by Kiyomi Nunez

Mark Litchman risked his reputation and his safety defending members of the IWW, beginning with a case in 1918.The years of the Great Depression were a time of civil unrest and suffering for many people as they experienced job loss, economic turmoil, and fought for better living and working conditions. The latter struggle was especially evident in the lives of millions of workers, as working conditions and wages seemed to get worse and impossible to alleviate when employers themselves were feeling the loss of financial prosperity that was indicative of the Great Depression. And through all of this hardship, the people who were struggling the most to make change had little help to turn to. But in Washington State, where a labor movement was growing to combat worsening working conditions, a beacon of light in the form of lawyer shone through the darkness to help fight the uphill battle that the Great Depression presented for workers’ rights. This lawyer’s name was Mark M. Litchman and he would come to covet the title given to him— the most loyal defender of the “outcast and downtrodden” in the Pacific Northwest.[1]

Many of Litchman’s defenses of unions, their individual members, and leftist political groups awarded him little or no financial gain.[2] But Litchman’s deep commitment to the labor movement rang true, for he valued the gratification of helping his fellow man over the monetary rewards of winning legal battles. For this reason, Mark M. Litchman was an oddity of a lawyer during a time when financial stability was certainly one of the more important goals to American people. But this is not to say that Litchman didn’t also make great contributions ins ecuring civil liberties and workers’ rights during his early legal career and the pre-Depression era. His accomplishments before the Great Depression are also worth discussing here. But during a time that was so desperate, Litchman’s commitment to social justice made him one of the most inspiring figures in the labor movement and an insurer of the intrinsic American values of freedom, liberty, and justice for all.

Mark M. Litchman was born in New York City in 1887 to a family that had strong beliefs in the Jewish faith.[3] Litchman began work at an early age as a newspaper boy on New York City’s Lower East Side. Teenage Litchman’s lust for adventure and travel tempted him, in 1902, to lie about his age and enlist into the US Navy as a naval apprentice just seven days before the Navy fought to put down the Philippine Insurrection. This, in effect, made him the youngest veteran of the Philippine-American War, which could be said to be one of his first major accomplishments.[4] After his discharge from the Navy in 1903, he led a nomadic life in search of work and new places to visit. He mostly stuck to sailing and maritime jobs, sailing from one European port to the next, always in search of whatever work was available.[5] But his travels exposed him to many different kinds of people and living situations and gave him valuable experiences in the struggles of working people. In a letter to a childhood friend in 1934, Litchman stated, “My tramps over land and sea [have] given me both a heart and viewpoint for the underdog, and my early ideal…was to become a lawyer for the downtrodden.”[6] And so it was that Litchman began looking for a law school that would suit his needs, which ultimately led him to Seattle.

Litchman first came to Seattle in 1908 to begin studying law at the University of Washington, and graduated in 1913. The University of Washington’s Law School first attracted Litchman because of its free tuition.[7] But it was also Seattle’s history of labor movements and leftist ideals that attracted Litchman to the Pacific Northwest.[8] Litchman passed the Bar Exam for Washington State and opened his own law office in 1915. As one of his first major cases, Litchman attacked the Tuition Fee Law, which imposed tuition on students at the University of Washington in the Litchman v. Shannon case.[9] In this case, Litchman argued idealistically that a tuition fee imposed a discriminatory burden on the poor, though he ultimately lost the case. The Industrial Relations Commission’s report of that same year presented a study of the relationship between education and poverty, which used some of Litchman’s arguments from Litchman v. Shannon. Litchman’s argument in the case shows the beginnings of Litchman’s deep philosophical views that the American education system privileged some and not others, which in Litchman’s mind was linked to the question of working-class civil rights.[10]

