Depression-Era Civil Rights on Trial: The Battle of Congdon Orchards in the Yakima Valley

by Mike DiBernardo

Hop Field Workers, ca. 1930s. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

During times of crisis, civil rights are defined and realized; the future of civil rights is set in motion. In 1933—the height of the Great Depression—labor unrest occurred throughout the Pacific Northwest. As in the rest of the region, the desperation of laborers and the inability of employers to meet the basic needs of working people fueled the strikes and riots in the orchards and hop farms in Washington’s Yakima Valley. In and around the city of Yakima, conflicts between farmers and strikers developed into brutal riots. One of these conflicts occurred on August 24, 1933 at the Congdon Ranch, where 250 farmers, acting as a militia, confronted a much about 100 striking workers and members of the radical union formation the Industrial Workers of the World. The labor agitators were arrested and placed in jail, and many of were indicted for first-degree assault.[1]

Rather than attempt to prove the guilt or innocence of a particular party, the events at the Congdon Ranch, and the legal proceedings that followed should be used to illustrate issues of social and civil rights in the United States at the height of the Great Depression. The events in Yakima illustrated the particular political climate in Yakima Valley, particularly regarding freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and the basic rights of workers—the right to a living wage, the right to organize a union, the right to strike. In examining the legal proceedings following the “battle of Congdon Orchards,” we can tell that the Yakima Valley in 1933 was hostile to workers’ strikes and organization, and that the right to a living wage was not seen as justification for stopping work. Though the formal case tried picketing workers for the assault on one farmer, the implications were much broader, and debated the civil rights of workers and labor organizers as well as what constituted lawful governmental repression.

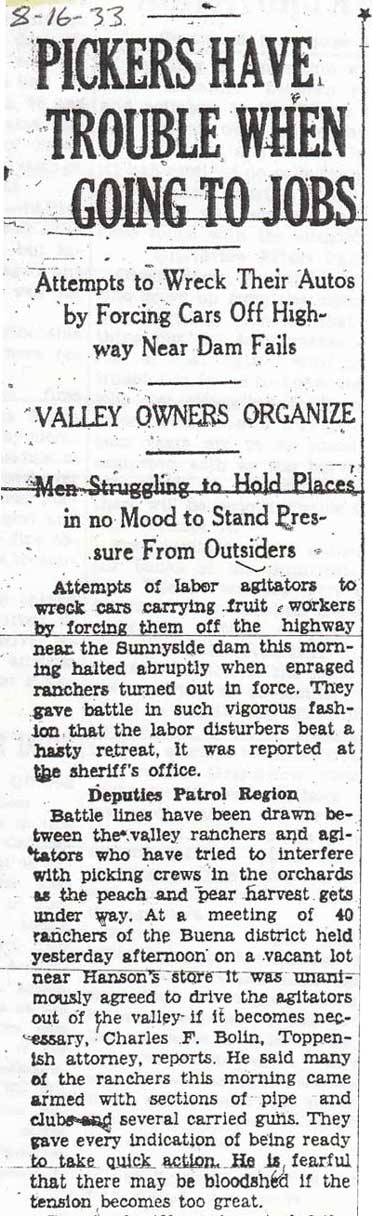

Farmer owners met and agreed to drive the "agitators" out of theYakima Valley, "if necessary." From the Yakima Daily Register, August 16, 1933.

