by Katherine Samuels

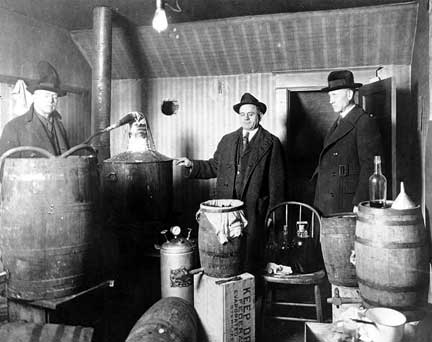

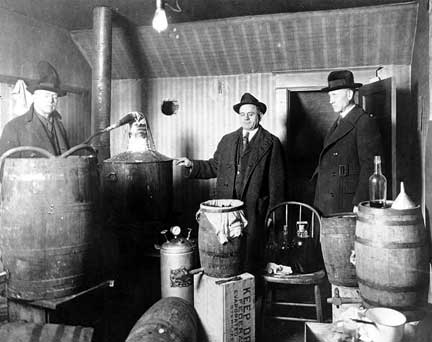

Despite the best efforts of authorities, Seattle remained "wet" during Prohibition. Here, King County Sheriff Matt Starwich destroys bottles of confiscated alcohol, ca. 1925. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Library Digital Collections.)

Seattle has had many “noble experiments” in its day: smoking prohibition that lasted from 1893 to 1911, gambling prohibition, and liquor prohibition. In Washington State, liquor prohibition began in 1916 before most other states and before the ratification of the 18th Amendment which banned liquor nationwide. Officially, prohibition ended when that amendment was repealed on December 5, 1933. Yet Seattle, perhaps best known for its rain, was wet in more ways than one by the end of the Prohibition Era.[1]

This essay examines the last years of prohibition in Seattle based partly on a survey of the Seattle Times in 1932 and 1933. It shows that Seattle’s drinking culture did not change under Prohibition. As the repeal of prohibition neared and Washington State ratified the 21st Amendment ending prohibition on October 3, 1933, the debate in Seattle shifted from whether prohibition should be repealed to debates over how much it would be taxed, referencing the inevitability of legal alcohol sales once again.

Politically Wet

Herbert Hoover was elected into the Presidency in 1928, one year before the Great Depression began. His failure to improve the economic and social crisis made him a highly unpopular president who was forced to dodge rotten vegetables thrown by the American voters.[2] Roosevelt, a Democrat, ran against Hoover in 1932 on a ticket of change—not only the New Deal, but also the repeal of prohibition. Roosevelt’s 1932 victory was a landslide nationwide, capturing all but six states on the East Coast. In Washington State, Roosevelt received 54% of the popular vote in the primary. On October 16th, the Seattle Times reported the primary results for this election (see Figure 1).[3] It is clear that King, Pierce, and Spokane counties, the most populous in Washington at well over 100,000 people, voted “wet” for Roosevelt.[4] Western Washington’s “wet tendencies,” congressman John Summers argued in October of 1932, must be countered by “build[ing] up strong organizations to oppose it in every district of Eastern Washington.”[5] Though Summers referenced this West/East divide among wets and dries, it was still true that parts of Eastern Washington had majority votes for Roosevelt, though not as high as support along the coastal Northwest: a poll reported in the Seattle Times on October 21st of 1932 shows that Yakima, in central Washington, went for Roosevelt with 58% of the vote, compared to Portland, OR where Roosevelt was thought to have 67%.[6]

These “wet tendencies” may have many different causes, but one of them was probably concern over the rise of organized crime associated with prohibition. “Wet” advocate and Times columnist Mr. Simonelli argued, “I insist and know most people will agree with me that the main reason why prohibition is going into the discard had been the fact that it was the principal source of revenue for the criminal element in this nation.”[7] Even dries agreed with this statement: “Correct you are, Mr. Simonelli,” journalist W. W. Sawyer wrote in an editorial to the Times, “but would you prefer that the criminal element should derive its revenue from kidnapping safe-cracking, hold-ups, etc., rather than from the liquor business?”[8] Not only did prohibition enable the funding of organized crime, but it also created a thriving business of rum-running and moonshine, especially in Seattle where liquor arrived on boats from Canada.[9]

Support for Roosevelt’s wet policies was also assured in Western Washington simply because prohibition had failed to change Seattle’s drinking culture, as we can see from articles in the Times during prohibition’s disintegration. The federal Cullen-Harrison Act, which became law in April of 1933, made beer with a 3.2% alcohol content legal. On Sunday October 1, 1933, the Seattle Times quoted the Farm Bureau News: “now that California, Oregon and Washington have voted for repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment this will probably be known as the Wet Coast.”[10] The next day, the Times ran an article about a foot race sponsored by a beer company in which waiters competed to see who could run fastest without spilling a glass of beer (see Figure 2).[11] On Tuesday the Times reported that a prohibition case had been dropped when the prosecuting sheriffs failed to come to court.[12] On Thursday of that week, an article about a bar in Seattle that gave away free beer for half an hour was quoted as saying “we have found this is a good way to collect at crowd. They’ll drink a lot of beer during the free half hour, but most of them will stay the rest of the evening and drink a lot more. It pays in the long run.”[13] It had not taken Seattle long to get back into pre-prohibition drinking culture.

