IFAWA collapsed in large part because of systematic prosecution that alleged it was a monopoly of businessmen, not a worker’s union. International Fishermen and Allied Worker , October 1946,

This essay is presented in five chapters.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Early Unionism in the Pacific Coast Fisheries

Chapter 3: A Coastwise, Industrial Union

Chapter 4: World War II

Chapter 5: Struggle, Strikes and Collapse

Leo Baunach's essay won the 2013 Library Research Award given by University of Washington Libraries.

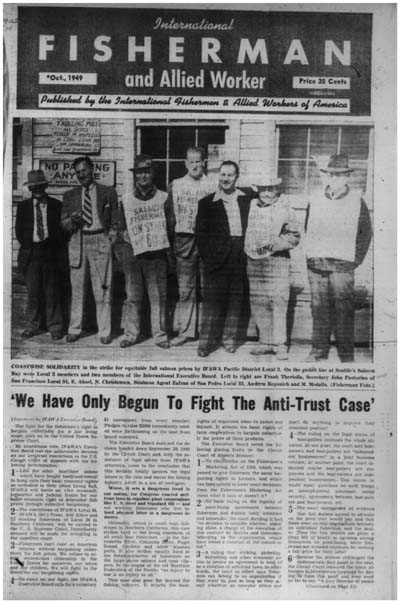

International Fishermen and Allied Worker, October 1949

by Leo Baunach

1946 saw one of the largest strike waves in the annals of the American labor movement, and business interests hit back beginning in 1947. Above and beyond the challenges facing other unions, and especially left-led ones amid the Red Scare, IFAWA had to contend with a systematic strategy of anti-trust suits that used their position as precarious workers to bust their union. At the same time that the federal government and the packers conspired against IFAWA, the CIO took a rightward turn and expelled it and ten other unions tied to the Communist Party.

This unique combination of attacks ended the International Fishermen and Allied Workers as a coastwise entity by 1952. Before this happened, however, IFAWA made some of its biggest gains and carried out its two most raucous and successful strikes. Puget Sound fishermen used picket lines for the first time in 1949 and held strong against the packers. The next year, an alliance of militant waterfront unions led by Alaska Native cannery workers in IFAWA smashed the regime of unequal pay for Native workers. Because of its rapid dissolution, history has forgotten IFAWA. This section completes an overview of the key role that fishermen and cannery workers played in the CIO and the post-war fight for economic justice.

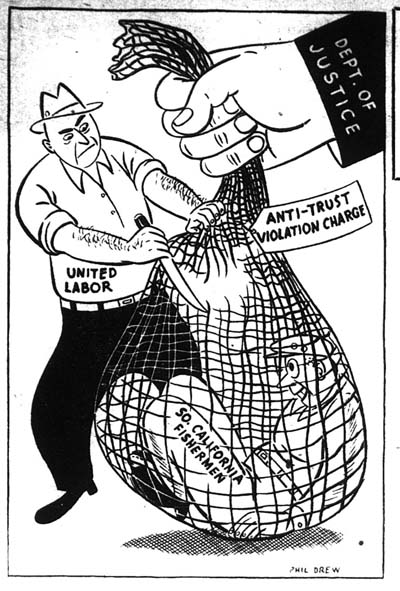

Reflecting on 1946, IFAWA leadership concluded that “At the close of the year we saw monopoly capital take over the driver’s seat from a fumbling Truman administration.”[1] Shortly thereafter, a grand jury in California initiated a trial of Local 36 officers on anti-trust charges. IFAWA’s lawyers mounted an impassioned defense, arguing fishermen were exempt from the Sherman anti-trust act because they sold their labor like any other worker. However, the officers of Local 36 were convicted in May 1947 and received $12,000 in fines.[2] IFAWA designed a multi-pronged strategy to appeal the decision and take the battle outside the courtroom. “Such an understanding of this so-called anti-trust case will enable us to mount an all-out counter-offensive,” the union wrote. “Once we see this attack for what it is – an attack on all workers – we will realize that we are not alone in fighting back. The millions of organized labor will join with us in moving through the higher courts, in going to Congress, and, above all, appealing to the people for a reversal of this unjust and vicious verdict.”[3] The situation worsened a month later when Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act. With a single stroke, union rights were curtailed and labor movement’s gains from 1930s were threatened. IFAWA explicitly linked the anti-trust attack with Taft-Hartley, identifying them as two parts of a broader assault.[4] The new law doubly threatened IFAWA. First, it excluded misclassified fishermen from using the National Labor Relations Board to defend their associational rights, which were reduced under Taft-Hartley. Secondly, it required union leaders to sign affidavits that they were not communists.

