by Claire Palay

Art professor Lea van Puymbroeck Miller was dismissed in 1938 in violation of the University of Washington's "anti-nepotism" laws, which denied married women their own jobs. National and local employment policies during the Great Depression favored male heads of households, and privileged men's jobs over women's. Miller fought her dismissal but was ultimately unsuccessful. This image is from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, January 3, 1938. Click on the image to enlarge.

As the Great Depression sent waves of unemployment throughout the country, the role of women in the workforce came under intense scrutiny. The confusion and anger produced by the sudden economic downturn left the nation looking for somebody to blame. Working wives, perceived to be working for pin money while men struggled to find work to support their families, became the target of public animosity. To many, the notion that some families could be privileged with two incomes seemed unjust in such a trying economic time. This concern over dual income families in Washington State led the University of Washington to quietly pass an “anti-nepotism” resolution in 1936, banning the University employment of more than one member of any household. The firing of respected art instructor Lea Puymbroeck Miller under this policy quickly brought national attention to the initially unnoticed resolution. The Miller case became the center of a raging debate over the right of women to work and the security of academic tenure at the University.

The structure of the female labor force underwent significant changes between 1890 and 1930 as women began to pursue professions outside industrial and domestic work. The founding of new professions such as social work, librarianship, and nursing, along with the feminization of the teaching and clerical fields brought more women, especially educated women, into the non-industrial, non-domestic workforce.[1] As these opportunities expanded, more women demanded that they be allowed to continue their work after marriage. [2] In the 1920s married women entered the workforce at an extraordinary rate.[3] However, the progress of the 1920s was brought to a halt as the pressures of the Great Depression forced women out of the workforce. Women who had enjoyed the newfound freedom to work were suddenly forced to defend their right to a job.[4] In King County a resolution was introduced which banned the county employment of all married women who were not the sole providers for their families. These positions were to be filled by men with families. Oddly enough, many of the married women affected by the resolution were the married nurses at Harborview Hospital.[5] The firing of these married women from an all-female profession demonstrated how severe and illogical the opposition to working wives had become.

At the University of Washington, the administration became extremely concerned with the small group of married women on the faculty. In 1933 the University comptroller compiled a list of all female employees with gainfully employed husbands, not just those married to other University employees. In the 1933–1934 budget, the University administration went so far as to recommend that “those married women who were on the payroll whose husbands are able to support them” be dismissed from their positions. While this recommendation was not enacted, the University continued to compile lists of “Married Women and Relatives” and “Married Couples.” In 1935, Governor Clarence Martin pressured the recently appointed President Lee Paul Sieg and the University Regents to investigate the question of nepotism on the University faculty. Using the information from the compiled lists, Sieg and the Regents began to move quickly on an anti-nepotism resolution.[6]

The University of Washington’s “anti-nepotism” resolution was adopted by the Board of Regents in January of 1936. Designed to solve the financial woes of the Depression, the resolution sought to eliminate “dual family” employment at the University: "In the future husband and wife shall not both be employed by the University if either one occupies a regular full time position on the academic teaching staff above the rank of assistant."[7]

The resolution was declared non-retroactive so as not to “embarrass” any already married staff members. This decision protected the positions of four married couples on the faculty, temporarily avoiding staff uproar over the resolution. Eager to keep the new policy as quiet as possible, President Sieg limited news of the resolution to department chairmen who were instructed to quietly inform the rest of the staff. [8]

When Lea von Puymbroeck married her colleague, Prof. Robert Miller, a zoology professor at the University of Washington, she lost her own position on the faculty. This image and description is from the 1937 Tyee yearbook (p. 97), before the Millers were married. (Courtesy of University of Washington Library, Special Collections)

The anti-nepotism policy remained a University secret until the highly publicized firing of Lea Puymbroeck Miller in December of 1937. Miller, an instructor of design in the Fine Arts Department had been a member of the University faculty since 1930 and even received a promotion in 1934. Miller had spent the previous fifteen months away from the University doing special study abroad. Unaware of the 1936 resolution, she had recently married Robert Miller a professor in the Zoology department. Upon her return to the University in the fall of 1937, Miller was informed by her department head that, due to her recent marriage, she was to be dismissed from the University. Miller was confused by the news of her dismissal; she had not received any official statement from the Board of Regents regarding any contract violations, nor had she received formal notice that her contract had been revoked. To be dismissed so suddenly and informally, Miller felt, was a clear violation of her academic tenure.[9]

In a letter to President Sieg dated December 20, 1937, Miller requested that her case be reconsidered. She emphasized that she had been uninformed of the University’s dual family employment policy:

"The resolution which has been invoked as a basis for my dismissal was never known, nor quoted to me prior to my marriage nor—for that matter—has it been since. There is nothing in the wording of a University appointment to indicate that they are contingent on the celibate state. "

