by Nathan Riding

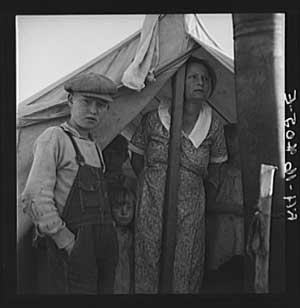

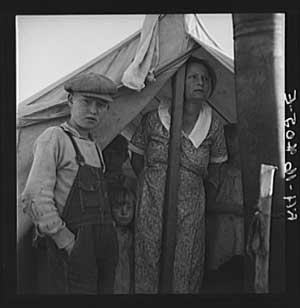

Rural poverty, inadequate state infrastructure, and the economic crisis of the Great Depression spurred a movement for an income tax led by rural farmers in the Washington State Grange during the 1930s. The measure faced stiff political opposition, and as in this 1939 photograph by Dorothea Lange, taken in the Yakima Valley shows, poverty and lack of infrastructure and social services continued through the 1930s. (Photograph Courtesy of American Memory, FSA/OWI photographs, fsa 8b34283.)

Washington State is one of the few states in the country to never implement an income tax, giving it the dubious distinction of being the state with probably the most regressive and inequitable tax system in the country. Yet an income tax was passed by popular vote in the midst of the Great Depression, as a movement spearheaded by the farmers of the Washington State Grange sought to lessen their tax burden and promote a more equitably gained source of revenue to support the growth of Washington’s infrastructure and state services.

The movement for an income tax in 1930s Washington was primarily a revolt against the inequity in the tax system rather than a movement for the income tax in particular, so when the state government was able to reform its tax system by lessening the immediate burden of property taxes yet without passing an income tax, support for an income tax partially deflated. However, the State Grange sought year after year to introduce an income tax measure onto the ballot, only to face stiff opposition from the state government and direct overturnings of the popular vote by the State Supreme Court. This study draws from Philip J. Roberts’s recent work, A Penny for the Governor, a Dollar for Uncle Sam: Income Taxation in Washington,[1] as well as important primary sources, to investigate the history of the movement for an income tax in Washington State, and to understand how Washington has continued into the twenty-first century without a stable or equitable source of state funds.

During the Depression years, many people found themselves with little or no income. Rural Washingtonians strongly favored a state income tax as the fairest way to relieve a property tax burden that many no longer had the ability to pay. Support for the income tax was led by the Washington State Grange, an organization dedicated to improving the lives of farmers through cooperative economic and political means. The Grange ultimately failed due to the governor’s veto, judicial intervention, and the adoption of alternative taxation schemes by 1935. These new tax laws relieved the pressure on farmers and workers from the property tax and thus diminished support for the income tax. Despite the lagging support, however, the Washington State Grange unsuccessfully continued to push for the adoption of the income tax in 1936 and 1938, and the state legislature took up the cause in 1941. The quickly shifting priorities of people in an economic emergency was insufficient for passage of a State income tax in lieu of other taxation schemes that sufficiently relieved the immediate burden of property taxes at the time.

Examination of the history of the State income tax during the last great economic crisis can provide insight into solving our current state revenue challenges. The failure to enact a state income tax in Washington State during the Great Depression has left Washington with a tax system extraordinarily vulnerable to the up and down swings in the economic cycle. The current economic recession, the worst since the Great Depression, has focused policy makers’ attention on the current tax system of Washington State due to the resulting multi-billion dollar budget deficit. The state’s current antiquated tax scheme of excise, sales, and corporate taxes originally instituted during the Depression era has left a legacy of regressive taxation and unreliable revenues.[2]

The current crisis has moved many policy makers to reconsider the viability of instituting a state income tax in order to solve the issues of inequity and the inability of government to generate revenues that can keep pace with the rising cost of government services. Examination of the history of the state income tax during the last great economic crisis may provide insight into solving our current state revenue challenges.

Tax Reform Politics in the 1920s

From its territorial days until the Great Depression, Washington State’s government relied upon property taxes to fund its activities. Property taxes were a relatively equitable and reliable tax system, as those with more property paid more taxes and many Washington residents owned property because of the significant number of farms.

Washington's roads -- like this one, from 1927 -- were in desperate need of repair, and needed maintenance to accommodate new modes of transport. Washington's tax system was inadequate in dealing with these, and other, infrastructure problems. (Photo by Webster and Stevens, courtesy of Museum of History and Industry).