As early as the 1910s, the radical labor organization the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or “Wobblies”) was attempting to organizing farm workers in the fertile orchards and hop fields of Yakima Valley in central Washington State. The IWW believed that all workers had the right to organize a union, receive decent wages, and have a voice in their work situation, and ultimately hoped that workers would combine into “one big union” with enough power to determine their own future independent of the employers. The IWW campaign was met with resistance and hostility from local and state police as well as farmers, and these decades of hostility toward labor radicals set the stage for the battle at Congdon Ranch. Despite this, though, the picketers and defendants were able to frame their arrests as violations of basic civil liberties, a huge legal success under the circumstances.[2]

Despite conflicting reports of the events at the Congdon Ranch, we can be sure that the strike was rooted in the need for increased wages for harvesters and processors. In a letter to historian James Newbill written decades after the Yakima strikes, Fred Thompson, an IWW leader, reflects on the issue of wages at the time of the strikes: “in the hop strike...wages rose from 10 cents [an hour] for men and 8 cents for women to 12.5 cents for both.” Thompson goes on to assume that a laborer would need 90 cents per day for “basic sustenance”: even a seemingly small increase in wages can offer a worker something beyond a day-to-day struggle for survival; workers can have money for what Thompson calls “life and living.”[3] An identical issue fueled the orchard strikes, including the conflict at Congdon Ranch.

Small farmers felt themselves victims of the Depression, and claimed their own poverty as reason for not being able to pay workers more. Elizabeth Bannister, the daughter of a farmer involved in the Congdon riot, could not ignore the terrible specter of poverty haunting the Yakima Valley. In an interview with James Newbill, Bannister remembers her father being “terribly caught up in the fact that this was the depths of the Depression and [someone] was going to have to harvest the crop.” Moreover, regarding her father’s loans to finance the farm, Bannister recalls, “there were all these worries about who was going to foreclose on what.”[4] In a time of desperation and uncertainty, on the edge of failure themselves, farmers were unwilling to pay their employees anything more than the bare minimum.

On the other hand, labor activists, particularly the radical Industrial Workers of the World, argued that a living wage was a basic human right, one that merited civil disobedience or violence if it was ignored. In a collective affidavit issued after being charged for the first degree assault of a farmer named J.C. Young, defendants in the case—many of whom were affiliated with the IWW—understood actions taken by police and vigilante farmers as a preemptive attack on peaceful demonstrators. Also in this affidavit, we see that the IWW agitated for higher wages for workers, many of whom chose to strike alongside the Wobblies. Only a “sprinkling of farm workers who have accepted un-American low standards of living” chose to follow the vigilante farmers into battle with picketers.[5] The defendants based their claim to justice on the fundamental rights of the working person: a decent wage and a decent life. Anything less was barbaric, and a mockery of the American ideal.

This stockade was built built within 24 hours specifically for the prisoners of the battle at Congdon Orchards, August 10, 1939. (Courtesy Library of Congress).

As implied by the basic demands of the picketers and the situation of the farm owners, we can see that low wages were socially acceptable. From the picketers’ continued testimony, we can also see that the right to organize a union and strike were constantly embattled, particularly as union organizing wouldn’t become a federally recognized legal right until 1935. Again, in their court affidavit, defendants in the J.C. Young assault case claim that their peaceful picket at the Congdon Ranch was terrorized by a vigilante brigade of farmers “out-numbering [the picketers] five and six to one.” Moreover, this brigade was heavily armed with “gas-pipes, baseball-bats, pick-handles, pitch-forks, clubs and rocks,” and some of the farmers had the even greater advantage of being on “horse-back.” The defendants could not even find sanctuary on legally public land, and were pushed off the Congdon property to an area known as the “Triangle”—an area between the farms and a highway—and ultimately to the highway, where the farmers finally decided that the defendants “were on public property.” However, “immediately after” the picketers reached the highway, the farmers began their attack. The picketers were being punished for committing an original sin in the Yakima Valley: labor agitation.[6]

In the perspective of the defendants, Yakima, with its highly organized citizen militias, possessed a social climate that was hostile to the voice of labor. George F. McAulay, like many other individuals who testified against the defendants in the J.C. Young assault case, claimed that the farmers were victims who needed to protect themselves from labor agitations; as he said, “a number of… farmers [organized] themselves into some sort of a protective organization…solely for the purpose of protecting themselves, their property, and others working for them from injury and violence.”[7] McAulay denied claims of unwarranted abuses of strikers by the farmer’s militia. The swift and heavy-handed methods used by police and vigilantes and the outcry from the defendants as well as various other community members make clear that the case is about more than the assault on one farmer. Instead the case debated the rights of workers over farm owners, and ultimately, the right of either side to advance its interest was being decided.