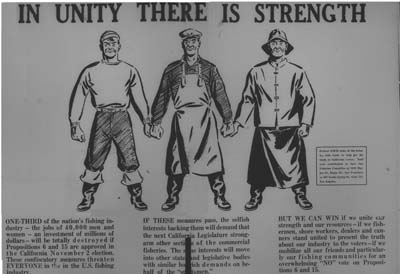

Meanwhile on Puget Sound, packers had stockpiled the previous year’s surplus catch in refrigeration facilities and overall consumer demand for fish was falling.[5] Together with Taft-Hartley, this allowed local packers to delay negotiations for the fall salmon season for six weeks after the date on which the two parties normally first met. To the south, the Columbia River Packers Association refused to sign any agreement.[6] These developments compounded a bitter internal fight over the merger of the large Local 3 (the former United Fishermen’s Union) and the smaller Local 53, representing Puget Sound Otter Trawl fishermen. The International had mandated a merger in the spirit of industrial unionism, but Local 53 fought hard against the move. They levied accusations of corruption against Local 3 Secretary-Treasurer Anton Susanj, and even threatened to add a company to a list of unfair products because it signed a contract with Local 3. Local 53 believed that the company fell under its jurisdiction.[7] In retaliation, Local 3 urged the International to revoke Local 53’s charter and charged that it included more captains and boat owners than workers, and even had small-time fish dealers as members.[8] In spite of this distracting fight, Local 3 continued to grow in size and represented 2,500 of the 4,000 fishermen in Puget Sound. This power became essential in 1947 when the union had to fight off an attack by non-professional sport fishermen, who launched a petition to make Puget Sound a recreational preserve in which purse seining would be banned. The move ruptured a longstanding alliance between commercial and sport fishermen, who had worked together against traps and pollution for more than a decade under the umbrella of the Salmon Conservation League.[9] The reasons for this move are unclear, but IFAWA identified it as a part of the wider reactionary turn, calling proponents of the seine ban “economic royalists, masquerading as sportsmen.”[10]

The International faced other problems. It cost $10,000 to appeal the ruling against Local 36, and the union established a Fishermen’s Freedom Fund to raise at least $50,000 for the anticipated court costs if the appeal moved forward.[11] They also launched an unsuccessful effort to convince the Department of the Interior, with whom they had a working relationship on regulatory issues, to lobby the Department of Justice to drop all anti-trust suits. With the Local 36 ruling, new cases were being brought in places like Northern California.[12] As with Local 3, it is important to contextualize these tough fights and setbacks within the growth and maturation of the union. In 1947, the union had 18,000 per capita members and an additional 7,000 workers upon which partial per capita was paid. This meant that IFAWA had an absolute minimum membership of 25,000 and was likely more than 30,000 strong because of continuing issues with per capita payments. At this time, there were about 42,000 fishermen on the Pacific Coast.[13] The number of shoreworkers is unclear, but in the 1940s there were usually equal numbers of fishermen and shoreworkers.[14] This means IFAWA may have exceeded 30% union density in the Pacific Coast fishery. This is a significant milestone in the US, where overall union density has never surpassed 30%.[15] Outside of the Pacific Coast, 600 members comprising five locals in North Carolina were been added, and a sizeable shrimp fishermen’s union in the Gulf Coast joined the CIO and was willing to affiliate with IFAWA.[16]

1948 began strong when Local 33 in San Pedro held its ground during a five week lockout and achieved a closed shop agreement.[17] In Puget Sound, the Northwest IFAWA Council was formed by Local 3 and other affiliates that represented reefnetters, gillnetters, otter trawlers, crab fishermen and shoreworkers.[18] Branches of the Alaska Fishermen’s Union in Bellingham and Seattle were later integrated.[19] The Council became an important point of encounter as relations with Puget Sound packers worsened. The most egregious situation faced crab fishermen, who faced rolling lockouts and sudden price. The workers responded with unity, and 90% of the crab fishing workforce regularly attended union meetings.[20] Meanwhile, the Alaska Fishermen’s Union achieved its highest ever price increase in negotiations with the Alaska Salmon Industry.[21] Local 3 also took tentative steps toward forming a gillnet division, after the IFAWA local representing these workers declined. A Gillnetter Organizing Committee was formed and a strike in Willapia Bay successfully reversed a price decrease.[22]

