by Kaegan Faltys-Burr

Seattle's jazz culture flourished in the 1920s and 1930s, particularly in the multiracial neighborhood culture of Jackson Street in Seattle's Central District. Jazz musicians in Seattle, c. 1925. From left to right, Leon Hutchinson, John Slocum, Glover Compton, and Frank Waldron. (Photo courtesy of the University of Washington Special Collections)

On June 10, 1918, Seattle saw its first local jazz band perform in Washington Hall, at 14th Avenue and Fir Street. Miss Lillian Smith’s Jazz Band played to raise money for the NAACP and officially opened Seattle’s local jazz scene.[1] Although Washington Hall held many shows, the heart of Seattle jazz was just southeast at the corner of 12th and Jackson Street: according to historian Paul de Barros, “[t]his is where Seattle jazz was born and where it flowered.”[2]

During the Great Depression, there was no time to reminisce about the excess of the Roaring Twenties—it was a time to look forward. As a musical style and as a social movement, jazz embodied this forward looking spirit. Seattle’s jazz scene weathered the Depression well and managed to maintain the vibrant musical scene that had developed in the area in the decades before the economic crash. Jazz on Jackson Street provided an environment where Seattleites of all races and classes could come together to enjoy themselves during the hard economic times of the Great Depression. Jackson Street jazz musicians also took their craft overseas and while entertaining international crowds, some learned a thing or two.

Building a Home for Jazz on Jackson Street

Jackson Street became the hotbed for Seattle’s jazz scene primarily because of its proximity to the Black community and because of the underground nightclub scene that developed during the Prohibition years. A steady stream of immigrants and migrants swelled Seattle’s population from 3,533 in 1880 to 80,671 in 1900. During this period, Yesler Way represented the dividing line between the more “respectable” parts of Seattle to the north, and the newly settled Yesler-Jackson community to the south. Previously the site of lavish Victorian homes, by 1890 Yesler-Jackson had an abundance of third-rate hotels, shops, bars, and brothels, which made the area decidedly lower-class. It was also the official destination for Seattle’s growing immigrant and migrant populations.[3]

Despite the best efforts of authorities, Seattle remained "wet" during Prohibition, which allowed underground nightclubs, and thus jazz, to flourish. Here, King County Sheriff Matt Starwich destroys bottles of confiscated alcohol, ca. 1925. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Library Digital Collections.)

Seattle’s Black population numbered only 406 in 1900, but the following decades saw a sharp increase in Black migration. Although Blacks were never the racial majority in the Yesler-Jackson neighborhood, the area housed much of Seattle’s Black population, which numbered 2,894 by 1920.[4] Black migrants brought with them jazz and musical traditions from around the country and, by the 1910s, Seattle’s “culture of legalized corruption…supported venues for music.” Prohibition, which began in Washington in 1916, prompted the need for underground clubs and speakeasies and city officials were all too eager to look the other way—and even encourage vice—upon receiving cash payment.[5] Though Seattle’s jazz scene was still in its infancy, the city’s lenience toward illicit clubs allowed them to grow into what would become the future home for jazz on Jackson Street.

The unique political and social climate of Prohibition and 1920s Seattle nurtured the rapid growth of the city’s nightlife and Jackson Street’s many clubs. In 1917, local entrepreneurs Russell “Noodles” Smith and Burr “Blackie” Williams opened the Dumas Club at 1040 Jackson. A few years later, in 1920, Smith and Jimmy Woodland open the Entertainers Club at 12th and Jackson. With the nightlife heating up by 1922, in the basement of the Entertainers Club Smith and Williams “christened” the Alhambra, which became know as the Black and Tan by 1932 and would become a hot spot for Seattle jazz during the Great Depression.[6] While Jackson Street was always the heart of Seattle’s jazz scene, the nightlight extended to semi-legal “roadhouses” (freestanding nightclubs located on the outskirts of town) where alcohol and jazz flowed freely. Together, the roadhouses and the Jackson Street night clubs embedded jazz in Seattle’s nightlife and “[b]y 1928, jazz had taken over the popular music scene.”[7] Clubs continued to pop up on and around Jackson Street—the Blue Rose (later called the Rocking Chair) on 14th and Yesler and the Chinese Garden’s Club (aka the Bucket of Blood), across from 511½ 7th Street South—and even when the stock market crashed and the Great Depression hit, there was no doubt that jazz would remain on Jackson Street.