Reports about the initiation of the battle make clear that the issue debated in the courtroom was about much more than the actual assault on J.C. Young, but was about whether or not workers were allowed to picket. “Labor trouble” brought the farmer militia to the Congdon Ranch.[8] “Labor trouble” meant the disruption of work and agitation by workers, and speaks to the lack of patience in the Yakima Valley for labor agitation. For example, Emory Hale, a local sheriff, remembers telling IWW protesters, “if you continue [agitating workers]… we’ll start picking you up for… interfering with people’s progress.”[9] And, according to Robert Blankenbaker, a worker who did not picket but was jailed in the battle’s aftermath, two sides—vigilante farmers and strikers—were at an impasse, each “arguing about the right of picketing.” Then, suddenly, as Blankenbaker remembers, “somebody said you dirty so-and-so…[and] somebody was his on top of the head…the fight was on.”[10] Clearly, it is difficult to find someone to blame for the actual initiation of the Congdon battle. However, we can see in Blankenbaker’s and the sheriff’s remarks that more than the identification of an individual, the issue at stake is the culpability of the striking workers, and whether they were justified in picketing.

It is impossible to simply regard the battle at the Congdon Ranch as a local issue, as police and National Guard troops, as well as vigilante farmers, unionists, and farm workers were involved. The involvement of state law enforcement officers raised another civil rights issue: the repression of the inalienable rights of individuals by governmental authorities. For instance, Robert Blankenbaker asserted that when police officers confronted strikers, “no arrests [were] made. Who could make a legal arrest?” Blankenbaker goes on to describe the poor conditions in the city jail, as well as his interrogation by police.[11] In Blankenbaker’s account, city police unlawfully corralled and jailed individuals innocent of the violence perpetrated at Congdon Ranch. What’s more, police acted on the side of the farmer militia, jailing the strikers who had already been corralled by mounted vigilantes without making arrests.

Possibly the most egregious violations of social, and potentially civil rights in the Congdon affair involved two men unaffiliated with the IWW or the labor movement: Mike Capelik and Casey M. Boskaljon. In similar testimonies, each man complained of being arrested for reasons unknown to them, detained, and finally released only to fall into the waiting hands of vigilantes who proceeded to torture them. Alleging collusion between police, governmental authorities, and the renegade vigilantes was at the heart of each man’s testimony. For instance, as Capelik tried to enter the jail to interview the defendants, a deputy jailed him without charging him with a crime. Capelik claimed that he was then interrogated by “an official who said that he represented the Agriculture and Immigration Department of the United States Government.” When the official recommended that Capelik be “turned loose,” Capelik was again interrogated by “two detectives, a Deputy Sheriff, and a High-way patrolman.” Finally the detectives and Deputy Sheriff led Capelik at gunpoint to a mob of vigilantes.[12]

Boskaljon’s account is no less disturbing than the testimony of Capelik. In his testimony, Boskaljon was simply plucked from the Yakima fairgrounds, a natural place to be for the Secretary of “an organization known as the United Farmers League”—a definitively non-radical organization—only to be “severely beaten by a State Patrolmen” and carried away to jail. Mysteriously, after several days in jail, Boskaljon was forced to leave, even though, frightened of the potential danger outside, he “[asked] the jailer to let [him] stay until morning.” Boskaljon was, of course, captured by vigilantes, driven miles away from the nearest town and beaten again, this time left for dead. Concluding his sworn testimony, Boskaljon claimed that he “had said nothing and had done nothing to be charged with a crime and certainly nothing that should have caused people to treat me in this manner.”[13]