IFAWA held strong against attacks by packers, the federal government and ballot

initiatives to restrict commercial fishing

International Fishermen and Allied Worker, September 1948

The formation of the Northwest IFAWA Council was part of a wider strategy formulated at the January 1948 Convention to strengthen the union through joint councils and greater International involvement in negotiations. The ultimate goal was coastwise contract harmonization.[23] In March, a conference of Alaskan IFAWA affiliates was held and the Westward Area Fisheries Council (WAFC) was formed to cover the remote but high-fishing areas of the Alaskan Peninsula and Aleutian Islands. John Wiese, a member of the Cordova District Fishermen’s Union (formerly the Copper River and Prince William Sound Fishermen’s Union), became its energetic President and used a weekly radio broadcast to knit together the far-flung membership.[24] Originally from Northern California, where he was Secretary of the Shasta Tunnel and Construction Workers Union-CIO, he later moved to Seattle and worked as a reporter before moving into the fishing industry.[25] Lottie Edelman, an Alaska Fishermen’s Union Business Agent and working fisherwoman, became the Council’s Secretary.[26] The Council strove to “give the common people more voice in their fishery” and build democracy and respect for residents in the Territory. They also continued the longstanding IFAWA effort to ban traps in Alaska.[27]

In the political arena, IFAWA stuck to its principles in the face of increased repression of the left. The union strongly backed the campaign of Henry Wallace, a former Vice-President under Roosevelt who left the Democratic Party to run on the Progressive Party ticket. The International Executive Board, Local 3, Local 33 and various locals like Bellingham Cannery Workers Local 6 – in a unanimous vote at a membership meeting – endorsed Wallace.[28] In his written greeting to the January 1948 IFAWA Convention, Wallace went beyond boilerplate to discuss the anti-trust attack on IFAWA in great detail. [29] The same Convention took a strong stand against the Marshall Plan and Truman’s foreign policy.[30] There was isolated opposition, including the resignation of a longtime member in San Pedro who had been involved in wartime solidarity with Yugoslavia, but the union membership was largely behind the defiant program.[31] Additionally, the union backed the 1948 maritime and longshore strike that directly challenged Taft-Hartley. IFAWA gave food to strikers, donated to their strike fund and marched on the picket lines.[32] At the National CIO Convention in November 1948, Jurich joined the leaders of these same unions and other progressives to write the minority report opposing the National leadership’s support for Truman and his foreign policy, new limits of union autonomy and the investigation of Communist influence in CIO unions.[33]

As the Red Scare gathered steam, IFAWA was increasingly the target of these investigations. Leaders of the Cordova District Fishermen’s Union and John Wiese were brought before a travelling Congressional hearing held in Alaska on ‘Communist Infiltration of Maritime and Fisheries Unions.’ A former Secretary of the CDFU deftly sidestepped interrogation by saying “We have a lot of radicals – left wingers – who don’t like the way things are going, but Communists, never.”[34] On the anti-trust front, a fleeting victory came in July when a court ruling found that contracts with fishermen were valid, but master contracts were not.[35] The Local 36 case continued on appeal. The Freedom Fund had collected $54,000 in donations and voluntary assessments on top of dues, and an additional $8,000 from outside IFAWA, but legal costs had surpassed $75,000. The union had to withdraw funds from an organizing drive on the East Coast to cover the difference.[36] Complaints surfaced that fishermen in the collapsing sardine sector and cannery workers were being de-prioritized as resources became scarce.[37]

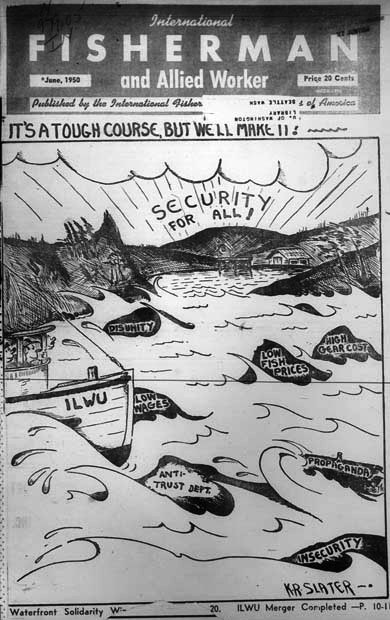

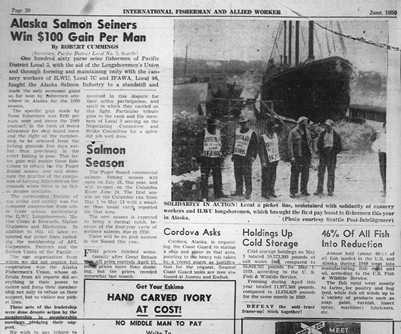

IFAWA merged with the International Longshore and Warehouse Union in 1950

after both were expelled from the CIO.

