by Brian Harris

Sports were a way for Seattleites to build community and enjoy themselves, a tradition that endured during the financial crisis of the Great Depression. Cleveland and Garfield High Schools' football game, 1937. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Library Digital Collection.)

It is no secret that in the years following the stock market crash in October of 1929 the country’s economy went into a downward spiral. Unemployment rates were at an astronomical high, farming as well as industry suffered, and the effects were felt throughout the whole country and the world. People had little or no money to spend on necessities like food and clothes, and one would think that entertainment industries like sports would see a huge decline. A study of newspaper articles from the 1932 Seattle Times Sports Section, however, shows the exact opposite. In hard times, people need an outlet, and for many people in Seattle either playing sports or watching sports became a much-needed leisure activity. Supporting local athletes, and in particular, supporting the effort to send Seattle athletes to the Olympic trials, also gave Seattleites a way to build community networks and civic pride. In addition, athletes and sports clubs used the loyal contributions of their fans to fundraise for organizations that provided unemployment and social relief. In a survey of the University of Washington athletics, the Seattle Indians baseball team of the Pacific Coast League, the city’s drive to send local athletes to the 1932 Olympic games, and amateur sports tournaments, I will show that the Depression didn’t have a grave effect on Seattle sports and as the year went on. Rather, the Seattle sports scene grew in size and scale, and contributed to the broader community in important ways.

One thing that contributed to a thriving Seattle sports scene in 1932 was the ability to play and attend sporting events outdoors; 125,000 people who attended the April 10, 1932 University of Washington crew race must have liked watching the race outside.[1] The relatively mild year-round climate allows a wider variety of sports, as opposed to the Midwest or East Coast, where six months of the year conditions outdoors are not conducive to outdoor sports. They are cheaper and easier to play then indoor sports. Proof of Seattle’s commitment to outdoor recreation can be found as early as January 3, 1932, in an article that informs readers the city would be adding many new handball courts, parks, and playgrounds, in some cases costing in excess of $5,000 each.[2] Another outdoor sport, golf, proved to be popular throughout the year. An early report in the Seattle Times indicates that two city-owned public golf courses, Jefferson Park and Jackson Park, showed an increase in profits from 1931 to 1932, and Lakewood Golf Club, a private club made up of mostly West Seattle residents, had extra money in the bank after paying all its bills.[3]

Sports teams, like the University of Washington Husky baseball team, faced setbacks because of the economic crisis of the Depression. Nonetheless, this sports page from the Seattle Times on April 26, 1932, shows how vital the Seattle sports scene was.

Sports teams, like the University of Washington Husky baseball team, faced setbacks because of the economic crisis of the Depression. Nonetheless, this sports page from the Seattle Times on April 26, 1932, shows how vital the Seattle sports scene was.

Early in the year there were many other indicators the Seattle sports scene was healthy. The Seattle Indians baseball team made an agreement to stay at their home ballpark Dugdale Park, and announced that they wouldn’t be trimming player salaries and would actively sign rookies.[4] The strength of baseball in the Puget Sound was further illustrated when an amateur baseball league called the Timber League was formed, giving residents and non-professional players more options to watch and play baseball.[5]

Not every team’s future was as certain as the Seattle Indians. The Puget Sound Hockey League was in danger of folding in February of 1932, and in far bigger news, the University of Washington indicated that their sports programs were facing financial peril, a situation that would drag on through the entire year before being positively resolved.[6] The Puget Sound Hockey League would ultimately find a way to stay in business as well. This indicated the importance of local sports, and the lengths sports organizations went to obtain funding during the Depression. It also shows the tremendous support of fans and Seattle citizens’ commitment to sports events during the period: the Hockey League was able to continue because of high fan attendance at games, and University alumni, students, and fans attended football games and donated goods and services to amateur athletes. This show of support by city residents demonstrates how sports gave the residents of the city something to rally around in a time of economic crisis.

There were many times throughout the year that the University of Washington’s Husky sports programs had to take unusual measures to continue their playing seasons. Lacking funds for transportation, room, and board the University considered canceling the remainder of the spring baseball season. Determined not to let this happen, the players made arrangements to drive themselves on their final road trip, which was no small feat in 1932. Piling into six borrowed cars, the eighteen squad members made their way across the state to Pullman, WA and Idaho. Players and coaches were hosted by local fraternities and athletic clubs, thus reducing the room and board costs.[7] The UW baseball team’s experience illustrates how sports brought people together across the state, and how games came to mean more than winning, but rather came to be a symbol of community resilience.