Jackson Street During the Depression: Racial Mixing and Police Raids

If the 1910s and 1920s firmly ensconced jazz in Seattle’s nightlife, the Depression era showcased the unique power of jazz music to bring people of all races and classes together. It also let the city see and hear the evolution of jazz on Jackson Street. According to local jazz pianist Palmer Johnson, in the 1920s we played “[n]o Dixieland and no two-beat…That’s old-time stuff. It was jazz man.”[8] And it was jazz that made Jackson Street famous. This is what the Northwest Enterprise, a Seattle based African American newspaper, had to say about Jackson Street in the midst of the Depression in 1933:

"[I]t attracts persons from all sections of the city and numerous migrants who are attracted by the bright lights and other allurements. And there are allurements, if you know where to find them…Jackson Street might well be called the ‘Poor Man’s Playground.’ Here all races meet on common ground and rub elbows as equals. Fillipinos [sic], Japanese, Negros and whites mingle in the same hotels and restaurants and there is an air of comradeship."[9]

As the above excerpt suggests, Jackson Street was a unique part of Seattle’s nightlife and jazz was one of its “allurements.” Although the Northwest Enterprise did not mention jazz clubs explicitly, one could call Jackson Street’s jazz scene the catalyst for racial mixing and comradeship. Indeed, historian Quintard Taylor remarks that the Jackson Street clubs “were the only places where well-to-do white businessmen and socialites met black and Asian laborers and maids as social equals.”[10] While the musicians on Jackson Street were mostly Black, they played for crowds of whites from all over the city as well as for Blacks and Asians.[11] Carlos Bulosan, the Filipino American novelist and poet, remembered that noisy jazz music kept him awake as a child while he stayed in a rundown hotel on King Street, the heart of Seattle’s Filipino community.[12] Bulosan’s memory is testament to the presence of a Filipino community just a block away from Jackson Street, illustrating the multiracial—as well as musical—character of the Yesler-Jackson community.

This multiracial character was partly a product of what Quintard Taylor calls Seattle’s “admittedly benign racial environment.” While there is no doubt that racism and discrimination were widespread, they did not have the “harsh, caustic edge” seen elsewhere in the country.[13] This allowed Black migrants, Asian and Filipino immigrants, and whites to interact with relatively few conflicts. Nevertheless, some Seattleites—particularly upper-class whites—disapproved of the abundance of vice and racial mixing on Jackson Street. Prompted by distaste for vice, as well as their own racist sentiments, city officials and police began to take action against Jackson Street clubs’ illicit activities, and police raids increased during the Depression.

The Odean Jazz Orchestra, c. 1925, probably playing downtown at the Nanking Cafe. (Photo courtesy of the University of Washington Special Collections and the Black Heritage Society of Washington State)

By 1933 the Alhambra nightclub, owned by Noodles Smith and Blackie Williams, had been renamed the Black and Tan and business was booming. Located on 12th Avenue South and Jackson Street, it was know as Seattle’s “most esteemed and longest lived nightclub,”[14] and was later the inspiration for Duke Ellington’s famous short film and tune Black and Tan Fantasy. Smith owned numerous nightclubs during the 1920s and 1930s, for which Taylor dubs him the “impresario of black nightlife.” The Depression hit everyone in Seattle—but not Smith. He owned both a Stutz Bearcat and a 1921 Packard and his ostentatious lifestyle likely offended many in such hard times, especially racist whites who cursed the success of Black entrepreneurs.[15] After the repeal of Prohibition, the police sometimes ignored the illegal practices (such as gambling) of most Jackson Street clubs. But police raids were common, and highly visible club owners like Smith attracted more attention from the often racist police institution.

On Sunday September 10, 1933, county constables raided the Black and Tan. The Northwest Enterprise reported on the raid the following Thursday:

"In what was purported to be a gambling raid, four constables from the Morningside precinct engaged in a battle royal with employees of the Black and Tan Club, 12th Ave. S. and Jackson Street early Sunday Morning…Finding no evidence of gambling two constables said to have been under the influence of liquor, began abusing the employees by cursing. Suddenly the lights went out and a battle ensued in which the county officers were roughly handled…Not satisfied with their raid Sunday morning and incensed by the beating they received, two of the constables returned to the club Tuesday night and assaulted Lem Turner, colored bystander outside the club…The raid and actions of the constables has caused city wide condemnation and is generally regarded as an attempt to shakedown the sporting district for graft money."[16]

The fact that it was the police who first started “abusing” employees at the Black and Tan, which then led to the ensuing “battle royal,” suggests that the police came with malicious intentions. The unprovoked beating of Len Turner by police two days later helps to confirm this suspicion.

