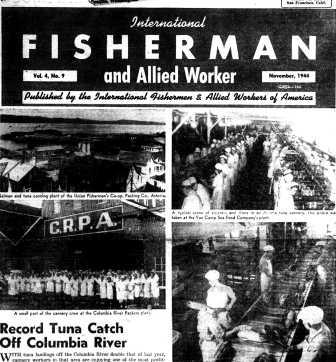

The commitment to increased production was evident in wartime issues of the union newspaper, as was the changing demography of the industry. Women handled more of the cannery jobs stateside while Alaskan Natives found work in the northern canneries.

International Fishermen and Allied Worker , November 1944.

This essay is presented in five chapters.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Early Unionism in the Pacific Coast Fisheries

Chapter 3: A Coastwise, Industrial Union

Chapter 4: World War II

Chapter 5: Struggle, Strikes and Collapse

Leo Baunach's essay won the 2013 Library Research Award given by University of Washington Libraries.

1944 Convention

1944 Convention

International Fishermen and Allied Worker , February 1944

by Leo Baunach

Even as the new industrial union of fishermen took shape, the world was turning towards war. Within months of IFAWA's founding, Europe was locked in combat with the United States to follow two years later. And long before Pearl Harbor war was reshaping the fishing industry and creating challenges and opportunities for the CIO's West Coast fishing union. Security concerns and manpower shortages would transform the demography of the union, creating opportunities for women and Native Alaskans. The union's ties to the Communist Party created other challenges, first during the period of the Hitler-Stalin pact, then again as anti-communism became a central theme of post-war America.

As we have seen, the union traced its origins to the efforts of the Communist Party, and CP members were influential at local and international levels. As with other Party-linked organizations, the global situation became a source of internal and external tension when in late 1939 the Party took the position that the United States should stay out of the war, end support for England and France, and reject the defense buildup ordered by the Roosevelt administration. The Party's antiwar position hurt its standing in the CIO and set off a wave of federal investigations and prosecutions. In unions like the United Autoworkers Workers and International Woodworkers of America fierce internal battles resulted in changes in leadership and political orientation.

Nothing similar happened in IFAWA. The union's Party connections led it to advocate for peace during the Hitler-Stalin pact that ended abruptly in June 1941 when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. However, the peace politics was limited to rhetoric and indeed even that was inconsistant. The largest IFAWA component, the United Fishermen’s Union, approved a resolution in December 1940 in which the membership pledged that they were “willing at any time to go the defense of their country” and volunteering time to act as a Naval auxiliary.[1] This was in part motivated by the union’s vehement animosity toward imperial Japan, which wedded practical concerns and anti-fascism. Opposition to imports of cheaper Japanese fish and the encroachment of Japanese boats into Alaskan and deep sea areas off the West Coast had long been a pillar of unity in IFAWA. [2] Just days before Pearl Harbor, the union’s Convention passed a resolution decrying the use of underpaid “slave” labor by Japanese fishing companies and stating that “several years ago our union warned of the invasion of our fishing grounds in the North Pacific by the Japanese fascists and lodged protest after protest with the State Department.”[3] This anger at foreign Japanese competition and a general failure to build relationships with significant numbers of Japanese-American fishermen, primarily in California, caused the union to be silent on internment. In its newspaper, the union coldly concluded that “since [Japanese fishermen] comprised less than 10 per cent of the total number of workers [in San Pedro], the industry will not suffer serious dislocation.”[4] However, evidence suggests that a fully quarter of fishermen in California, including Japanese and non-citizen European immigrants, were barred from working during the war.[5] It took two full years after the end of the war for IFAWA in the Puget Sound to officially resolve “that the Interned Japanese Fishermen who were members in good standing on December 7, 1941 and who have not violated the Constitution of IFAWA or the United States, shall be given the right to reinstate and again become members of IAWA upon payment of the current year’s dues.”[6]

The fishing industry immediately experienced problems when the US entered World War II. Several ports and fisheries in California and Alaska were shuttered for security reasons, and additional regulations were placed on fishing times and the movement of boats.[7] IFAWA successfully lobbied to reopen California, but major restrictions continued in Alaska for fear of a Japanese invasion.[8] Meanwhile, some 30% of the union’s membership joined or was drafted into the military.[9] As early as April 1942, the UFU-Puget Sound was experiencing financial problems and levied an additional assessment on top of dues.[10] Similar problems with dropping membership and financial reserves were experienced throughout IFAWA.[11]

International Fishermen and Allied Workers enthusiastically supported the war effort and maximum production in the fishing industry to feed the troops and home front. For example, a 1942 conference declared that “our responsibilities are clear, necessitating our imposing upon ourselves a strict Union discipline to carry through our tasks. We want greater efficiency, greater production. No obstacle can be allowed to stand in the way. Production must be stepped up to the maximum, commensurate with the conservation of our fisheries, and to this end we must critically examine existing methods and regulations.”[12] The statement was intended to showcase the patriotism of fishermen while pushing for their right to work without restriction. In addition to lobbying on geographic restrictions, the union adapted its grievance handling procedures to advocate for members in front of draft boards.[13] In a letter to a board on behalf of a member who had caught the equivalent of 38,000 half-pound flats of canned fish the prior season, Jurich wrote that “now the question quite naturally arises: can he best serve by producing food fish, or remaining in the armed forces and forgo producing this or a like amount of essential food next year?”[14] IFAWA was successful in getting many fishermen classified as ‘essential’ defense workers that were thereby exempt from the draft. Additionally, the union convinced the government to allow members who had been classified as essential defense workers in their off-season jobs to have the option of temporarily leaving these positions to fish.[15] In spite of the rule change, many skilled fishermen remained in defense plants and the availability of experienced crewmembers was limited throughout during the war.[16]

The union followed the labor movement’s wartime policy of maintaining industrial peace so as to support the war effort, but was not entirely acquiescent. Two months after Pearl Harbor, the IFAWA newspaper opined that “Production of food in the fight for freedom requires full and complete cooperation between labor, government, the industry and the War Department if maximum production is to be achieved.”[17] IFAWA and other unions that represented workers of the Alaska Salmon Industry (ASI), the employer’s association of most packers operating in the Territory, proposed a joint-labor management steering committee to set business practices and policy. The permanent committee would have had equal numbers of labor and corporate representatives, with a tie-breaking vote going to a government mediator. The ASI strongly opposed the idea and would only accept an ad-hoc committee to address issues directly related to the union. The Alaska Fishermen’s Union also used the new opportunity structure to push for a radical shift in labor relations with the ASI, asking for a monthly wage and profit-sharing in which a percentage of the season’s earnings would be distributed to workers.[18] They were similarly rebuffed. The United Fishermen’s Union had more success with the Puget Sound salmon packers, who agreed to a joint union-industry council that held framework talks on price agreements.[19]

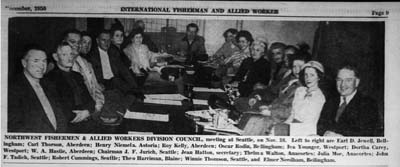

The Northwest IFAWA Council brought together fishing and shoreworker locals

and showcased the rise of women leaders within the union.