Early in his legal career, Litchman represented and defended numerous unions, including the dominant union federation, the American Federation of Labor, and the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and their individual members who were fighting for union recognition, wage increases, hour decreases, compensation, and other issues in Washington State courts.[11] One of his first labor cases involved representing an IWW member charged with vagrancy in Raymond, WA in 1918. This case was tried at the local Commercial Club. Litchman argued that there was an obvious agenda at the Club to intimidate him and “the poor wobbly” that he was defending by having many prominent lumber employers testify against the defendant. Additionally, the club had packed its seats with nearly one hundred American soldiers who were employed as a scare tactic.[12] But using his keen understanding of the lumber industry and the law, Litchman attacked the employers of the lumber workers for refusing to go on an eight-hour workday as requested by President Wilson in the Adamson Bill of 1916 that created an eight-hour workday for railway train employees. Litchman reported that this trial had a great effect on local lumber workers, inspiring them to become “apostles” of the eight-hour workday.[13] And two weeks after Litchman’s defense, the eight-hour day became an established policy in the lumber industry of the Pacific Northwest. Litchman credited himself with “materially contributing” to the establishment of an eight-hour workday in logging camps because of this case and his other work in defending lumber workers.[14]

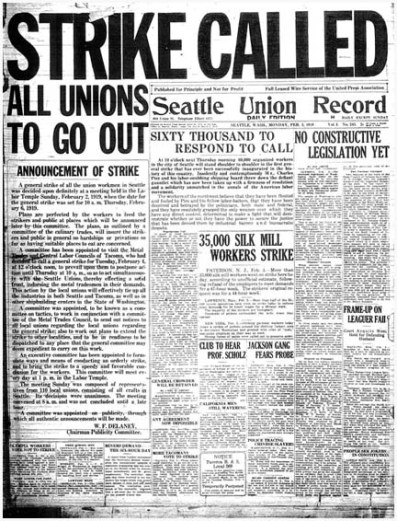

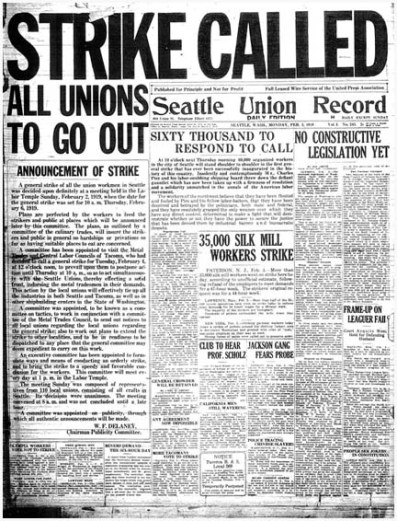

The Union Record was the official voice of the Seattle Central Labor Council from 1904 to 1928. To learn more about the the famous newspaper click the image.Litchman’s fight for the underrepresented spoke to his membership in the Socialist Party in Seattle. He believed that Socialism aimed for the empowerment of the less fortunate and especially for the workers of the world,[15] which is something he strived every day to accomplish in his legal and intellectual affairs. Litchman in fact had a membership and donor card to the Socialist Party of Seattle, as well as a certificate verifying that he had bought shares in the capital stock of the Socialist Publishing Association of Seattle.[16] And in letters to his family, Litchman admitted that he was a Socialist, but that he was more interested in “getting things done through legislation” rather than in strikes, because it was his duty as a lawyer to do things in a more legal and legitimate way.[17] In a letter to a friend, Litchman spoke of himself in his earlier legal career as being a “day and night soldier in the revolution” of Socialism by lecturing and writing about it, and practicing its ideologies in law.[18]

Litchman went on to defend several Socialists in cases of political discrimination and gained notoriety for helping to legally ensure free speech rights.[19] He also defended foreign-born radicals against punitive deportation charges during the Red Scare of 1919 and after the Seattle General Strike of that same year.[20] Litchman’s activities in Socialist circles and his legal career marked by social activism attracted the attention of the Seattle Union Record, a local socialist-oriented newspaper. The paper hired him as its attorney in 1919 after Litchman returned from serving as a U.S. Merchant Marine in WWI.[21] The Seattle Union Record was being charged with sedition by the government under the Sedition Act of 1918, which made it illegal to speak or agitate against the government, and had had its editor and other employees arrested and the production of its paper temporarily shut down. Litchman was able to successfully defend the Seattle Union Record against these charges of sedition and represented the paper in several later cases brought by the newspaper to deal with the local Postmaster, who wanted to deny circulation of the paper.[22]