Central to Seattle’s athletic scene in the period were the 1932 Olympic Games. With the winter games being held in Lake Placid, NY and the summer games in Los Angeles, the US wanted a good showing. The city of Seattle did its part in helping send athletes to the games, and donated gate receipts from a track and field match between the University of Washington and the Washington Athletic Club.[8] In another show of support for Seattle-based Olympic hopefuls, the University of Washington began an alumni fundraising drive of $6,500 to send the varsity crew team to the National regatta in New York, and possibly the Olympic trials in July.[9] In a show of support, 300 workers hit the streets of Seattle seeking donations for the crew team.[10]

The Seattle community rallied around their potential Olympic athletes, fundraising to send them to the Olympic trials even in the midst of the Depression, as the Seattle Times reported here on May 30, 1932.

The featured sports headline in the May 30, 1932 Seattle Times said “Olympic Funds Promised, Junior Chamber of Commerce Backs Seattle Stars.”[11] The community leaders knew how important amateur sports were to maintaining the fabric of the community. George Clark, a former University of Washington sprinter, summed it up perfectly: “We feel that all Seattle is vitally interested. The amount of money involved is not great, but the results will be of such far reaching effect that they cannot be measured in dollars and cents.”[12] Clark knew you couldn’t put a price on sports and the effect it had on a community. Seattle residents rallied around their Olympic athletes in a way seldom seen in other cities and other times. The Washington Athletic Club was chosen as the headquarters for the fundraising drive, and by June 2nd, just two days later, the fund had already received $100 in donations, climbing by June 4th to over $300.[13]

Seattle businessmen were not the only ones involved in the Olympic fundraising. The University of Washington announced that it would hold a tag sale, with the proceeds going to the Olympic efforts.[14] Not only were students able to part with older goods they did not need, but they could donate these items to the cause of civic and University pride. As these newspaper articles show, it was important for the city to send athletes to the games, for in a time of social and economic crisis, the collective effort of sending Seattle athletes to the Olympics represented a community-building achievement.

In addition to providing much-needed entertainment, Seattle sports also contributed to charities. In an article published in the Seattle Times on April 3, 1932, readers were informed there would be an exhibition charity game between the University of Washington baseball team and a team of Husky alumni. One of the members of the alumni team would be Governor Roland Hartley. The proceeds were to go to the Mayors Unemployment Fund, one of the first funds in the country set up to assist the city’s less fortunate.[15] It was events like this, bringing entertainment and philanthropy together, that kept the sports scene flourishing during the Great Depression. Much the way people gather at churches and temples, the people of Seattle gathered at the playgrounds and ballparks to show their civic pride and communal spirit.

Despite the powerful place of sports in community life, and the philanthropic gestures of sports teams, it was also a very hard financial climate in which to keep sports leagues and programs afloat. The University of Washington had to take several steps throughout the year to remain financially stable. On April 15, the school announced that it would be reducing the price of football tickets by twenty-three percent, from $3.00 to $2.50. This cut would allow more people to attend the games, and allow the school to collect more concession revenue in return.[16]

Other cities and sports leagues weren’t faring as well. Several minor league baseball associations, including leagues in Illinois, South Carolina, and Mississippi, were going under due to lack of fan attendance.[17] One that went under was the Arizona-Texas League, a minor-league team for the Pacific Coast League, who trained younger players for higher-level competition.[18] On July 25, 1932, Pacific Coast League president H.L. Baggerly paid a visit to Seattle. The purpose of his visit was to assure the Seattle ballclub and their fans that the league was healthy and in no danger of folding. Baggerly reassured Seattleites that “San Francisco isn’t drawing as it should, and possibly the rest of the circuit is a bit behind average figures, but the league as a whole is in a healthy condition.”[19] While other leagues were folding, the Pacific Coast League and the Seattle Indians were managing better than most, largely due to the loyalty of their fans and commitment of the city to sports.

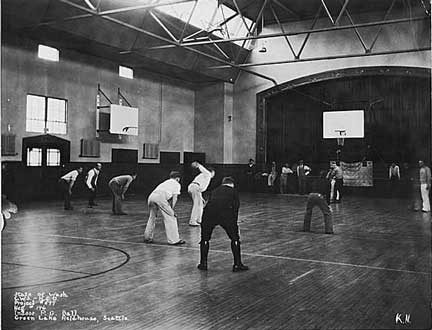

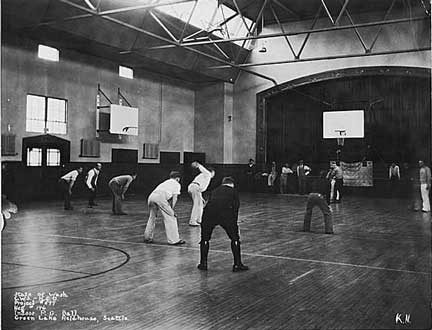

Ball game in the Green Lake Field House gym, Green Lake neighborhood, Seattle, 1933 or 1934. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Library Digital Collections.)