While police raids were a constant annoyance, they rarely had lasting negative effects on popular clubs like the Black and Tan. Moreover, because public opinion generally sided with the club’s owner and patrons, raids created sympathy and sometimes additional patronage for Jackson Street night clubs. After the 1933 raid, the Black and Tan was operating at full capacity in no time, supplying Seattleites of all sorts with jazz and other “allurements.” Even repeated police raids and arrests could not shutdown a club with the popularity of the Black and Tan. A year later, the Northwest Enterprise reported another Sunday morning raid, this one on December 30, 1934:

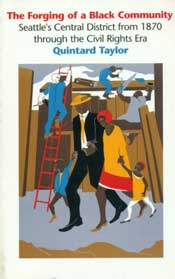

Dr. Quintard Taylor's book, The Forging of a Black Community, chronicles Seattle's Central District and Jackson Street community from 1870 to the 1960s.

"State liquor law enforcement officers staged a spectacular raid on the Black and Tan Cabaret, 12th Ave. and Jackson Street, early Sunday morning to the discomfort of 200 guests. The raid marked the fourth on the popular pleasure resort for 1934…E. Russell (Noodles) Smith, owner, Henry Nelson, assistant manager, four musicians and five entertainers were arrested together with thirty-two guests and taken to jail where all were released on bail…The raid had no effect on the cabaret as the resort has continued to operate every night since."[17]

Clearly, police raids were a common occurrence. Yet despite his arrest the previous morning, Black and Tan owner Noodles Smith had the club open that very evening.

In the midst of the Great Depression and plagued by racially targeted police raids, the resilience of Jackson Street’s jazz clubs like the Black and Tan is remarkable. But is it not so surprising: as local jazz pianist Julian Henson put it, Seattle “was a town-and-a-half, man…Nothing happening ‘til after twelve o’clock, then it came alive. All night people running from club to club. It was an after-hours circus.”[18] This positive view was no doubt held by many—though clearly not all—Seattleites of the time. The unique racial makeup of the Jackson Street area and the political context that “licensed” illegal activity made Jackson Street, as the Northwest Enterprise claimed, the city’s “playground.”

Seattle Jazz Goes International

Seattle’s jazz scene thrived but showed some marked differences from jazz elsewhere in the country. In places like Kansas City and New York during the Great Depression, the style of jazz and the makeup of the jazz band were changing. In early jazz styles, all band members played together around one simple melody and jazz bands usually consisted of four to ten members, called “combos.” The Depression era saw early jazz styles evolve into a more complex “swing style,” where particular parts of the band traded off playing melodies one after the other, in a call-and-response pattern. To facilitate this musical exchange within bands, jazz bands got bigger—often times with twenty members or more—and became know as “big bands.”[19]

Edythe Turnham and her Knights of Syncopation, c. 1925. Turnham toured the Northwest with her band and played up and down the West Coast and on President Line Cruises, embodying travel routes that linked Washington musicians to the rest of the nation and the country. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Library Digital Collections.)

Although the new swing style of jazz quickly caught on in Seattle, very few (if any) local big bands were present during the Depression, though popular big bands from around the country performed in Seattle regularly.[20] According to historian Paul de Barros, the absence of local big bands was a product of two factors. First, Seattle had a very small Black population, with about 3,500 Black residents out of about 366,000 in total.[21] This led to a correspondingly small number of Black jazz musicians available to form big bands. Second, there was a lack of high-paying venues to support local Black big bands because Seattle’s wealthy downtown nightclubs were for whites only.[22] While the popular national names like Duke Ellington and Count Basie could get work in the wealthy all-white clubs, local musicians were usually barred. The lack of high-paying venues for local Black musicians in Seattle had two additional effects: it helped concentrate jazz on Jackson Street and led some local musicians to search for work elsewhere.

One example was local jazz pianist Palmer Johnson, whose contribution to Seattle jazz spanned fourteen years. Johnson was born 1907 in Houston but raised in Los Angeles. As a child, L.A. exposed him to the sights and sounds of the budding Jazz Age and the music stuck in his memory. Johnson started playing music at age seven and was playing professional jazz gigs by 1924, only ten years later. In November 1928, Johnson made his way from California to Washington in search of opportunities to play music, and found them on Jackson Street. Local jazz musicians encouraged Johnson to develop his skills and nurtured his passion.[23] From then on, Seattle was home for Johnson and he found little shortage of work in Jackson Street’s many jazz clubs and in the roadhouses outside of town—that is, until the depths of the Depression.