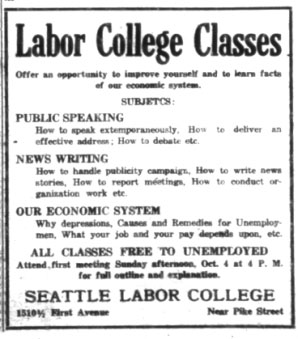

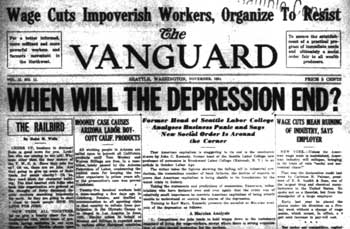

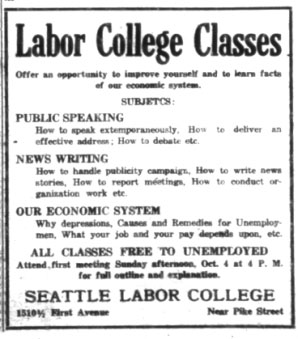

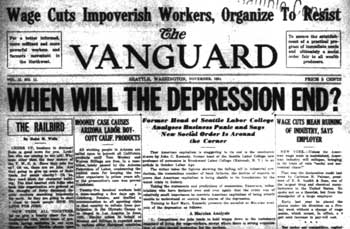

Litchman served as the first President of the Seattle Labor Council. This notice appearned in the Vanguard October 1931.Because all of his legal and social activism centered on the labor movement, it made perfect sense for Litchman to help organize and establish the Seattle Labor College, which he did in 1921.[23] The College offered free courses on various social issues and academic subjects like political science, economics, and law. UW professors and other community leaders taught these courses every Sunday night. Litchman also taught at the College, and gave numerous lectures, in addition to being the College’s first President from the years 1921 to 1923.[24] Litchman spent just as much time advancing intellectual causes as he did advocating and defending labor causes. He once wrote to a friend saying, “My wife, Sophie, and I have always been students” when describing the weekly “open house” for intellectual residents of Seattle that he and his wife held in their own home. Here, Litchman and his wife would host weekly lectures, readings, and discussions on current intellectual and labor issues, in addition to the classes and lectures at the Seattle Labor College. Litchman was especially compelled to teach about the labor movement and its history because he felt that “ignorance enslaved the minds of workers” and that education would “remove the shackles” and ultimately improve the lives of everyone.[25] But sometime in 1923, Litchman began to break his close ties with the Socialist and labor movements after a scuffle he had with the Communist Party of Washington State.[26]

As the president of the Seattle Labor College, Litchman was asked in 1923 by the Communist Party in Washington to host a meeting for the benefit of Communist members who were recently arrested in Michigan. Litchman was fearful of being labeled a Communist, as the Labor College had already been labeled as a Communist College, which he felt narrowed the larger focus of the College to aid the entire labor movement, not just one party.[27] Litchman himself was wary, as he didn’t agree entirely with Communist ideas. But even though he declined to host the meeting, Litchman did still volunteer to act as a chairmen and speaker at the event. After the meeting was held, Communist members offended Litchman by refusing to eat with him, something that was customary after meetings of that nature. Then, later that year, the Labor Temple Association, which consisted of Communists, threatened Litchman and his College with a labor boycott because of his defense of a smaller labor union that was fighting for its entitled money from the Labor Temple.[28] But Litchman, now harboring animosity toward the Communist Party, fought back and continued to defend the smaller labor union and ending up winning the owed money from the Labor Temple. This resulted in Litchman being barred from admission and speaking in the Labor Temple, as well as Litchman’s College being barred from holding any future meetings and classes there.[29]