International Fishermen and Allied Worker, December 1950,

The membership was not always in agreement with the leadership about a restrained wartime stance on industrial relations. In July 1943 the membership voted down a recommendation by the Executive Council of the United Fishermen’s Union to roll-over the previous Puget Sound Salmon Agreement. At that year’s convention there was reticence about endorsing the CIO no-strike pledge.[20] Attacks on the union had not stopped with the war, and workers were reticent to give up their strongest tool – the strike – when the packers and government continued to use legal suppression. Attacks on the associational rights of fishermen continued with a federal anti-trust indictment against the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union in 1942. Additionally, the Office of Price Administration (OPA), tasked with rationing and oversight of consumer goods during the war, imposed harsh and artificial limits on the earnings of fishermen. Despite debate over the proposition, there was never any real question about IFAWA’s compliance with the no-strike pledge. Without the strike, the union turned to government regulation to protect working conditions. If an impasse was reached in negotiations, the union could seek mediation by the Department of Labor’s Conciliation Service. Next, it could ask the War Labor Board to impose a favorable settlement on a company.[21]

The union remained internally cohesive as the politics of the Yugoslavian membership base converged with those of the Communist Party-connected leadership. In 1941, the Balkans were occupied by Germany and a united resistance known as the Partisans was formed by the regional Communist Party and its leader, Josip Tito. Working-class Yugoslavian immigrants, who on the West Coast concentrated in the fishing industry, often supported the Partisans.[22] In 1944, the United Fishermen’s Union Executive Council authored a “Resolution Supporting Yugoslav Peoples Liberation Armies” urging the US government to support the Partisans, and gained support for the measure from the Seattle and San Francisco Industrial Union Councils.[23] IFAWA locals raised money to support the Yugoslavian people and the Partisans throughout the war, and longtime IFAWA leaders like George Ivankovich and Joe Jurich doubled as officers of solidarity organizations.[24] After Yugoslavia was liberated, its delegate to the United Nations met with IFAWA members.[25] After the war, IFAWA members successfully demanded the US investigate allegations that Tito was diverting food aid to the Army, charges which had suspended humanitarian aid through the United Nations. The investigation led to a reinstatement of aid.[26] These struggles united Communist leaders with rank and file members who possessed a strong sense of transnational solidarity, and further cemented the cohesion created during the organizing struggles of the late 1930s.

IFAWA was a Communist-led union that had its roots in Party organizing. Beyond that, the records do not permit solid conclusion on the extent to which the Party tried to control the union or the attitude of the rank and file toward leftism. Several leaders of IFAWA were Party members with no background in the industry, like Jeff Kibre. Paul Dale was a first-generation immigrant that grew up in the fishing community of Astoria, but was also a college-educated Party organizer.[27] It is unclear if Joe Jurich, the Tacoma-born President of the International, was ever a Party member.[28] He was accused during some Red Scare hearings of supporting the Party, but not of actually being a member. The only evidence presented in the hearing was actions Jurich took in compliance with Convention resolutions, for example publicly opposing the imprisonment of Communist Party USA leader Earl Browder.[29] It was routine for Conventions and other conferences and meetings to support causes and front groups linked to the Communist Party, and there was rarely dissension. Progressive and leftist delegates probably self-selected to attend these meetings, but in affiliates and locals conducted votes on the proposed resolutions beforehand and instructed their delegates on how to vote. On the Earl Browder resolution, a delegate of the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union voted against the resolution saying his local had instructed him to oppose it, but noted that he personally supported the measure.[30]

Most evidence of Communist connections comes from the upper level of the union. The union’s lawyer, George Andersen and his firm were deeply tied to the Party. Paul Pinksy, who assisted IFAWA on legal issues while a staffer for the California CIO and later defended the union in front of a CIO board that expelled the union from the federation for Communist influence, was named as a Party member.[31] The experience of solidarity with the Partisans suggests a left-leaning membership, at least among the union’s base of Yugoslavians. However, the extent of radicalism among the rank and file is impossible to ascertain, and support of Tito may have had more to do with anti-fascism and ethnic nationalism than leftism. There was never public discontent with the politics of the leadership until the Red Scare began to build and the union entered a difficult period in the late 1940s. Even then, opposition was limited and isolated.[32] IFAWA was a platform for agitating on many Communist causes like the Civil Rights Congress or the International Labor Defense, and the newspaper carried occasional stories like “Soviet Fishermen’s Union Controls Vast Industry,” which glorified union democracy and workplace control in the USSR.[33] However, the union’s main business was always bread and butter improvements and it consistently delivered. Leadership was opaque about their Party affiliations out of necessity but never hid their political leanings and seemed to have a relationship with the rank and file that went beyond workplace issues.

On another front, the war brought important internal changes to the composition of the union when large numbers of women entered the industry for the first time. Many women worked in the canneries before the war, but had faced discrimination in hiring, job assignment and pay. The constriction of the male workforce led to expanded opportunities in canneries, and soon manifested in a growing cohort of women union leaders. A handful of cannery women had been union leaders, representatives and delegates before the war, but their influence was limited by the almost all-male fishing workforce. As of 1940, only one woman had ever been member of the United Fishermen’s Union who was not a shoreworker. She was Betty Lowman, a resident of Bellingham who paid for her education at the University of Washington by reefnetting off Lummi Island and crewing halibut boats in Alaska. Lowman had been active in the union as a representative of her local, but remained an anomaly in the commercial fishing section of the union outside a few women who fished alongside their families.[34]

Rosalie Norton, Secretary of IFAWA Local 35

Women made up a large number of the voting delegates from cannery locals at the 1943 IFAWA Convention and one served as the official delegate to the CIO Convention.[35] A resolution at the prior year’s Convention brought by six female delegates, Jurich and Vice-President Hecker is exemplary of the progress made, as well as its contradictions. The resolution stopped short of recognizing women’s right to work outside of wartime and advocated that single women be hired before those who were married and therefore likely had children. Nevertheless, the resolution also took a progressive stance in favor childcare, equal pay and training programs for cannery positions from which women had traditionally been excluded. Despite the continued articulation of a patriarchal attitude toward women’s participation in the workforce, these measures were groundbreaking. The resolution concluded by stating that “we further call upon our unions to recognize the presence of millions of women workers in industry and devote special study to the problems of such workers, to the opportunities created by their employment, and make full use of the qualities of initiative and leadership that they can bring to IFAWA.”[36] On the latter, the union succeeded in incorporating women as equal members and leaders of the union, but there is no evidence of a concerted attempt to end unequal pay, which persisted for some cannery workers until the 1950s and 1960s.[37]

Winnie Thomson is the most striking example of female leadership in this period. She was an active member and staffer of the UFU’s Fish Reduction and Saltery Workers Local 7, a member and trustee of the International Executive Board, IFAWA representative to the Washington State Industrial Union Council, Secretary-Treasurer of the Northwest Cannery Workers Conference, and an active member of the Northwest IFAWA Council. [38] Although there was not meaningful progress on pay equity, the equal footing given women as leaders at all levels of union vindicated their work in the canneries against devaluation and marginalization. Women often worked some of the hardest and more manual jobs like sliming – washing down the fish – while men were given the supposedly more skilled positions tending machines.[39] During the war, the CIO’s newspaper often carried pin-up photos, and the practice stuck after the war. IFAWA’s newspaper was in the habit of reprinting these photos or printing their own, but unlike the CIO News it was common to see women in photos of union meetings and the shop floor. The juxtaposition of these images in the pages of the International Fisherman and Allied Worker embodied the union’s mixed record on gender, which moved toward the valuation of women’s work and leadership but failed to fully break free of gender norms.

