In a front page article published February 26, 1931, the Kitsap County Journal declared "Business not so bad in Kitsap." The county had its share of bankruptcies, but many businesses survived and even expanded during the Depression. Indeed, out of 39 counties in Washington State, only 8 had payroll gains in 1929, and Kitsap was one of them.

During the 1930's, the world economy suffered a severe financial collapse known as the Great Depression. In the United States, communities from Maine to Washington State faced dire conditions, with many families unable to secure even the basics like food and shelter. Some places, however, were able to temper the Depression's worst impacts by relying on th strength of local industries, which could operate with some independence from national and international markets. Kitsap County, in the Puget Sound region of Washington State, was one such location. Although it did not remain completely untouched by hardshaip, the combination of a substantial natural resource base and a successful businesses community allowed the county to maintain a relativel stable economy throughout the early 1930's.

At this time, the Kitsap County Journal (Journal) was the primary source of local news for Bainbridge Island, Kingston, Poulsbo, Silverdale, Bremerton, and Port Orchard. It reported on everything from U.S. Supreme Court issues to the price of bread. A review of its pages offers a unique snapshot of the social, political, and economic climate of Kitsap County during the early years of the Great Depression (1929-1932) and is the basis for this research report.

Surprisingly, the articles, advertisements, and commentaries in the Journal do not offer a large amount of information on the everyday effects of the Great Depression within the county. National affairs, especially politics, received substantial attention, as did the activities of the U.S. Supreme Court. Journal commentators wrote many general pieces on the economy that encouraged patience, advised the unemployed, complained about ineffective government, and discussed new taxes. The slow progress of legislation intended to aid the needy and the 1932 presidential election also got considerable notice, with the largely Democratic citizens of Kitsap County excited by Franklin Roosevelt’s victory. Yet there were virtually no articles about the local economy of Kitsap County. Why was this? Was Kitsap County really so unaffected by the economic crisis that it could only observe the plight of surrounding areas? Was it an effort to boost the morale of readers by not focusing on hard times? From reading between the lines, some clues do come out that offer an explanation for the lack of information about local conditions.

From 1929 to 1932, the Journal consistently reported the price of common household groceries, such as bread, milk, eggs, coffee, and the like. Surprisingly, during the early years of the Great Depression (1929-1932), the expected fluctuation in prices is not evident. The price of flour, for example, stayed constant at $1.89 per sack for nearly the entire period. Only once does the price dip 5¢, indicating that the bread supplier, Pilot, may not have suffered from the tumultuous economy, nor were its customers affected by a drop or rise in price.[1] The consistent pricing of much-needed groceries and other staples suggests a parallel consistency in the economy of Kitsap County.

Likewise, the price of automobiles advertised in the Journal stayed relatively constant - $435 for a Ford “Open Roadster” in 1931 and $460 in 1932. [2] The pattern repeats for the majority of cars sold from 1929 to 1932 in the Kitsap County area. This example is especially helpful in providing a picture of the relative economic stability of the region. In 1930, there was even a recorded increase to 3,742 cars on the road in Kitsap County.[3] Was Kitsap County immune to the recession, or were there aspects of the local market that the newspaper did not print?

Several businesses in the Kitsap County area survived the Great Depression, though some did have to lay off workers. Based in Seattle, Puget Sound Power and Light Company helped boost employment in the entire region. The company received the Forbes Trophy in 1928 “in recognition of the excelling service rendered to its customers and for the part which it has taken in the agricultural and industrial development of the territory which it serves.”[4] The Journal published numerous advertisements and articles about this business, including notices calling on the unemployed to apply for various manual labor jobs in its multiple locations around Kitsap County.[5] In 1932, the company announced that it would be significantly reducing its budget and service prices to accommodate the lagging economy. [6] As the Depression worsened, such foresight could have been what saved it from going bankrupt.

Puget Sound’s natural resources, including productive farmland and vast timber reserves, also boosted the economy. An advertisement titled “Clear Land for Profit” appeared in the Journal a few times in 1928 and even more often after the stock market crash in 1929. The ad outlined the state’s need for cleared land, described how to remove trees and brush with dynamite, and even how to sell the wood for payment. It was an easy way to make a few bucks off local timber. [7] The cleared land could provide space for crops, pasturelands, and new homes. According to one article on the matter, “Too many settlers never see the back fence for the brush and trees that hide it, and the sooner they let the sun shine on more of their farm land the more profitable their farm operations will be. Larger farms mean larger incomes.”[8]

One prominent local business, the Chas. R. McCormick Lumber Company, would pay cash for local families’ produce, sometimes allowing the trade of farm products for lumber materials. It was a direct way for famers to obtain the means to expand their operations. The company would then resell the produce for a profit. In cases such as these, however, it was possible for cunning businesspersons to take advantage of local impoverished farmers.[9] Lumber was also in demand when Kitsap County Transportation Co. took on the task of building two new ferries for the Puget Sound and British Columbia waterways. Bids went out for local wood and steel companies to supply the necessary parts for the new ferries. [10]

Farming and agriculture also contributed to local economic well-being. Poultry, dairy, beef, produce, and wheat products contributed $146,894,700 to the state’s revenues in 1929, a 5% increase from the previous year.[11] Kitsap County bulls were worth $51.19 a piece in 1931, compared to the statewide average of $28.70. The “dairy cattle in Washington [were] setting a word’s record for income...”[12] This figure is evidence of the healthy market for beef in the region.

