by Zachary Keeler

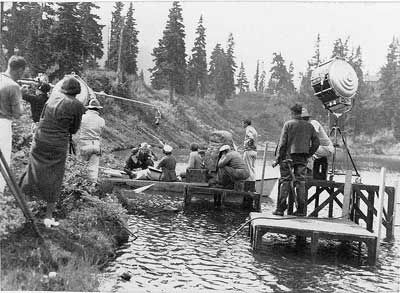

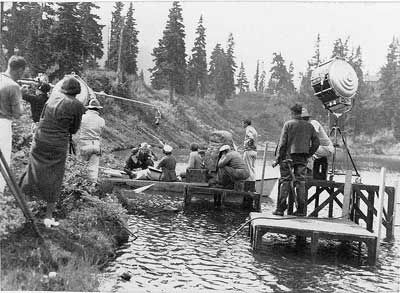

A film crew shooting The Barrier at Mt. Baker, a 1937 film starring Jean Parker. Major Hollywood studios set many of their films in Washington State during the Depression, capitalizing on the region's beauty and creating a mutually beneficial relationship between Washington's tourism and workforce and Hollywood's needs for beautiful settings and labor. In The Barrier, Mt. Baker was supposed to stand in for the Alaskan tundra. Click the image to enlarge. (Photo courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collections)

In the midst of the Great Depression, the entire country and world alike experienced the woes of a failed economy and general decline of living conditions. During this same time, in the late 1920s and into the 1940s, the American film industry experienced a boom that would later be regarded as Hollywood’s Golden Era. While the country was consumed in a sullen attempt to rebuild society, films offered an accessible escape for restless minds in tough times. During the 1930s, the entire film industry transformed and “Hollywood” became synonymous with big studio pictures and became the standard for movies around the world. Films became cheaper to produce as studios vertically integrated the production process, which allowed the price of film attendance to go down. When synchronized sound replaced silent films, it made films more accessible and desirable to the illiterate. As films reached new and wider audiences, actors increasingly became idolized as stars, further intensifying the hype of the industry.

However, it wasn’t just film prints that reached new audiences during the 1930s. The success of the Hollywood film industry allowed it to expand beyond the Southern California movie sets to film in increasingly more authentic and spectacular locations. This had a great effect on the nation’s imagination and film culture that impacted individual states, cities, and local communities in specific ways. Movie-making in Washington State during the 1930s provides a window into this process. It created a mutually beneficial relationship in which film production brought Washington establishments, cities, and towns exposure while Hollywood used the scenic beauty of the state as a pragmatic alternative to filming farther abroad or in a studio. Examining films shot in and depicting Washington throughout Hollywood’s Golden Era shows that Hollywood used the state mainly for its scenic beauty and outdoor images, while Washington residents used Hollywood’s stars and production presence both to promote the state’s recreational culture of arts and outdoor activities, and to stimulate economic development in the midst of the Depression. And despite occasional tensions between local residents and state governments about usage of the state’s outdoors, or differences between Hollywood’s portrayal of Washington and Washington’s promotion of its region, both sides seemed to gain economically and culturally.

There were six big box office Hollywood films and three documentaries shot in Washington during the Depression. The six box office films are MGM’s Tugboat Annie (1933), Warner Bros.’ Here Comes the Navy (1934), 21st Century Pictures’ The Call of the Wild (1935), and Paramount Pictures’ The Barrier (1937), Warner Bros. God’s Country and the Woman (1937), and 20th Century-Fox Pictures’ Thin Ice (1937). Another film, Paramount Pictures’ Ruggles of Red Gap (1935), was filmed in California but depicts a fictional rural Eastern Washington town. The mutually beneficial Hollywood-Washington film relationship is shown both in the film genre made possible by using this new scenery and in their production aspects as revealed through articles in the Los Angeles Times and the Seattle Times. Four shorter documentary-style movies were also shot in the state and included Warner Bros.’ Believe it or Not (1932), Vitaphone’s Can You Imagine (1936), and MGM’s Seattle: Gateway to the Northwest and Glimpses of Washington State (1940). These films generated far less media coverage, so the evidence surrounding their connection to Washington lies primarily in their content. In addition, historian Colin Shindler’s Hollywood in Crisis: Cinema and American Society 1929-1939 provides great insight into the birth of Hollywood as a major industry in both the business world and as a creative force for a new art form, and is used throughout the paper for context of Hollywood on the national scene.

