by Kristin Ebeling

Timber crew from the Clemons Logging Company, on the Chehalis River east of Aberdeen. By 1935, Washington's timber workers went on strike for better conditions and the legal recognition of their union. The timber workers' strike faced an often unsympathetic or hostile media reception and began printing their own newspaper to counteract mainstream media bias. Click photo to enlarge. (Photo courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collections)

By the turn of the twentieth century, lumber was one of the major industries in Washington State. The Northern Pacific Railroad had finally reached cities in the Northwest by the late 1800s, which opened up the largely untapped timber resources to the rest of the world. Portland, Tacoma, and Seattle, along with surrounding cities, economically benefitted from the booming logging and timber refining industries, enabled by their new connection to the rest of the country.[1] As logging took off in the outskirts of town, urban-dwelling men took jobs in the new mills, refining the fresh timber into beams, boxes, and the like, which were then shipped out to other manufactures around the globe.

By 1935 the men of the timber industry were fed-up with their meager wages, conditions, and lack of job security for what was a physically strenuous and often dangerous occupation. Further, the industry was thriving and the majority of workers felt they deserved more of the wealth they were helping to create. Timber workers in 1917 had gone on strike successfully for similar reasons, buoyed by a larger wave of worker radicalism in the Northwest, yet without legal legitimacy, unionism in the lumber industry had failed to become securely established or organized.

By the mid-1930s there was a renewed vigor for labor organizing in America resulting from the union busting of the 1920s followed by the heartbreak and outrage of the Great Depression. By the end of the 1935 timber strike, unlike in the early 1900s, federal legislation provided the legal footing and necessary for the creation of strong unions. The National Labor Relations Act, a part of Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation signed into law on July 5, 1935 gave workers the right to join and create unions without discrimination, to collectively bargain with their employers, to strike legally, and more.[2] The timber workingmen of the Northwest seized on this promise and fought to make it a reality, inspired by the new legislation, pushed by their working conditions, and empowered by their extreme bargaining power as laborers in the premiere economic industry of the Northwest. Indeed, timber workers could easily strangle the Northwest’s economy, shutting down timber and its countless dependent enterprises with one word— “strike.”

Print media, which depends very heavily on wood products, followed the timber worker strike of 1935 very closely. With almost daily coverage, the articles covering strike developments took on a certain tone depending on what was being reported. During the timber strike of 1935, as the strike progressed from early April to the end of June, The Seattle Star shifted its coverage to be less and less in support of the strike, as the events became more controversial and threatening to businesses and the local government. The lack of sympathy in The Stars’ reporting of the 1935 strike proved the necessity for a union-created, pro-strike press, and The Timber Worker of Aberdeen, Washington, was born out of this need.[3]

The movement for better wages and working conditions in the timber industry had been sparked by the successful coast-wide strike of longshoremen in 1934. Many American Federation of Labor (A.F.L.) affiliated timber locals had assisted the dockworkers during their successful struggle and soon decided that it was their time to shine. In late March of 1935, the Northwest Council of Sawmill and Timber Workers’ Unions gathered in Aberdeen, Washington. This council then voted to become part of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America, A.F.L., with A.W. Muir as their leader. They agreed to strike on May 6th if employers did not meet their demands.[4]

By late April, The Seattle Star began covering the labor dispute in the timber world. On April 29th, an article announced that the newly elected Muir believed an agreement could be made, which would avert the threatened strike. The article mentioned the millmen’s demands as being a wage increase to $.75/hour and a 30-hour workweek,[5] but in fact the March convention also called for overtime and holiday pay, a seniority system, and most importantly, union recognition.[6] A few days later, The Star reported that the newly formed International Longshoremen’s Association (I.L.A.), a union who won recognition out of the 1934 dockworkers’ strike, would refuse to handle any lumber from non-union mills and that walkouts in Olympia and other areas had already begun.[7] At this point, the news coverage was reasonably neutral in tone. Yet, the strike, which would soon stall the Northwest economy in the coming months, had yet to make front-page headlines.

An article in the May 8, 1935 issue of The Seattle Star about the spread of the timber workers' strike through Washington State.

Once the strike was called, The Seattle Star’s journalistic coverage clearly favored business interests over the striking workers, though the paper did give more information about the millmen’s demands. On May 6th, The Star announced: “Strike Shuts Down Lumber Camps Today—Whole Industry Bows to Labor Trouble—First Since the War.” The article continued by stating that only three mills in Seattle were running, with twelve shut down in Tacoma, and none running in Portland. The article also included more of the workers’ demands, such as having a “closed shop”—where only union members could be hired—and paid vacation, as well as describing how the men were currently making 42½ cents/hour, which had been left out in previous articles.[8]