The Puget Sound region shipped its dairy products “by boat to Alaska, Hawaiian Islands and foreign countries,” which boosted its economy during the Depression.[13] National Egg Week, a nation-wide event that encouraged Americans to eat more eggs in order to bolster the market, held special importance in Kitsap County, as “there [were] no industry that lends itself so readily in Kitsap County conditions as the poultry business… with its thousands of acres of cut-over lands, needing just this sort of development.”[14] Bremerton Creamery & Produce Company Inc. advertisements appeared monthly in the Kitsap County Journal throughout the duration of the Depression. The year 1929 set a record for revenue generated by wheat, dairy, fruit, and poultry.[15] Even a year into the Depression, the turkey industry, was “making rapid strides in Kitsap County” in 1931.[16]

The dairy industry of Kitsap had its fair share of assistance from the Bremerton Chamber of Commerce. In 1931, the chamber met to discuss a competing dairy brand, Carnation, and the detrimental effects its uncommonly low prices were having on local farmers. Carnation dairy products sold for “60% below the customary retail price,” which “is demoralizing to the trade of local manufacture and distribution.” The Chamber condemned this, stating, “Fair competitive conditions and fair prices are essential to the welfare of local producers, manufacturers and merchants, and of vital interest to all citizens of the community.”[17] Released to the public, the statement also made its way to Carnation and, eventually contributed to a slight increase in the town’s dairy prices, allowing for equal competition with the Kitsap dairy farms.

The dairy industry accounted for a significant portion of Kitsap County's economic activity in the early years of the Depression. It is not surprising then that the Bremerton Chamber of Commerce sought to take action to prevent the sale of uncommonly inexpensive products from Carnation, Washington.

Another booster of dairy sales came through the Washington Dairy Products Bureau, which started a campaign in 1931 to increase statewide awareness of the health benefits of dairy, and consequently expand the market of milk and cheese products. Local dairy companies, taking “1/10¢ per lb. on all butter-fat produced in the state,” sponsored the campaign. They produced booklets, posters, radio ads and school programs to raise awareness and promote the healthful, yet non-fattening, qualities of milk products. Dairy products would “bring under-weight people up to normal and keep them there.”[18] This campaign resulted in even higher milk consumption and dairy exports in 1932. [19]

In February 1931, the Washington State Senate passed a 15¢ per lb. tax on butter substitutes in order to raise money to clear more land for dairy farms, and thereby increase dairy production. The Senate’s plan was to add some 35,000 additional cows to Washington herds, resulting in 3,500 new dairy farms and 85,000 jobs. “This will make the Washington dairy business the greatest of any state in the Union,” according to the article. Because Washington exported butter to the East Coast, the tax did not much effect the price of the product. “The rise and decline of butter prices are not governed by any such legislature, but by supply and demand alone.”[20] This tax no doubt boosted the dairy production of Kitsap in the following years as more land moved into dairy pasture. In this case, the Washington government was not afraid to think ahead - even during a time of economic depression.

Other agricultural products proved economically important as well. These included ginseng and golden seal, two plants exported to China, where their roots and leaves had high value as medicine.[21] Also significant was the cannery industry. Washington canneries showed an increase in profits in 1929, with fruit production falling off a bit, but the difference being more than made up for by vegetable production, worth $11,500,000 in revenue for the state.[22] At the height of unemployment in 1932, a cannery actually opened in Bremerton, beginning “a series of meetings…between the farmers and the businessmen of Bremerton” in order to bring about communal profit using the natural resources of the area. The canning of local beans and corn began in the following weeks.[23]

In January 1930, the Bremerton Farm Congress met in Bremerton to discuss possible ways to increase farm efficiency and improve general conditions for farmers. They shared their personal methods of production and collaborated with struggling farmers to help them increase output. The farmers’ willingness to help and cooperate with each other is evidence of their strong sense of community.[24] Kitsap County’s rich farms and pastureland provided stability for the broader community during the Great Depression.