Washington’s relationship with Hollywood began long before the Golden Era, as many independent and short films had been shot in the state. Shindler describes the beginnings of the Golden Era by stating that after WWI there was a surge in consumer spending, with Hollywood one of the most fortunate recipients, leading to a great growth within the industry.[1] Thus the booming 1920s economy in part fueled Hollywood’s rise. But it was another invention that allowed the success of film to carry into the Depression: Shindler notes that by 1929, the sound revolution had led studios to consolidate, and that Los Angeles grew from a few hundred thousand residents just a few decades earlier to over a million.[2] Fewer studios meant more power for the ones that survived, which allowed for the expansion of Hollywood movie houses and films on the national level.

Shindler explains that there came to be five major studios in Hollywood: Fox (later Twentieth Century-Fox Pictures), Metro Goldwyn Meyer (MGM), Paramount Pictures, Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO), and Warner Brothers (Warner Bros.). Each studio vertically integrated their companies to include every aspect of production and consumption under one roof, from stables of writers and actors to equipment, studios, and movie houses.[3] It was this great concurrent expansion and consolidation of the film industry that would give new meaning to films produced in and featuring Washington. Without the consolidation and mounted power of the big film studios, it is unlikely that American film would have expanded to the degree that it did during the Great Depression, limiting both its audience, its ability to shoot outside California, and the kinds of films it could produce.

The first major Hollywood filming in Washington during the Golden Era was similar to earlier productions in the state. Ripley’s Believe it or Not series produced by Warner Bros. brought strange and “abnormal” stories from around the world to the big screen for movie patrons at Warner Bros. theaters, and among the stops in Ripley’s 1932 circuit was Tacoma, Washington.[4] Actual footage could not be located, as Warner Bros. likely has the film stashed deep in their archives. However, a clipping from a 1954 Seattle Times ad posted by the Evangel Temple reads, “Fred Henry, famous blind pianist playing and singing. Hear the man who was once featured in Ripley’s ‘Believe It or Not’, all ages welcome.”[5] It seems, whether or not Henry was the same person featured in the 1932 episode of Ripley’s, that being filmed in a Hollywood feature carried prestige well over twenty years after the fact. This short publicity ad gives only a glimpse of Hollywood’s lasting influence on Washingtonians, as full feature films would soon hit Seattle and enthrall thousands. Ripley’s show was important as it marked the introduction of big film in Washington during Hollywood’s Golden Era, but it did not necessarily affect the state’s economy or exploit any of its natural beauty like most other films of the time.

The tugboat Sea King, pictured above, played the role of Annie's competitor in the 1933 MGM film Tugboat Annie. The film was the first major film shot in Seattle, and follows the stories of a tugboating family in Washington State. MGM decided to shoot the film in both Los Angeles and Seattle, using shots of Seattle's waterfront and mountain scenery to bring an authentic feel to the picture. Tugboat Annie marked the true beginning of Hollywood's relationship to Washington State, as State boosters used the film's publicity to bring tourism to Washington. Click on the photo to enlarge. (Photo courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collections)

The next big film to hit Washington was MGM’s Tugboat Annie in 1933. Originally written by Norman Raine as a series of short stories, the film draws from Raine’s writings to chronicle the struggles of a Socoma, Washington family on a Puget Sound tugboat. In 1932, the Seattle Times interviewed Raine to learn about his inspiration for writing the short stories that would subsequently bring Hollywood to Washington. According to the interview, Raine had been visiting the University of Washington in 1930 at the request of professor Vernon McKenzie from the Journalism School, and while in Seattle wrote a short story about the tugboat industry along Seattle’s waterfront.[6] But how did Hollywood producers pick up the short stories for the silver screen? Raine briefly explains in a 1932 Los Angeles Times interview, “The Saturday Evening Post bought the story and my agent asked for a copy of it to submit to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.”[7] While the story was set in Puget Sound, MGM would have found it more financially viable to shoot the film on a Los Angeles set.

Luckily for Washington, MGM made a compromise and decided that both Seattle and Los Angeles would be used to film Tugboat Annie. A Los Angeles Times article from 1932 stated, “Part of Seattle waterfront was reconstructed on Hollywood studio lot to give proper background to play.”[8] Thus Hollywood had found a way to cut the costs of shooting the film entirely in Seattle, which would require hotel rentals, equipment shipping, and various other expensive costs. However, portions of the film shot in Seattle seemed integral to the story’s success and visual attraction, as scenes of Seattle’s waterfront and surrounding neighborhoods serve as the capstone of the film’s dramatic ending. In fact, a 1933 Seattle Times article claims that the movie “has its locale in Seattle and all the outdoor pictures were made here by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer this Spring… pictures of Lake Union, Queen Anne Hill, the Eastlake district, the Port of Seattle’s great terminal, and a great ‘shot’ of the Olympic Mountains.”[9]