After resigning in 1924 from his position as President of the Labor College, Litchman began to describe himself as “an average lawyer,” as he took on cases of businesses, employers, and of the middle class as opposed to working-class and radical issues.[30] Litchman was growing increasingly tired of the brooding distrust that radicals felt towards lawyers, even though the legal knowledge of radical lawyers was critical for their own legal defense.[31] He blamed the “ideological dogmatism” of leftist parties that saw lawyers as outside the working class as the cause of radicals’ suspicion of lawyers.[32] Moreover, it was common knowledge among lawyers during that time that defending labor radicals and workers’ rights meant risking one’s reputation not only as a lawyer, but as a dutiful citizen as well.[33] And yet, Litchman was still willing to defend the underrepresented and those who could not pay entirely for his services and advance civil and labor rights when he could.

In addition to handling the educational program for the Seattle Bar Association from 1925 to 1930,[34] Mark M. Litchman also took on an important labor case in 1925 that served as a precedent for an even more substantial 1926 labor case involving compensation for longshoremen.[35] In the primary case of Hartwood Lumber Company v. Alto, Litchman, working for the respondent side, was able to successfully argue that dockworkers, or longshoremen, should be brought under the same accident liability coverage as the seamen they worked with, guaranteed for seamen under the Jones Act of 1920. The legal language in the Jones Act semi-excluded longshoreman in its protection rights, but had become more encompassing of all maritime workers.[36]

Litchman used this decision as precedent when he represented the defendant in the International Stevedoring Co. v. Haverty case.[37] In this case, the plaintiff, a longshoreman, claimed that he was injured when a load of wood that he was attempting to stow on the hold of a ship toppled onto him due to the negligence of the supervising officer of the ship. Litchman won this case, arguing that the Jones Act and the Federal Liability Act covered all maritime workers, including longshoreman, and gave them the right to collect damages from their employers based on the negligence of any of their coworkers.[38] The defendant company then took the case all the way to the United States Supreme Court in Haverty v. International Stevedoring Co. Here, the Stevedoring Company argued that the Fellow-Servant Doctrine should be applied, which would prevent employees from receiving damages from the employer if an injury was caused by the negligence of a coworker or supervisor.[39] But Litchman continued to override employer’s efforts by arguing that the Jones Act extended the right to obtain damages from employers to all maritime employees, with the Hartwood Lumber Co. v. Alto decision serving as precedent.[40] Furthermore, Litchman was able to point out that with the 1915 Osceola Dictum and other similar cases, Congress had established that a seaman in command could not be considered as a coworker of those under him, especially those under him who have to rely on his direct performance to ensure their own safety.[41] Therefore any supervisor or coworker in command had responsibility for injuries sustained by employees, denying them the title of “a fellow servant.” Litchman concluded his arguments by saying that the Fellow-Servant Doctrine should not apply in this case or any future cases, as it was unconstitutional to fragment workers in the same industry, giving injury claim privileges to some, and not others, and that the current legislation then makes the doctrine null and void.[42]

The U.S. Supreme Court agreed with Litchman’s arguments, and awarded his client damages from the Stevedoring Company.[43] Litchman later claimed that this case completely abolished the Fellow-Servant Doctrine and was indirectly responsible for the passage of the Federal Compensation Act for Longshoreman.[44] This was a major accomplishment for Litchman, because it was a substantial victory for the labor movement and workers’ rights across whole industries. Although this would be Litchman’s only case that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, it certainly wasn’t the most significant for the labor movement’s history, at least not in Litchman’s view. Labor cases like these and others that Litchman took on gave him a renewed invigoration for helping the cause of the labor movement, which became imperative when the Great Depression began to take its toll on thousands of people locally.