A significant hub of reliable employment in Kitsap County at this time was the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton. The government-run base kept hundreds of men off the streets and softened the blows of the economic collapse. The following is a telegraph sent from the Bainbridge Island Chamber of Commerce to their congressional delegation:

"Numbers of our residents are employed in Navy Yard Puget Sound at Bremerton. Some of them are laid off [on] account [of the] lack of work there…. The Bainbridge Island Chamber of Commerce therefore urges you to use every effort to secure Battleship modernization contracts for this ward and speed up work in Cruiser Astoria to prevent further layoffs and to stabilize employment, which is so vital to Kitsap County."[25]

Senator Wesley L. James and John F. Miller assured their efforts to create jobs for Kitsap:

“I assure you that everything I can do here to expedite matters and to keep employment up will be done. When the legislation is through for the modernization of the battle ships one of them, at least, should be modernized on the Pacific Coast, and no yard is better equipped to do that than the Puget Sound Yard.” [26]

In 1930, the annual payroll of the shipyard was $6,619,947.45, “every dollar of which [was] new money in this area” (meaning that the money was from the government; not from local circulation). In addition to bringing “new money” to Kitsap County, the food purchased to go to the Navy Yard and onboard the ships were all products of the Pacific Northwest. Canned milk, butter, eggs, fish, fowl, meats and vegetables came in bulk from Washington farmers to boost the local economy.[27] By 1932, the Bremerton Chamber of Commerce reported that the shipyard was working to full capacity, with the addition of the U.S.S. Arkansas to “undergo an overhaul,” and would surely remain so for the rest of the year. [28] The Puget Sound Naval Shipyard even offered apprenticeship opportunities for high school graduates, who were unable to afford college tuition.[29] The annual “Navy Day” Celebration was an important social and economic event for Kitsap, drawing nearly 10,000 people from all parts of the state. Guests got tours of the Navy Yard, watched boat races in the Sound, received awards for competitions, enjoyed over 100 floats in a massive parade and marveled at a fireworks display over the Bremerton harbor. [30]

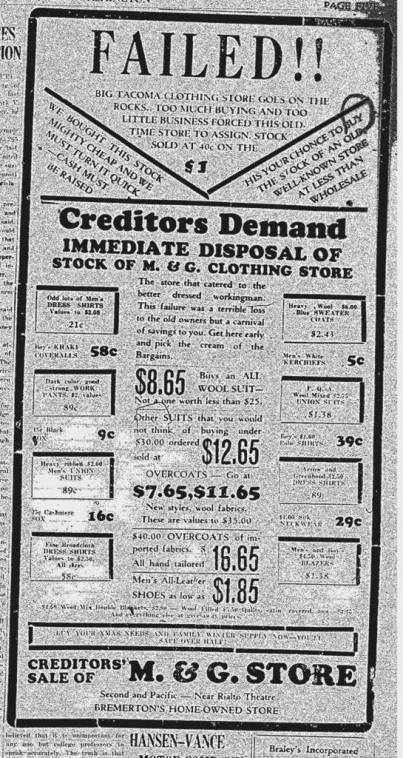

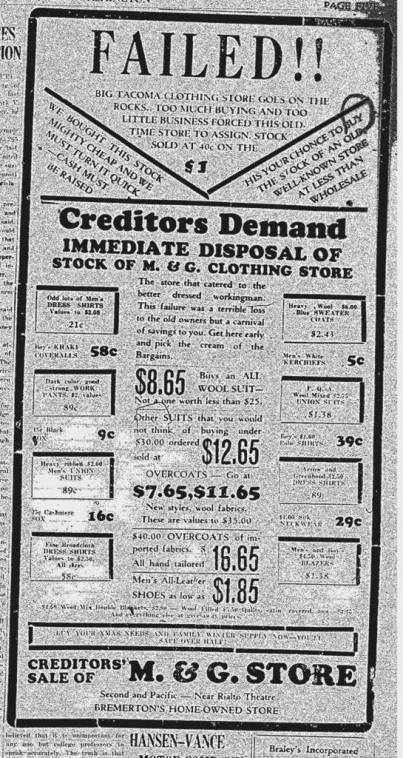

Obviously, not all businesses prospered during the Depression. In 1930, two large clothing stores in Kitsap County went bankrupt due to “too much buying and too little business.”[31] M&G Store and The Fashion both went out of business and were forced to sell to the US Bankrupt Court.[32] In 1931, Bremerton’s Emergency Relief Committee announced its contributions in helping nine unemployed men find work, as well as its monetary relief to a few local businesses and unions, including the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Letter Carriers Local 1414, and the Laborer’s Union, totaling $346.04. [33] The Journal published an article a month later containing a list of all Kitsap citizens (about 100) receiving unemployment relief from the Emergency Unemployment Bureau. [34]

Not all businesses could survive the Depression. In 1930, two large clothing stores in Kitsap County went bankrupt due to “too much buying and too little business." Above, a creditors' sale for one of the stores is announced in the Kitsap County Journal.