A Seattleite in 1933 would find much excitement in seeing their local neighborhoods used in Hollywood films, which perhaps explains one of the reasons MGM producers decided to film in Seattle. While the scenes would be familiar, Hollywood had the ability to make them extraordinary by featuring the city through special camera techniques, views otherwise unseen, and cuts to multiple shots on the big screen of a movie theater. People wanted to be part of the excitement. Another 1933 Seattle Times article notes that over 5,000 people, prompted by the City of Seattle, showed up to be extras in the finale scene of Tugboat Annie without pay or recognition. Seattle officials are said to have felt that the film would bring good publicity to the city.[10] Surely though, the prospect of being in a major Hollywood film screened across the nation was a personal incentive for Seattleites who battled crowds to be in the picture. Thus Seattle’s popular culture was becoming increasingly geared toward film, accentuated by Hollywood’s decision to shoot on location in the city. Box office results would soon show that MGM’s efforts had paid off.

The release and reviews of Tugboat Annie show how Washington State boosters used Hollywood films to bring business and cultural recognition to their state. Typically big film studios premiered their films in Hollywood and invited actors and the press to draw publicity, but the Evergreen State Theatre’s president Frank Newman fought to bring the premier of Tugboat Annie to Seattle. According to a 1933 Seattle Times article, “Mr. Newman was forced to enter into some lively bidding with Sid Grauman, owner of the Hollywood Chinese Theatre, for the right to stage the world premiere of “Tugboat Annie’ […] it isn’t too often that Seattle gets a world premier.”[11] Perhaps Mr. Newman simply felt the film would sell well to Seattle audiences and draw healthy box officer numbers, but as the hordes of people gathered to be part of the film there was a definite sense of pride in the film’s local production. Indeed, reviews of the film reveal that it was a hit at the box office not just in Seattle but across the nation. Thus Washington had a huge success with its first big Hollywood-backed production and premiere, and its scenery became shown to eager theatergoers across the nation.

In 1934, Warner Bros.’ came back to Washington with their romantic comedy Here Comes the Navy, which featured scenes filmed aboard the USS Arizona at the Bremerton Naval Yard. The plot of the movie features a young man who joins the Navy to get even with a Naval officer, whose sister he ironically eventually falls for. The movie also centers on the might of the Navy, as romantic views of battleships and men in uniform constantly fill the screen. However, while a Washington waterfront was again being used by Hollywood, this time the specific location appeared to be less important. A Seattle Times reviewer merely wrote that James Cagney, star of the film, suffered rope burns and boasted that “The entire US Pacific Fleet also plays a part in the film.”[12] Whether it was just a lack of media coverage or interest in general, there seems to have been little attention to the specificity of the film’s Washington production compared to that of Tugboat Annie. One explanation is that because the film was shot at a Naval base instead of a public area, it was too far from the public eye and less accessible, or that the storyline rendered the specific location less important to the plot of the movie.

Another explanation of the comparative disinterest in Here Comes the Navy is given in Philip Scheuer’s Los Angeles Times review of James Cagney’s pictures. In his mostly negative review, Scheur wrote that Here Comes the Navy was both pretentious and too complex.[13] Thus it seems that neither Washington nor Hollywood benefited much from the film. However, the film would later take on a new meaning for historians, as the USS Arizona was sunk in the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, which eventually led the country into war that brought the end of the Depression.

Washington State's Mt. Baker was chosen as the setting for the Twentieth Century Fox's 1935 film adaptation of Jack London's Call of the Wild. Mt. Baker's relative isolation and harsh climate were chosen as a cheaper and more logistically feasible alternative to filming in the Alaskan Yukon, where the story takes place. Shown here are a group of mountaineers in 1925 attempting an ascent. (Photo by Clyde Banks, courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collections)

Just a year later Hollywood would return to put Washington back into the top ranks of film. In 1935, Twentieth Century Pictures’ released The Call of the Wild, an adaptation of Jack London’s popular 1909 novel depicting sled dogs and the hunt for gold in the Alaskan Yukon. The film was by far the greatest success of the films shot in Washington during the Golden Era for both Washington and Hollywood. There had already been several versions of the novel adapted for film but none since the advent of sound technology and none with energy and financial might of Hollywood’s Golden Era studios. Hollywood producers decided to shoot scenes for the film at the Mt. Baker Lodge just outside of Bellingham, Washington. The result was economic stimulus for the otherwise isolated area and increased efforts by local boosters to use the allure of film stars and filming crews in shaping the area’s recreational culture.