As the war dragged on, IFAWA continued to need intervention by government agencies to gain minimum standards. In 1943, the War Labor Board awarded a 7% pay increase to IFAWA members working for Alaska Salmon Industry companies. However, the ASI steadfastly refused to pay the mandated pay rate. The hardened stance of the ASI pushed the limits of the Board’s power, whose orders were simply ignored by the packers. The case dragged on until after the summer Alaska fishing season ended, and its resolution is unclear. The silence of IFAWA sources on the case suggests they lost.[40] Once again, the United Fishermen’s Union found it easier to win in the Puget Sound than against the massive Alaskan industry. They successfully won back pay for tendermen and cannery workers whose wages had been frozen at 1942 levels by the Federal War Labor Board.[41] At the same time, the UFU suffered a major loss in May 1944 when Secretary-Treasurer and longtime organizer Paul Dale died suddenly from a heart attack.[42] Jurich stepped in to fill his position until Anton Susanj was elected to Dale’s former position. Susanj was a skilled and committed leader, but lacked the extraordinary zeal of Dale, who carried out with unflagging energy the internal management of the UFU, member organizing, contract negotiations, and endless leadership meetings from the local level to the International.[43]

After the initial shock of the war, IFAWA regained its balance and began using the changed conditions as an opportunity to expand. A smaller workforce allowed it to boost union density and laid the foundation for post-war growth. One important example of the union’s extension is the formation of IFAWA Local 46, which represented Alaska Native cannery workers in Bristol Bay. Before the war, Alaska Natives had been systematically discriminated against in hiring. When they did manage to secure cannery jobs, they were treated and paid as second class workers. With the constriction of the available workforce, exacerbated among cannery workers because of the restrictions on work and travel by Asian-Americans, canneries hired Alaska Natives in significant numbers.[44] A construction boom of infrastructure like roads, in the interest of defense, facilitated better Native access to the far-flung canneries dotting the coastline.[45] Whereas in 1937 the Bristol Bay cannery workforce was comprised of 194 Alaska Natives and 4,238 non-resident workers, some wartime canneries employed mostly Natives.[46]

Joe Nashoalook, Secretary of IFAWA Local 46 in Bristol Bay,

and Rosalie Norton of Local 35

The conditions faced by Alaska Native cannery workers are a stark illustration of the colonial relationship between the Territory and the absentee packing corporations that operated with little regard for the area or the welfare of its people. The non-resident cannery workers, mostly Filipinos and Asian-Americans, faced tough conditions like cramped bunkhouses and daily discrimination by white management. But their problems paled in comparison to those of the residents. The resident Native workers received lower pay when they performed the same jobs and non-residents, and often worked before and after the season, yet still received lower take-home earnings than the non-residents. This was particularly egregious because of the higher cost of living in Alaska, where manufactured goods had to be shipped from the lower 48 states. The Native workers, especially before the war, functioned as a reserve pool of labor in the case of an unusually big fish run or an inadequate number of non-resident workers. As such, they were not given company housing and lived in self-constructed shacks that one former manager compared to Hoovervilles. The isolation of the canneries meant that the only source of food and supplies were company stores. As traditional lifestyles that incorporated seasonal migration and self-subsistence eroded, Natives increasingly stayed in these small company towns. Company stores trapped them in debt cycles and guaranteed their presence during the next season as a cheap pool of reserve labor. When working in the canneries, Natives were segregated to a separate section of the cafeteria.[47] The packers were responsible for most of these aspects, but the Alaska Fishermen’s Union and other non-resident unions were complicit in this set-up. For example, packers in Bristol Bay would hire a certain number of fishermen per cannery assembly line. The AFU long maintained contract clauses that required thirteen non-resident fishermen be hired per line before a single resident. In addition to the direct effect of shutting Native fishermen out of work on boats, it indirectly reinforced the resident community as reserve labor making cannery work the only available source of income.[48] Discrimination in the Alaska Fishermen’s Union subsided somewhat in the IFAWA years, and they organized resident fishermen and some cannery workers. Nevertheless, branches located in the Territory complained of being ignored and sidelined by the lower 48 leadership, and in 1949 they were still barred from voting for the leaders of the AFU.[49]

These problems faced Native cannery workers throughout Alaska, but were most pronounced in Bristol Bay, where isolation allowed an even greater degree of company control and manipulation. There, IFAWA Local 46 took root as one of the union’s most dynamic and unique sections. The Local is the strongest piece of evidence that the union was genuine in its rhetoric that opposed absentee exploitation of the Territory. As the union representing workers in the largest and most strategic industry of Alaska, IFAWA was in a prime position to challenge the exploitation of the Territory, but was hamstrung by residency issues.[50] IFAWA long supported statehood as a tool for the Alaskan people to reclaim control of their resources, and enthusiastically supported industrialization and modernization as an alternative to absentee extraction and underdevelopment. This produced a complex relationship with Alaska Natives. IFAWA’s pro-development stance respected Native wishes to regain control of their communities and lands, but also pushed for assimilation to keep pace with modernization and staunchly opposed tribal sovereignty that might restrict where white fishermen could operate.[51] At the same time IFAWA was first organizing Native cannery labor, it was working with the Alaska Salmon Industry to oppose overtures by the federal Department of the Interior to give Indian groups reservations and exclusive fishing rights. The union walked a thin line in opposing the measure. IFAWA argued that the measures were a form of segregation or even “glorified concentration camps,” that the industry was based on cooperation not racial exclusivity, and that the union opposed special privileges for any group of “Americans” but was wholly ready to support legal action by Natives to receive compensation for past injustice.[52] IFAWA was a diehard opponent of fish trap use in Alaska, which continued to allow this low-labor, high-capital fixed gear to be used long after it was banned on the rest of the Pacific Coast. Perhaps more than any other issue, it tied IFAWA’s membership together. The opposition was against the large packer-owned traps that caught up to 44% of the Alaska catch, not traditional Native traps for personal use.[53] However, a racialized rhetoric was sometimes adopted in opposing corporate traps, calling it an uncivilized and barbaric practice. Conversely, the union occasionally proposed that bans not apply to Natives who used traditional traps for subsistence.[54] The variance of this rhetoric and the coexistence of Local 46 with exclusivist elements in the Alaska Fishermen’s Union suggest that IFAWA was deeply, if quietly, divided on the rights of indigenous peoples and Alaskan anti-colonialism.