Although this column provided more information on why these men were striking, the overt bias can be seen by the description of their actions as “trouble.” This language downplayed the laborers as childish, when in reality they were fighting for legitimate goals in order to improve their standard of living. The very next day, headlines read: “City Little Affected by Mill Strike” and continued, “16,000 Timber Workers made Jobless by Northwest Lumber Walkout.” These two highly paradoxical statements induced confusion, for it is impossible that a city could be hardly affected by thousands of workers walking out of an important state industry. Also, the assertion that workers were “made jobless” is misleading, as the majority of mill workers, those who decided to strike, clearly did so because they themselves chose to. Further, the article asserted that Communists were behind the strike as well as the new leader of the I.L.A., Harry Bridges (who was indeed a member of the Communist Party).[9]

The next consecutive articles published also took a business-oriented stance. Following on May 8th, The Star reported that all but five companies north of the Columbia River were in operation, and six sawmills had been “hit” in Seattle.[10] By May 11th, $2,000,000 per week in profit losses was calculated by mill owners, compounded by lumber orders halting completely.[11] Within a few days, a compromise agreement had gone out to vote in Longview, Washington, and was rejected resolutely by the local laborers.[12] These two events proved that this strike would not be as quick and easy as initially reported by The Star, and neither were the workers simply childish troublemakers, but rather determined workers.

By the end of the month, The Seattle Star’s spin against the striking workers escalated as law enforcement became more involved and inter-union disputes occurred. May 24th marked the day Seattle Mayor Charles L. Smith declared that non-union workers, brought in by employers to keep the mills running, “will be protected from any lawlessness in which [striking millmen’s] pickets may engage” to police chief W.B. Kirtley, a declaration trumpeted by The Star. The same article also describes how A.W. Muir was becoming less favored by many rank-and-file workers because of his role as middleman between the employers and the union. Norman Lange, president of Tacoma’s Sawmill and Timber Workers’ Union, was reported to have called Muir a “Sell-out” as Muir retaliated by “firing” Lange.[13]

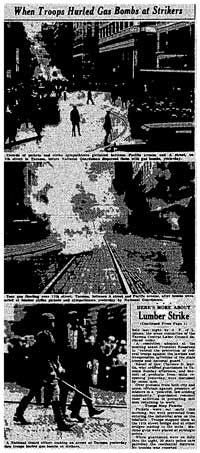

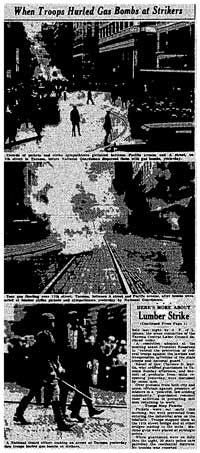

Pictures in The Seattle Star of the gas bombing of striking timber workers' pickets in Tacoma. Click image to enlarge.

On May 30th, The Star proclaimed, “Lumber Unions Vote to Go Back to Jobs” as 1,000 men at the Longview plants approved to go back to work with a $.50/hour wage.[14] The report of “unions” is deceptive because the article only mentions one local returning to work. By the beginning of June, the paper announced: “Lumber Mills Reopening in Northwest.” However, within the article it stated that only “some plants here resume operations” and no general agreement had been made with the operators and workers to end the dispute. Again, the headlines were a poor representation of actual events in this struggle. The piece continued to describe the non-union men, or scabs, taking the positions of the striking workers as they “one by one, replaced men at their old jobs,” giving the impression that the strike was concluded. Yet the actual events The Star had to report on proved their bias, and proved that the strike was far from over. Mentioned in the same article quoted above was that Grays Harbor, Portland, Aberdeen, and Bellingham mills all remained closed,[15] and two days later, The Star indeed was forced to print that the “Seattle Mills Remain Closed.”

At this time, Muir was also claiming that “radical elements” were attempting to bring down the International Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, as the Aberdeen, Olympia, and Shelton locals had all rejected him as their representative. Longview was back on strike, and The Star declared that the “Northwest lumber strike was put back into where it was two weeks ago today.”[16] On the one month anniversary of the strike, absolutely no Seattle mills were in operation, as more locals of the Northwest were abandoning Muir each day.[17] On June 7th, The Star reported on the continued closure of mills entirely from the perspective of Walter Nettleton, owner of his own lumber business. Nettleton stated his belief that unions were not necessary and that they were only being recognized because of failures in federal Depression relief policy.[18] This article, and Nettleton’s quotes, can be read as a response to the strike movement gaining power.

The Timber Worker newspaper was developed by workers in Aberdeen, Washington in the midst of the 1935 strike. It served as a voice for timberworkers and sought to counteract the negative bias of Seattle's established media.

Two weeks from this point, as the state began to assist the mill operators in re-opening the plants, The Star again took an anti-labor stance. On June 19th, the paper reported, “Several Mills Re-open Today—State patrol Protects Men in Olympia Today.”[19] The article reported that “several hundred men” were being re-employed, but neglected to clarify who these men were. Judging by the previous article describing scabs taking jobs in the mills, it is obvious that the union men were not the ones being “protected,” since no agreement had been made by this point in time: it is clear that the paper valued the protection of the scabs more than explaining the protections the union men were striking for.

