a quintessential rural American family that managed, with the help of the FSA and through their own hard work, to not merely survive but to achieve a comfortable standard of living.

In order to garner public support for their efforts to alleviate the suffering of farm families, the FSA promoted outdated agrarian ideals such as those Thomas Jefferson had advocated, privileging the rural citizen and country “folk” as “quintessential” Americans through their emphasis of outdated small-town imagery.[23] As historian Linda Gordon argues, the department sought to depict agriculture as the “only truly moral way to secure wealth and happiness,” thus reflecting a “nostalgic yearning for restoration of traditional institutions, such as subsistence agriculture and the family farm.”[24] Since such a representation of rural families as living “simple…community-spirited” lifestyles was outdated and inherently at odds with plantations and industrial agriculture, the FSA sought to detract attention from this inconsistency by emphasizing the aspects of these outdated ideals that corresponded to American ideas of small-town simplicity, rural living, and limited luxury.[25]

Lange’s three photographs of the Schrock family in the Yakima Valley illustrate this emphasis on small-town American values and simple luxuries, as well as the models for success portrayed by the Adolf and Arnold families. The first picture (photograph 57) depicts the typical farm family assembled outside the home, Lange’s caption reading:

"Washington, Yakima Valley, near Wapato. One tenant purchase program (Farm Security Administration) client, Jacob N. Schrock. This family with eight children had lived for twenty-five years on a rocky, rented farm in this valley. They now own forty eight acres of good land, this good house, price six thousand seventy hundred and seventy dollars. They raise hay, grain, dairy and hogs. Mrs. Schrock says "Quite a lot of difference between that old rock pile, and around here.”"[26]

Through the caption, Lange creates a positive connotation for the way the family is perceived, using simple, down-home terms such as “forty eight acres of good land [and a] good house.” Even though the voyeur can only see a portion of the side of the house, Lange’s caption assures them that what they can’t see in the photograph—the rest of the house, the forty eight acres of land, the crops and farm animals etc.—is both present and directly beneficial the family.

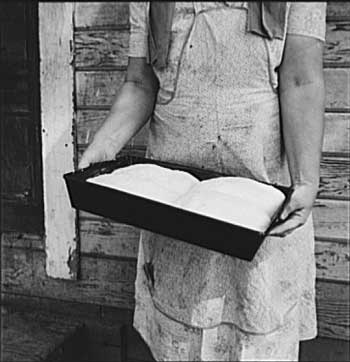

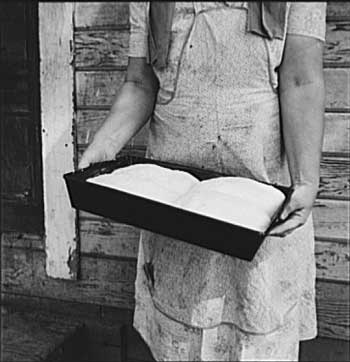

Mrs. Schrock's bread loaves speak to her industry, her particular form of harvest, but was also cropped by Lange as a more abstract work, rendering Mrs. Schrock's work, not Mrs. Schrock, as the documented object. (FSA-OWI fsa 8b34301)

Dissimilar to the typical family images previously explored, Lange’s second two photographs of the Schrock family are more abstract. One of the photographs presents a cropped shot of Mrs. Schrock outside of her home holding a pan of what appears to be four uncooked loaves of bread (photograph 27).[27] The caption to the photograph reads quite simply: “Mrs. Schrock takes good care of her family.”[28] What sets this photograph apart from the others, however, is the visually rhetorical nature of the crop. Rather than depicting the entire family assembled around the material indicators of their success, by cropping the photograph to only show Mrs. Schrock’s torso and pan, Lange renders Mrs. Schrock as an archetypal housewife, not a poor migrant. We do not see the Schrock’s poverty but only their wealth here. Another photograph depicts no one in the Schrock family at all, rather just a segment of their kitchen (photograph 38).[29] Multiple objects in the photograph mark the Schrock’s financial success: sheer ruffled curtains, a hanging plant, a kitchen timer, a number of loaves of bread, and a large bag of sugar—by extension suggesting a successful FSA program helping to generate such luxuries.

Although Lange’s images of FSA clients represented a large portion of her photographing responsibilities in Yakima Valley, it must not be overlooked that she was also there to document the conditions of the valley itself and the conditions experienced by those residing in the valley at the time of her exploration. A vast number of her photographs where thus dedicated to documenting the lives of (and problems experienced by) migrant farm workers.