The quick change in the composition of the Alaska cannery workforce led to a complicated fight between IFAWA, the CIO cannery workers union, the Alaska Native Brotherhood and the AFL for the ability to represent the burgeoning group. The Brotherhood was a pan-Native organization that engaged in collective bargaining as well as civil rights issues. It initially had a friendly relationship with the United Fishermen’s Union, and Native Brotherhood leader William Paul spoke at the IFAWA-led conference of Alaskan CIO unions in 1940. [55] Both groups pursued a similar strategy that focused on fishermen instead of the relatively small number of Native and white resident cannery workers. UCAPAWA Local 7, the union of Asian-American non-resident cannery workers based in Seattle, resented the Alaska Native cannery workers in the pre-war era because they were cheap reserve labor that could undermine their bargaining power.[56] Gender dynamics may have played into these choices as well. Fishermen and non-resident cannery workers were exclusively male groups and pre-war Native cannery workers were usually women.

Because Local 7 had exclusive rights to represent all non-resident cannery workers under a National Labor Relations Board election, and because the Alaska Fishermen’s Union, United Fishermen’s Union and IFAWA were the more popular organizations among non-resident fishermen, the AFL pursued organizing among resident cannery workers years before World War II. They met with limited success, and only represented 1,300 of 4,500 resident cannery workers in 1939. The AFL, like IFAWA, rhetorically positioned itself as the defender of Alaskan interests. However the Alaskan AFL did not have to answer to a sizeable non-resident membership pursued a more aggressive strategy summed up by its oft-used slogan ‘Alaska for Alaskans.’[57] Initially used to build a strong base among white residents in fishing and other industries like construction, it was later adapted to organize Native workers.

All four actors– IFAWA, various Seafarer or other AFL affiliates, the CIO cannery workers union and the Native Brotherhood - scrambled to snap up the new and unorganized group of Alaska Native cannery workers. IFAWA was at odds with the CIO cannery workers, who had undergone a name changed from UCAPAWA to the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers of America (FTA). Though tensions were high, they remained committed to settling jurisdictional disputes within the CIO. The two unions had the most momentum, leading the AFL and the Native Brotherhood to form an alliance around their common enemy paint the CIO as another tool of outside interests.[58] The National Labor Relations Board held several regional and plant-specific elections between 1945 and 1947. IFAWA won an election to represent all resident cannery workers in Bristol Bay, and the FTA gained a majority in a similar election for the Alaskan Peninsula. There was no master election for the Southeast Alaska area. It appears that the AFL and Native Brotherhood and split up the area on a company-by-company basis.[59]

The cannery dispute was just one of many challenges accompanying the end of the war. At the December 1944 Convention, Vice-President Hecker argued that “The battle for freedom and democracy the world over will soon be won, but the battle for decent wages and working conditions the world over is just beginning, and now more than ever it becomes the responsibility of the large labor unions to see that we at least retain the gains that we have made over a period of years.”[60] With chilling foresight, he predicted that big business was preparing to attack labor as soon as the war was over. For the time being, IFAWA scored a major victory when the War Labor Board ruled that “Fishermen - independent and company - in reality are laborers (not entrepreneurs) who furnish in a variable degree the tool of their trade… in the view of the fact that fishermen are essentially a labor force, it is recommended that for purposes of negotiations and bargaining relationships, any dispute between fishermen (company and independent) and industry shall be regarded as a labor dispute.”[61] IFAWA also made significant progress on harmonizing contract standards between locals.[62]

The main priority for 1945 was to make commercial fishing a priority in the creation of a post-war economy. For over three years, the American economy had been oriented toward a single goal: winning the war. As it became clear that Allied victory was inevitable, the watchword became ‘reconversion,’ the process of adjusting the economy back to a normally functioning state. Fishermen and cannery workers had chaffed under the restrictions set forward by the Office of Price Administration (OPA), which created ceilings on the prices paid to fishermen based on the 1942 season, an unusually poor one with below average prices. The union argued that the ceiling did nothing to reduce consumer costs, and existed solely as a drain on the livelihoods of fishermen.[63] The speedy removal of the limit upon reconversion became a major demand for IFAWA.[64] Additionally, the union saw reconversion as an opportunity to end the inequities of the past, when commercial fishing occupied a marginal position in US food production. Even before peace was settled with Japan, Jurich travelled to Washington, D.C. to lobby for greater government attention to the industry.[65] The argument presented to lawmakers and the public was two-fold. First, fishing had been essential to winning the war, and fishermen had greatly sacrificed to maximize production. Second, fishing deserved to be subsidized the same as agricultural food production. The union’s argument gained the support of the House Subcommittee on Fisheries, but no action was ever finalized.

Despite these setbacks, in November 1945 President Truman issued a proclamation and strategic plan for the American fishing industry. It lavished praise on the workers of the industry and met several of their demands on regulation and the ability to fish in international waters, but neglected to address the role of the industry in reconversion.[66] Additionally, a rare victory was achieved when IFAWA worked with progressive Seattle congressman Hugh DeLacey to force the Office of Price Administration to abandon its price ceiling for Alaska.[67] IFAWA remained hopeful that it could score other victories, especially, with the end of the no-strike pledge, and decided to re-open all contracts in 1946 to “straighten out [the] many inequalities and injustices which have existed in our Agreements.” [68] However, the end of the war also meant that sizeable government and Army purchases of fish declined rapidly. IFAWA asked that this de facto subsidy be maintained at wartime levels and redirected for use as foreign aid in reconstruction efforts. In another example of the fusion of practical and leftist concerns, IFAWA joined other waterfront unions in advocating for normalized trade relations with communist China to create new economic opportunities.[69]

In 1946, the union redoubled its efforts to carve out space for fishing in the American economy. A Convention opened the year with a focus on ‘streamlining’ and ‘modernizing’ the industry. The approach mixed boosterism, including joint advertising campaigns with the packers to educate the public about the health benefits of seafood, with redistributive demands for a greater share of profits. The union believed the packers were more interested in short-term profits than long-term success, and argued that the companies intentionally kept commercial fishing and canning marginal to the overall American economy. A member of the International Executive Board argued that the packers planned “on taking care of everything by cutting down on production and lowering wages. Solving some of these problems will make for progress in the industry. I reiterate, IFAWA should take the lead.” This rhetoric portrayed workers as the more responsible part of the sector, interested in the common good and the improvement of all workers and consumers. A detailed plan was created to expand the use new technology like radar, refrigeration and freezing, and to reduce waste in processing by utilizing non-food byproducts.[70]