Ed Ainsworth’s 1935 article for the Los Angeles Times details the circumstances of London writing The Call of the Wild, stating that London was in the warmth and comfort of Southern California after having failed to make riches on an expedition in the Yukon. Ainsworth visited the home where London wrote the famous novel and talked to the owner, Felix Peano, who walked around the house showing off trinkets and memorabilia associated with London.[14] Clearly there was much interest in the film even before it was released. Indeed, a 1934 article from the Los Angeles Times reveals that the National Board of Review issued a survey to schoolchildren asking them what books they wanted made into movies, and Jack London’s The Call of the Wild was a popular pick.[15] Hollywood was doing their research to ensure that their films would be a success. With the addition of Clark Gable, Loretta Young, and Jack Oakie in the cast, who were all already popular Hollywood stars, it seems that Twentieth Century Fox would definitely have a hit at the box office with their new film.

During the production of The Call of the Wild, the movie made press all along the West Coast. The film is an excellent example of the mutally beneficial relationship between Hollywood and the set location: Hollywood used Washington’s scenic beauty to depict the grandeur and ruggedness of the London’s Yukon, while the state benefited from Hollywood’s cultural presence. But why was Mt. Baker chosen over other locations? A Seattle Times article from 1935 explained that Jackson Hole, Wyoming and Mt. Rainier, Washington were also considered for shooting locations to depict the Alaskan Yukon: "There were three sites considered for the production – and Mt. Baker, they understand there, gets the full production, not just the outdoor shots […] Jackson Hole had been filmed before. Mt. Rainier was felt suitable but with too many skiers swarming around. Baker was sufficiently remote to give fair guaranty [sic] that some skier wouldn’t come zipping over an unexpected hummock, sprang into a $5,000 scene, to ruin it."[16]

The site was thus chosen for its remoteness, but ironically the choice to film there facilitated the area’s transformation into a bustling site of wilderness tourism. The Mount Baker Development Company received a sum of $5,000 for shooting scenes as mentioned in the article, showing that local businesses were definitely benefiting from the Hollywood presence. One Seattle Times writer even projected the cost of filming at Mt. Baker to be $15,000 a day.[17] Furthermore, the Seattle Times estimated “The Filming will take two months at least; and it won’t do Mount Baker any harm. In fact it may assist in its world-wide development.”[18] Although Mt. Baker was the perfect setting for the film, the difficulties of shooting in the freezing climate are documented in scores of articles in both Seattle and Los Angeles newspapers. The state highway department decided to keep the roads plowed in order to assist production of the film, which then led to easier access for the public to Mt. Baker’s recreational activities.[19] Some of the issues film crews dealt with included poor weather conditions, sickness amongst the stars, and even a power outage.[20] Thus the difficulties of filming had an unpredictable effect of expanding the opportunity for winter recreation in the area, and fans from as far as Seattle would also use this opportunity to see their favorite stars on the set.

Local eagerness to see Hollywood in action in their own backyard produced a wave of excitement amongst state residents, and in some cases allowed residents to feel that the stories being filmed were partly their own. A 1935 Seattle Times article titled “Auto Caravan Bucks Blizzard to Mount Baker” details the trip of three cars trekking up to the lodge with hopes of seeing some Hollywood stars and the film’s production.[21] The fervor created by Tugboat Annie years earlier had returned to Washington, although this time people were willing to drive for over two hours in the snow just to watch the filmmakers without the chance of being part of the film. Some however, were lucky enough to be in the film. A 1935 Los Angeles Times article noted that “More than 200 former ‘Klondikers,’ veterans of the gold rush of ’98, took part in the scenes.”[22] With movie stars coming from Hollywood and miners from Alaska, it seems Washington worked as a perfect location between the two, and could even draw positive publicity to the towns passed through on the way to the filming site.A 1935 Seattle Times article announced to the city that the cast of The Call of the Wild would be passing through Seattle’s King Street station downtown. “The largest motion-picture company ever to be brought to the Northwest was due to arrive tomorrow afternoon.”[23] As Tugboat Annie had already been filmed in the city, people clearly felt The Call of the Wild was on another level, and reporters were quick to follow the stars’ every move.

When The Call of the Wild was finally released to the public in 1935, critics and fans were quite delighted with the results of filming in Washington. A Los Angeles Times article captured the excitement of the release, stating: “In Seattle, at the Orpheum Theater, ‘The Call of the Wild’ bought forth such crowds that the management was compelled to hold the picture over a second week,” and went on to report that this was a feat never before accomplished by the theater.[24] Thus aside from the press and popularity the movie acquired during its filming, at the box office people were equally enthusiastic about viewing the film. Washingtonians were likely interested in having the landscape of their state presented to audiences across the country, and film critics abroad were also pleased with the scenery. Schindler discusses what he calls the “anti-urban bias in films,” in which Hollywood frequently used portrayal of rural settings to provide a mental escape for urban viewers.[25] Indeed, in a Los Angeles Times article discussing the film’s success, the manager of Los Angeles’ Grauman Theater explains, “the unusual business we are doing with “Call of the Wild’ is I believe, [due] to the fact that audiences want Clark Gable in primitive backgrounds.”[26] This manager describes the backgrounds as “primitive” perhaps revealing the true “call of the wild” for Hollywood producers in choosing Washington as a setting, something at odds with how Washington boosters sought to promote their state as a sophisticated location connected with the Hollywood industry.