The Vanguard was the voice of the Seattle Labor College and the Unemployed Citizens League. Click image to read more. During the early years of the Great Depression, when over 35,000 men were out of work in Seattle alone, Mark M. Litchman helped the Seattle Labor College to organize the Unemployed Citizen’s League (UCL) in 1931, and became an attorney for the League, advising its officials about their economic and legal problems.[45] The UCL tried to accommodate the basic needs of the unemployed in local communities, defend their civil rights, and to aid in their political representation.[46] Litchman helped to write drafts of relief requests from the city and county government officials on behalf of the UCL.[47] The UCL also helped to create a shared consciousness among local unemployed citizens and gave people the confidence to survive in the most devastating of times during the Great Depression.[48]

Litchman believed that by organizing people together, we could achieve social legislation that would enrich the lives of everyone. He continuously appeared before groups and town meetings, teaching people the benefits of social welfare legislation during the Depression.[49] He helped explain the New Deal, the merits of the Social Security Act, the Wage and Hour Act, the Wagner Law, the Housing Act, and the Unemployment Compensation Act in simpler terms through writings and speeches to local communities so that ordinary people could better understand what the government was trying to do to alleviate the Great Depression. Litchman also did this to further his goal of organizing people so that they could collectively demand more help from the government, which would result in the betterment of all people.[50]

As a result of his political and social beliefs, Litchman also helped to form the Washington Commonwealth Federation, a progressive-labor-radical political coalition in 1933, and the Washington Pension Union in the early 1930s, and became an attorney for them.[51] The political power that these two groups obtained helped to rewrite state laws, which gave Washington State some of the most liberal and comprehensive pension and welfare policies in the nation by the end of the Great Depression.[52] Moreover, Litchman was successful as a counsel in sustaining the constitutionality of the Washington Old Age Pension Act in McDonald v. Stevenson in 1933 that helped poor elderly people of the state who were most in need of financial stability and aid during the Great Depression. This case was also instrumental in enacting legislation that went to aiding dependent children of entitled pensioners, blind workmens’ compensation, and unemployment compensation.[53] This case was enormously helpful to those in Washington State who were experiencing the worst of the economic turmoil of the 1930s. But that same year, Litchman would take on the case of which he would become most proud, which he would later claim as being “one of the most important labor cases in history without a trial.”[54]

When Litchman spoke of his legal career, he would consistently point out the “Yakima 100” case of 1933 as one of his defining moments as a lawyer and as an advocate for civil rights. The year 1933 was an important one in the history of American labor.[55] Great increases in union membership occurred that year as more and more frustrated workers across the nation became fed up with dealing with the past three years of debilitating economic depression. As the year progressed, a new era of militant unionism arose among the nation’s industrial work forces. The IWW saw an immense opportunity to start re-organizing its ranks in the Yakima Valley of Eastern Washington, a region that attracted thousands of migrant workers each year with its plentiful work on fruit orchards and hops farms.[56] But those very conditions fueled conflict as available work became more competitive and harder to find, and the clashes between farmworkers and local police and business made it an especially hostile region to organized labor and radicals. The IWW organizers began to attract many of the non-unionized farm workers in the Yakima Valley with promises of protest and immediate action against the farm owners.[57] Low wages and long hours were the biggest complaint among the farmworkers, and the Wobblies (another term for IWW members) began organizing people into picket lines on farms all around the Yakima Valley in order to demand wage increases, shorter workdays, and a halt to child labor on the farms.[58]

The first time Litchman defended anyone in Yakima Valley was when he represented several hop workers arrested on May 17, 1933 for picketing illegally.[59] In a letter to the ACLU, Litchman described how he came to defend the hop workers protesting for a wage increase that paid more than one cent per hour:

"Nine men and women [hop workers] were arrested by the prosecuting attorney of Yakima County, Washington, charged with trespassing on the premises of a hop grower…known as Andrew Slavin, and were also charged with unlawful assembly in that they assembled for the purpose of preventing persons from entering the Slavin Farms…I was employed by the IWW organization…to defend these hop workers."[60]