The Fishermen’s Fiesta in San Pedro was part of IFAWA’s effort to

promote seafood consumption and industry modernization

In this way, technological upgrades and modernization were linked with the betterment of life and work in fishing. The union declared that “The time is here to put up or shut up in the fight for a modern industry and a square deal for producers and shoreworkers.” The statement continued in ever more dramatic terms, “This union has an historic mission virtually unparalleled in the labor movement; the job of helping to modernize an industry. Nor is this merely a crusade; we either modernize and expand production or our fishing fleet is doomed to bankruptcy.” IFAWA was frank about the challenges of the post-war fishing industry, and explained that “Hard economic facts compel this convention to dedicate itself to fighting for an industry that will ‘make every day fish day’ for producer, shore worker, operator and consumer.”[71] Out of this approach grew a peculiar alliance with Nick Bez, colorful vessel owner, Croatian immigrant and millionaire. He was a consummate industrialist with investments in mining, airlines and canneries, but Bez also had liberal sympathies and served alongside Jurich on the Free Yugoslavia solidarity committee.[72] Bez pioneered the use of massive ships that froze and processed fish onboard. This allowed for longer offshore trips that became necessary with the ecological depletion of the West Coast fishery. One of his first boats, the Pacific Explorer, plied the waters off Costa Rica using a union crew. The venture ignited a firestorm of criticism over potential violations of international law and ecological destruction. Jurich leapt to the defense of Bez, testifying before Congress on the virtues of the project.[73]

The Pacific Explorer highlighted the complex relationship between IFAWA and conservation. The union tried to balance the immediate material needs of its members with long-term sustainability that would guarantee jobs in the future. They had no interest in ecological diversity for its own sake, and often advocated for the wholesale elimination of predators like sea lions. An IFAWA affiliate once asked the Army to bomb seals out of existence near the entrance to the Copper River.[74] Nevertheless, the union was a constant supporter of greater scientific research to protect fish stocks.[75] In 1947, it decried studies of salmon that examined each part of the life cycle in isolation, and the general “horse and buggy” style of conservation research. They made the common sense assertion that “studies should guide the development of fisheries, not follow in the wake of exploitation.”[76] Given the massive underfunding of government research, IFAWA was often justified in questioning arbitrary regulatory restrictions imposed without adequate data collection or consultation with the fishermen who knew the catch best. However, pure self-interest was at play in most of these disputes.

IFAWA targeted its conservation efforts at outside factors that might damage fish runs. It strongly opposed pulp mills, industrial pollution, agricultural land reclamation that destroyed streams, and the massive dams that were constructed in Northwest during the 1930s and 1940s. The unofficial artistic voice of the CIO, Woody Guthrie, may have lauded the Northwest dams, but IFAWA remained firmly opposed.[77] Initially, union outright opposed dams, but it became clear that the union lacked the leverage needed to stop the projects. By the 1940s they shifted toward a strategy of negotiating compensation in the form of fish ladders, hatcheries and other restorative measures.[78]

Any semblance of support for the regulation of catch size was abandoned amidst the union’s ‘win-the-war’ program of ‘all-out production,’ but this also came at a time when crews and canneries were chronically understaffed, creating informal catch limits. When the war ended, the focus on modernization meant evermore efficient methods put greater stress on fish stocks. Some methods like trawling created a large ‘bycatch’ of unintentionally captured marine wildlife that was discarded. However, the union placed a good deal of focus on the elimination of wasteful methods and advocated that the bycatch be used in whatever commercial way possible.[79] IFAWA expressed concern about the increasing number of boats in the post-war period, though concern arose mostly from the fear that more fishermen meant lower earnings. By then, the writing was on the wall for the West Coast fishing industry. Overfishing had long been evident and fish stocks would begin to rapidly worsen in the mid-1950s. In 1948, sardines became the first West Coast fishery to fully collapse. Though it is now believed that the collapse was cyclical, it failed to spur the union to change its conservation approach.[80]

Meanwhile, the diligent approach toward organizing during the war paid off after 1945. Membership recovered to over 20,000 and the union proved itself an attractive option for fishermen who wanted to organize. For example, 300 Puget Sound crab fishermen organized independently but were unable to convince their employers to bargain, so they joined United Fishermen’s Union (UFU) to gain the necessary leverage to be recognized.[81] Additionally, the UFU conducted a major cannery worker drive in 1945 that added 450 members.[82] Since its California wing had collapsed in the early 1940s, the United Fishermen’s Union of the Pacific was in reality a Washington State organization with a few members that worked as non-residents in Alaska. In 1946, it changed its name to IFAWA Pacific District Local 3, hoping to bolster unity and identification with the International. In practical terms, this had little effect. Locals became known as units, but they functioned exactly as before.[83] Susanj continued as Secretary-Treasurer and Reduction Worker representative Robert Alvestad took over from Oscar Rodin as President.[84]

The UFU’s new name reflected a general sense of post-war optimism. ‘Pacific District’ implied that there could soon be districts for the Atlantic, Gulf and Great Lakes. There was some initial progress on this front when around 175 Lake Erie fishermen who belonged to the International Longshoremen’s Association, the more conservative counterpart to the ILWU, defected and joined IFAWA.[85] Forming IFAWA Local 63, they launched a hard-fought strike just months after joining and stayed out for 235 days.[86] In the Gulf Coast, the CIO’s National Maritime Union facilitated a meeting that drew 125 fishermen and established a new IFAWA local.[87]Additionally, Jeff Kibre travelled the Gulf Coast and South Atlantic to court several federations of fishermen’s organizations, which had a combined membership of 10,000.[88] Though halting, these were important steps that accompanied significant expansion among West Coast shoreworkers and Alaskan fishermen.[89] Seven new locals of IFAWA were chartered in 1946, including two in Alaska, and the Alaska Trollers doubled their membership.[90]

The lifting of the no-strike pledge unleashed a wave of militancy in IFAWA and across the nation. One of the most important actions by shoreworkers was a joint strike of IFAWA Local 46, representing Alaska Native cannery workers in Bristol Bay, and Local 7 of the Food, Tobacco Agricultural and Allied Workers, which represented the mostly Filipino cannery workers who shipped out of Seattle, Portland and San Francisco. The strike began on April 20th, shortly before the date when Local 7 members would normally begin to ship out. In addition to the work stoppage, pickets in Puget Sound and Alaska prevented the shipment or unloading of cannery equipment. The impact of this blockade was compounded by an 18-day longshore strike in Alaska that ended April 22nd.[91] The partnership of Local 46 and Local 7 proved extremely valuable when the two devised a plan to allow some shipments of food to Alaska on April 25th, staving off a food shortage.[92] The strike was lifted April 27th with a 10% wage increase and an extra $25-50 in standby pay during times of inactivity for Local 7 members. Residents in IFAWA Local 46 achieved an hourly minimum of $1.06, up from 96 cents, and an increase of $50-$90 in guaranteed earnings for the season.[93] The show of strength allowed Local 46 to keep negotiating throughout the season, and by July it negotiated additional gains that increased the pay of the lowest classification to $1.10 an hour, with top classified cannery workers earning $1.35. They also achieved a closed shop, an eight hour day, and company recognition of shop stewards. In a very rare victory, unequal pay was eliminated for women. The contract barred the packers from paying women ‘Class B’ wages when they performed work consistent with ‘Class A’ male workers. This is the only IFAWA contract examined by this study in which discrimination in pay and classification is directly prohibited.[94] The campaign was also a remarkable example of CIO civil rights unionism and working class unity between two disparate groups – Alaska Natives and Filipino migrants – who shared common experiences with American empire and exploitation by capital. The specifics of their encounters with global imperialism were different, but the underlying commonality of their two experiences is strong. Within the CIO, the two groups had found a home and, more importantly, the tools and support network needed to fight back against the grueling conditions of the canneries. Together, they challenged companies that presumed to run Alaska by fiat and tried to use race to divide and conquer their workforce.