International Fishermen and Allied Worker, June 1950

At the 1949 IFAWA Convention, leadership proposed a merger with the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, arguing that a merger would provide more resources for the anti-trust fight. The officers noted that “The complexity and intensity of the struggles of the past year also revealed the basic shortcomings of IFAWA. More and more we saw that our organization lacks the facilities, resources, and personnel which are now essential to maintain the fighting trim, and to carry through successful battles.” [38] The union could adequately bargain, as seen by massive price increases that came with the lifting of price ceilings by Office of Price Administration, but leadership felt they lacked the research and public relations expertise.[39] The proposal for a merger with the ILWU was not a new one. It was first floated in 1946 as an alternative to the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers and the San Francisco IFAWA local had symbolically proposed it every year since.[40] ILWU Vice-President Louis Goldblatt attended the 1949 Convention, answering questions about local autonomy and the integration of IFAWA as a division with equal standing to the longshore and warehouse sections. The delegates seemed satisfied with these answers, and the recent organizing of Hawaiian sugarcane workers into the ILWU provided an example of diversification outside shipping.[41]

Once the proposal was on the Convention floor, however, the Alaska Fishermen’s Union (AFU) delegation came out against it. They argued that not enough time had been provided to consider the idea since its initial proposal in December 1948. AFU delegates, including IFAWA Vice-President Oscar Anderson, voted against the idea. Goldblatt and the ILWU delegates withdrew the merger proposal for fear of causing a split in IFAWA. Later in the Convention, Anderson and another Alaska Fishermen’s Union delegate announced they were switching their votes to ‘yes,’ and a resolution was passed recommending a merger and asking affiliates to conduct internal balloting on the idea.[42] As the process began, the major sticking point became per capita payments. Many affiliates, especially small, direct locals were concerned that a merger would mean increased dues obligations, and the possibility of having to pay a full year’s per capita to the ILWU on seasonal members. Despite repeated assurances to the contrary, the concerns were never fully allayed.[43] However, there was openness to the idea because of the longstanding closeness between longshore and fishing workers.[44]

Throughout the International, there was a recognition that a go-it-alone attitude that treated IFAWA as a federation rather than a union would no longer suffice. The Convention formulated a strategy that asked locals to form joint negotiation committees with other IFAWA affiliates and mobilize for each other’s demands.[45] In 1949 the Northwest IFAWA Council continued to thrive, but the Westward Areas Fisheries Council and a Northern California Council were the only other coordinating bodies that had been formed. In Puget Sound and Alaska, a breakthrough on joint action came in March when representatives of IFAWA and the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers, including John Wiese, President Jurich and FTA Regional Director Bob Kinney met to discuss upcoming cannery negotiations with the Alaska Salmon Industry (ASI). In a notable meeting, the two unions resolved outstanding questioning of jurisdiction, agreed to joint negotiations with the ASI and decided to demand full wage parity for resident and non-resident workers. They also formulated a plan to engage in an unfair labor practice strikes if necessary, in spite of the no-strike clause in the existing ASI contract. [46] IFAWA Local 46 President Joe Nashoalook, representing Alaska Native cannery workers in Bristol Bay, became a member of the International Executive Board in 1949 and was an active participant in union business, travelling to Washington, D.C. on a legislative trip and garnering a great deal of support among the rank and file.[47] A hard-line stance by the Alaska Salmon Industry again prevented full wage parity, but the two unions preserved their unity throughout negotiations.[48]

During the 1949 strike, fishermen picketed in the Puget Sound for the first time.

University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections,

Local 3 Records, Accession #3466-001, box 11, folder 16

The biggest battle of 1949 took place in Puget Sound, where salmon fishermen went on strike in fall. Numerous work stoppages called ‘tie-ups’ have been omitted from this essay because they were usually short and taken against a specific cannery or company. In 1949, fishermen moved beyond the passive tie-up tactic, a mobilization-free withdrawal of labor, to directly confront and picket the packers. Puget Sound negotiations began in spring with the herring fishermen, who rejected a series of ‘last, best and final’ offers from the packers between March and June, even when it became clear that continuing to rebuff the them would mean no herring season that year. Ultimately, only 125 of the 500 herring fishermen were dispatched that year after a limited deal was reached for late-season operations in Alaska.[49]

At the time, there were two separate salmon fishing seasons, one from late July until September, and another in October and November. In June and July, salmon fishermen, tendermen and cannery workers voted down proposals from the packers for 18 cents per pound for sockeye salmon and 8 cents per pound for pink salmon. On the opening day of the fishing season, July 19th, fishermen stayed home. They wanted 25 cents per pound for sockeyes and 12 cents for pinks, not the 20 cents and 10 cents now offered by the packers. The Department of Labor’s Conciliation Service intervened on July 21st, but a reduced union offer after mediation of was rejected by the packers. On July 25th, mayors around Puget Sound were on the verge of holding a summit on the situation when Local 3 and Local 4, representing reefnetters, voted to accept the 20 cent, 10 cent formula. This meant no gains for fishermen, but tendermen staved off an attack on their vacation time, expanded the definition of overtime, and gained raises. Additionally, the packer’s offer for cannery workers contained favorable vacation time accrual and a five cent hourly raise across all job classifications.[50] The offer for tendermen and cannery workers was given by the packers on July 24th, and the fishermen likely looked at the broader picture of the membership and compromised. Elsewhere during July, there was 23 day tie-up on the Columbia River and a short joint strike by the Alaska Fishermen’s Union and the Cordova District Fishermen’s Union against the Alaska Salmon Industry.[51]