Johnson first left Jackson Street in 1934 for greener pastures in Portland, Oregon, another west coast jazz city. While there, he made good money, but Seattle band leader Earl Whaley convinced Johnson to quit the Portland scene and join a band he was taking to Shanghai, China. During the Depression, Shanghai was home to many wealthy internationals which created demand for the latest U.S. craze: jazz music. Jazz musicians could make $100 to $200 a week playing in one of Shanghai’s many nightclubs, which made the trans-Pacific trip quite lucrative. Johnson stayed in and around China for the next three years, returning to Seattle in 1937.[24] Even the Northwest Enterprise took notice of Johnson’s extended vacation:

"A letter from Palmer D. Johnson tells of the success in Shanghai, China, of the colored band organized in Seattle last summer to fill engagaments [sic] in the Orient. The boys left Seattle in July and reached Shanghai in September where they have been a big hit at St. Anans [sic] Cabaret, largest pleasure resort in the Chinese city…Mr. Johnson describes Shanghai as a cosmopolitan city with representatives of every race in the population. The most rude mannered and impolite of all races, he says, is the American white man. Johnson says the Chinese call them “crazy men.”"[25]

Johnson’s letter gives a sense of the unique opportunity for jazz musicians to play in Shanghai and the social critique of American society the experience prompted. Johnson claimed that in the multiracial milieu of Shanghai, the “American white man” was the most ill-mannered, a claim that most Chinese agreed with. Many Black jazz musicians said that while playing in Shanghai “they were treated with respect for the fist time in their lives.”[26] Accustomed to living under racial segregation in the United States, it is not surprising that Black jazz musicians felt they received more respect and more freedom in the cosmopolitan city of Shanghai. But what is most interesting is the explicit criticism of the “American white man” as ill-mannered and “crazy.” Few (if any) Blacks during the Great Depression supported racial segregation, but it was the law. It seems that jazz music gave Johnson the opportunity to experience a society where racial differences were much less important and formulate critiques of the prevalent mentality of white superiority in the U.S. This transformative experience in China afforded through jazz music is indeed remarkable.

The Great Depression Winds Down as the Jazz Scene Heats Up

For Jackson Street local and jazz pianist Palmer Johnson, what was intended to be a few months stay in Shanghai, ended up as a three-year adventure in which he played for bands in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Singapore. Upon his return to Seattle in 1937, Johnson found Jackson Street as alive as ever with a number of new clubs quickly gaining in popularity. President Roosevelt’s New Deal cash infusions put money into people’s pockets, which created demand for nighttime entertainment. There was a rapidly growing clientele for the up-and-coming nightclubs like the 411 Club at 411 Maynard Avenue South, just past Jackson Street; the Green Dot at 809 Jackson Street; the Ubangi at 710 7th Avenue South, a few blocks south of Jackson Street; and the Two Pals, the Congo Club, and the Black Elks Club as well.[27] Clearly, the Jackson Street jazz clubs had only continued to multiply during Palmer Johnson’s extended absence.

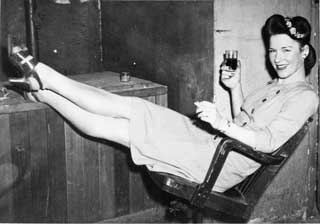

Jazz singer Wanda Brown arrived in Seattle in 1943 and emceed and sang at The Garden of Allah nightclub and other clubs in Seattle into the 1990s, signifying the continued vibrancy of Seattle's jazz scene after the Depression. (Photo courtesy of the University of Washington Special Collections)

In the climate of Roosevelt’s New Deal, Jackson Street jazz clubs began catering to more class-specific audiences. Noodles Smith, owner of the highly successful Black and Tan, saw the need for a more sophisticated club to satisfy the growing demand of wealthy whites for jazz venues. With this in mind, Smith opened the Ubangi club sometime after 1935 and according to Paul de Barros, it was “one of the Jackson Street district’s most successful and glamorous black-owned nightclubs.”[28] The Ubangi had exquisite African themed décor, complete with potted palms, and it boasted two large stages, one on each of its floors.[29] Smith spared few expenses, flying in musical and dance acts from Los Angeles, and as a result most of the patrons attracted to the club were white. But even the lavish Ubangi continued to deal with problems of police harassment. And sadly, the Ubangi only operated for a few years before it closed in 1938 when the building was sold.[30]

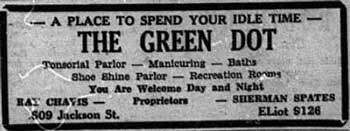

Another nightclub to flourish during the New Deal period, more characteristic of the gritty Jackson Street jazz scene, was the Green Dot. Roosevelt’s cash infusions put money in everyone’s pockets and the Green Dot was just the place for Jackson Street’s and Seattle’s lower-income residents to enjoy jazz music. A barber shop by day and a jazz parlor by night, the Green Dot took advantage of advertising space in the Northwest Enterprise to get the word out during the New Deal boom in jazz’s popularity. A small text ad from 1934 reads:

A newspaper advertisement from January 11, 1934 for The Green Dot jazz club, and less formal and very popular establishment on Jackson Street. From the Northwest Enterprise newspaper. Click the image to see the full newspaper page.