This quick reversal of drinking habits and attitudes, along with the rise of organized crime, help to explain why Seattle did have “wet tendencies.” Prohibition had never managed to fundamentally change the drinking culture in Seattle, so the support of the wet presidential candidate, Roosevelt, was almost assured.

Resistance on the Wet Coast

However, Seattle was more than a political advocate of repealing prohibition, but also a site of alcohol smuggling, illegal production, and sale. On October 19, 1932, the Seattle Times reported that “working in shifts to lighten the labor and monotony of the task; deputies under Sherriff Claude G. Bannick today began to dump two [box]carloads of bottled liquor and alcohol into the sewer drains of the County-City Building…[the liquor] is valued at $67,000.” [14] The previous day, the Seattle Times had reported that the “4,000-gallon shipment… [was the] second big haul for the sheriff’s office in [sic] past two days.”[15]

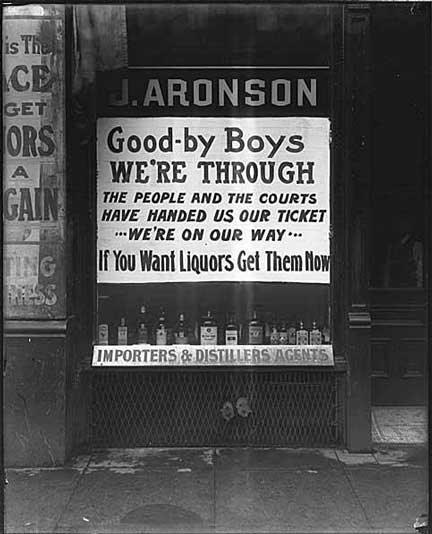

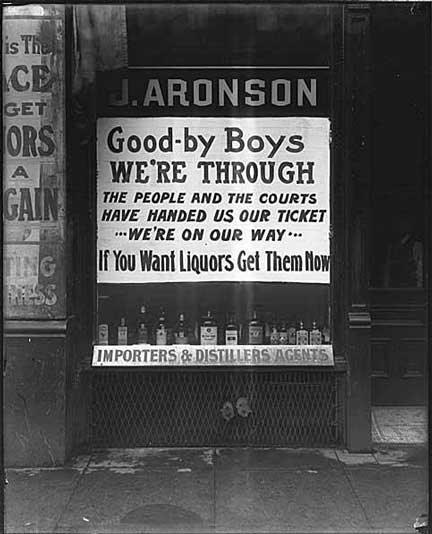

Seattle was under prohibition from 1916-1933. Here is a sign from J. Aronson Liquor store at the start of Prohibition, Seattle, ca. 1916, by Webster and Ives. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Library Digital Collections.)

In October of 1932, there were fourteen arrests or seizures of alcohol, about one every other day. Seattle was a good city for smuggling alcohol because of its wet attitude and tastes, proximity to Canada, and long coastline amenable to smuggling.[16] One of the many arrests in October of 1932 was that of Paul Walton. Walton was a 23-year-old from Blaine, Washington and was “indicted last March on a charge of smuggling 300 quarts of ale into the United States from Canada. [Walton] was arrested Saturday at Blaine.”[17] Law enforcement also seized large shipments of alcohol that passed through Seattle. One of these came from California on two boxcars, disguised as fertilizer, and was seized on October 18, 1932 in Thomas, south of Seattle. In the raid, 4,000 gallons of whiskey was seized, valued at about $32,000 (see figure 3). This was “the second big haul for sheriff’s office in past two days.”[18]

These seizures illustrate the problem that law enforcement officials had in controlling the distribution of alcohol in and around Seattle. Although many of these seizures were small—a few bottles to a few gallons—they represented the pattern of resistance to prohibition found in Seattle. This pattern of resistance also went hand-in-hand with smaller prohibition and “vice law” ordinances: Drunk driving, small alcohol seizures, and “war on vice” arrests were widespread. The “war on vice, liquor, and gambling” was declared on October 16, 1932 and resulted in 32 publicized arrests within the first week. One of the arrested, L. Young, tried to defend his arrest by bringing an expert into court to prove that pinball is a game of skill and not a game of chance, which was how gambling was defined. Unfortunately, the “expert” “didn’t get one out of ten marbles into the holes,”[19] and Young was fined $25 (see Figure 4).[20]