But a great deal changed during the early twentieth century. In 1900, six of ten Washingtonians still lived on farms.[3] By 1930, Washington’s population tripled to 1,563,396 and the rural farm population shrank to around 300,000, making up only 19% of state’s population.[4]

As the population grew, so did the demand for government services. New roads were needed to accommodate the automobile and more revenue was needed to meet the escalating cost of public education. The legislature passed a one-cent tax on gasoline in 1921 to help meet revenue demands for new roads and increased it to two cents in 1925. However, the state government’s need for revenue continued to rise and the legislature remained reliant on property taxes to satisfy the state budget.[5] By 1920 property taxes had doubled in ten years.[6] Farmers became major contributors to state revenue disproportionate to their population in the state. In 1930, the State Tax Advisory Commission acknowledged the pressures on property owners in relation to the growth of government and the original intent of the property tax, writing in a petition:

"The tax system of Washington, in the main, was established when the ownership of real and tangible personal property was a fair measure, if not the only measure, of taxpaying ability. This system imposed almost the entire cost of government upon the owners of real and tangible personal property…. Since Statehood the scope of government has expanded beyond the bounds that then could have been contemplated. Likewise the forms of wealth of this State have changed along with the expansion of the economic life of its citizens…. Many States have met this enormous increased cost of government by providing method of taxation whereby the tax burden is equalized…."[7]

At first, the demands for tax reform took the shape of caps on taxes that the state could levy. In 1924, a group called the Federation of Taxpayers made up of farmers and realtors worked to collect signatures and successfully placed on the ballot an initiative limiting the combined property tax levy for all government entities, state and local, to 40 mills ($40 tax per thousand dollars of assessed value).[8] The measure was defeated, but the effort reflected the frustration of property owners regarding the growing property tax burden.

The West Coast was already in recession before the Great Depression officially began. The region’s manufacturing industries were hard hit by the rapid demobilization of the U.S. following the end of World War I, which also affected its mining and timber industries. Growing global recession in 1927 also hit the Northwest because of the dependence of the region’s farming and extractive economies on world trade. The effects of this depression were felt in the rural parts of Washington by 1927. The agriculture industry throughout the country had experienced deep decline during the 1920s, seeing 5 billion of its 18 billion dollar income wiped out.[9]

The growing economic recession in the Northwest motivated the Washington State Grange, a fraternal farm organization working for the social and political welfare of farmers, to lead the fight to reform the tax system and to provide tax relief to farmers even before the Great Depression began. The depressed agricultural industry coupled with farmers bearing an increasingly greater load of the tax burden made tax reform a top priority for the Washington State Grange. In 1928, the Grange supported a change in the constitution that would have allowed for the taxation of intangibles such as stocks and bonds. Despite their support, the measure was narrowly defeated in the 1928 election. Undeterred, the Grange turned their efforts to the income tax.[10] In the 1929 legislative session of the state assembly the Senate passed a state tax on personal income. Unfortunately, the legislation in the House was never brought up for a vote. The legislature did pass a corporate franchise tax on net income, but the legislation included exemptions for commercial banks. Smaller savings and loan firms challenged the

law in court in the case Aberdeen v. Chase, which the Supreme Court overturned. The court reasoned that all banks had to be treated equally, and in this case the exemptions for larger banks violated the equal protections provided by the 14th Amendment to the Constitution.[11]

Farmer Radicalism in the Emerging New Deal Coalition

By the 1930s all of Washington State was feeling the full effects of the Great Depression and the stock market crash of 1929. In an article in the Grange News, State Master Albert Goss describes the pitiful situation of many in Seattle during the time:

" Yesterday I walked through several blocks and alleys between First and Second avenues and Second and Third avenues in Seattle, and saw men running through the garbage cans looking for something to eat, ––not one but many. Last night I saw hundreds of men who had been standing in line possibly an hour, waiting for the doors of a soup kitchen to open where they could get a free bowl of soup. A few days ago I saw a crowd of men congregated before the “Millionaire’s Club” waiting for the tri-weekly distribution of dry bread, saw these men tear off the newspaper wrappings and devour a half loaf in a few moments like ravenous animals."[12]

This paper draws on Philip J. Roberts' 2003 book, published by the University of Washington Press, which examines the social and political battles over tax policy in Washington State.

Goss’s writing showed how farmers began to see their plight as connected to those of the poor and working classes in cities. At least the farmer didn’t go hungry, touted the Grange. However, farmers had suffered for years under difficult economic conditions, and could find empathy and potential common cause with others.