"A PLACE TO SPEND YOUR IDLE TIME

THE GREEN DOT

Tonsorial Parlor — Manicuring — Baths

Shoe Shine parlor — Recreation Rooms

You are Welcome Day and Night."[31]

The informal atmosphere of the Green Dot attracted numerous patrons from around the Jackson Street and Seattle areas and was an ideal compliment to the glamorous, upscale, Ubangi.

While the Great Depression was ending, the swing era of jazz was just beginning. Jackson Street nightclubs like the Green Dot, the Black and Tan, and the Blue Rose (soon to be renamed the Rocking Chair) continued to operate into the 1940s and 1950s and Jackson Street remained the heart of Seattle’s jazz scene. The swing era attracted new listeners to jazz music, particularly young people. As swing developed, Seattle’s youth danced to big time jazz names like Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Woody Herman, and Gene Krupa, as well as to the local Jackson Street jazz musicians.[32] Some of these big names even appeared in Jackson Street’s nightclubs.[33] As swing gained in popularity, the Jackson Street clubs could no longer hold the swelling crowds and jazz spread throughout the city. But Seattle jazz will always have its roots in the jazz clubs of Jackson Street.

A Final ‘Rap’ on Jazz on Jackson Street

The Yesler-Jackson community with its strong Black population and Seattle’s social and political context of legalized corruption provided the perfect atmosphere for jazz to grow and thrive. Jazz musicians and clubs came and went—Palmer Johnson went all the way to China while the Ubangi club just went under—but Jackson Street remained the heart of Seattle jazz for many years after the Great Depression. Although when compared to more prominent jazz cities like Chicago, New York, or New Orleans, Seattle’s scene was small, it had its own special character. The racial and social mixing seen on and around Jackson Street was remarkable in an era of racial segregation and class tensions. The proximity of Seattle to Asia also gave Jackson Street musicians the unique opportunity to travel and perform internationally. And the relatively small size of the Jackson Street jazz scene allowed the musicians, club owners, and club patrons to develop a sense of community. In the end, Jackson Street should be remembered not only for its jazz music, but also for its ability to bring diverse peoples together.

Copyright (c) 2010, Kaegan Faltys-Burr

HSTAA 353 Fall 2009

[1] Paul de Barros, Jackson Street After Hours: The Roots of Jazz in Seattle, (Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 1993), 10.

[2] Ibid., 1.

[3] Quintard Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era, (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994), 34-35.

[4] Ibid., 108.

[5] de Barros, 1-2.

[6] Ibid., 3.

[7] Ibid., 12-17.

[8] Palmer Johnson, “Interview with Paul de Barros and Jim Wilke,” 20 November 1988; 16 October, 23 October, 4 November, 26 November, and 17 December 1989. Transcripts, University of Washington Manuscript Collection.

[9] “Jackson Street is Quiet Thoroughfare On Sunday,” Northwest Enterprise, 12 October, 1933, p.1.

[10] Taylor, 148.

[11] Ibid., 147.

[12] Carlos Bulosan, America is in the Heart, (USA: Originally published by Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1943; reprinted by the University of Washington Press, 1973), 99-100.

[13] Taylor, 154.

[14] de Barros, 3.

[15] Taylor, 147.

[16] “Country Constables Raid Black & Tan Night Club,” Northwest Enterprise, 14 September 1933, p.4.

[17] “State Liquor Offices Raid Black and Tan,” Northwest Enterprise, 3 January, 1935, p.4.

[18] Julian Henson, “Interview with Paul de Barros,” 20 January, 1991. Tape Recording, University of Washington Manuscript Collection.

[19] de Barros, 38-29.

[20] Ibid., 39.

[21] Taylor, 108.

[22] de Barros, 42-43.

[23] Ibid., 17-20.

[24] Ibid., 47-49.

[25] “Seattle Colored Band Is Success In China,” Northwest Enterprise, 31 January, 1935, p.4.

[26] de Barros, 47.

[27] Ibid., 43.

[28] Ibid., 41.

[29] Taylor, 147.

[30] de Barros, 45.

[31] “Ad for ‘The Green Dot,’” Northwest Enterprise, 11 January, 1934, p.4.

[32] de Barros, 50.

[33] Taylor, 147.