Above the local level, the strike was important because it allowed IFAWA and the FTA to set aside growing tensions and work together. The contentious debate over the representation of resident Alaska cannery workers opened up longstanding jurisdictional gray areas in the CIO.[95] To iron out the issue, the leadership of IFAWA and the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers (FTA) formulated a merger proposal and brought it the fishermen’s 1946 Convention. The idea failed to gain traction. Convention delegates complained that the proposal was a quick-fix which was not motivated by fraternal feelings of unity. Accusations flew that the FTA and its predecessor, UCAPAWA, had ignored resident cannery workers for several years, even though the same could be said of IFAWA. Proponents argued that a merger would give IFAWA a better foothold in the Gulf of Mexico and East Coast, and that a single union could rebuff the alliance the between the Alaska Native Brotherhood and the AFL.[96] Ultimately, the idea was tabled and no action was taken. [97]

While the two unions were winning in Alaska, they were facing problems in California. The FTA lost a major battle with the Teamsters over fruit and vegetable canneries, and Southern California continued to be the weak point of IFAWA. The same was not true in the other part of the state. In 1944, IFAWA signed the Northern California Fish Stabilization Agreement, its first master price agreement.[98] It covered prices for all fish sold fresh instead of being canned. IFAWA Local 36, the consolidated representative for all Southern California fresh market fishermen, tried to follow this lead and proposed a Southern California Market Fishermen’s Master Agreement in spring 1946. Thirteen dealers – the term for fresh market companies – refused to negotiate and 1,100 members of Local 36 struck in response. As with many IFAWA tie-ups, a portion of the membership continued to fish for less antagonistic employers. After two weeks, Local 36 and the obstinate dealers came to a compromise in which a minimum price would be established and negotiations would take place daily concerning payment above the minimum. The compromise included a promise from the dealers to negotiate a master agreement for Southern California if the Northern California agreement was legally certified.[99] However, the dealers and the government filed an anti-trust case against Local 36, some of whom were boat owners. They argued that their strike did not constitute a dispute under labor law and was an unlawful attempt to induce negotiations.[100] The anti-trust case came in the form of criminal charges brought by the Department of Justice via grand jury against the officers of Local 36 and International Secretary-Treasurer Jeff Kibre.[101] It was a dangerous alteration of the old anti-trust strategy. Previous anti-trust suits had been civil injunctions against organizations that barred them from bargaining, and allowed groups like the Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union to reorganize under a new name. The new anti-trust strategy criminalized unionism and made officers vulnerable to punishment and jail time. The reverberations of the lawsuit worsened a difficult situation for the rest of IFAWA, which was only beginning to see the end of Office of Price Administration restrictions in fall 1946.[102] A small victory was achieved when the Assistant Attorney General refused to bring criminal charges against the Alaska Fishermen’s Union as requested by the Alaska Salmon Industry.[103] This joined other successes like the 1946 cannery workers strike and the expansion of membership, which helped to balance the frustrations in making commercial fishing a central part of the post-war economy. These strengths and weaknesses were about to be put to the test as post-war labor relations became a battleground in 1947.

[1] Resolution 34, Proceedings of the Convention of the United Fishermen’s Union of the Pacific Puget Sound District, Monday December 2nd, through Wednesday, December 4th, 1940, Seattle, Washington. CIO. box 4, folder 38

[2] Executive Board SPSU October 16, 1937. box 5, folder 10First Annual Convention Federated Fishermen’s Council of the Pac Coast. Astoria, December 13-18 1937. box 12, folder 21. Page 32, 41.

[3] Third Convention, December 1-5, 194, box 12, folder 2, page 13

[4] IFAWA Views the News, February 10, 1942, box 11, folder 15.

[5] Chiang, Shaping the Shoreline, 105-8.

[6] Local 3 Executive Board, May 10, 1947. box 12, folder 8, page 2.

[7] “In the Net,” IFAWA Views the News. January 23, 1942, box 11, folder 15; IFAWA Views the News. February 27 1942, box 11, folder 15.

[8] 4th Convention, December 1-4 1942, Seattle. box 12, folder 2, page 10.

[9] “Fishermen Free For Other Jobs.” Washington State CIO News, November 1942.

[10] United Fishermen’s Union- Puget Sound, Executive Council, April 4, 1942, box 3, folder 2.

[11] Fourth Convention, December 1-4 1942, box 12, folder 2, page 18.

[12] IFAWA Views the News, March 27, 1942, box 11, folder 15

[13] “Coordination is Needed to Protect Fishing Industry,” IFAWA Views the News, February 27, 1942. box 11, folder 15.

[14] Letter to IFAWA RE: deferment status of experienced fishermen, 1942, Lummi Island Heritage, <http://content.statelib.wa.gov/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lummi/id/876/show/874/rec/8>

[15] “Fishermen Free For Other Jobs.” Washington State CIO News, October 1942, 1.

[16] “Fishermen’s News” Washington State CIO News, December 1943.

[17] “IFAWA Proposes Fishing Industry Council Plan.” IFAWA Views the News. January 23, 1942, box 11, folder 15.

[18] IFAWA Views the News. February 10, 1942

[19] IFAWA Views the News . March 13, 1942.

[20] Fifth Convention, December 6-9, 1943, box 12, folder 2. Page 22

[21] United Fishermen’s Union Executive Council May 1, 1943. box 5, folder 1

Ibid., November 13, 1943. box 5, folder 1

[22] IFAWA Views the News, November 1, 1941, box 11, folder 15

IFAW, September 1945, 4.

[23] Resolution Supporting Yugoslav Peoples Liberation Armies, box 6, folder 1

[24]“Pedro Raises Jugo-Slav Fund” IFAW, August 1944, 8

“Free Yugoslavia Group Elects Jurich to Office” IFAW, February 1945, 19.

“Ivankovich is Reelected” March 1946, IFAW.

[25] “Fishermen Helped To Liberate Jugoslavia,” IFAW, June 1945, 3.

[26] “Yugoslavia Cleared of False Charges by UNRRA IFAW, September 1946.

[27] “Paul Dale Veteran Leader of UFU Dies” IFAW, June 1944, 5.

[28]House Committee on Un-American Activities, “Investigation of Communist activities in the Los Angeles Area” 83rd Congress; House Committee on Un-American Activities, Communist infiltration of Hollywood motion-picture industry : hearing before the Committee on Un-American activities, 82nd Congress; Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act, “The Alliance of Certain Racketeer and Communist Dominated Unions in the Field of Transportation as a Threat to National Security,” 1958.

[29] House Committee on Un-American Activities, “Report on Civil Rights Congress as a Communist Front Organization,” 80th Congress, 15. House Committee on Un-American Activities, “Report on the American Slav Congress and Associated Organizations,” June 26, 1949, 89.

