by Allison Lamb

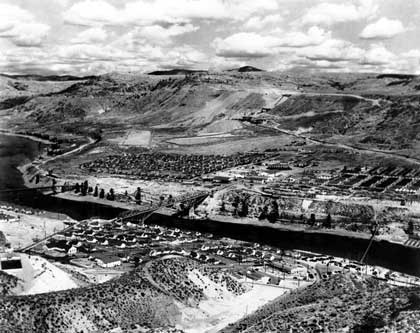

Mason City, Washington, on the shore of the Columbia River just downriver of Grand Coulee Dam, 1937. Mason City was created by the federal government and the Dam's contractor, as a planned town that would provide a high standard of living for its workforce. Mason City, on of the "towns the New Deal built," became a tourist attraction that boosters hoped emphasized the social vision of the New Deal and the ability of American technology to provide a high standard of living, beautiful homes, and recreational amenities for all Americans. Click image to enlarge. (Photo by Asahel Curtis, courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collections)

The New Deal programs of President Roosevelt’s New Deal aimed to spur economic recovery by providing federal funds for large public works projects across the nation, building infrastructure and providing jobs to the unemployed. In Washington State, the New Deal transformed the state’s landscape and public service, perhaps symbolized by the large dams like the Grand Coulee and the Bonneville Power Authority system. Public works programs, though, produced more than jobs and infrastructure: “New Deal towns” were created by public works agencies and private companies to house the many workers and families who built, maintained, and ran the dams.

Mason City, Washington was a “New Deal town” created by both public agencies and private contractor companies affiliated with the Grand Coulee Dam. The federal government needed Mason City to function as an example of what the New Deal could accomplish for both American industry, the American economy, and the lives of American workers. Private enterprise needed New Deal contracts to pull itself out of unemployment and get away from the “evil corporation” stigma that persisted. Mason City, it was hoped, would be a successful example of the government’s ability to lead people out of the recession and a display of the benefits of wide-scale social planning. The Grand Coulee Dam’s hydroelectric system would also, it was hoped, reinstate Americans’ faith in their country’s natural resources and technological prowess.[1] The Grand Coulee Dam and Mason City stood for not only the promise of hydroelectric power, but also a better living standard for the average American and the reliability of the federal government.

Communities like Mason City were originally meant to be provisional camps for workers, engineers, and contractors, but soon took on more political and substantial responsibilities. As Grand Coulee Dam’s popularity grew, more and more people migrated to the area to visit what was gaining a reputation as a symbol of a greater America. Mason City took on the overwhelming popularity and grandeur of the Grand Coulee Dam, successfully advancing both the Dam’s reputation and a successful image of New Deal public works programs. Mason City projected an image of a progressive town for American workers with a welcoming atmosphere and an aesthetically pleasing, forward-thinking planned community. Mason City’s school system, recreational programs, and modern boom-town appeal made it an attractive addition to the Grand Coulee dam’s symbolism and a model for towns across the country.[2] Though Mason City was, in reality, more an anomalous social experiment than a usable model for normal American towns, it succeeded in projecting an image of the New Deal’s social and technological success.

Early on, many New Deal towns set out to be “modern” and, according to 1934 news coverage, “of high standard.” The economic crisis had caused the growth of shantytowns and the decline of city services in many places, and New Deal towns set out to counteract that image: city planning committees all over the county forbade cesspools and shacks and mandated that all houses be substantially built and connected to sewer systems. The contractor town of the Grand Coulee Dam was to be noticeably different, a “contrast to the mushroom growth and flimsy construction of the towns that that have grown up in the area.” [3] The clean image of New Deal towns was also a reaction to the hastily built towns that American companies had provided for their workers since the 1800s: the New Deal, it was hoped, would be seen as change from the Depression era’s poverty and industrial exploitation of its workforce.[4] Though New Deal towns were run by company contractors, they were sponsored by government funds, and so both the government and the company image was at stake. Even before a contractor was selected the government specified how the town was to appear—proof that Grand Coulee boosters wanted the town to shine as an example of what a new age, public works project support town could be.