Besides being unaware of the policy, Miller stressed that due to the University’s lack of a sabbatical fund she had forfeited her salary for the last year in order to improve herself and her work. She argued that her completion of such extra study should increase her value and result in her promotion, not dismissal. Finally, Miller challenged the Regents’ authority to fire her midway through her contract year, and asserted that news of her dismissal would provoke uncertainty and anger from her colleagues.[10]

The administration’s treatment of Miller did indeed provoke great alarm from the rest of the faculty. These concerns were voiced by the Instructors’ Association, which represented a large portion of the University faculty, including Miller. The Instructors’ Association remained supportive of the University’s decision not to hire any new faculty members with relatives already employed by the University. However, they felt that the Regents were applying the rule retroactively to the Millers. Considering that both the Millers had been employed, though not yet married, at the time of the resolution’s passing, the association petitioned the Regents to reconsider.[11] This argument was disregarded by the Regents who stated that the decision to not apply the resolution retroactively had been made only to protect the marriages already in existence at the resolution’s adoption. In a letter to the Instructors’ Association dated December 7, 1937, the Regents expressed concern that to allow such an exception would open the door for too many potential cases in the future:

The UW Board of Regents in 1949. President Sieg, who oversaw Miller's firing, is to the left, second step up, in glasses and a hat. Click image to enlarge. (Photo by Cliff McNair, courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collections)

"The Board’s previous assurance that the rule would not be applied retroactively of course was prompted by the desire not to embarrass any marriage existing at the time of the rule. The Board further feels that to recognize this type of case as involving the element of “retroaction” would effectively nullify the rule in a large number of cases and would to that extend tie the hands of the administration for all time."[12]

The Regents’ unwillingness to recognize the application of the resolution to the Millers as retroactive blocked one of the most compelling arguments for the case’s reconsideration.

Lea Miller did not simply leave her defense to the Instructors’ Association; she continued to speak out on her own behalf. She pointed out that her treatment was completely out of line with the dismissal procedures laid out by the American Association of University Professors, which stated that:

"The terms of all appointments should be in writing….Except in cases of extreme aggravation, or where the facts are admitted, permanent or long term appointments should not be ended without faculty consultation and action by the governing board. Except in extreme cases, dismissals should only be after a year’s notice."[13]

Miller held an annual contract with the University and had fulfilled all her duties for the fall term. She was then suddenly and unceremoniously informed of her dismissal by her department head, only after her replacement had been found. Miller had received no formal written notice as required by the above requirements, nor was she given the benefits of faculty consideration or proper notice. The conduct of the University administration demonstrated a distinct lack of respect for Miller as a person and as an established faculty member.

This obvious mistreatment of Miller and the violation of her contract became another focus of the Instructors’ Association. Although it sought to eventually overturn Miller’s release entirely, the Instructors’ Association petitioned President Sieg on January 4, 1938 to permit Miller to finish out her contract, "Mrs. Miller should be dismissed, if at all, only at the end of the present academic year. We can see no basis for terminating her appointment at the end of the fall term, and we feel it would be in accordance with good academic procedure in case of dismissal to permit her to serve out the remainder of the year covered by her present agreement with the administration."[14]

The Instructors’ Association proceeded to remind President Sieg of a previous agreement he had made in 1934, which promised that a faculty committee would be appointed to consider any matter of faculty dismissal. To dismiss Miller without any faculty involvement was clear reversal of this agreement.

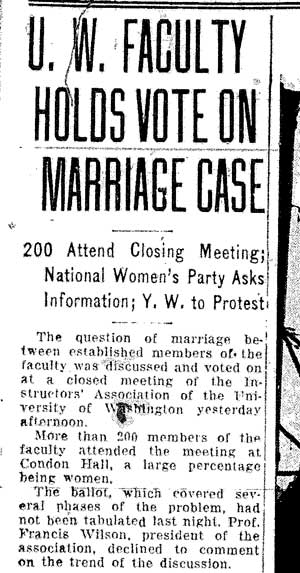

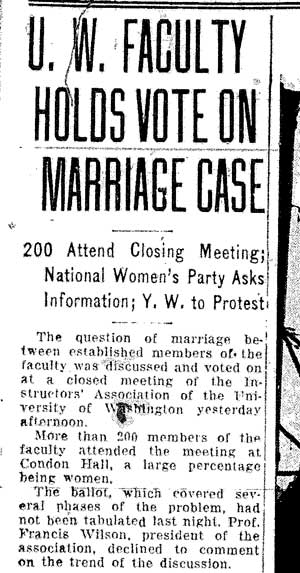

An article from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer from January 14, 1938, reporting on a mass faculty meeting to discuss the anti-nepotism policy. Note that the article states a large proportion of those attending were women, signifying how important Miller's case was to female faculty. Click the image to read the full article.

