by Chris Kwon

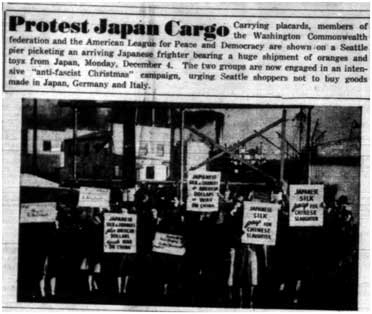

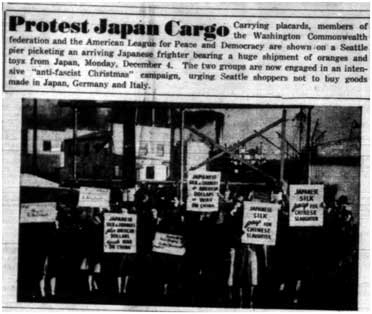

The front page of the Sunday News, the Washington Commonwealth Federation's newspaper, called for a boycott of Japanese goods in protest ofthe Japanese empire's attacks on China, and was influenced by the Communist Party's anti-fascist political orientation in 1938. The Sunday News called it here an "anti-fascist Christmas campaign," urging boycotts on Japan, Germany, and Italy. This photograph is from December 17, 1938.

There are many different forms of activism. In its simplest form, activism is an intentional act to bring about social change. Protests, marches, strikes, and boycotts have all been proven as effective ways to create social awareness and bring about social change. On the brink of war in the 1930s and 1940s, many different political groups organized boycotts of countries they saw as overly aggressive in an attempt to delay a war. The most notable expression of activism in the Seattle area and the West Coast was the Japanese boycott of 1937–1938 led by the Washington Commonwealth Federation, a left-leaning coalition of Communists and radicals that worked inside the Democratic Party. Fueled by the Japanese empire’s attack on the Republic of China, the Washington Commonwealth Federation (WCF) began boycotting Japanese goods in attempt to slow Japanese aggression toward China, which the WCF saw as a defenseless victim of attack. However, the WCF’s extensive boycott campaign ultimately hurt local business and led to increased discrimination against Japanese Americans in Washington, culminating in WCF support for Japanese American internment during World War II.

The Washington Commonwealth Federation was founded on October 5, 1935. The WCF was a left-wing alliance of trade unionists, reformers, liberals, and Communists who acted as a left bloc inside the state Democratic Party, and pushed for New Deal reforms. The WCF worked to advance progressive social and political policies and also promoted their own candidates for public office. The Communist Party played a dominant role in forming the WCF and its policies: for example, the co-founder of the WCF, Howard Costigan, was a member of the Communist Party until the Soviet Union’s signing of the non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany. Communist Party members hoped that by building an alliance with other progressive groups and working inside the Democratic Party that they could win greater social reforms and also inspire a larger mass radical movement in the United States. The WCF proved to be very influential throughout Washington and was very successful in organizing strikes, rallies, conferences, and protests throughout its short history.

The WCF was very influential among many of Seattle’s working men and women. They published a weekly newspaper, The Sunday News, and used it to bring awareness of local northwest labor activities. The first mention of a Japanese boycott appeared in the July 24, 1937 issue of The Sunday News. The main headline was “WCF ASK U.S. TO BAN JAPAN SHIPMENTS.”[1] There was no further mention of the ban or boycott in that week’s issue. Two weeks later, on August 8, the bottom column had an article urging a boycott on Japanese-made goods.[2] The article focused more on the WCF’s wish for President Franklin Roosevelt to appoint Washington Senator Schwellenbach to the vacant position on the Supreme Court. But the article did mention the WCF board’s desire to boycott Japanese-made goods and hold Japan responsible to the Nine-Power Pact, a treaty stating that the signees must “respect the territorial integrity and sovereignty of China.”[3] This was the beginning stage of the WCF’s attempts to boycott Japanese goods, and as historian Alfred Acena noted, “from November 6, 1937 onwards, The Sunday News used “BOYCOTT JAPANESE GOODS” as a column break between stories.”[4] It is noticeable that in this stage of the boycott, the WCF asked the government and officials to back a boycott of Japan. The intent of the stories and articles at this moment are more information-based, as opposed to the protest-based slant of future issues. Throughout The Sunday News, there were often updates on the events in China and Japan, and most are very biased their portrayals of the Japanese and Chinese.