But whereas the urban poor had no food, the bigger problems for the farmer were that most of his capital was wiped out and his taxes were unpaid.[13] The heavy reliance on property taxes began to take a toll on revenue collection during the 1930s, underscoring the dire situation property owners faced. A report from 1956 done by the Washington State Research Council found these figures: "The property tax for 1929 was $78 million––$70 million (90 per cent) was collected;

in 1932 the property tax was $73 million––$51 million (70 per cent) was collected;

in 1933, the property tax was $66 million––$47 million (77%) was collected….

State taxes fell from $20.7 million in 1931 to $16.8 million in 1933, a loss of some 20 per cent––even with almost an additional $1 million from the new business and occupation tax."[14]

Charles Hodde, a Grange Master, Grange lobbyist, legislator, and eventual Speaker of the Washington State House of Representatives during the Depression, summed up the problem in an interview in 1997: “Here we were in entering the ’30s, and the cost of government didn’t decline as fast as the revenues of the people when prices dropped.”[15] At the time, the law allowed property taxes to go unpaid for up to five years before foreclosure could commence, so many farmers without profitable farms––which were many––had no choice but to let their taxes go unpaid. In Chelan County less than 50% of taxes were being paid in 1932.[16]

The Washington State Grange had previously been very active on tax reform issues, but by 1930 the desperate situation of the farmers spurred the Washington State Grange to greater action. The biggest problem for the farmers were taxes on property that had become a huge burden due to the drop in prices and loss of real values on their land. In 1929 Republican Governor Hartley, under pressure to address the difficult tax situation, recommended a special tax commission consisting of nine men to study the matter. The legislature agreed and the Governor appointed commissioners he viewed as sympathetic to his own position—opposition to the income tax—and charged them with submitting their report prior to the 1931 legislature.[17] The Grange was skeptical of the committee because it was predominantly made up of businessmen who had largely escaped paying taxes. However, the concerns of the Grange proved unwarranted.[18] As the report read: "After long and careful consideration of alternative revenue systems this Commission has come to the conclusion that the principal revenue system that this state should adopt for the relief of the property tax and to equalize the tax burden among all who have ability-to-pay should be based on the principle of measuring the tax by net income."[19]

The report of the special commission recommended that the state adopt a personal net income tax, a corporate net income tax, and recommended that the state derive its revenue from these sources rather than from the property tax in order to equalize the tax burden on Washingtonians. The property tax would be left to local government as their chief means of revenue collection.[20] The commission came out against the sales tax, Governor Hartley’s favored tax remedy, viewing it as a last resort to solving the property tax problem.[21] The commission’s findings validated the Grange’s long-held support for the income tax, and Grange members adopted a resolution in support of it.[22]

At the onset of the 1931 legislative session the Grange and other proponents of an income tax felt that their best chance to pass an income tax via the legislature had come. The Governor’s commission had recommended it and the full effects of the Great Depression created a climate for action that could buoy public support for lawmakers.[23] Early in the session, bills were introduced in both the House and Senate. One measure was the personal income tax and the other bill was an income tax on corporations.[24] By March, both measures had passed with large margins in each chamber and were sent to the Governor’s desk for signing.

On March 24th, Governor Hartley vetoed both the corporate and personal income tax bills. Hartley vehemently opposed the income tax. In his argument in support of his veto, Hartley claimed that the enforcement of the income tax would be too difficult and would require huge numbers of new workers to administer.[25] He also claimed that shrinking government and reducing costs would do far more to help relieve the tax burden than the income tax, and argued that the income tax would not stand judicial scrutiny.[26]

The Republican-controlled legislature and executive’s inability to come to agreement on a new tax program for the state contributed to Republican defeat at the polls. Hartley would run for re-election in the 1932 gubernatorial race but was defeated in the Republican primary largely due to his inability to adequately deal with the Depression and tax crisis.