The government promised to pay for the foundation of the town, while the contractors were responsible for the town’s amenities, infrastructure, civil institutions, and appearance. Federal specifications mandated that the contractor’s camp have a “reasonable attractiveness.” Stability and permanence were important attributes as well, and buildings were required to have concrete foundations. Proper bathing facilities were essential for residential buildings, including houses and dormitories, and no more than two people could sleep in the same room. The contractor was to own everything in the town and could construct extra buildings for businesses and churches if approved by the contracting officer. Safety was also addressed: for example, the contractor was made responsible for providing adequate water pressure in case of fire. Other basic town needs like school systems and employee education were to be arranged between the contractor and the proper State and County authorities.[5] Through these requirements, the government sought to take prevent the proliferation of shack towns associated with the Great Depression. With all the amenities that so many small towns lost as a result of the Depression, the new contractor’s town would present a fresh opportunity to workers and their families as well as add to the inspiring image of the Grand Coulee Dam’s construction.

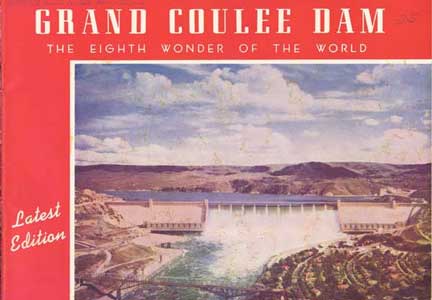

The Grand Coulee Dam was touted by regional and federal boosters as the "eighth wonder of the world," as in this promotional pamphlet, and was one of the largest manmade construction projects to be attempted. The Dam symbolized progress, technology, and a sweeping vision of remaking America, and New Dealers hoped that the Dam's image could counteract the doubt and instability wrought by the financial crisis. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Library Digital Collection.)

Mason City’s name comes from the contractor who acquired the first unit contract by the Public Works Administration (PWA) for the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam and its accompanying town. This was the Silas Mason Company of New York, also known as the Mason-Walsh-Atkinsin-Kier Company (MWAK). In a swift and surprising move, the PWA found Silas Mason’s bid of $29,339,301 acceptable and awarded the contract and start of construction immediately on July 13, 1934.[6] MWAK wasted no time preparing its “contractor’s town,” anticipating the housing of two thousand workers and residences for the support labor of cooks, clerks, and warehouse men by the year’s end.[7]

Mason City’s leaders took the town’s appearance seriously, seeking to mirror the grandeur and innovation of the Dam itself. Joseph Stansfield, a University of Washington graduate student and school system Superintendent doing research on the schools of the Grand Coulee Dam area, provides us with important descriptions of Mason City in his 1939 Master’s thesis, reporting that “much was done to make it a pleasant community, and all grounds about the residences and office buildings were landscaped and trees and shrubbery were planted in abundance.”[8] What had been a construction site was now a natural oasis and a site of residential bliss, made possible by advanced technology and adequate, large-scale planning. The residents of Mason City saw themselves as the makers of a new kind of city, boasting in their newsletter, “Mason City, the ultra-modern all electric city, is the largest city in the world for its age; what was only a land of sagebrush eight short months ago is now a thriving metropolis!”[9] This vision of civilization being worked out of the harsh wilderness was reminiscent of old expansionist narratives of moving west and the new opportunities untouched land held. With a well-built town they could be proud of, Mason City residents themselves became city boosters, reinforcing the federal government and Mason Company’s representation of the Grand Coulee Dam and its city as the new American ideal.

Not only were such facilities built almost immediately according to the government’s expectations but they were also maintained and repaired regularly. One 1938 landscaping and renovation job for the homes in Mason City went to the Civilian Conservation Corps, a federally-funded agency that provided jobs for young men to build trails and parks, furthering the emphasis on government-funded public works.[10] Local businesses also gained from Mason City, as local lumber companies were awarded contracts for building remodels and repairs.[11] The hydroelectric industry illustrated the success of federal works programs as well as its benefits to local industry.

Mason City’s leaders also sought to promote the city’s image as a social mecca by providing recreational opportunities for its residents, signifying the leisure and enjoyment of life outside of work. Only two years after the Mason Company acquired the contract, the town’s baseball team—the Mason City Beavers—were beginning to look good in warm-up practices.[12] Mason City’s basketball team, affectionately nicknamed the “Dam Site Boys,” would find their own victory as they beat out the town of Amber in the regional semi-finals tournament, as reported in the Spokane newspaper the Spokesman’s Review.[13] Boxing was also a favorite sport, and Mason’s recreational parks hosted a large selection of tournaments, including CCC boxing matches. Best of all, no admission was charged to such events.[14] So while some visitors may have had to return home to towns that lacked such facilities, free entertainment and sports gave Mason City residents and visitors a feeling of refinement and pleasure.