Alongside illegal smuggling and minor violations, large-scale illegal distilleries were found in Seattle. On October 16th, 1932, a police officer discovered an industrial distillery in the Westlake area of the city:

“Inside the plant, the officers found 5,000 gallons of sugar mash in two 2,000-gallon vats and four 250-gallon vats. They were of wood on special bases and had an elaborately designed connection with a 275-gallon still…officers also confiscated 250 gallons of “195-proof” alcohol in 50-gallon containers: 800 pounds of sugar, 200 pounds of yeast and a complete analytical chemical laboratory…the plant had been operating twenty-four hours a day since last April.”[21]

This massive operation illustrates the conflict between the culture of Seattle and the laws of the state and nation. Prohibition may have been in effect, but that did not stop professional bootlegging operations from resisting prohibition and supplying Seattle with its liquor needs, and neither did it stop ordinary Seattleites from seeking out smuggled liquor or breaking vice laws.

“Sounding the Death Knell”

On October 2nd, 1932 Dr. F. Scott McBride was optimistically quoted, “it now appears certain that the Congress to be elected this fall will not submit a resolution to modify or repeal the Eighteenth Amendment.”[22] Three months later on page four, the Seattle Times ran a headline “Church Magazine Says Prohibition is Dead as Dodo.”[23] As 1932 progressed to 1933, prohibition became an increasingly important issue. This gradual shift of public attention was apparent in the Seattle Times, as the number of editorial letters concerning prohibition rose from October 1932 to January 1933, and again until October 1933. As the number of published letters rose, the focus of the letters changed. Although as late as October of 1933 some authors still favored prohibition, the main focus was on the laws that should come into effect after the end of prohibition. The political camps shifted from wet and dry to those favoring “wetter” versus “drier” alcohol control laws.

King County Sheriff Matt Starwich (center) and two men in a room with still and bootlegging materials, ca. 1925. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Library Digital Collections.)

Taxation in moderation and a new era of drinking culture were themes represented in the ongoing debate over new alcohol laws in the Times in 1932 and 1933 “When the 18th Amendment finally checks out, other liquor laws will and must be passed and put into action; otherwise this nation will end in chaos.”[24] All of the letter writers agreed that laws were needed, but there was great discussion on what laws were needed. In his editorial titled “Without Excesses,” wet advocate Simonelli suggested a plan that reflected suggestions in other letters. Mr. Simonelli advised moderate taxation and licensing fees for alcohol coupled with the establishment of respectable drinking houses.[25] In a different editorial column written a year later, the editor quoted the Centralia Chronicle calling for “sensible laws against [alcohol] abuse” while the Bremerton News asked citizens to “render a useful public service…to find a practical method of control.”[26] Some dry advocates disagreed, but understood exactly the content of the laws wets were advocating: W.S.R. wrote to the Times in 1932, “The wets are very anxious to say that they do not want the return of the saloon…[Wets] want to bring back the worst part of the saloon (the drink) and oust the social side.”[27] Moderate taxation and moderate drinking were the main themes in the editorial letters; while the moral argument that had been used to institute Prohibition did not completely disappear, it had changed into a desire to promote respectable drinking.

The newspaper articles also followed the trends found in the editorial section. Pictures of Dry parades (see figure 5)[28] were replaced with ads for beer (see figure 6)[29] and the Times was filled with articles outlining the “beer tax” dispute. This dispute, like the editorial letters, was over the appropriate amount of taxation, not the actual act of repeal itself. “Sounding the death knell, perhaps for moderate priced beer and further development of the brewing industry…the City Council [of Seattle] has lined up for a municipal tax of $2 a barrel…to help finance the bloated city budget.”[30] Seattle City Mayor John Dore vetoed the tax, arguing that “the beer tax measure would have the effect of keeping up the retail price of beer and defeating the purposes of the average citizen who has voted for the repeal.”[31] Nine days later, the City Council unanimously overrode Dore’s veto, placing a tax of ½-cent on each glass (16oz) of beer.[32] Arthur Banon, a lawyer hired by brewing companies, complained, “there is no other place in the country where such a high tax has been proposed.”[33] Despite Seattle’s desire for repeal, it seemed that it would come at a higher cost for the average Seattle citizen.

“How Times Have Changed!”