However, even the Seattle Indians were not free of financial problems. In the late night hours of July 4, 1932, a tragedy struck that would have put many baseball teams out of business. The Indians’s home stadium, Dugdale Park, burned to the ground, ostensibly from the careless use of fireworks. The loss of the park was devastating to the man it was named after, Daniel Edward Dugdale, who said, “It was a good park, the best on the coast when I dedicated it back in 1913.”[20] Seattle’s baseball team found itself in the same position as many of the city’s residents: homeless.

Considering the state of the economy in 1932, many clubs would have just folded, and indeed, many did for far smaller financial worries than that. In a move that proved how solid the Seattle club was, they began immediate negotiations with Civic Field to finish the season there. The club was doing so well that if they were not able to make a deal with Civic field, they were being courted by Oakland, San Diego, and Fresno.[21]

Night baseball was a necessity during these times, since during the day people would either be working or looking for work, and couldn’t afford to take the day off to enjoy a ballgame. The biggest stumbling block to the stadium question was who would pay to light Civic Field for night games. On July 8, the club jumped this hurdle when it was announced that the city had agreed to pay $3,000 to install the lights in return for eleven percent of the gate receipts.[22] This agreement not only shows how important the game of baseball and the team were, but how the sports team would materially benefit the city. On July 9th the deal was finalized. The city would make about $6,000 in revenue, money that would go into the street railway system.[23] The first game at the new ballpark, a night game on July 19th with Washington Governor Roland H. Hartley and Seattle Mayor John Dore on hand, drew 4,000 fans and saw the Indians win 11-10.[24] For everyone but the losing team, it was a win-win situation.

Chinese American basketball team, 1938. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Library Digital Collection.)

Other area sports were also faring well. Attendance for an August 29th welterweight boxing match between Tacoma native and champ Freddy Steele and Billy Townsend drew 9,000 fans to see their hometown hero successfully defend his crown. Half the proceeds from the fight went to the Mayors Unemployment Fund, totaling $5,800 for the unemployed once the gate receipts were counted.[25] Before the ink was even dry on the August 27th edition of the Seattle Times proclaiming Steele winner, the “Tacoma Wonder Boy,” was getting numerous offers for more bouts in Seattle.[26] Freddy Steele’s tournaments are further evidence of both Seattle citizens’ support for athletes and the way that the sports world contributed to the broader Seattle community.

While the city of Seattle struggled along with the rest of the country, sports gave citizens a way to build community and civic pride, while athletes used fans’ enthusiasm to help contribute to the city’s broader economic and social needs. From rallying together to send their athletes to the Olympic Games to supporting the Seattle Indians after their stadium burned down, the residents of Seattle found a way to persevere through hard times. Whether it was a sport that helped charities like the Mayors Unemployment Fund or collegiate sports like University crew or baseball that gave the residents of the city a common interest, local sports thrived during the Depression.

Copyright (c) 2009, Brian Harris

HSTAA 105 Winter 2009

[1] Alex Shults, Seattle Times (11 Apr. 1932): 15.

[2] Henry MacLeod, Seattle Times (3 Jan. 1932): 24.

[3] John Dreher, Seattle Times (10 Jan. 1932): 20.

[4] Seattle Times (5 Jan. 1932):16.

[5] Seattle Times (29 Mar. 1932):18.

[6] Ed Peltret, Seattle Times (21 Feb. 1932): 16.

[7] George Varnell, Seattle Times (28 Apr. 1932): 23.

[8] George Varnell, Seattle Times (15 Mar. 1932): 17.

[9] George Varnell, Seattle Times (17 Apr. 1932): 23.

[10] George Varnell, Seattle Times (21 Apr. 1932): 18.

[11] George Varnell, Seattle Times (30 May 1932): 12.

[12] George Varnell, Seattle Times (30 May 1932): 12.

[13] Seattle Times (4 Jun. 1932): 7.

[14] Seattle Times (5 Jun. 1932): 27.

[15] Seattle Times, (3 April, 1932).

[16] George Varnell, Seattle Times (15 Apr. 1932): 17.

[17] William Weeks, Seattle Times (13 Jul. 1932): 16.

[18] Alex Shults, Seattle Times (26 Jul 1932): 14.

[19] Baggerly quoted in Alex Shults, Seattle Times (26 Jul 1932): 14.

[20] Alex Shults, Seattle Times (5 Jul 1932): 16.

[21] Seattle Times (6 Jul. 1932): 18.

[22] Seattle Times (8 Jul. 1932): 21.

[23] Ken Binns, The Seattle Times (9 Jul 1932): 7.

[24] Alex Shults, Seattle Times (20 Jul 1932): 10.

[25] Alex Shults, Seattle Times (27 Aug 1932): 7.

[26] Seattle Times (27 Aug 1932): 18.