Intensively planned, the town’s success was seen as a reflection of the Grand Coulee itself. Mason City took on the responsibility of dealing with the many visitors and acted as a kind of public relations center. Because it was associated with the largest man-made structure of the time, the town was in the public’s eye from the start. Though residents were limited to contractors, town employees, engineers, and other workers, the mess hall opened its doors to the visiting public only fourteen months after the first contract was awarded, allowing visitors to become part of the Grand Coulee Dam’s social project, if only while they enjoyed a meal.[15] During this particular experience visitors saw the New Deal at work. They ate the same full meal that workers got three times per day and got a small taste of the how the project was benefitting the lives of the workers. It was not a manipulative, deprived, dirty work environment, but an organized, clean, and transparent one. This experience gave visitors the impression of the benevolence and social vision of both the government’s public works programs and the contractor’s beneficence: no longer, it seemed, would American workers be subject to poor dwellings, poverty, or exploitative environments. The aforementioned free sports and modestly priced tourist attractions were the forefront of Mason City’s outreach on behalf of the dam.

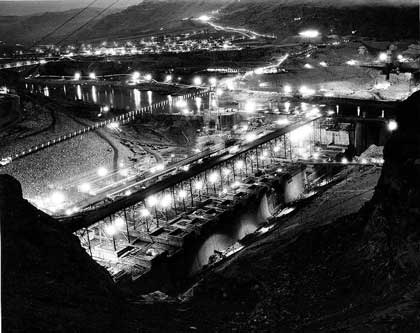

The Grand Coulee Dam construction site at night, with Mason City in the distance, 1938. The electric lights seen here symbolized the modern technology the New Deal was making available for both public works construction as well as the everyday lives of workers. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collections)

In addition to its sophisticated exterior and inviting atmosphere, the basic functions of Mason City provided its inhabitants also reflected a forward-thinking idealism. A seen in ample newsletter articles and sports sections in area newspapers, recreational facilities were ample and quite popular. By the peak of its development, Mason City had all of the basic accommodations of any well-appointed town, including a hospital, hotel, schoolhouses, two churches, a laundry, recreation buildings, office buildings, shops, warehouses, storage yards, and a mess hall.[16]

Schools played an important part in Mason City boosters’ attempts to portray the town as a “sophisticated” family town instead of being a rowdy company town of male workers. Its high school, for example, valued higher education to the point that many, including Superintendent Stansfield, thought it was too oriented toward higher education and did not include adequate vocational training. One way to track Mason City’s success in achieving the high standards its boosters claimed is to examine the city’s schools in relation to those of the neighboring city of Grand Coulee.

Mason City and its neighbor city across the Columbia River, Grand Coulee, shared the responsibility in providing all levels of schooling for the children of its two differing populations. The two communities worked together from the start fairly well, though Grand Coulee was on government land and Mason City was on the contractor’s land.[17] The two towns were in two different districts with two separate school boards. Superintendent Stansfield described the relationship as well organized, with the two boards acting as a check on one another. Because of these geographical differences, financing the schools in Mason City was different than in Grand Coulee. Instead of a school levy, residents of Mason paid higher rent and high costs of living, and the difference was attributed to community “upkeep” services like schools and fire stations.[18] Also, each district received additional regular state and county funds based on attendance.[19] By 1938 the fully accredited Mason City High School had a new building, gymnasium, and outdoor recreation fields and courts, supervised by a full-time athletics director.[20]

Mason City High School’s atmosphere and course offerings presumed that many graduates would go on to higher education, sometimes to the detriment of regular vocational training. Stansfield’s Master’s thesis remarked that the Parent Teacher Association was notably active in his survey of Mason City schools.[21] Stanfield found that two years of college or university was the median education level for parents, so it was expected that they would want the same level if not more for their own children.[22] The school’s course offerings reflected that of a prep school, emphasizing math skills and Latin proficiency. One state high school inspector visiting Mason High School found that “ample provision was made for those pupils going on to college, but little provision was made for those not going to college.”[23]

This emphasis on higher education signals a larger inconsistency between Mason City’s social ideals and the public works projects’ valuation of manpower and labor. Mason City drew a population that was disproportionately well-educated in relation to other neighboring towns. Though its own residents were highly educated, Mason high school also had to cater to the less-educated families of Grand Coulee, and which its curricula neglected. So, while Mason City was a good example of a superior town, it wasn’t a normal town with a normal population; above average is not average. Superintendent Stansfield acknowledged this discrepancy in his survey, writing:

“The very nature of the great project of the constructing of the Grand Coulee Dam affects the communities. The fact that it is the greatest engineering project ever attempted by man, that it has meant the overcoming of seemingly insuperable difficulties, that it is a constant challenge to human ingenuity and efficiency, means a distinctive type of citizenry and way of living. Unemployment in the two communities is unknown. High wages are paid and the scene is one of constant activity with the work continuing day and night.”[24]

During this time of economic depression, it was nearly unheard of for a town to have full employment or a dynamic and vibrant work atmosphere centered on cutting-edge hydroelectric technology. Superintendent Stansfield suggested in his research that Mason City should be judged as more of a social experiment or anomaly than a model for all American towns.