Leisure activities continued to be popular in Kitsap County during the early years of the Depression. In nearly every edition of the Kitsap County Journal, Foster’s Pavilion advertised its weekly dance nights open to the public for a small price. It also put on special events during the holidays and other times, such as Masquerades and picnics. The events usually featured orchestras, fine food and prizes.[35] The Kitsap County Fair continued to be an important event for the community as well, featuring horse races, carnival attractions, dog shows, and produce competitions. [36] The Stojowski Piano Colony, another entertainment oriented organization, appears in numerous ads for music concerts of local musicians and singers, with admission for 75¢. [37] The Orthopedic Hospital in Squamish held an annual benefit bridge luncheon, often drawing 200 benefactors to enjoy an afternoon of card games and prizes.[38] Even at this difficult moment, people evidently had the money to sponsor local hospitals.

the Garden Clubs of Washington rallied citizens to beautify their towns, opposing advertisements that “mar landscape along our scenic roadways

.”[39] Other articles in the Journal discussed popular exterior finishing on homes and even how to detail a car.[40] The “Better Homes Week” program featured an event in which women would travel from home to home, eating courses of a meal and discussing decor and garden improvements for the homes they visited

. [41]

Bainbridge Island (and Kitsap County more generally) was a wealthy community relative to the rest of the state even before the financial crash. Its Chamber of Commerce hosted bi-annual banquets during the early years of the Depression to inform the public of their activities. The banquets were lavish events featuring live music and entertainment, oftentimes feeding upwards of 400 guests. The Eagles Band and Ladies Auxiliary held an annual picnic on Bainbridge, offering airplane rides for a fee, sea-sledding, free dancing, and refreshments, all for a slight admission fee. [42] During this same period, the Journal also reported that local residents were increasingly becoming members of country clubs. The allure of a quiet respite appealed to the upper-middle class of Kitsap County, and Island Lake Park County Club profited from it. [43] From these and other news items, it is clear that Kitsap County citizens harbored concerns and interests that went well beyond the financial crisis.

Several local community projects boosted employment in Kitsap during the Depression. In 1929, the Lateral Highway Act passed, which imposed a 1¢ gasoline tax for improvement of the nation’s highways. In January 1930, Kitsap was the first county in Washington to be given contracts to begin work on its roads. The county received $27,650 for improvement on Seabeck Road. Later that month, the State Highway proposed $11,500,000 be spent on grading and resurfacing the miles of highway between Silverdale and Keyport, and the Navy Yard Highway to the Pierce county line. [44] The following September, the Olympic Peninsula Development League met to start a new project - an Olympic Loop Highway across the Olympic Peninsula. Kitsap County proposed paving from Bremerton to Silverdale, giving the unemployed in the area a chance to work

.[45]

Another local project taking shape at this time was the opening of a cooperative chick hatchery for area farmers. The benefits for the farmers in this kind of arrangement were quite significant: eliminating both costly advertising and middlemen/salesmen. The cooperative would also get rid of the need to ship chicks across the state, which was very expensive. The co-op. would be “controlled entirely be local poultry men.... and to be so organized as to permit only part of the yearly revenue to be applied on the investment, and at all times to hold the selling price to members, below the regular market, making an immediate return.”[46] The hatchery was an excellent idea to create even more profit to poultry farmers in their already flourishing business.

In the 1930’s, Pacific Northwest tourism began to pick up and Kitsap County jumped on the opportunity to draw travelers to spend time and money in the area. After returning from a tour of the East Coast, W.C. Mumaw, Director of Washington State Chamber of Commerce, remarked, “Washington must meet this competition…or we will suffer seriously in comparison, in spite of the fact that we have superior resources and advantages.”[47] This inspired a “Tell the World about Washington” campaign, which involved stamps, posters, and radio ads inviting travelers to visit Puget Sound. Slogans promoted apple and lumber production, scenic wonderlands, improved roads, even a longer life in the Pacific Northwest. The Chamber of Commerce encouraged tourists to write to them to “know all the facts.”[48]

The lack of information on the effects of the Great Depression on the Kitsap Peninsula is intriguing. After a careful review of the Kitsap County Journal from 1929 to 1932, there appears to be little evidence of serious poverty in the county. While bankruptcies did occur, many Kitsap businesses survived and even expanded during the Depression. The United Press reported in 1931 that Kitsap was among only 8 counties (out of 39 total) in Washington State that experienced payroll gains in 1929.[49] It is not likely that the newspaper chose to minimize the impact of the Depression; when has that ever been the goal of news coverage? Rather, it seems that many companies in the Pacific Northwest knew how to stay afloat even during the most difficult of times. They used local resources and created jobs by starting new projects in the midst of economic crisis. Perhaps today’s businesses could learn from the strategies of depression-era companies to persist and recover from the current economic recession.