The Instructors’ Association polled the faculty on Miller’s release. On January 14, 1938 the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that over two hundred faculty members had gathered at Condon Hall to discuss the questions of marriage and dismissal policies at the University.[15] Voting on four specific issues the faculty decisively supported the reversal of Miller’s case and opposed the firing of established faculty based on marital status. Additionally, almost all polled demanded that faculty be included in deliberations in any case of dismissal and restated the requirement of a year’s advance notice before any dismissal.

Despite the best efforts of Miller and the Instructors’ Association, the UW Board of Regents voted unanimously to reaffirm both the anti-nepotism policy and Miller’s dismissal. The letter confirming this decision from President Sieg to Miller exemplified the perfunctory attitude the Regents has assumed throughout the controversy:

"May I inform you that the Board of Regents on January 15, 1938 confirmed your withdrawal from the University faculty, effective January 1, 1938. The Board expressed its appreciation of your excellent past service."[16]

Clearly frustrated by her treatment, Miller informed reporters that the Regents’ ruling demonstrated that, “University appointments have no legal status and exist only as gentlemen’s agreements.” [17] However Miller and the Instructors’ Association accepted the ruling as final. The Millers moved to California to continue their careers at the University of California at Berkley soon after. While the controversy may have been over for the Millers, the raging debate of public opinion continued.

Those following Miller’s case were divided in their reactions. Generally those who responded to the case were less interested in the details of academic tenure and more concerned with the larger issue of working wives. Those supporting Miller’s dismissal expressed opposition to the notion of dual-income families and sympathized with the plight of unemployed men. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer published a letter expressing the frustrations of the many unemployed men: "Were she a man and less fortunately situated she would no doubt realize just what it would mean when attempting to secure a position to find so many of them filled by women whose husbands were also gainfully employed."[18]

This view was shared by the many others, including the Seattle Central Labor Council. Although generally a progressive organization, the council’s Executive Board supported Miller’s dismissal, affirming that the wives of union workers should be discouraged from working except in cases when a husband was unable to work.[19] This sentiment reflected the societal norms of the time. Many were more interested in the potential positive effects for men in the job market than the policy’s negative implications for women. [20]

Those who opposed the UW Regents offered several arguments against Miller’s dismissal. Many saw the controversy as a fight for women’s rights to a career and to happiness. Advocates of women’s rights pointed to the overtly discriminatory nature of a policy that placed more importance on a woman’s marital status than her teaching ability. This inequity in the treatment between married men and married women was highlighted by Anna Thomsen Milburn, Washington State chairman of the National Women’s Party in a 1938 article in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer: "Back of a man stands always the constitution of the United States protecting him in his right to the ‘pursuit of life liberty and happiness.’ Back of a woman still stands (except in her right to vote) the old common law of Blackstone which said ‘when a man and woman marry they become one and that one is man.’"[21]

Milburn emphasized that a woman is also a person, and should be given the same legal rights as a man. She argued that many “enlightened” men and women would share her anger when they discovered the “hundreds of discriminations which still exist in our country.”

Besides protesting the discriminatory aspects of the policy, some questioned the logic upon which the policy was based. The Board of Regents received a letter from the Washington Educational Employees Union Local 483, suggesting that the policy was based on “fallacious assumptions.” The WEEU argued that the University had overlooked the true reasons for the lack of available jobs, asserting that through the anti-nepotism policy the Regents sought to simplify the complex situation at the expense of married women. The group also suggested that if faculty positions were to be terminated on the basis of economic need and not teaching ability, instructors receiving money from investments or inheritances should also be dismissed.[22]

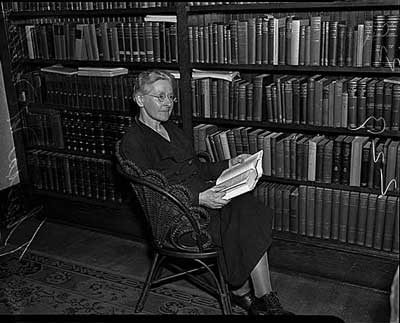

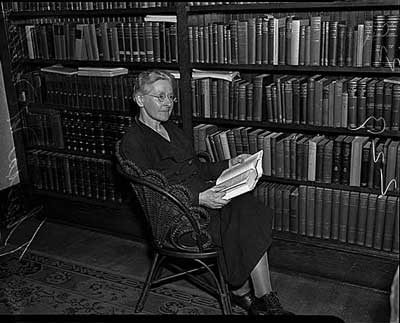

Dr. Theresa McMahon, shown here in Seattle in 1938, argued against gender-based discrimination at the University of Washington, where she had been a professor of economics. The same anti-nepotism policies that led to Lea Miller's firing led the University Administration to encourage McMahon to retire. Click image to enlarge. (Courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry)