Litchman was able to meet with the arrested hop workers and negotiated a deal where they would be allowed to picket the hop growers as long as no more than two workers at a time picketed along the highway at twenty-five feet apart.[61] Litchman was able to obtain this deal with the cooperation of the local prosecuting attorney, the Sheriff, and the local IWW organizing committee, while also releasing nine arrested hop workers and 18 additional picketers.[62] And although they acknowledged Litchman’s diplomatic efforts on behalf of those jailed, the Wobblies claimed a great victory in the release of its jailed members and the right to resume protests on behalf of “the solidarity of the workers using their [unions and own actions] to open the jail doors.”[63] When more than 100 picketers were arrested in the Yakima Valley after a protest in August of that same year, the IWW again enlisted the legal defense of the experienced Mark M. Litchman for the Yakima 100 case.[64]

This stockade was built built within 24 hours specifically for the prisoners of the battle at Congdon Orchards, August 10, 1939. (Courtesy Library of Congress). Click image to learn more about the strike.

The arrested defendants in the Yakima 100 case included both IWW members and non-members who participated in a picket organized by the Agricultural Workers Industrial Union No. 110 (part of the IWW’s union federation) that occurred on August 26, 1933. At 11:00 am on that day, picketers gathered on the Congdon Farm in Yakima Valley and were peacefully protesting when a group of vigilante farmers and local business men approached, armed with gas-pipes, pitchforks, clubs, and other weapons. When the picketers refused to leave, a bloody fight ensued in which the picketers were outnumbered five to one.[65] And while none of the picketers escaped without injury, just because one farmer was injured, 65 of the jailed picketers were charged with first-degree assault. The rest of the 100 jailed were charged with unlawful assembly, criminal syndicalism, or disorderly conduct.[66] What was worse, the jailed picketers were kept in “bullpens,” nothing more than poorly devised open-air metal cages where as many as 80 people were stuffed inside of at one time with inadequate medical care, food, or sleeping space.[67]

Litchman felt compelled to defend the jailed picketers after viewing their holding conditions in addition to the miserable living conditions of most unemployed in the Yakima Valley who he saw living “three to four to a room,” with some living in chicken coops and woodsheds.[68] As soon as Litchman arrived in Yakima Valley that August, he began interviewing every single one of the jailed picketers. He found that a large number of his defendants were only guilty of minor offenses, and persuaded the local prosecuting attorney, Sandvig, to release over half of the jailed defendants—particularly as it was costing the already impoverished Yakima County taxpayers thousands of dollars to keep them jailed. Although successful at this, Litchman was unable to gain the immediate release of anyone judged by Sandvig to be “hard core” members of the IWW.[69] Additionally, Litchman’s efforts to negotiate or at least talk with local farmers failed, as they continuously refused to meet with him.

Litchman’s next move was to motion for a new location for the trial in light of the intense anti-IWW feeling that existed in the Yakima Valley.[70] In a letter to the American Civil Liberties Union, Litchman assumed he had as much chance of winning a trial in Yakima County as “the proverbial snowball has in hell” because the hatred towards his clients would not permit a fair trial and jury.[71] However, the motion to move the trial was denied by presiding Judge A.W. Hawkins, and rather than settle for an unfair trial, Litchman began to devise ways to avoid having a trial altogether.[72] Some of these strategies included persuading both the prosecuting attorney and local influential people in Yakima County that the best solution would be to dismiss most, if not all, of the charges and to release the rest of the jailed defendants. He did this by emphasizing the cost of keeping them in jail and the costs of an ongoing trial, which would be an enormous burden on taxpayers.[73] Moreover, Litchman reiterated the huge public outcry that would result in a conviction of the defendants because the charges were so poorly constructed.[74]

After reading Litchman’s proposal, Sandvig submitted his own proposition to the court on the day of the scheduled trial, December 16, 1933. Sandvig’s proposition stated that the prosecution would release all of the defendants charged with first-degree assault if twelve of the jailed IWW members pleaded guilty to vagrancy and on the further condition that all of the non-resident defendants would leave Yakima and stay away for at least one year.[75] Litchman and his clients happily agreed to this proposition, as even those who pleaded to vagrancy would be released immediately as their sentence was 90 days of jail time, which began on the day they were originally arrested.[76]