As the summer Puget Sound salmon season began to wind down in early September, negotiations for fall began in earnest. The packers wanted floor prices of 8 cents for chum salmon and 15 cents for silvers, with some offering a verbal promise to set opening prices two cents higher than the floor. The prior year, they had agreed to 18 cents for chums and 23 cents for silvers, and the union refused to accept a decrease of more than 22%. In turn, the packers rejected a union proposal that would put canned salmon and fresh salmon prices on separate tracks. Companies that operated in both markets, like the Washington Fish and Oyster Co., Whiz Fish Co., and the Fishermen’s Packing Corporation insisted that the price be uniform and that they retain decision-making over how to process and sell the fish they bought. To pressure the union, they leveraged a declining price for canned salmon and the devaluation of Canadian currency, which made imports from British Columbia cheaper. They also claimed that Puget Sound canneries could continue to function in the case of a strike by processing Alaskan fish from large freezer ships and taking on product from Southeast Alaska, where no canneries were operational for the season. [52] By October 3rd, it was clear that the packers would not make a new offer, and Local 3 began strike preparations. Emergency meetings were held that night and a strike notification went out to all members the next day. A plan was made to completely shut down the operations of Puget Sound canneries by preventing any tender or fishing boat from unloading. Picket committees were formed in Seattle, Tacoma, Gig Harbor, Everett, Anacortes and Bellingham, and deployed at 4am on October 5th.[53]

It was the first time IFAWA fishermen had launched an all-out strike, what they called a strike on an “industrial basis.”[54] The strategy of attempting to prevent the delivery of any fish was also a new one. As the pickets began, Jurich asked members of the Alaska Fishermen’s Union to not deliver to Puget Sound ports and contacted British Columbia fishermen, who had consolidated in the United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union (UFAWU). Now, the failure to build a cross-border union came back to haunt Local 3. The idea of unification had been discussed from time to time, including at the 1948 Convention, but was always preempted by more pressing concerns.[55] The short shipping distance and an exchange rate that favored American businesses made Canadian fish most serious threat to the strike. Had UFAWU and IFAWA been united, Canadian fishermen may have been able to extend a short strike that they had held in September until the Puget Sound negotiations were settled.

Despite the looming threat of imports breaking the strike, the pickets met early success and the strike was observed by the over 2,000 members of Local 3. This idled 200 purse seine boats along with gillnet boats and other salmon-catching vessels.[56] The adhesion to the strike was remarkable given that it meant risking an entire season of work. Additionally, no strike benefits were paid unless a member pled hardship in front of a review board. Fishermen were strongly asked not to seek out other employment during the strike, and would have 10% of their earnings fined after the strike if they failed to appear before a review board to justify their choice. Notions of solidarity and the hope that a short-term loss would mean long-term income gains were important, but the heavy penalties established by the union likely played a role. Failure to do picket line duty was a $50 fine, and various fines were established for other failures to comply with union orders. For example, a boat that failed to send a representative to a mandatory emergency meeting was prevented from fishing for two days if and when operations resumed and had to appear before a trial committee.[57] At the time, average yearly income for American workers was only two or three thousand dollars, meaning $50 was over a week’s worth of income and compounded the financial losses from being on strike.[58] Fishermen earned much of their yearly income during the short seasons, meaning a strike was even more difficult than it was for hourly workers. Outright opposition to the strike, like one member that accosted a picket line and accused the leadership of being communists, meant likely expulsion from the union.[59] Expulsion barred a fisherman from delivering to any cannery that had closed shop agreement with Local 3 or being cleared to work on any union boat. These tough penalties make it difficult to gauge how many members observed the strike because of union loyalty and how many decided that it was easier to do so than face steep fines and the loss of access to fishing jobs. On the other hand, during the July dispute over 1,000 members directly voted on a contract offer, and in the midst of the fall strike, more than 500 members voted on the on the content of the proposal that the union would make during a bargaining session.[60] That a full quarter of a union would participate in crafting a bargaining proposal – which even if accepted by the packers could be overturned in a contract vote – indicates a high level of participation, democracy and member investment in the union.