In a similar vein, another theater manager interviewed in the same article attributed the film’s success to its climatic incompatibility with urban spaces, noting that it was “an outdoor picture with a blizzard in the background, which appeals to the hot weather in the cities.”[27] Again, the manager addresses the escape sought by moviegoers during the Depression. Washington therefore, having provided the location for Tugboat Annie just two years earlier, offered a variety of scenery from city life to a remedy for city life. In many cases, Washingtonians were able to take pride in the beauty of their locations and view Hollywood’s interest as an exciting and glamorous event, while Hollywood sought both natural beauty but an authentic location for “primitive” environments.

Washington State could also stand-in as a marker for the rural and somewhat backward West. Warner Brothers' 1935 film, Ruggles of Red Gap, was set in a fictional town in Eastern Washington, and portrayed the struggles of an Englishman as he assimilated to the rough American West in the fictional town of Red Gap. Though the film was not shot in Washington State, is assumed that viewers would connect "Washington" with rural settings liked these scene of Pateros, in north-central Washington, in 1915. (Photo by Alfred S. Witter, courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collection)

The next feature film using Washington as a setting capitalized on the rural bias of Hollywood, with Washington State standing in as a remote Western region. The 1935 Warner Bros. film Ruggles of Red Gap was originally written by Harry Leon Wilson as a newspaper story and later adapted as a screenplay due to its great success. The film takes place in the fictional town of Red Gap, supposedly near Spokane, Washington, follows an ex-English servant named Ruggles who finds himself in a small rural Western town and is faced with the challenges of assimilating into American culture. By the end of the film, Ruggles has recognized the great opportunities America has to offer and becomes truly assimilated and accepted, reciting the entire Gettysburg Address to a barroom full of country folks. The film was and still is quite popular but because it was filmed in Hollywood and portrayed a fictional location it did little for the state of Washington. In fact, the film emphasized the un-specificity of Washington as a location, as Red Gap seems to stand in for any rural, Western location, emphasizing the cultural distance between Hollywood and Washington and the perception of Washington as a rough frontier state rather than the booming cultural center its boosters wanted it to be. Tellingly, a Seattle Times article discussing the film made no mention of its (fictional) regional setting, recounting only that “it is a rollicking comedy with a strong human appeal in it that no audience will resist.”[28]

For a few years, Hollywood took a brief break from using Washington in their films but would come back to share its prosperity with the state and use its scenic backdrops. 1936 saw the Vitaphone Corporation, one of the smaller film studios of Hollywood during the time, make a brief visit to Marysville, Washington to film a segment for their Can You Imagine series. Local newspapers produced no coverage of the event and it seems that the series, a takeoff of the earlier Believe it or Not series, was rather unsuccessful in gaining any real popularity. However, Hollywood would find its way back to the state.

In 1937, the last three big box office movies produced by Hollywood during the Depression were filmed in Washington. One saw the return of Warner Bros. to the region with God’s Country and the Woman, a story about the battle between members of a logging company that eventually fostered friendship within the camp but a feud with another company. The newly merged Twentieth Century-Fox Productions released another film called Thin Ice, which is the story of a European Prince and an aspiring figure skater who eventually fall in love despite a rocky beginning. Lastly, Paramount Pictures visited the state with The Barrier, a romantic-thriller taking place in the Alaskan tundra.

God’s Country and the Woman likely found its way to Washington because Tugboat Annie’s writer Norman Raine drafted the screenplay for the film. However, the film was unique from previous Washington sets because it employed Technicolor filming technology. Technicolor was key to other popular films of the time such as Walt Disney Productions’ 1937 film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs[29]and later MGM’s 1939 The Wizard of Oz,[30] both of which received widespread praise for their effective and creative use of the technology. In a Seattle Times article covering the production of the film, a caption below a picture of two men by a camera reads: “Big money is represented by this big camera, one of eleven of its kind in the world. The Technicolor camera alone is valued at $16,000, and, with complete equipment, $35,000.”[31] Interestingly, the Technicolor color director for the film, Natalie Kalmus, would go on to work on The Wizard of Oz, making Gods Country and the Woman a sort of proving ground for perfecting the colorizing process. However God’s Country and the Woman was a picture about logging and did not focus on the surreal, so production was less forgiving of overly saturated colors and unrealistic footage.