Meanwhile, the Grange turned to the ballot initiative process––supported and passed by the Grange in 1912––to bypass the legislature and the governor and to provide a means of sound taxation for the state.[27] At the time, the Grange enjoyed a membership of nearly 30,000 members throughout Washington and was confident that it had the ability to collect the 60,000 signatures needed to qualify an income tax measure for the 1932 election.[28] The Grange carefully drafted the language of the initiative to avoid a repeat of the result in the Aberdeen case in 1929. The measure read:

"An act relating to and requiring the payment of a graduated income tax on the incomes of persons, firms, corporations, associations, joint stock companies, and common law trusts, the proceeds therefrom to be placed in the state current school fund and other state funds, as a means of reducing or eliminating the annual tax on general property which now provides revenues for such funds; providing penalties for violation; and making an appropriation from the general fund of the state treasury for paying expenses of administration of the act."[29]

The initiative qualified for the ballot in July and campaigning began in earnest, with the issue helping bring together Washington’s electoral coalition in support of New Deal Democrats in a state that had never had a Democratic Party majority in its legislature. The Grange knew that the rural vote alone would not be enough to pass the measure and sought to build support in the cities. The Grange gained the support of the Washington Education Association, the Seattle Labor Council, the Parent Teacher Association, the Unemployed Citizens League, and the High School Teachers’ League.[30] They set out to educate voters about the initiative and to gather signatures to win placement on the ballot. Charles Hodde was recruited by Grange State Master Goss to campaign for the measure in Seattle. “I went over there in September and I was there six weeks before the election. During that six weeks I drove 2,500 miles all inside the city of Seattle practically, and I averaged about seven or eight meetings a day.”[31]

In addition to the income tax, an initiative to cap property tax rates at 40 mills received enough signatures and was placed on the ballot similar to the failed initiative of 1924. The Grange took a neutral position on the matter. However, many of their urban allies like labor and education groups opposed the measure, and feared it would strangle schools and government without a replacement for the lost revenue.[32]

The result of the 1932 election was an historic Democratic landslide. Nationally, a new Democratic President, Franklin Roosevelt, and a Democratic Congress were elected. Democrats for the first time in history wrested control of Washington’s State government from the Republicans by electing a Democratic Governor, Clarence Martin, and by electing Democratic majorities in both houses of the legislature. The income tax initiative, I-69, passed by 70% of the vote, and I-64, the 40 mill limit, also passed.[33]

The overwhelming support by voters for the income tax initiative did not ensure its implementation. While the State Tax Commission began working out an administrative plan for the new law and began mailing out tax forms, opponents to the income tax filed lawsuits against the new law.[34] Just as in the Aberdeen case of 1929, the new income tax law was found unconstitutional in a 5 to 4 decision by the State Supreme Court in the summer of 1933. The court ultimately agreed with the original argument by lead counsel for the plaintiffs, Harold Preston, in Culliton v. Chase: “a flat tax would be permissible in Washington, a graduated net income tax would violate the constitution’s new uniformity provision because ‘income’ was ‘property’ and property was to be taxed uniformly.”[35] The income tax itself was not illegal, went the somewhat tortured legal argument; it was only a progressive income tax that was the problem, and thus “income” became equivalent to “property,” and the poorest farmer’s land was seen as equally taxable as a wealthy person’s bank account.

The Washington State Grange was outraged at the decision. The Grange News editorialized that “The courts are ruling America. The fact is that a government of the people, by the people, for the people has perished from this state if such decision as that invalidating Initiative No. 69 is allowed to stand.”[36]

Tax Alternatives

The loss of the income tax and passage of the 40 mills limit on property taxes made the state’s economic situation more, not less, dire. Jim Goodwin, secretary of the Davenport Commercial Club, wrote Governor Martin a handwritten letter saying, "Things are not improving any, are they: In this community, which is not a fault- finding community by any means, grumbling and objections are increasing. People simply don’t know how they are going to get by, and don’t know where to turn and grasp at anything they think might offer any relief."[37]

The need for government assistance further increased the pressure to find new revenue to help alleviate the suffering of so many. The state legislature, with new limits on their ability to collect property taxes due to the passage of the 40 mills limit initiative coupled with unconstitutionality of the income tax sought to find replacements to keep government budgets in the black and to address the increased need for economic assistance. The state had no choice but to turn to excise and sales taxes. In 1933, the state passed the business and occupation tax. At the end of 1933, the 21st Amendment repealing prohibition was ratified by the 36th state, opening the door for the regulation of liquor and the passage of excise taxes on alcohol.[38] In 1934, an excise tax of $1.00 per barrel of beer passed the legislature and was signed into law.[39]

Undeterred by court rulings, the Grange and supportive legislators passed a bill to amend the state constitution to allow for a graduated income tax after a vote by the people. The amendment received support by the Grange and was endorsed by the State Tax Commission. Despite their support, the Grange found reduced enthusiasm for the initiative among its own membership once the state had raised other taxes to cope with its fiscal emergency. The resulting support for the amendment on Election Day in 1934 was 134,908 in favor to 176,154 against, or only 43.4% of the vote.[40] The evaporation of support contrasted with the continued support and renewal of the 40 mills limit law. The property tax relief provided by the 40 mills law was reflected in its electoral success. The 40 mills law would continue to be renewed every two years throughout the decade until it was finally adopted as the 17th Amendment to the Washington State constitution in 1944.[41]