[30] Third Convention, December 1-5, 1941, box 12, folder 2.

[31] IFAWA Executive Board July 17-19, 1947, box 12, folder 4, page 1; Preliminary Report on CIO Trial of IFAWA, Paul Pinsky. box 11, unfoldered; House Committee on Un-American Activities “Communist Legal Subversion : The Role of the Communist Lawyer : Report,” February 16, 1959, 28; Sydney Roger, Jessica Mitford and Julie Shearer, A Liberal Journalist On the Air and On the Waterfront: Labor and Political Issues, 1932-1990 (Berekely: Bancroft Library, 1990 (New York: Knopf, 2005) 296-7; Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (New York: Knopf, 2005), 336-7.

[32] Report of the Secretary-Treasurer to the Local 3 Executive Board, March 15, 1947, box 12, folder 8; “Another Anti-Trust Suit – By Disgruntled Former Member.” IFAW, November 1947, 8; “Shipman Fails to Appear at Meeting of Eureka Local” IFAW, January 1948, page 21.

[33] “Soviet Fishermen’s Union Controls Vast Industry,” IFAW, May 1946, 14.; 4th Convention, December 1-4 1942, Seattle. box 12, folder 2, 15

[34] United Fishermen’s Union of the Pacific, Northwest Conference, box 5, folder 1, page 5; First Annual Convention of the United Fishermen’s Union, December 5-9, 1938, box 4, folder 38, page 17; Second Annual FFC Convention, San Francisco December 12-19 1938. box 12, folder 22. Page 18;Lottie Edelman, discussed later, is another important exception: March 1948, IFAW, 8; CRFPU Business Agent Florence Plumb:“Notes from the Umpqua,” IFAW, February 194616; Ruth Weijola of the CRFPU: Proceedings, Second Convention, December 9-13, 1940, box 12, folder 2, page 33; Rosalie Norton, Secretary of IFAWA Local 35: IFAW, June 1946, 6.

[35] Fifth Convention, December 6-9 1943, box 12, folder 2, page 32.

[36] Fourth Convention, December 1-4 1942, box 12, folder 2, page 36.

[37] Puget Sound Salmon Cannery Workers Agreement, box 7, folder 3. This document shows some of the complexity of unequal pay—men and women with the same job classifications had different pay, but also different duties. This was used to justify the pay regime. Some agreements like this one guaranteed “male” pay for women workers if they performed the duties of the “male” classification.; “Costs of Production and Distribution of the Fish on Pacific Coast,” Federal Trade Commission, 13; 68; Agreement 1948 Grays Harbor Shoreworkers, box 7, folder 3.

Muszynski, Cheap Wage Labour, 215; 8.

[38] Local 3 Executive Board, September 24, 1949, box 12, folder 10; Northwest Cannery Workers Conference December 7, 1946, box 7, folder 3; IFAW, May 1948, 5; NW IFAWA Council, March 26, 1949, box 11, folder 16

[39] Muszynski Cheap Wage Labour, 12.

[40] Report to all locals, April 25 1944. Involvement of War Labor Board in Alaska Salmon Industry Inc negotiations. box 1, folder 6; UFU Executive Council, April 8, 1944, box 6, folder 1; Ibid., May 6, 1944, box 6, folder 1.

IFAWA Executive Board September 29-30, 1944, box 5, folder 12.

[41] “Sound Workers Win Pay Award” IFAW, February 1944.

[42] “Paul Dale Veteran Leader of UFU Dies” IFAW, June 1944, 5.

[43] See, for e.g. Dale’s last UFU meeting before his death: UFU Executive Council Minutes May 6, 1944. box 6, folder 1; February 23, 1944 communication to all locals, Paul Dale, box 1, folder 6; Second Annual Federated Fishermen’s Council Convention, December 12-19, 1938. box 12, folder 22, page 39

[44] Friday, “Competing Communities at Work,” 314

[45] Fourth Convention, December 1-4 1942, box 12, folder 2, page 33; VanStone, Eskimos of the Nushagak River, 80.

[46] Ibid., 79

[47] It is necessary at times to read between the lines, given his position in management, but Jonathan Hughes presents an important overview of the conditions facing Alaska Native residents in: “The Great Strike at Nushagak Station, 1951: Institutional Gridlock,” The Journal of Economic History, 42, No. 1 (1982); Karen Hébert, “Wild Dreams,”177-92; “Far North Unionists Plan 1950 Wage Boost Campaign” IFAW, December 1949, 9.

[48] Cooley, Politics and Conservation, 148.

[49] Local 3 Executive Board, January 31, 1948, box 12, page 8; IFAWA Convention 1949, Labor Union Constitutions and Proceedings, 61-65.

[50] Proceedings IFAWA convention December 6, 1944. Aberdeen. box 11, folder 17

[51] Eighth Convention IFAWA, January 24, 1946, box 11, folder 25, page 5

[52]“Secretary Ickes Plunks Indians on Reservations,” IFAW, August 1945, 3.

United Fishermen’s Union Executive Council Minutes November 11, 1944,box 6, folder 1; November 15, 1944 letter from Oscar Rodin, attached to: United Fishermen’s Union Executive Council, December 2, 1944, box 6, folder 1.

[53] Montes, Alaska Fishermen

[54] Resolution # 11. First Convention United Fishermen’s Union, December 5-9, 1938, box 4, folder 38; Resolution #2 ISU Fishermen’s Unions Convention, December 7 1936, box 1, folder 7.

[55] Salmon Purse Seiner’s Union Executive Board, November 14, 1937, box 5, folder 15.

Fifth Convention, December 6-9 1943. box 12, folder 2. Page 73

All-Alaska Labor Convention, box 5, folder 1, page 8.

[56] Friday, “Competing Communities at Work,” 311

[57] First Convention Federated Fishermen’s Council, December 13-18 1937, box 12, folder 21. Page 16; Fifth Annual Convention, Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union, January 5-15, 1938, box 4, folder 38, page 24.

[58] IFAWA Executive Board, February 10, 1945, box 12, folder 7, Page 3; United Fishermen’s Union Conference, February 11, 1945, box 5, folder 3; Report of the Officers to the Seventh Annual Convention, 1945, box 11, unfoldered, page 5; “Off the Hook” and “Officer’s Report,” IFAW, February 1945

.Special Section Regarding Jurisdictional Dispute Between IFAWA and FTA, Eighth Convention IFAWA, January 24, 1946, box 11, folder 25, page 3.

[59] “Fish Workers to Vote on Unions,” Seattle Times; April 11, 1945, 11; “Cannery Union Vote Announced” Seattle Times, October 22, 1945, 10; For a slightly different interpretation of the ANB and AFL, see: Arnold, The Fishermen’s Frontier, 149-50.

[60] IFAWA Convention, December 6, 1944, box 11, folder 17.

[61] “Salmon Packers Must Sign Contracts” March 1945, IFAW, 5; Montes, Alaska Fishermen Laws, 68-69.

[62] United Fishermen’s Union Executive Council, April 7, 1945, box 5, folder 3; United Fishermen’s Union Executive Council, September 29, 1945, box 5, folder 3.