Filming in Washington’s forests would prove to be a hit at the box office, but on location certain technical obstacles had to be overcome to make the film. The director of God’s Country and the Woman was interviewed by the Los Angeles Times in 1938 about the use of color in Hollywood films. “When we shot ‘God’s Country and the Woman […] we stayed on the edge of the forest, afraid to penetrate its depths for fear there would not be enough light.” He goes on to say that since the production of that film he his crew had become more confident in using the technology.[32] This confirms the notion that the movie was a sort of proving ground for the camera technology, showing that Washington’s forests could be used not only for their scenic beauty but also their technical challenges.

By the time the film went to theaters, it was clear that Technicolor shots of Washington’s made Hollywood’s use of the region a critical success. One Los Angeles Times review stated: “God’s Country and the Woman would be classed simply as a good outdoor picture, were it not for the experimentation of color. That is what gives the film life.”[33] Here the critic gives credit to Washington’s beautiful natural scenery coupled with color film. In addition to showcasing Washington in vivid color, the film also included real loggers from Crown Willamette Logging Company and received an entire page in the Seattle Times detailing its production.[34] The tone of the article is grateful of the individual stars’ presence in the state and explains their mannerisms on the set. The public was still very much infatuated with the stars, thought it seems that because the film was shot deep in forested areas of Washington away from the public that Hollywood benefited the most from the film.

Seattle's beautiful setting -- shown here in 1929 with Mt. Rainier in the background -- made it a popular choice for Hollywood directors, who chose its mountains as stand-ins for the Alaskan Yukon and filmed its waterfront for display in the new medium of film. Rainier was chosen by Hollywood as the site of the 1937 film Thin Ice, which brought celebrity figure skater Sonja Henie to Washington State. (Photo by M.P. Anderson, courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry)

The next film, Thin Ice, was filmed at Mt. Rainier for the same reason producers of The Call of the Wild chose to film elsewhere—there were plenty of skiers. Allegedly taking place at a Swiss ski hotel rather than the desolate Alaskan Yukon, the movie would actually benefit from the occasional skier passing in the background of the actors. However, shooting the film at Mt. Rainier was sometimes seen quite differently from the public’s perspective. A man interviewed by the Seattle Times in 1937 explained the antics of the Hollywood film crew that had spent $1,000 on a special prop only to realize it would be covered with snow: “They decided it looked better with snow on it so there is all that money and effort wasted.”[35]

While the film crew’s seemingly decadent spending on the arts during America’s greatest economic crisis seemed odd or trivial to some commentators, Hollywood’s expenses on production also translated to real economic benefits for locals. The Seattle Times reported that the baggage carriers at Paradise Lodge on Mt. Rainier were quite delighted to be given the chance to assist the leading lady and glamorous figure skater Sonja Henie. Additionally, the article notes that “Two dozen husky lads from the College of Puget Sound, hired as the company arrived in Tacoma from Hollywood yesterday, got behind schedule as they hauled tons of properties across the snow banks from trucks.”[36] Just as the Mt. Baker lodge had benefited from 20th Century Pictures’ expensive stay, Paradise Lodge at Mt. Rainier and college students from around the area were blessed with employment—and a touch of glamour— from the Hollywood visit. While the Hollywood studios brought much of their equipment and personnel from California, it seems that certain amenities and labor was simply cheaper or had to be acquired in Washington.

Paramount Pictures’ followed in the footsteps of The Call of the Wild with their own release, The Barrier, also filmed at the Mt. Baker Lodge and depicting scenes of the Alaskan Yukon. But why were neither of the films simply shot in Alaska? Two Los Angeles Times articles from 1932 may reveal that filming in Alaska at the time was too difficult of a task for a large Hollywood film crew to tackle. A May 1932 article describes film director W.S. Van Dyke en route to an Alaskan expedition to film Eskimos. Speaking of the difficulty in filming with arctic weathers the article states: “These expeditions are, therefore, fruitful, and Van Dyke is one of the few men in pictures who has manifested the requisite generalship to cause them to be successful.”[37] Another article from February 1932 spoke of Bernard R. Hubbard’s stop in Seattle to stage for his Alaskan expedition where he would film footage for the Pacific Geographic Society.[38] Each of the articles has the explicit use of “expedition” which likely indicates the expensive and harsh nature of Alaskan territory, and that it was unfit for the likes of movie stars and Hollywood crew who had box office revenue in mind.