The steadfast support of the 40 mills limit and the continued defeat of the income tax forced legislators to find further replacements for diminishing property tax revenues. The legislature continued to experience drops in revenue due to the biannual renewal of the 40 mills law in 1934. From the period of 1931 to 1939, total property taxes declined by $40 million. Property taxes at the beginning of the 1930s made up 80% of total revenues and by the decade’s close dropped to just 42% of total state and local revenues totaling $40 million.[42] The legislature chose to overhaul the tax system by expanding excise and sales taxes, but did not give up hope on the income tax, and once again proposed legislation to institute a tax on net income.

The Grange supported the income tax bill and strongly opposed the sales tax. In an article in the Grange News the Grange declared, “The State Grange is a dyed-in-the-wool opponent of the sales tax.” The Grange argued that the sales tax, though “less painful because the payments come in small sums,” in the end was a “heavy burden” when “compared to the wealthy class.”[43]

The legislature moved ahead with their tax overhaul plans and passed the Revenue Act of 1935, creating the tax system that Washington State has had ever since. The act was signed by the Governor and passed judicial challenges that allowed for the creation of retail sales and use taxes, a business and occupation tax, a cigarette tax, admissions tax, fuel oil tax, and conveyance tax.[44] Legislators did not fare so well with the income tax bill, however. Lawmakers attempted to carefully word the income tax law to stave off any judicial challenges, but once again the Supreme Court struck down the law as unconstitutional, arguing that it violated the uniformity clause and the 14th Amendment.[45]

The 40 mill-limit law combined with the Revenue Act of 1935 made the adoption of other tax schemes unattractive to the voter. Charles Hodde in an interview said, “The tax system in place––the sales tax and the business occupation tax––wasn’t so obvious. Paying them was painless. People didn’t see what they had to pay a higher price for things because of those taxes.”[46] The Grange would try again in 1936 in an initiative to the people to pass the income tax and in 1938 without success.

Conclusion

The Washington State system of taxation in its early days was fair and equitable. Taxes were measured based on real property, as most of the wealth of the state was found in land. As the state grew and the demand for government services expanded so did property taxes. Property owners increasingly bore the lion’s share of taxes to support government services. Change in lifestyles and ways of accumulating wealth made the state tax system reliant on property taxes antiquated and unequal.

The onset of the Great Depression intensified the burden on the property owner. Taxes throughout the state went unpaid and state coffers were diminishing at a time of increased demand for state services. This climate created a crisis that forced the state to

overhaul the tax system. The tax system was studied and a tax on net income was deemed to be the best solution to the revenue crisis. By 1932, income tax proponents passed the income tax by a large margin in a vote by the people but the measure was struck down as unconstitutional in conjunction with the passage of property tax limits.

The combination of property tax limits and continued judicial interference made the passage of an income tax in successive attempts futile. The inability to tax income forced the legislature to look for revenue replacements in excise and sales taxes. Once these replacements took hold, people no longer felt compelled to support the income tax as government finally received adequate revenue. In addition, under the 40 mill-limit law, property taxes were no longer burdensome and thus immediate need that had sparked the Grange’s income tax movement had been mitigated. The longstanding support of the income tax by the Washington State Grange would remain, but the legacy of the Great Depression on the state tax system would be the Revenue Act of 1935 and not the income tax.

Epilogue

The Washington State Grange would continue its attempts to pass an income tax with the support of the Democratic-controlled legislature by a vote of the people in 1936 and in 1938. The Grange and the Democrats continued to believe that a progressive income tax was the fairest means to collect revenue for the state. Unfortunately for proponents, attempts to pass a constitutional amendment allowing for an income tax were defeated in landside opposition to the measure in 1936 and 1938. The legislature made a final attempt to send the income tax measure to a vote of the people in 1941 but lost 2 to 1.[47] The support for the income tax experienced by the Grange in 1932 had evaporated, and further attempts pass it produced outcomes in reverse of their earlier their electoral successes.