[63] United Fishermen’s Union – Puget Sound, Executive Council, May 1, 1943, box 5, folder 1; July 31, 1943. box 5, folder 1; IFAWA Executive Board September 29-30, 1944, box 5, folder 12; “Regional Meetings Plan Stabilization,” IFAW, February 1944, 6.

[64] IFAWA Executive Board, October 11-13, 15, 1945, box 12, folder 7

[65] July 1945, IFAW; United Fishermen’s Union Executive Conference, February 11, 1945, box 5, folder 3, page 5; “We Must Plan Now For Postwar Period,” IFAW, February 1945.

[66] “What Follows Fishery Proclamation,” IFAW, November 1945.

[67] “IFAWA Blocks Alaska Salmon Price Cut,” IFAW, August 1945, 1.

[68] United Fishermen’s Union of the Pacific, Conference December. 20 & 21 1945. box 4, folder 37

[69] Seattle United Fishermen’s Union Local 4, January 9, 1946, box 1, folder 5; “News From International Office,” IFAW, June 1946, 20; “A Million Jobs Hinge on Trading With New China,” IFAW, February 1950, 13.

[70] “Steps Toward Modernizing Our Industry,” IFAW, March 1946, page 1; Report of the Officers, Seventh IFAWA Convention, 1945, box 11, unfoldered, page 3; “IFAWA Plans Overall Industry Program” IFAW, December 1945, page 1

[71] Report of Officers, 8th Annual IFAWA Convention January 21-24 1947. box 11, folder 17; Tell Your Friends, Mrs. Fisherman,” IFAW, September 1946, 11; Booklet, Fishermen’s Fiesta, October 6, 1946, box 11, folder 17

[72] “Free Yugoslavia Group Elects Jurich to Office” IFAW, February 1945; On leftist sympathies see: “Washington Scene: Gen Vaughn and the Salmon Man.” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 25, 1951, 10; “Nick Bez,” Harbor History Museum, <http://harborhistorymuseum.blogspot.com/2012/06/nick-bez-nikola-bezmalinovic.html>

[73] “The Case of the Pacific Explorer,” IFAW, May 1947, 3

[74] United Fishermen’s Union Executive Council Minutes January 8, 1944. box 6, folder 1, page 4; Resolution #31 First Convention United Fishermen’s Union, December 5-9, 1938, box 4, folder 38.

[75] “University of Washington Research Agreement,” box 14, folder 43

[76] Report of Officers, 8th Annual IFAWA Convention, January 21-24, 1947,box 11, folder 17

[77] Jeff Brady, “Woody Guthrie's Fertile Month on the Columbia River,” NPR, July 13, 2007 <http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=11918998>

[78] Resolution #11, ISU Fishermen’s Unions Convention, December 7, 1936., box 1, folder 7; Resolution #29 United Fishermen’s Union - Puget Sound, Convention, December 2-4, 1940, Seattle, Washington. CIO. box 4, folder 38.

Salmon Conservation in the State of Washington, Yearbook, Second Convention IFAWA, box 12, folder 2, pages 14-15; Second IFAWA Convention, December 9-13, 1940, box 12, folder 2, page 44; Third IFAWA Convention, December 1-5, 1941, box 12, folder 2, page 64; Resolutions #3, 4, 6,7, 8 & 12, Eight IFAWA Convention, January 21-24, 1947, box 11, folder 19; Northwest IFAWA Council, March 26, 1949; “We Can Have Power and Salmon – With Proper Planning,” IFAW, January 1948, 9.

[79] Report of Officers, Eighth IFAWA Convention, box 11, folder 17; IFAWA Views the News, March 27, 1942, box 11, folder 15.

[80] “What Happened to Our Sardines Last Season?” IFAW, April 1946; Ninth Convention IFAWA, January 20-23, 1948, box 11, folder 24, page 19; IFAWA Executive Board August 26, 1948. box 12, folder 6

[81] November 9, 1946, box 12, folder 11; First Conference Pacific District Local No. 3, December 20, 1946, box 12, folder 11, page 21.

[82] United Fishermen’s Union report, booklet, in: Eighth Convention IFAWA, box 11, folder 25, page 44.

[83]Resolution No. 1, Authorizing the Transfer of the Property and Funds, box 12, folder 11.

[84] IFAWA, Pacific District Local 3 Executive Board April 6, 1946. box 12, folder 11;“Robt. Alvestad is Elected” IFAW, April 1946.

[85] “Lake Eire Fishermen Join New IFAWA Local,” IFAW, August 1946.

[86] “Local 63 Strike On Lake Erie,” IFAW, November 1946, 24; “First Victory Won in Great Lakes Strikes,” IFAW, June 1946, 17.The long-term existence or success of this local is unclear.

[87] “Gulf Coast Organizing,” IFAW, May 1946, 17

[88] “Survey of Gulf and So. Atlantic Fisheries,” IFAW, June 1946, 1

[89] Eighth Convention IFFAWA January 24, 1946. box 11, folder 25, page 21

[90] “IFAWA Is Growing,” IFAW, January 1947, 3.

[91] “Food Shortage Alarms Alaska,” Spokane Daily Chronicle, April 22, 1946, 9.

[92] “US Faced With New Shutdowns,” Painesville Telegraph, April 25, 1946, 1.

[93] “Alaska Canner Victory by CIO,” IFAW, May 1946, 18. On the strike, see also: “Alaskan Territorial Governor Ernest Henry Gruening telegram regarding the demands of cannery workers during a strike in Alaska, April 20, 1946,” Cannery Workers & Farm Laborers Union Local 7. Accession No. 3927-001. box 23/40, University of Washington Special Collections. http://content.lib.washington.edu/u?/pioneerlife,10650; “Alaska Sailings On; Strike Ends,” Seattle Times, May 1, 1946, 15.

[94] “Bristol Bay Residents Get More Cannery Pay,” IFAW, July 1946, 6.

[95] IFAWA Executive Board February 10, 1945, box 12, folder 7,vpage 3; United Fishermen’s Union Conference February 11, 1945, box 5, folder 3, page 2

[96] Special Report Regarding Jurisdictional Dispute Between IFAWA and FTA, Eighth Convention IFAWA, January 24, 1946, box 11, folder 25, pages 1-5 (day 1);

[97] United Fishermen’s Union Executive Board, February 9, 1946, box 12, folder 11.

[98] ASI negotiations were jointly conducted, but each union signed a separate agreement and prices and standards usually varied

[99] Pinsky, Fisheries of California, 96-106.

“So. California Strike Wins Minimum Prices,” IFAW, July 1946,

[100] “California CIO Council is Accused,” Seattle Times, August 8, 1946, 1.

[101] “IFAWA Fights Anti-Union Moves by Justice Dept.,” IFAW, August 1946, 25.

Pinsky, Fisheries of California, “CIO Resolution”, Unnumbered first page.

[102] Local 3 Executive Board, October 2, 1946, box 12, folder 11.

[103] “California Says ‘Do’ Anti-Trust Says ‘Don’t’ IFAW, January 1946, 33.