However, the neglect of Alaska was to the benefit of Washington, and Mt. Baker in particular, as it would again enjoy the economic stimulus and free advertisement of having Hollywood stars and a production team in the area. A Seattle Times article detailed the expenses for filming in the remote location stating, “It costs about $38,000 just to feed, sleep, and transport the actors, directors, cameramen, electricians, technicians, script girls, ‘grips’ and the rest of the crew.”[39] The funding spent on food, lodging, and transportation among other things would be injected into Mt. Bakers’ surrounding economy. Soon, even the government got involved in making sure the film would support locals. According to the same article, the governor of Washington worked a deal with the director of The Barrier in which unemployed Washingtonians would work as extras in the mob scenes, making $60/week.[40] In addition to the money paid out to the Mt. Baker lodge and unemployed people of the state, the article mentions that an Alaskan village was constructed on the site where “half of the men came from Hollywood, half Mount Baker. They are paid $90 a week for their carpentry.”[41] It seems from this article that the film was beneficial to both Hollywood, in acquiring an authentic-looking set location and labor on the cheap, and to Washington, who gained an economic boost and free publicity.

A year before the production of The Barrier Mt. Baker outdoor recreational enthusiasts ran into their own barrier with the Forest Service when they pushed for ski lifts to be installed and explicitly referenced the previous filming in the region. A Seattle Times article from 1937 captured the sentiments of Mt. Baker skiers, who argued, “If an escalator or ski lift mars the natural beauty of the landscape, what will a replica of an Alaskan village do to it?”[42] Local residents were denied their addition to Mt. Baker, yet a California film studio seems to have come in without contention, showing just how influential Hollywood had become into the late 1930s in the state. While the governor had successfully negotiated work for the unemployed, it seems that politicians’ interests in filming in their state went beyond political duties. A 1937 article from the Spokesman Review claims that the governor simply wanted to meet the leading actress Jean Parker and appear as an extra in the movie, as he went into a lake “wading in with his whole summer outfit on, pulled her out of the water and kissed her.”[43] Clearly both politicians and the general public were fascinated with the movie stars.

The last of the major Hollywood studio films in Washington came from MGM in 1940 and included Seattle: Gateway to the Northwest and Glimpses of Washington State. These two films were short documentary-style productions featuring various locations of Washington from Eastern Washington to Seattle and received very little critical acclaim. In fact, their only appearance in Washington newspapers was as a show time listing. Truly, the last great influential films of the big Hollywood studios in Washington were those of 1937 that drew the attention of the public during production and were viewed across the nation. Nonetheless, the two MGM documentaries had their focus on the natural scenic beauty of the state.

Overall, the most influential Hollywood movies for Washington residents were those in which the government got involved, such as with plowing the roads for The Call of the Wild and organizing the unemployed to play extras in The Barrier. In these cases there was a direct influence on the state’s economy during production. Surely, Hollywood also benefited from Washington and effectively used the natural scenic beauty of the state as shown in the critics’ reviews. And despite Hollywood’s portrayal of Washington as a rural frontier or uncultured, non-urban region, in some films, the benefits to Washingtonians seemed to outweigh this potentially negative depiction of their state. The Golden Era of Hollywood, it seemed, relied for some of its successes on the Evergreen State.

Washington State Filmography

Primary Films

Title |

Director |

Year |

Production company |

Believe it or Not |

|

1932 |

WB |

Tugboat Annie |

Mervyn LeRoy |

1933 |

MGM |

Here Comes the Navy |

Lloyd Bacon |

1934 |

WB |

The Call of the Wild |

William A. Wellman |

1935 |

FOX |

Ruggles of Red Gap |

Leo McCarey |

1935 |

PAR |

Can You Imagine |

|

1936 |

Vitaphone |

God's Country and the Woman |

William Keighley |

1937 |

WB |

The Barrier |

Lesley Selander |

1937 |

PAR |

Thin Ice |

Sidney Lanfield |

1937 |

FOX |

Seattle: Gateway to the Northwest |

|

1940 |

MGM |

Glimpses of Washington State |

James A. FitzPatrick |

1940 |

MGM |

Secondary Films

Title |

Director |

Year |

Production company |

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs |

David Hand |

1937 |

DIS |

The Wizard of Oz |

Victor Fleming |

1939 |

MGM |

Copyright (c) 2010, Zachary Keeler

HSTAA 105 Winter 2010

[1] Colin Shindler, Hollywood in Crisis: Cinema and American Society 1929-1939, (New York: Routledge, 1996), pg 3.

[2] Shindler, pg 3.

[3] Shindler, pg 3-8.

[4] The Internet Movie Database. February 2010. Internet Movie Database Ltd. 2 February 2010 <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1064930/>.