On October 10th, the packers offered 20 cents for silvers and 10 cents for chums, but were again voted down by the membership.[61] The primary message of the workers was simple: “We strike only for a living wage. We fishermen are the best conservationists, because we want to protect our source of livelihood. The high price you pay for salmon is due to profiteering by packers and middlemen.” As the strike gathered steam after October 5th, they increasingly sought to expand their message beyond prices and make it an action against the misclassification of fishermen and the importation of cheap foreign fish. [62] Local 3 Secretary-Treasurer Bob Cummings stated in an October 17th interview that “We’ve got two objectives in mind right now. First, of course, is to get a decent contract and get the boats out fishing. All we are asking is a decent wage so we can make a living. The second objective is to fight with every weapon at hand against the importation of Canadian fish.”[63] They were careful to express their solidarity with Canadian fishermen, who received only a fraction of the profit made by the packers, but were vitriolic in their opposition to imports.

Beginning on October 15th, the union began to settle with small fresh fish dealers and smaller, independent processing facilities that normally did not buy from purse seine vessels. This allowed gillnetters to return to work, receiving 14.5 cents for chums and 20.5 cents for silvers. Local 3 pledged to dispatch fishermen for any company that agreed to the same price. They also invoked a clause in the previous contract about prior warning of cannery shutdowns, promising to lift pickets on a plant if the company legally promised to cease operations for the duration of the season. [64] The reopening of small facilities created an option to divert Alaskan and Canadian fish if such product was brought to the Sound. This was particularly important because the threat of injunctions forced Local 3 to back off its attempt to block all deliveries. At an October 17th meeting, Local 3 Secretary-Treasurer Bob Cummings noted that “We can’t picket fish. The fish cannot be declared unfair unless it is caught or processed by scab workers behind our picket lines. No fish that has yet come in can be declared unfair or ‘hot.’” The union re-framed its pickets as informational attempts to convince cannery workers not to process fish, and under injunction agreed not to block any deliveries of fish caught outside the Sound.[65] Union leaders claimed there was widespread sympathy among AFL cannery workers. This was borne out in Anacortes, where AFL workers finished processing frozen salmon from Alaska delivered before the strike and then walked off the job.[66]

Beginning on October 20th, the united front of packers began to crumble. More and larger companies began to accept the price offered by the union, and the rate of such cave-ins accelerated.[67] On the 25th, some of the biggest packers offered a deal. They agreed to the two-track system, with 10 per pound paid for chums that would be canned, 12 cents for chum that would be sold fresh, and 20 cents across the board for silvers. By now, the runs of silvers had declined to a point where the latter offer was largely moot.[68] The offer was rejected and the union held strong to its demand for 14 cents for chums. Meanwhile, an agreement covering all fresh fish dealers was reached at this price. This returned 25 boats to work, adding to the 50 that had already been cleared to fish for smaller dealers and canneries.[69] By early November, only some big packers including Whiz Fish Co., Washington Fish and Oyster Co., Sebastian-Stuart Fish Co., and Farwest still refused to settle. Other major companies like Booth Fisheries, and San Juan Fishing & Packing Co. had already capitulated.[70] For many in Local 3, the strike continued until the scheduled end of the season on November 20th, although the intensity of picketing and other activities subsided after November 1st.

All-out mobilization by cannery workers, fishermen and longshoremen defeated the

Alaska Salmon Industry in 1950. International Fishermen and Allied Worker, June 1950

All in all, the strike was a victory. The fishery workers were not unnerved by the possibility that their strike and their union could be broken by imports or companies that would rather lose a season’s worth of profits than capitulate. The structure of salmon purse seining on the Puget Sound, in which most boats were owned by third parties and not fishermen or packers, insulated Local 3 from anti-trust threats but the specter of Taft-Hartley hung in the background. Despite this, IFAWA broke any semblance of unity among the packers. Of equal importance, the strike cemented unity within Local 3 between fishermen and cannery workers, and between fishermen in different gears. This shared struggle and experience was imperative if the union was to withstand the many challenges it faced. Around this time, Local 3 was at the height of its membership with 2,269 total members, up from around 1,700 in 1946.[71]

At other points in the history of IFAWA, the Local 3 strike would have been the most important event to take place on the Coast. However, there was no time to savor the victory. The December 1949 Conference of Local 3 learned that the National CIO was moving to expel IFAWA and barely discussed the strike.[72] Though angered by the CIO’s actions, many felt that it was better to stay inside the federation and fight the charges than leave and be exposed to raiding by other CIO unions. The threat of raiding brought the merger proposal to the fore once again. The deadline for internal referendums on amalgamation with the Longshore and Warehouse Union was repeatedly extended and it was finally settled that ballots would be completed by the January 1950 Convention. Several locals were plagued by low participation. In Local 3 just 500 members turned in ballots and an additional round of voting only increased the total vote in the Local to 838.[73] This contrasted with the high levels of participation in strike meetings and votes.