“State Troopers Gas Tacoma Mill Pickets—300 National Guardsmen on Duty in City” read headlines on June 24th. This article described the spraying of tear gas on peaceful picketers in downtown Tacoma, allowing seven mills to reopen in the downtown area. According to The Star, “Little violence [was] reported,”[20] completely ignoring the violence of the tear gas used against nonviolent picketers, a substance that can cause long-term eye and breathing problems.[21] This piece continues by claiming the National Guard was sent in to “protect workers in lumber mills and factories,” although it is evident that they were defending the business owners and scab laborers, not the union men. The paper further reported approvingly that all pickets bigger than three persons were outlawed, and that a form of martial law was in effect for the city of Tacoma,[22] without noting that this was a complete obstruction of the first amendment to the U.S. constitution, not to mention the NLRA legislation given unions legal grounding. The next day, it was reported that strikers had completely retreated after 300 more National Guardsmen were brought into the city, arresting four more “troublemakers,” bringing the total arrests to twenty-one for Tacoma alone[23] and violently forcing an end to the Tacoma showdown. The final stand-off, the climax of the 1935 strike, also happened to be the apogee of The Star’s biased coverage.

The mill operators, with help from the state police and guardsmen, had brought the strike to an end shortly after the egregious gassing of protestors. By mid-July many union locals, clearly intimidated by the repression in Tacoma, sat down individually with plant owners to work out various agreements. In the majority of cases, men came back to work with higher wages, better conditions, and/or union recognition. However, violent outbreaks were still being reported as the men disagreed on the direction of the union. This breach in worker solidarity, which had surfaced during the strike, ultimately pushed the timber workers away from the A.F.L. and into the newly forming Congress of Industrial Organizations (C.I.O.), which sought to organize all workers in one industry, regardless of race, as opposed to the A.F.L.’s craft unionism, which restricted itself to skilled and mostly white workers. As the union men were radicalizing and seeing the limitations of conservative craft unionism, they also saw the need for their own labor-centered news sources that were a reflection of how they saw the world. The Seattle Star, as demonstrated here in their coverage of the 1935 timber strike, did not represent workers’ struggle or ideals. In response, workers founded their own newspaper, The Timber Worker, and printed countless other union-related and radical newsletters that could function as a voice for labor and their growing demands.

Copyright (c) 2010, Kristin Ebeling

HSTAA 105 Winter 2010

[1] Jensen, Vernon H. Lumber and Labor. New York: J.J. Little and Ives Company, 1945.

[2] Gregory, James. "Welcome to 1932" lecture. The Peoples of the United States. UW. 2 February 2010.

[3] Carroll, Gerardine, and Michael Moe. "Timber Worker." The Labor Press Project. The Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies at University of Washington, 2001 Web. 15 Feb. 2010. <http://depts.washington.edu/labhist/laborpress/TimberWorker.htm>.

[4] Jensen, Vernon H. Lumber and Labor. New York: J.J. Little and Ives Company, 1945.

[5] "Mill Strike Not Expected." The Seattle Star 29 Apr. 1935: 3. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[6] Jensen, Vernon H. Lumber and Labor. New York: J.J. Little and Ives Company, 1945.

[7] "Longshoremen May Aid Strike." The Seattle Star 4 May 1935: 2. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[8] "Strike Shuts Down Lumber Camps Today." The Seattle Star 6 May 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[9] "City Little Affected by Mill Strike." The Seattle Star 7 May 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[10] "Six Seattle Sawmills Are Hit By Strike." The Seattle Star 8 May 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[11] "Mill Men Vote On Peace Plan." The Seattle Star 11 May 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[12] "Blockade on Lumber Seen." The Seattle Star 13 May 1935: 5. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[13] "Workers Will Be Protected." The Seattle Star 24 May 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[14] "May End Strike." The Seattle Star 30 May 1935: 3. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[15] "Lumber Mills Reopening in Northwest." The Seattle Star 3 June 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[16] "Seattle Mills Remain Closed." The Seattle Star 5 June 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[17] "Lumber Strike is Stalemated." The Seattle Star 6 June 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[18] "Continuance of Strike is Seen." The Seattle Star 7 June 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[19] "Several Mills Re-open Today." The Seattle Star 19 June 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[20] "State Troopers Gas Tacoma Mill Pickets." The Seattle Star 24 June 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[21] "Tear Gas/Riot Control Agents :Public Health Emergency Preparedness : New York City AWARE : NYC DOHMH." Web. 11 Feb. 2010. <http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/bt/bt_fact_tear.shtml>.

[22] "State Troopers Gas Tacoma Mill Pickets." The Seattle Star 24 June 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.

[23] “Tacoma Strikers Retreat Under Gas Bomb Barrage.” The Seattle Star 25 June 1935: 1. Microform. Seattle Star A2202.