[5] “Evangel Temple (Assembly of God).” The Seattle Times, May 15, 1954.

[6] “Marie Dressler Inspires Raine, Sea-Tale Author.” The Seattle Times, August 21, 1932.

[7] Lee Shippey. "The LEE SIDE o' L.A.: Personal Glimpses of Famous Folks." Los Angeles Times, December 11, 1932.

[8] "In Hollywood," Los Angeles Times, June 11, 1933.

[9] “‘Tugboat Annie’ Holds Interest of Seattleites.” The Seattle Times, July 30, 1933.

[10] “Welcome Flags Going Up for Annie’s Son.” The Seattle Times, April 19, 1933.

[11] “Seattle Will get Two Big Events in Entertainment.” The Seattle Times, July 16, 1933.

[12] “Cagney Injured while Making Navy Thriller.” The Seattle Times, August 4, 1934.

[13] Philip K. Scheur, "Guns, Milk Ingredients of Thriller: Grim Climax Marks Close of Newest Cagney Comedy." Los Angeles Times, November 23, 1934.

[14] "Along El Camino Real With Ed-Ainsworth." Los Angeles Times, March 23, 1935.

[15] Philip K. Scheur, “News and Gossip of Stage and Screen: A Town Called Hollywood,” Los Angeles Times (1934, September 2), p. A3.

[16] “Mount Baker Gale Defied Film ‘Call of the Wild’.” The Seattle Times, January 3, 1935.

[17] “Even Mt. Baker Blizzard Can’t Stop Cameras.” The Seattle Times, January 21, 1935.

[18] “Mount Baker Gale Defied Film ‘Call of the Wild’.” The Seattle Times, January 3, 1935.

[19] Jeff Jewell, e-mail message from author to the Whatcom County Museum, February 16, 2010.

[20] Edwin Schallert, "Griffith Casts Emlyn Williams, Footlight Star, as "Broken Blossoms" Lead: Actor Noted for His American Stage Work” and “Exodus to Broadway Starts With Many Stars Slated for Plays; Sally Blane Gets Lead in Harold Lloyd's Film, "Milky Way"," Los Angeles Times July 23, 1935.

[21] “Auto Caravan Bucks Blizzard to Mount Baker.” The Seattle Times January 27, 1935.

[22] "New Picture Announced: "Call of the Wild" to Open Wednesday." Los Angeles Times July 22, 1935.

[23] “Company Coming! Cinema Stars on Way to Seattle.” The Seattle Times, January 14, 1935.

[24] ""Call of Wild" Breaks Records." Los Angeles Times, July 26, 1935.

[25] Shindler, pg 144-60.

[26] "Showmen Try to Analyze Success of Gable Picture." Los Angeles Times, July 30, 1935.

[27] "Showmen Try to Analyze Success of Gable Picture." Los Angeles Times.

[28] Richard E. Hays. “Fine Comedy, ‘Ruggles,’ Arrives.” The Seattle Times, January 14, 1935.

[29] The Internet Movie Database. February 2010. Internet Movie Database Ltd. 2 February 2010 <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0029583/>.

[30] The Internet Movie Database. February 2010. Internet Movie Database Ltd. 2 February 2010 <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0032138/>.

[31] Richard Heilman. “Movie Stars Are Just Folks As They Film “God’s Country’.” The Seattle Times, July 26, 1935.

[32] Kay Campbell, "Film Information News of Stage and Screen, New Offerings: Hollywood Advances Color Films." Los Angeles Times, July 17, 1938.

[33] Edwin Schallert, "Color Aids Outdoor Film Play." Los Angeles Times,February 12, 1937.

[34] Richard Heilman. “Movie Stars Are Just Folks As They Film “God’s Country’.” The Seattle Times, July 26, 1935.

[35] “The Timer Hs the Last Word.” The Seattle Times (1900-1971) April 27, 1937.

[36] “Sonja, Tyrone Holding Hands.” The Seattle Times (1900-1971) April 2, 1937.

[37] Edwin Schallert, "Expedition to Get Under Way: Eskimo Director, Author Leaving for Far North” and “Horizon of Screen Extended by "Two Seconds" Fantastic Films Successful if Given Chance," Los Angeles Times, May 27, 1932.

[38] "Alaska Thrills to Be Shown by Father Hubbard." Los Angeles Times, February 27, 1932.

[39] “Players Really ‘Rough It’ In Making of ‘The Barrier’,” The Seattle Times,July 18, 1937.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] “THE TIMER….. Has the Last Word.” The Seattle Times June 4, 1937.

[43] “Martin kisses film actress.” Spokane Review (1889-1950), July 26, 1937.