The Convention in 1950 came at an extremely tough time for the union. The Circuit Court of Appeals ruled on the Local 36 case and set a strong precedent against any strike, picket or boycott activity by fishermen. The only remaining option was to appeal to the Supreme Court and argue that the Fishermen’s Collective Marketing Act of 1934 protected associational rights. It was not a particularly good option; the Act concerned cooperatives and did not have any explicit language related to unionism. It was pursued nonetheless.[74] The case continued to drain the union’s finances, and IFAWA was now $12,000 in debt over the case. Funding was withdrawn from the Westward Areas Fisheries Council and a staff position in Northern California eliminated.[75] Frustration ran high at the Convention, especially over the question of the merger. The membership of several small locals and the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union had voted internally against the idea. The opposition was known before the gathering, so the International leadership carefully crafted a proposal that called for increased cooperation with the ILWU and left the door open to a merger, but did not effectuate one.[76] The Alaska Fishermen’s Union was increasingly discontented and clashed with delegates from other affiliates.[77] Tensions on the floor reached a boiling point when Matt Batinovich, the original President of the Federated Fishermen’s Council, launched an attack on Kibre and Jurich for dereliction of duty. He claimed that they had prioritized good relations with packers like Nick Bez over worker interests, and had restrained a crew from engaging in a work stoppage.[78] Nevertheless, even Batinovich ardently opposed the National CIO and returned to the fold to strategize about the looming expulsion.[79]

Not long after the Convention, Oscar Anderson of the Alaska Fishermen’s Union resigned as IFAWA Vice-President and encouraged his union to leave the International. Abe Lehto, a pro-IFAWA member of the Alaska Fishermen’s Union, replaced him as International Vice-President.[80] With a trial of the union by the National CIO scheduled for late May, the International leadership renewed their efforts to merge with the ILWU, which was also pushed out of the CIO.[81] The trial ended as expected with IFAWA’s expulsion.[82] Immediately afterwards, a unanimous vote was taken by the Executive Board to merge with the ILWU under the resolution passed at the January 1950 convention. Meanwhile, elements in the Alaska Fishermen’s Union moved for an internal referendum on disaffiliation.

The merger came at a fortuitous time. The Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers, similarly expelled from the CIO, had already joined the ILWU. This put Local 46 members, who composed half the Bristol Bay cannery workforce, under the same roof as the non-resident cannery workers now in ILWU Local 7-C.[83] The two locals signed a pact to not settle until both had agreeable contract offers and Local 46 President Joe Nashaolook travelled to Seattle on May 3rd to negotiate alongside Local 7-C leaders like Ernesto Mangaoang.[84] After the Alaska Salmon Industry refused to negotiate with or recognize Local 7-C and attempted to sign a contract with the National CIO’s Packinghouse union, 7-C refused to dispatch members to Alaska and on May 10th set up picket lines at facilities owned by ASI companies around Puget Sound.[85] Local 46, Local 3 and the pro-IFAWA faction of the Alaska Fishermen’s Union backed the action and attended the Puget Sound pickets.[86] International Secretary-Treasurer Jeff Kibre enthusiastically declared “Unity of resident and nonresident on a common beef – with united support! For the first time we have mobilized the fighting strength of the organizations that have a stake in Alaska, and what has happened – Industry is screaming!” He continued, arguing that “In this struggle is contained a program for Alaska; victory in this beef is going to be the signal to the people in the Territory, and the rank and file of AFU to get behind the correct program.”[87] In a bizarre incident, Nashoalook was deceived into signing what he believed to be a mutual aid pact with the AFU. Instead, it was a pledge to align Local 46 with the AFU splitters, and the alleged defection of Nashoalook made headlines across Seattle before he could disavow the rumor.[88] Picketing continued until May 30th when the ASI filed a successful injunction arguing Local 7-C was conducting a secondary boycott by preventing shipments of cannery equipment from leaving Puget Sound.[89] Taft-Hartley severely limited secondary boycotts, in which a third-party to a labor dispute – shipping vessels in this case – is targeted in order to exert pressure on the employer.