The failure to pass the income tax forced the state to rely on the Revenue Act of 1935 as the main source of revenue for the state. Today sales and excise taxes remain the mainstay of revenue. State leaders since the Great Depression era have tried several times to implement a state income tax but have always failed. Perhaps not until economic conditions similar to those experienced during the Great Depression are again upon us will proponents of the income tax find sufficient support to finally pass it into law.

Copyright (c) 2010 Nathan Riding

HSTAA 498 Winter 2010

[1] Philip J. Roberts, A Penny for the Governor, a Dollar for Uncle Sam: Income Taxation in Washington (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002). Most of the page citations that follow are from Roberts' PhD dissertation, “Of Rain and Revenue: The Politics of Income Taxation in the State of Washington 1862-1940” (PHD Diss., University of Washington, 1990).

[2] Rachel A. LeMieux., “A Discussion and History of Taxes in Washington” (Washington Sate Department of Revenue, Centennial Committee, 1982), 19.

[3] Roberts, “Of Rain and Revenue," 13.

[4] Historical Census Browser, http://mapserver.lib.virginia.edu/php/State.php (accessed Feb.19, 2010).

[5] Report of the Tax Advisory Council of the State of Washington, Proposal For Changes In The Washington State Tax Structure, Olympia, Dec. 1966, 100.

[6] Roberts, “Of Rain and Revenue," 146.

[7] Petition for Rehearing of the Tax Advisory Comm’n at 2-3, Aberdeen Savings & Loan Assoc. v. Chase, 157 Wash. 351, 289 P. 536 (1930) (No. 22228), reh’g denied, 157 Wash. 391, 290 P. 697 (1930).

[8] Roberts, “Of Rain and Revenue," 148-149.

[9] “The Cause of the Depression and the Cure” The Grange News, Jan. 20, 1933, 1.

[10] Hugh D. Spitzer. “A Washington State Income Tax–Again?” University of Washington Law Review, vol. 16, (1992-1993): 525.

[11] Spitzer, 526.

[12] A. S. Goss, Is It Courage We Lack?” Grange News, Oct. 5, 1931.

[13] Ibid.

[14] John F. Sly, “Deep in the Heart of Taxes, Tax Developments in Washington State–How We Got This Way” (Washington State Research Council, 1956), vol.1, 9.

[15] Boswell, Sharon, “Charles W. Hodde, An Oral History”, (Washington State Oral History Program, 1997), 1.

[16] Boswell, 2.

[17] “Income Tax Advocate Heard,” Washington State Labor News, Jul. 1, 1932, p. 1.

[18] “The Governor’s Tax Commission”, The Grange News, Nov. 5, 1929. 1 & 5.

[19] Tax Commission, 1929-1930, Vol. 2 pp 40., Washington Public Document.

[20] Sly, 7.

[21] “State Board’s Heart Set On Income Tax”, Spokane Chronicle, Nov. 10, 1930.

[22] Roberts, “Of Rain and Revenue," 163.

[23] Roberts, “Of Rain and Revenue," 179.

[24] “Legislature Opens in Washington,” Farm Bureau News, Jan. 22, 1931.

[25] Roberts, “Of Rain and Revenue," 143.

[26] Roberts, 143; and “Lights and Sidelight on The Legislature”, Bainbridge Review, Mar. 5, 1931.

[27] Boswell, 3.

[28] Roberts, “Of Rain and Revenue," 191 and 196.

[29] “Ballot Initiatives: Wording for Initiative 69.” Secretary of State’s Office, memorandum to all newspapers of general circulation in Washington, Oct. 1932.

[30] Roberts, “Of Rain and Revenue," 194.

[31] Boswell, 1.

[32] Roberts, “Of Rain and Revenue," 198-199.

[33] Roberts,“Of Rain and Revenue," 202.

[34] Roberts, “Of Rain and Revenue," 232-233.

[35] Spitzer, 531.

[36] “The People vs. The Supreme Court”, The Grange News, Sept. 20, 1934. 6.

[37] Martin, Clarence D., Secretary of State, Department Tax Commission 1933-1940, 2L-166.

[38] Roberts, “Of Rain and Revenue," 248.

[39] LeMieux, Appendix B.

[40] Roberts, “Of Rain and Revenue," 254.

[41] Sly, 7-8.

[42] Sly, 11.

[43] “Sales Tax Unalterably Opposed”, The Grange News, Dec. 5, 1934.

[44] “Income Tax Nullified”, The Grange News, Jan. 18, 1936. 1.

[45] LeMieux, 14.

[46] Roberts,“Of Rain and Revenue," 280.

[47] Sly, 10.