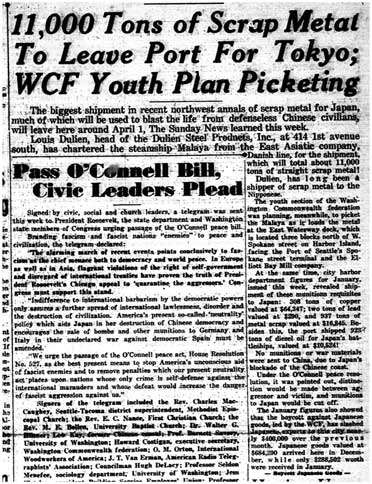

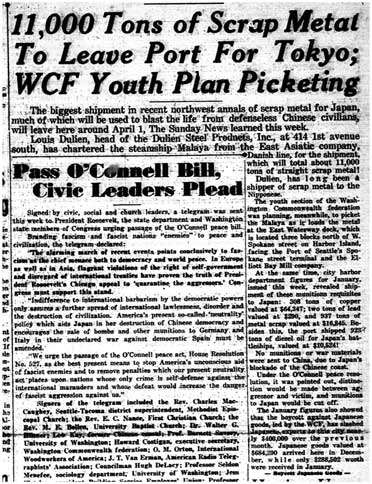

A headline from the March 26, 1938 issue of the Sunday News, announcing a picket of scrap metal shipments to Japan.

In the next week’s issue, the cover page had a small article stating that the US has been supplying Japan with military materials.[5] A figure of $200,000 was given as the amount of war materials sent to Japan by the US in the month of July alone. The article also noted that much of the cargo was shipped from Seattle, one of the main ports on the West Coast. No mention of the boycott is seen in this article, and this is another example of an informative news story about Japanese militarism. However, the position of The Sunday News was revealed more and more every week. In the August 21 issue, the pros and cons of the Nine-Power Treaty and the Neutrality Act are discussed, a debate for that was engaging the US government. The Sunday News article claims that the Neutrality Act would hurt China by placing an embargo upon it as well as Japan, while the Nine-Power Treaty would “stop the flow of all signatories’ arms, supplies and loans to the aggressor nation.”[6] It is apparent that the WCF does not seek neutrality from the ongoing war in China and Japan, but seeks to align American interests with China’s. The WCF was more of a political organization rooted around labor unions and practices than anything else. But they showed a very strong position on Japan’s “unjustified” attacks on China. Throughout the next two months, The Sunday News continued to discuss the importance of the Nine-Power Treaty and bring up the urgent action to stop shipping war goods to Japan, while taking on a more insistent opposition to Japan’s militarism.

As the Christmas season of 1937 approached, The Sunday News began to focus their boycott on consumer goods. The articles that they wrote were now directed toward the local consumer, urging them to boycott local goods. An article in the October 30 issue interviewed nine different men and women, asking them if they favored boycotting merchandise manufactured in Japan. Most replied that the boycott was necessary to cut economic stability in Japan, thus ending the war more quickly.[7] This is an interesting move in The Sunday News’s promotion of the boycott, for they have included the common Seattleite in the boycott cause and published their opinion. The paper promoted a majority consensus that the boycott was a necessary means to end the war, garnering public opinion in hopes of creating a buzz and a coalition of consumer boycotters. The Sunday News also began to publish stories on events and relief groups to China at this time, with the intention to supply China with relief from Seattle and to peacefully bring awareness to the effects of Japanese militarism on China.[8]