One photograph Lange took in the valley at first glance depicts a mother and her children next to their tent (photograph 68).[30] However, when the photograph is read with its caption, the differences between this family and the FSA client families previously photographed become clear. An acute social commentary, the caption describes how the family had just arrived in the valley from Minnesota, that they had no father figure to speak of, that they were living behind a gas station out of a tent, and that the mother was working in 106 degree and hotter weather picking pears to try and support herself and her three children. The photograph naturally raises questions about the absence of any sort of subsidized housing for migrant workers (which was exceedingly scarce at the time), and raising larger questions of how families could survive by migrating from single crop harvest to single crop harvest.

Other photographs depict similarly improvised living conditions, documenting “homes” ranging from makeshift houses and tents constructed with whatever materials were available to minimalist shacktown communities (photograph 19, 82).[31] Particularly interested in the livelihood of the people living in such provisional housing, Lange dedicated a considerable amount of energy to the documentation of the field laborers’ work.

This picture of a pear tramp is part of Lange's documentary work, implicitly commenting on the working and loving conditions of migrant workers. Click on the image to be taken to this image in an archive of Lange's photographs. (FSA-OWI fsa 8b34679)

When Lange visited Yakima Valley in August of 1939, one of the main fruits in season was the pear. Subsequently, she took a number of photographs of migrant workers harvesting the fruit, carefully recording the ins and outs of the process in her captions. In the caption for one of her portraits taken of a “fruit tramp,” Lange focuses on the satchel that the laborer carries the picked pears in, directing attention to the design of the “pear strap, to balance weight of the pears” (photograph 41).[32] In her general caption for the pear harvesting of 1939, Lange also attentively documented the workers’ wages (30 cents per hour) as well as the “special skills [needed for] the picking and the handling of pears” such as balance and agility for navigating ladders and between branches.[33] Her work here seems largely documentary, but is a subtle form of social commentary, specifying the working, living, and social conditions of migrant workers’ lives through words and pictures.

However, despite the relative individual successes of FSA clients and the wealth of information preserved through the prints produced by the photographic project, various conflicts between FSA ideals and popular Depression-era ideas about the poor prevented the extended support to rural clients that Lange and the FSA had hoped. The prevailing mentality of poverty as an individual moral failure subverted the FSA’s attempts to define poverty in more structural terms. And despite Lange’s careful documentation of the success of FSA clients, the idea persisted that accepting relief from the FSA meant “sign[ing] that you [were] not worth anything.”[34] Thus, with American involvement in World War II drawing near by 1940 and the fear of communism spreading, the program that had “enjoyed a measure of acceptance or acquiescence” during the difficulties of the Great Depression came to be viewed increasingly as an Administration in conflict with the “cultural preferences and social values on which political legitimacy rests,” losing power throughout the 1940s until it was ultimately replaced by the Farmers Home Administration in 1946.[35] Yet despite the ultimate failure of the FSA and Lange to win the wide-scale social reforms that they advocated for, Lange’s photographs of the Yakima Valley stand testament to the history of migrant farm labor during the Depression and the vision of social change that the Arnolds, Adolfs, and Schrocks portrayed.

Copyright (c) 2010, Stephanie Whitney

HSTAA 353 Fall 2009

[1] Baldwin, Sidney. Poverty and Politics. University of North Carolina Press: Heritage Printers, Inc., 1968. 3.

[2] Baldwin 38.

[3] Baldwin 104.

[4] Baldwin 104.

[5] Baldwin 3.

[6] Baldwin 21.

[7] John Kenneth Galbraith quoted in Baldwin 21.

[8] Baldwin 21, 22, 170.

[9] Baldwin 23.

[10] Godron, Linda. "Dorothea Lange: the Photographer as Agricultural Socialist." Journal of American History 99:3 (2006): accessed online, 25 Nov 2009, http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jah/93.3/gordon.html, p. 17.

[11] Gordon 15.

[12] Whiston Spirn, Anne. Daring To Look: Dorothea Lange's Photographs and Reports From the Field. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008. 16, 17.

[13] Whiston Spirn 16, 17.

[14] Gordon 5.

[15] Whiston Spirn 188.

[16] "FSA-OWI: Dorothea Lange Yakima Valley." American Memory from the Library of Congress. Library of Congress, Web. 25 Nov 2009. <http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/fsahtml/fsaPlaces48.html >.

[17] FSA-OWI.

[18] Whiston Spirn 199.

[19] Whiston Spirn 202.

[20] Whiston Spirn 199.

[21] Whiston Spirn 199.

[22] Whiston Spirn 201.

[23] Gordon 7.

[24] Baldwin 22, 268.

[25] Gordon 7.

[26] FSA OWI.

[27] FSA-OWI.

[28] FSA-OWI.

[29] FSA-OWI.

[30] FSA-OWI.

[31] FSA-OWI.

[32] FSA-OWI.

[33] Whiston Spirn 156.

[34] Baldwin 22-23, 275.

[35] Baldwin.