Even though Litchman won this massive victory for the IWW, the defendants involved, and for the labor movement in general, Litchman received very little compensation for defending the Yakima 100. Litchman repeatedly wrote to the IWW General Secretary, Joseph Wagner, to ask for funds sufficient for his own personal expenses during the time he worked on the case. Although Wagner initially promised to send the money, Wagner later admitted that the Yakima Defense fundraiser had raised so little that he was unable to send Litchman anything at all.[77] But Litchman’s humble nature overrode any financial compensation that most lawyers would seek out for the same efforts. In a letter to his co-counsel in the case, Litchman wrote that he didn’t receive nearly enough funds to cover all of the acquired costs of the trial, but that he still felt a great privilege having defended the strikers in “one of the most influential labor cases in recent years.”[78] Furthermore, he was very proud of having been able to win release of all the workers and in helping struggle for basic civil rights in the process.[79]

Litchman went on to involve himself in many more social activist and intellectual pursuits through his writings and involvement in many local governmental committees. He served as a member and director of the Seattle Chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union because of his longtime devotion to sustaining civil liberties for all people.[80] From 1935 to 1941, Litchman served as a legal advisor to the Washington State Legislature and drafted more than one thousand bills.[81] Many of his drafted bills have become statutes in Washington State, showing that his legacy is still with us in our state laws. During that same time, Litchman also served as a member of the King County Advisory Committee on Social Security from 1937 to 1939.[82] Litchman was actually appointed to fill the State Senatorial post in the 4th District in the State of Washington, but did not run for re-election. In 1939, Litchman was appointed as a member of the King County Housing Commission, and served as its Director until he passed away in 1960.[83] This was the only political appointment in which he received no monetary compensation, but he did receive a great pleasure in the thought that he was helping his fellow man and the less fortunate.

In his final years, Litchman became a sought-after lecturer and prolific writer. He continued to give lectures and write pieces on federal and local legislations, and on legal and social philosophy.[84] And during one of the last years that Litchman served as the Director for the King Co. Housing Authority, the National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Officials chose to honor him for his long service, devotion, and loyalty as a “public spirited citizen” with little or no financial gain.[85] They touted Litchman as a truly inspirational advancer of social reform and noted that his contributions had greatly advanced the living conditions and environment for all the people of his city.[86] It is these words that sum up the achievements and philanthropic attitude towards the needy and destitute that Litchman carried with him throughout his entire life.

A lawyer who does not prioritize financial gain and national fame for their legal work is something of a rarity, and was even less common to do pro bono work on behalf of the unemployed and underrepresented without receiving compensation during the Great Depression when life was difficult for everyone. But Mark M. Litchman possessed all of these qualities in his legal and intellectual pursuits. He sacrificed the prestige of going to trial with huge cases and instead found pride in his work defending workers, the unemployed, and labor activists. Litchman even admitted that the decision to avoid long drawn-out trials led to his invisibility on the national stage.[87] But Litchman also said that had he been a regular lawyer, he would have taken cases like the Yakima 100 to trial, demanded a substantial sum of money, and would have received at the very least, national recognition even though he knew that his clients would probably be convicted and sent to jail. But Litchman felt that a lawyer’s first responsibility was to serve his clients admirably first and foremost.[88]

Litchman’s long legal career served to enact and sustain legislation both locally and nationally, including the enactment of the eight-hour workday in the Lumber Industry of the Pacific Northwest, the maintenance of the Old Age Pension Act, the abolishment of the Fellow-Servant Doctrine, and the passing of the Federal Compensation Act for longshoremen. Additionally, Litchman’s founding of and participation in many prominent social groups and committees such as the Seattle Labor College, the Unemployed Citizen’s League, the Washington Commonwealth Federation, and the King County Housing Commission continuously helped to improve the lives of the less fortunate members of society. It seems that Litchman tried to incorporate the advancement of social issues and labor movement issues into almost all aspects of his private and professional life. Throughout his life, and as was evident during the years of the Great Depression, Litchman was able to express a loyalty to the labor movement that was unsurpassed. He did this because he believed education and activism could empower the oppressed and better the lives of everyone. But the most inspirational thing about Mark M. Litchman was his extreme kindness and graciousness in serving causes that he knew would not gain him wealth of prestige, especially at a time when being involved in labor causes could be detrimental to a professional reputation. Furthermore, the humility with which Litchman appreciated being able to help the less fortunate certainly seemed to serve him well in successfully advancing and maintaining the labor and social causes that he fought so passionately for throughout his entire adult life.