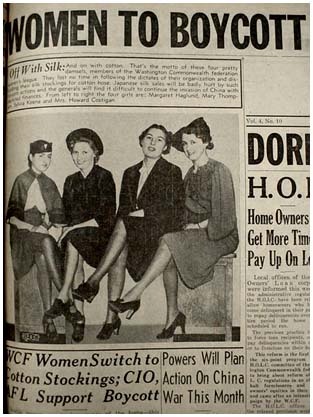

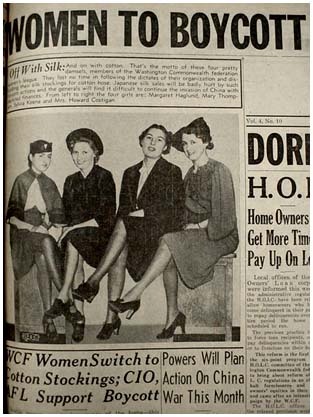

"Four pretty damsels" lead the boycott of Japanese silk stockings in this front page cheesecake story from the WCF's Sunday News October 16, 1937The biggest Japanese product the boycott targeted was silk. The WCF and The Sunday News headlined the October 16 issue with “WOMEN TO BOYCOTT JAPANESE SILK GOODS.” This pushed the boycott of Japanese silk stockings and clothing and promoted silk alternatives like cotton or raylon. At the top of the article was a picture of four smiling women showing their non-silk stockings. Statistics were also given of the amount of Japanese silk exports in the US market and how much Japanese silk was sold in the US.[9] In addition, The Sunday News claimed that Japan had admitted feeling the effects of the boycott, noting an “overproduction of Japanese textiles and drops in foreign purchases.”[10]

Beginning in November 1937, The Sunday News listed stores in the Seattle area that sold Japanese goods. The paper informed readers of all potential Japanese-made items, including imitation leather goods, brushes and combs, pearls, novelty mirrors, rag rugs, bamboo, brooms, and more.[11] The article encouraged buyers to question the origin of certain goods that may be unlabeled. This was the most direct push for a boycott by the WCF and The Sunday News, advocating the protest tactic to the general public, in hopes that a decrease in purchases would lead to more economic troubles for Japan. In addition to the boycott, the WCF youth section informed its readers that they planned to begin picketing area department stores that continued to sell Japanese-made goods. The article stated that the WCF youth’s intention was to “keep picketing every Saturday until the stores discontinue carrying Japanese merchandise.”[12]

In December, The Sunday News began urging labor bodies to create their own boycott committees in hopes of continuing the boycott of Japanese goods and hurting the economic system that fueled the war.[13] The article mentions the effects of the boycott on the Japanese economy, noting that Japanese exports have dropped by 14% because of low demand from the boycott movement.

The WCF and The Sunday News were very effective in boycotting Japanese goods. Beginning with large shipments of materials from Japan, the WCF narrowed their boycott down to everyday household items, allowing normal citizens to participate in the “fight” against Japanese militarism. This tactic led to poor sales figures for Japanese products during the Christmas season of 1937.[14] The WCF used many effective activist tools to send a message to consumers that Japanese-goods were directly fueling the war. The boycott of silk was the easiest and most direct form of boycott. Unlike other products, almost all silk in the US came from Japan, which meant that if enough people in the country were to boycott silk, the effect on Japan would be immediate. From informative articles that positioned themselves as anti-Japanese to full editorials and assessments of Japanese aggression, the WCF was able to affect local businesses with their boycott.