In a letter to historian James Newbill, L.B. Vincent, a practicing attorney at the time of the Congdon riots, wrote: “I have no idea [what legal processes were used to hold the imprisoned workers]…what about their civil rights?”[14] The testimonies of Mike Capelik and Casey Boskaljon embody the concerns that Vincent expressed in regard to the horrible events in the Yakima Valley. The men, uninvolved with either side in the Congdon battle, gave convincing and damning accounts of the repressive tactics of local authorities. These accounts spurred a wave of support from labor leaders and forced other witnesses on the side of the farmers in the J.C. Young case to at least acknowledge the possibility that they had undermined the civil rights of innocent citizens. Certainly, the J.C. Young case went far beyond a singular and isolated incident involving the assault of an innocent farmer. The case highlighted the prime concerns of people in the Depression: the maintenance of civil rights during social crises and the freedom to enjoy the fair and ethical treatment of government authorities.

Ultimately, as events reached a fevered pitch, Washington State’s case against the IWW organizers was dismissed for logistical reasons: the city of Yakima did not wish to pay the cost of trying the defendants.[15] In a sense, the Congdon battle ended in a stalemate. Perhaps, however, the anti-climactic conclusion to this tumultuous story represents a turning point in American labor relations—a time when labor martyrs Sacco and Vanzetti and the Haymarket anarchists were becoming a tragic part of labor’s past, and the victories of the CIO labor’s triumphant future. In their waning years, the Industrial Workers of the World managed to force a dialogue around the civil rights of workers even in the hostile climate of the Yakima Valley.

Copyright (c) 2009, Mike DiBernardoHSTAA 353 Spring 2009

[1] Robert L. Tyler, Rebels of the Woods: the I.W.W. in the Pacific Northwest (Eugene: University of Oregon, 1967), pp. 222-224.

[2] Tyler, Rebels of the Woods; Oscar Castanedes and Maria Quintana, “Timeline: Farmworker Organizing in Washington State,” Farm Workers in Washington State History Project on the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project website, <http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/farmwk_timeline.htm>.

[3] Fred Thompson, letter to James G. Newbill, April 27, 1977, James G. Newbill Research Materials, Accession 5258-w1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 45.

[4] Elizabeth Bannister, interview with James G. Newbill, August 9, 1973, James G. Newbill Research Materials, Accession 5258-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 4.

[5] Collective affidavit of defendants for the State Washington vs. Frank Anderson, et. al case, October 6, 1933, Mark Litchman Papers, Accession 0165, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 3.

[6] Collective affidavit of defendants for the State Washington vs. Frank Anderson, et. al case, October 6, 1933, Mark Litchman Papers, Accession 0165, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 3.

[7] Affidavit of George F. McAuly for the State of Washington vs. Frank Anderson, et. al. case, October 18, 1933,

Mark Litchman Papers, Accession 0165-001, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 1.

[8] Elizabeth Bannister, interview with James G. Newbill, August 9, 1973, James G. Newbill Research Materials, Accession 5258-1, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 4.

[9] Emory Hale, interview with James G. Newbill, July 26, 1973, James G. Newbill Research Materials, Accession 5258, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 15.

[10] Robert Blankenbaker, interview with James G. Newbill, August 8, 1973, James G. Newbill Research Materials, Accession 5258, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 6.

[11] Robert Blankenbaker, interview with James G. Newbill, August 8, 1973, James G. Newbill Research Materials, Accession 5258, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 6.

[12] Affidavit of Mike Capelik for State of Washington vs. Frank Anderson, et. al. case, September 12, 1933, Mark Litchman Papers, Accession 0165, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 3.

[13] Affidavit of Casey M. Boskaljon for State of Washington vs. Frank Anderson, et. al. case, October 2, 1933, Mark Litchman Papers, Accession 0165, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 3.

[14] L.B. Vincent, letter to James G. Newbill, July 27, 1974, James G. Newbill Research Materials, Accession 5258-001, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 3, folder 49.

[15] Tyler, Rebels of the Woods, p. 225.