Though boomtowns created during the Depression, like Mason City, were not typical, they still carried great importance in promoting the competence of the New Deal and the Public Works Administration, while also demonstrating that company towns and industrial work could be pleasant for workers. New Deal towns provided support and an enjoyable, functioning community for workers and their families, doing double duty as public relations centers responsible for promoting the successful and futuristic image of public works projects. Mason City enhanced the Grand Coulee Dam’s reputation as an icon of American strength, social progress, and technology with its welcoming atmosphere, happy and educated citizenry, and visibly appealing community. Recreational programs demonstrated the value of athleticism and sportsmanship as well as the camaraderie of its residents. Finally, by opening its doors to tourism and providing ways for visitors to take part in Mason City life, the town made the experience of living in a New Deal boomtown accessible to average visitors.

New Deal boomtowns like Mason City and public works projects like Grand Coulee Dam stood for an America that had overcome the financial crisis of the Great Depression through government intervention, new socially minded business practices, modern hydroelectric technology, and large-scale social planning and public works projects. The success of these projects, however, was not limited to the images of New Deal success they produced or even the changed lives of Mason City residents. The Grand Coulee Dam provided electric power to thousands of homes in the area, beyond the reach of its support towns, and transformed the industrial capacity and geography of Washington State. President Roosevelt reflected on the greater effects of the dam, “I am very happy by the wonderful progress I have seen. We look forward not only to the great good this will do in the development of power, but also in the development of thousands of homes.”[25] Completing the dam was only possible with the help of thousands of workers, advanced technology, government planning and funding, company resources, and a supportive surrounding community, an apt metaphor for the New Deal vision of how Americans could overcome the Great Depression.

Copyright (c) 2010, Allison LambHSTAA 498 Winter 2010

[2] “Mason Camp, Operation Plant and Bridge to Be Under Way Soon.” Spokesman Review 07/14/34.

[3] “See headaches in work on dam” Spokesman Review 05/13/1934.

[4] Carlson, Linda. Company Towns in the Pacific Northwest Seattle (Wash.): University of Washington Press, 2003.

[5] “Give good care to dam workers” Spokesman Review 05/5/1934.

[6] “Mason Camp, Operation Plant and Bridge to Be Under Way Soon” Spokesman Review 07/14/34.

[7] “Mason Offices Teem with Life” Spokesman Review 06/22/1934.

[8] Stansfield, Joseph W. 1939. Parent opinion and school administration in the Coulee Dam public schools. Thesis (M.A.)--University of Washington, p. 22.

[9] The Columbian, July 1935.

[10] “CCC Gets Assignment” Spokesman Review 01/05/1938.

[11] “Local Lumber Firms Sell Dam Material” Spokesman Review, 03/30/1938.

[12] “Sports” Spokesman Review 04/04/1936.

[13] “Dam site boys nail game tight” Spokesman Review 6/24/1936; and “Mason City 33, Amber 13” Spokesman Review 02/22/1936.

[14] “Boss Ring Finals” Spokesman Review 08/30/35

[15] “MWAK Mess Hall Welcomes Public” Spokesman Review 09/18/1935

[16] “Grand Coulee Dam” pamphlet, U.S. Government Printing Office 6-9781, in the Sole Edward Hutton Papers, University of Washington Library Special Collections.

[17] Stansfield, Parent Opinion and School Administration, 23.

[18] Stansfield, Parent Opinion and School Administration, 25.

[19] Stansfield, Parent Opinion and School Administration, 24.

[20] Stansfield, Parent Opinion and School Administration, 26.

[21] Stansfield, Parent Opinion and School Administration, 26.

[22] Stansfield, Parent Opinion and School Administration, 31.

[23] Stansfield, Parent Opinion and School Administration, 63 and 69.

[24] Stansfield, Parent Opinion and School Administration, 27.

[25] “Grand Coulee Dam” pamphlet, US Govt. Printing Office.