Grassroots methods were used from picketing, buttons, to fashion shows and relief funds, particularly by the youth section of the WCF. These young individuals came up with different methods of conducting a wider and more extensive campaign to boycott Japanese goods. This included things like picket lines, leaflets and buttons, pledge cards, speakers/lecturers to unions and Workers’ Alliances, mass meetings, demonstrations in front of the Japanese Consul’s office, popular slogans, parades, and more.[15] The WCF’s speeches and writings were also used to argue for the importance of individual commitments to boycott the Japanese. Speakers urged American buyers to take action and paralyze the Japanese war funding.[16]

In addition to their articles in The Sunday News, the Washington Commonwealth Federation wrote many letters to different labor unions, churches, and businesses urging them to create boycott committees and contribute to the boycott of Japanese goods. The American League Against War and Fascism wrote an open letter informing people of the progress of the boycott and asking them to display posters advocating the boycott.[17] Another letter written by Howard Costigan explained the effects of not boycotting Japanese goods, and urged a nation-wide boycott on Japanese goods and products to prevent unconsciously aiding the Japanese. Costigan continued by stating that Henry Ford of Ford Motor Company had been purchasing war bonds from Japan to help the invasion of China. Costigan argued for expanding the protest to include American companies who were complicit with the Japanese, and asked that “no more Ford vehicles are purchased until Ford can deny the reports.”[18]

Costigan’s letter highlights the single-minded insistence of the WCF on the boycott campaign, even at the expense of local business and American jobs, for he suggested putting thousands of innocent, working-class jobs at risk because of the Henry Ford’s funding of Japan. It is interesting to see how little the WCF cared about local businesses, being an organization that fought for labor rights so diligently. The WCF’s boycott campaign became so heated that working-class citizens of Seattle who sold Japanese goods were now being reprimanded for selling products that they had purchased before the war.

The WCF effectively hit all venues they could to promote this boycott and create awareness of the war in China. They provided normal citizens the opportunities to create social change and help fight the Japanese from home. By naming simple things that they could substitute for non-Japanese made products, these citizens believed that they were creating peace and fighting an Axis power. By creating leaflets, buttons, picketing, and urging people to create boycott committees, the WCF was able to drill the idea of the boycott into peoples’ brains.

However, it was shocking to me that the WCF and boycotters cared so little about the local businesses that were being affected. Dockworkers were at risk of losing work with the talk of an embargo, yet the WCF continually pushed for it. They forcefully picketed local stores who sold more than just Japanese-made goods, and forced them to get rid of their inventory and quit selling Japanese products. More likely than not, the storeowners had already paid for all the goods, so by forcing stores to get rid of their inventories, the boycotters were only financially hurting small storeowners, and not the Japanese economy.

It is also instructive to see how many of the stories and statistics that The Sunday News claimed to be true were exaggerated or uncited. Many pamphlets and leaflets had specific facts and export numbers tied to silk production but many of the publications had numbers that were not clearly cited. It is interesting to see how effects were exaggerated. To me personally, it would seem very odd for an organization like the WCF to uncaringly push this boycott of goods, putting so many jobs at risk. They do not seem to think strategically in their boycott, simply naming off goods and stores where these goods are sold.

The boycott was never intended to be a boycott against ethnically Japanese people, though it did help contribute to anti-Japanese sentiment. WCF leader Hugh DeLacy did an excellent job of reminding the public in The Sunday Times that the boycott did not mean boycotting Japanese Americans. DeLacy reminded the public that most Japanese people in the US country were just like other citizens: they own small businesses and restaurants, they deliver mail, and they are students. None of these people, DeLacy argued, were attacking innocent lives in China.[19] Despite DeLacy’s article, though, the WCF’s extensive push for the boycott naturally spilled over into anti-Japanese propaganda. From protesting Japanese products to protesting Japanese culture: anti-Japanese shows were used to promote the boycott of both Japanese culture and goods.[20]

An article that ran in the Japanese-American Courier on December 11, 1937 declared that the boycott had gone too far. The article told the story of a Japanese Great War veteran now living in the US, married to an American woman, had been boycotted from purchasing simple American products like vegetables and flowers. This was hurting his own business, and making it impossible for him to provide for his family. The article also mentioned a Japanese American child that was attacked at school and sustained broken ribs due to anti-Japanese sentiment.[21] This racially motivated backlash was what most Japanese Americans were afraid of. Unfortunately, with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the entire nation’s attitude toward Japanese Americans became negative, and led to the internment of thousands of Japanese Americans. And despite their otherwise left-leaning program, the WCF—due to an anti-Japanese politics primed by the boycott campaign—supported Japanese American internment as part of the American war effort.