Copyright (c) 2009, Kiyomi Nunez

HSTAA 353 Spring 2009

[1] Albert F. Gunns, Civil Liberties in Crisis: The Pacific Northwest, 1917-1940, (New York: Garland Pub., 1983), 99.

[3] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2.

[6] Mark M. Litchman, letter to Leon Rubenstein, April 5, 1934, Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2 Folder 17.

[7] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2, folder 2.

[8] General Writings, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 4.

[9] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2.

[10] General Writings, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 4.

[11] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2, folder 4.

[13] General Writings, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 4.

[15] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 3.

[16] General materials, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 1.

[17] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2, folder 5.

[18] Mark M. Litchman, letter to Leon Rubenstein, April 16, 1934, Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2, folder 16.

[19] General materials, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 1, folder 3.

[20] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2.

[22] General writings, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 3.

[23] Gunns, Civil Liberties, 101.

[24] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2.

[25] Gunns, Civil Liberties, 102.

[32] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2.

[33] Gunns, Civil Liberties, 104.

[34] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2.

[35] General Writings, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 5.

[37] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2.

[38] General Writings, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 6.

[40] General Writings, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 6.

[44] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2.

[45] Eulogy given at Funeral, 1960, Ibid.

[47] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2.

[48] Eigner, “Vanguard,” The Labor Press Project.

[49] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 3.

[51] Ibid., Box 4, folder 2.

[52] Eigner, “Vanguard,” The Labor Press Project.

[53] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 3.

[54] Ibid., Box 1, folder 2.

[55] Cletus E. Daniel, Labor Radicalism in Pacific Coast Agriculture, (Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, 1972), 154; and James G. Newbill Research Materials on Yakima Labor History, 1909-2001, Accession 5258-001, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 1, folder 4.

[58] IWW General Defense Committee Newspaper, Vigilante Justice – Second Act of Yakima Drama, November 1933, Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 5, folder 18.

[59] James G. Newbill, At the Point of Production: Yakima and the Wobblies, 1910-1936, ed. Joseph R. Conlin (Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1981), 174.

[60] Research notes, n.d., James G. Newbill Research Materials on Yakima Labor History, 1909-2001, Accession 5258-001, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 1, folder 11.

[63] Daniel, Labor Radicalism in Pacific Coast Agriculture,155; and James G. Newbill Research Materials on Yakima Labor History, 1909-2001, Accession 5258-001, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 1, folder 4.

[64] Newbill, At the Point of Production, 183.

[65] General writings, n.d.,Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 5, folder 18.

[68] Ibid., Box 2, folder 6.

[69] Daniel, Labor Radicalism in Pacific Coast Agriculture, 155: and James G. Newbill Research Materials on Yakima Labor History, 1909-2001, Accession 5258-001, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 1, folder 4.

[71] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 1.

[72] Research notes, n.d., James G. Newbill Research Materials on Yakima Labor History, 1909-2001, Accession 5258-001, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 1, folder 4.

[73] General writings, n.d.,Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 5.

[77] Daniel, Labor Radicalism in Pacific Coast Agriculture, (Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, 1972), 155; and James G. Newbill Research Materials on Yakima Labor History, 1909-2001, Accession 5258-001, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 1, folder 4.

[78] Mark M. Litchman, letter to Oscar Schumann, December 23, 1933, Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2 Folder 18.

[79] General writings, n.d.,Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 4.

[80] Biographical Information, n.d., Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 2.

[85] Biographical materials, 1967, Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 1.

[87] General writings, n.d.,Mark M. Litchman Papers, 1901-1965, Accession 165-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 4.