Additionally, some questioned the effect of a non merit-based employment system on the faculty of the University. On January 7,1938 the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported on the reaction of Dr. Theresa McMahon, former professor of economics at the University. McMahon recounted her own experiences of sexual discrimination at the University of Washington and expressed her belief that sexual discrimination at the school would eventually make the University an institution of political patronage.[23] This concern was also expressed by Prof. Grace De Laguna, a visiting professor from Bryn Mawr College, who remarked that she had never heard of the same policy at any other college or university. In an interview with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, De Laguna commented on the terrible loss of academic talent that would result from such policies: “If this ruling were universal some of the world’s greatest teachers would have to leave their present positions.”[24] Critics of this policy such as McMahon and De Laguna wondered openly how a university could maintain a professional reputation with such biased hiring practices.

Over time, memory of the Miller controversy faded. President Sieg continued to enforce the anti-nepotism policy with little resistance. Several other women instructors were dismissed after marrying other members of the faculty, but unlike Miller they raised little controversy over the issue. In 1944 President Sieg attempted to make the policy retroactive, but the powerful opposition of the Instructors’ Association forced Sieg to revert to the original 1936 policy. This regressive policy remained in effect until 1971. The longevity of the policy, which failed to alleviate any of the economic problems it aimed to address, demonstrated the difficulties faced by many working women of the time. Even a supposedly enlightened institution such as the University of Washington felt comfortable with an overtly discriminatory policy which served no other purpose than to prevent many educated women from reaching their full potential.

See part 2 of this series on Lea Miller and working women, Married Women's Right to Work: "Anti-Nepotism"Policies at the University of Washington in the Depression, by Katharine Edwards

Copyright (c) 2009, Claire Palay

HSTAA 105 Winter 2010

[1] Sharf, Lois,

To Work and To Wed

: Female Employment, Feminism, and the Great Depression (Westport Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1980), p. 5.

[2] Sharf, Lois,

To Work and To Wed p 23.

[3] Hall, Margaret, “A History of Women Faculty at the University of Washington” p. 219 unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of Washington, 1984, pp 221-224.

[4] Hall, Margaret, “A History of Women Faculty at the University of Washington” p. 219

[5] Berner, Richard,

Seattle 1921-1940: From Boom to Bust (Seattle: Charles Press, 1992) pg 285.

[6] Hall, Margaret, “A History of Women Faculty at the University of Washington” unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of Washington, 1984, pp 221-224.

[7]UW Board of Regents Records, January 31, 1936, 81 – 01, Box 31-16, University Archives, UW Libraries.

[8] Hall, “A History of Women Faculty at the University of Washington, p 216 – 217,

[9] Lea Miller, letter to Lee Paul Sieg, December 20, 1937, UW President’s Records, Accession 71 – 34, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 113 folder 15.

[10] Lea Miller, letter to Lee Paul Sieg, December 20, 1937, UW President’s Records, Accession 71 – 34, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 113 folder 15.

[11] Hall, “A History of Women Faculty at the University of Washington, p. 228.

[12] Herbert Condon, Secretary, UW Board of Regents letter to Francis Wilson, Chairman Board of Instructors Association, December 7, 1937 UW President’s Records 71-34, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 113 folder 15.

[13] Hall, Margaret, “A History of Female Faculty at the University of Washington” p 238.

[14] Francis Wilson, Chairman, Instructors Association letter to LP Seig, January 4, 1938, UW President’s Records, 71-34, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, Box 113, Folder 15.

[15] “UW Faculty Holds Vote on Marriage Case”

Seattle Post Intelligencer, January 14, 1938, p.3.

[16] L.P Sieg, letter to Lea Miller, January 15, 1938, UW President Records, 71-34, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 113, Folder 15.

[17] “UW Regents Uphold Ouster of Mrs Miller”,

The Seattle Post Intelligencer, January 16, 1938.

[18] Letter to the

Seattle Post Intelligencer, “Working Wives”, January 8, 1938.

[19] “Unions Oppose Working Wives,”

The Seattle Times, January 12, 1938, p.9.

[20] Hall, Margaret, “A History of Women Faculty at the University of Washington” pg 236.

[21] “Woman Leader Attacks Ban on ‘Working Wife,’’

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, January 5, 1938, p. 1.

[22] The Washington Educational Employees’ Union Local 483, letter to University of Washington Board of Regents, January 11, 1938, UW Board of Regents Records, 78-103, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 31 folder 16.

[23] “Ex-Instructor Hurls Unfair Charge at U.,”

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, January 7, 1938, p.3.

[24] “Eastern Teacher Scores U. Ouster,”

The Seattle Post Intelligencer, January 10, 1938, p.3.