The boycott never really found an end. The consumer boycott of Japanese-made goods like silk was most prevalent in the holiday shopping season of 1937 and lasted through the first half of 1938. But The Sunday News published less and less about the war and even less about the boycott in the second half of 1938: the column break “BOYCOTT JAPANESE GOODS” disappeared, and most articles began to focus less on consumer goods and more on protests of shipments to Japan, lessening the grassroots focus of the boycott campaign. More emphasis was put on Hitler and Nazi Germany, as they became a stronger power after signing the non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union.

The boycott of Japanese goods was intended to be a boycott of goods with Japanese ties. It was never meant to be a boycott of Japanese American vendors or businessmen, or a racial boycott of the Japanese Americans. But it became easy for citizens to discriminate against many loyal Japanese Americans. The WCF effectively used their power and persuasion to create numerous committees to boycott Japanese goods. The boycott proved effective, as many vendors of Japanese-made products showed signs of a decrease in sales, and Japanese exports ended up falling as well. The WCF was very influential during this time period and was able to rally citizens to boycott a cause they felt was unethical. In the end, their single-minded commitment to the campaign acted as a stepping-stone in the further discrimination of Japanese Americans.

Copyright (c) 2009, Chris Kwon

HSTAA 353 Spring 2009

[1] “WCF ask U.S. to Ban Japan Shipments,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 24 July 1937, p.1.

[2] “WCF asks Boycott of Japan Goods; Schwellenbach Urged For Court Post,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 7 August 1937, p.1.

[3] “Nine-power Treaty,” HowStuffWorks.com, 27 February 2008, accessed 20 May 2009, <http://history.howstuffworks.com/asian-history/nine-power-treaty.htm>.

[4] Albert Anthony Acena, “The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front,” unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, (Seattle: University of Washington, 1975), p.199.

[5] “Japan Aided In Invasion by U.S. Military Cargo,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 14 August 1937, p.1.

[6] “Civic, Religious, Labor Heads Want Action on Crisis,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 21 August 1937, p.1.

[7] “Mr. & Mrs. Seattle Favor Boycott of Japanese Products to End War,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 30 October 1937, pp.1 and 4.

[8] “Relief For China Sought by Group,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 2 October 1937, pp.1 and 4.

[9] “WCF Women Switch to Cotton Stockings; CIO, AFL Support Boycott,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 16 October 1937, p.1.

[10] “Japan Admits it’s Feeling Boycott,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 16 October 1937, p.1.

[11] “Kress, Rhodes, Woolworth 5-and-10 Stores Carry Big Japanese Stocks,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 6 November 1937, p.1.

[12] “Youth to Picket Stores Selling Japanese Goods,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 20 November 1937, p.1.

[13] “Bombing of ‘Panay’ Spurs Boycott Drive,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 18 December 1937, p.1.

[14] “Boycott Ruined Xmas Sale of Japan Goods,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 31 December 1937, p.1.

[15] Minutes of the Proceedings of the Conference on Boycott of Japanese-Made Goods sponsored by the Washington Commonwealth Federation, January 15, 1938, Robert E. Burke Collection, Accession 2874-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 3, folder 9.

[16] Miscellaneous speeches, n.d., Robert E. Burke Collection, Accession 2874-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 3, folder 10.

[17] William E. Dodd Jr., open letter, October 26, 1937, Robert E. Burke Collection, Accession 2874-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 8.

[18] Howard Costigan, letter to King County officials, January 3, 1938, Robert E. Burke Collection, Accession 2874-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 8.

[19] “Boycott and Race Prejudice,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 29 January, 1938, p.2.

[20] “Sparkling Anti-Fascist Style Show is Planned,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 5 February 1938, p.4.

[21] “Misery and Death Caused By Boycotts,” Japanese-American Courier (Seattle, WA) 11 December 1937, p.1.