“How times have changed! Sheriff Fremont Campbell today received a letter from a woman, asking the aid of officers in recovering the dome of a moonshine still, which she says was stolen.”[34] Much changed for Seattleites between October of 1932 and October of 1933, and the ability to ask police to locate a missing distillery piece was only one of them. Seattle saw the election of President Roosevelt, the decline of prohibition, and the legalization of beer and light wine.[35] During prohibition, wet Seattle never managed to lose the culture of drinking despite the strongest efforts of the drier counties in Washington. Seattle had smuggling, drunk driving, liquor delivery businesses, and organized crime. This drinking culture, never completely dried out by prohibition or by the ethos of the rest of the state, may have benefited Seattle’s need for social relief during the Great Depression: not only did the new $2-per-barrel tax on beer finance the city’s expenditures, but Western Washington’s “wet” climate led to support for Roosevelt and his New Deal over Hoover and his inaction around the economic crisis.[36]

Copyright (c) Katherine Samuels

HSTAA 105 Winter 2009

[1] Cassandra Tate, History Link, http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=5339.

[2] Bill Browning, How Obama Can Win Indiana, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/bil-browning/how-obama-can-win-indiana_b_118863.html.

[3] “Official State Primary Returns Comfort G.O.P.,” Seattle Times, October 16, 1932; C. Daniels, Map of Counties in Washington State, http://www.tricity.wsu.edu/~cdaniels/maps/wacountymap.htm.

[4] State of Washington, Historical Data Set: Decennial Population Counts for the State, Counties, and Cities, 1890 to 2000, http://www.ofm.wa.gov/pop/decseries/default.asp.

[5] “Summer Brands Initiative 61 Bootlegger Bill,” Seattle Times, October 21, 1932.

[6] “Yakima Poll is for Roosevelt,” Seattle Times, October 22, 1932.

[7] “Liquor and Crime” Seattle Times, October 13, 1933.

[8] “Liquor and Crime” Seattle Times, October 13, 1933.

[9] William Rorabaugh, "The Noble Experiment" (lecture, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, February 3, 2009).

[10] “Hits and Misses,” Seattle Times, October 1, 1933.

[11] “Youth Wins Waiters’ Race; No Beer Spilled in Dash,” Seattle Times, October 3, 1933.

[12] “Deputies Absent in Liquor Case, Man Saves $204,” Seattle Times, October 3, 1933.

[13] “Free Beer—Crowds,” Seattle Times, October 5, 1933.

[14] “Liquor Spilling Tedious Job for Sheriff’s Force,” Seattle Times, October 19, 1932.

[15] “3 Arrested Near Auburn as Deputies Lie in Wait,” Seattle Times, October 10, 1932.

[16] William Rorabaugh, "The Noble Experiment" (lecture, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, February 3, 2009).

[17] “Woman Recovers Beer as Evidence in Auto Crash,” Seattle Times, October 3, 1932.

[18] “3 Arrested Near Auburn as Deputies Lie in Wait,” Seattle Times, October 18, 1932.

[19] “‘Pin and Ball’ Expert Off His Game in Police Court,” Seattle Times, October 19, 1932.

[20] “‘Pin and Ball’ Expert Off His Game in Police Court,” Seattle Times, October 19, 1932.

[21] “Deputy, Buying Bricks, Detects Alcohol Plant,” Seattle Times, October 16, 1932.

[22] “From a Window at Washington,” Seattle Times, October 2, 1932.

[23] “Church Magazine Says Prohibition is Dead as Dodo,” Seattle Times, January 5, 1933.

[24] “What Next,” Seattle Times, October 3, 1933.

[25] Simonelli, “Without Excesses,” Seattle Times, October 4, 1933.

[26] “What the State Thinks,” Seattle Times, October 15 1933.

[27] W. S. R, “The Worst Part,” Seattle Times, October 6, 1932.

[28] “Dry Paraders,” Seattle Times, October 30, 1932.

[29] “Rainier Beer Ad,” Seattle Times, October 5, 1933.

[30] “Extra $2 Levy May Block Cut in Beer Prices,” Seattle Times, October 5, 1933.

[31] “Mayor Vetoes City Beer Tax as Intemperate,” Seattle Times, October 15, 1933.

[32] “Extra $2 Levy May Block Cut in Beer Prices,” Seattle Times, October 5, 1933.

[33] “$2 Beer Tax Plan of City Council is Called Mistake,” Seattle Times, October 8, 1933.

[34] “Woman Asks Law’s Help to Find Her Still,” Seattle Times, October 29, 1933.

[35] “Mayor Vetoes City Beer Tax as Intemperate,” Seattle Times, October 15, 1933.

[36] “Extra $2 Levy May Block Cut in Beer Prices,” Seattle Times, October 5, 1933.