The limits of Taft-Hartley and the intransigence of the Alaska Salmon Industry were overcome by a precisely coordinated show of solidarity. Around May 25th, Local 3 went on strike and voted 3-1 to not sign a contract with the ASI until the non-resident and resident cannery workers had settled.[90] On May 30th, joint conference of the three ILWU units – Local 3, Local 46 and Local 7-C – was held and Nashoalook was elected its chair and representative to the ASI.[91] Out of this committee came a militant united front of the three fishing industry units of the ILWU, and their demand for joint negotiations and settlement with the ASI for all gained the support of five additional unions that represented smaller groups workers.[92] An IFAWA statement declared that “the time has now come to re-establish on the West Coast the same powerful maritime unity which enabled fishermen, longshoremen, seamen and allied workers to mobilize their ranks in the 1930’s and wrest from the employers decent wages and conditions.”[93] Adding to the pressure, ILWU longshore members in Alaska pledged not to unload any cannery equipment until the strike was over.[94] Local 46 was prepared to send members to Puget Sound to picket if Local 7-C was prevented from doing so by an injunction. The ILWU also carried out solidarity and secondary actions by picketing canneries in Bellingham and the Columbia River that were owned by ASI companies.[95] Meanwhile, IFAWA held strong against a threat by the employers to fire the 160 members of Local 3 that worked for the ASI if a contract was not immediately signed.[96]

The kind of action-oriented solidarity and cross-shop joint action has rarely been seen in the American labor movement. Faced with overwhelming unity and the paralysis of its operations, the Alaska Salmon Industry capitulated just days after the injunction against Local 7-C pickets. Cannery worker contracts were signed on the fifth of June and Local 3 fishermen ratified a contract three days later with a $100 pay increase.[97] Jerry Tyler, labor activist and Seattle radio host concluded that “when the ILWU, with its record of fighting and winning for the people of Hawaii, who got the same kind of a going over from the Big Five in the Islands as Joe’s people got from the Alaska Salmon Industry,” entered the picture, workers flocked to it and won the strike.[98]

For Local 46, the gains were nothing short of incredible. At long last, they were given full pay equity with nonresident workers. They also gained the right to overtime pay, which had previously been denied because all hours worked were counted toward the fulfillment of the guaranteed seasonal income established in contracts, no matter how long the shift or the total hours worked in a week. In 1949, the ASI had hired resident workers for 15 minute shifts during pre-season, and then laid them off once the season began in favor of nonresident workers, leaving them with almost no pay. The new collective bargaining agreement gave a minimum of two hours worth of pay per shift and raised the guaranteed seasonal minimum by $100-150, depending upon classification. It also ensured that resident workers got equal opportunity for work and promised 40 hours of pre-season work that would not count toward their seasonal guaranteed earnings.[99] The effectiveness of the united front in achieving these gains makes clear why Taft-Hartley criminalized secondary boycotts and other industrial actions that concretely express support for workers in another shop.

Once again, IFAWA was reaching the heights of its power and success just as the earth was eroding beneath its feet. In a crushing bit of irony, the extended time that Nashoalook had to spend negotiating in Seattle allowed the National CIO to set up a splinter ‘Industrial Union Local 46’. It was a hollow ploy that installed the owner of a store as the head of the new local, but nevertheless forced IFAWA to seek a court order halting negotiations between the National CIO’s Local 46 and the Alaska Salmon Industry.[100] Ultimately, the National CIO and IFAWA were fighting over a rank and file that lost interest.[101] The Bering Sea Fishermen’s Union (BSFU), a branch of the Alaska Fishermen’s Union made up of mostly Native residents, utilized the chaotic situation inside the AFU to leave it after years of strained relationships with non-resident fishermen.[102] The Bearing Sea Fishermen’s Union affiliated with the AFL and waged a vicious fight for recognition in 1951, striking the first part of the summer season. The resident cannery workers, who came from the same communities and families as the BSFU members, petitioned for AFL affiliation and joined the strike. It ended in early July with a 25 cent per hour wage increase for resident cannery workers.[103] The same kind of solidarity that won the 1950 strike now undermined IFAWA’s presence when fisherman-cannery worker solidarity meant leaving Local 46.[104]

IFAWA had the potential to replicate the kind of social, economic and political transformation initiated by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union in Hawaii, especially if it had been able to maintain control of the sometimes domineering non-resident leadership of the Alaska Fishermen’s Union. Like the pre-statehood Hawaiian sugarcane and agricultural workers that organized under the banner of the ILWU, fishermen and cannery workers occupied a strategic position in the territorial economy. Alaska was dominated politically and economically dominated by big business, particularly companies like those in the ASI that were based in Seattle and took advantage of the territorial status of Alaska to make easy profits.[105] In Hawaii, the ILWU’s democratic, people of color led unionism unseated the domination of the island by a ‘Big Five’ group of corporations and their allies in the white Republican Party machine.[106] However, IFAWA always had to answer to the AFU, which comprised a third to a half of its membership, and was crippled by the withdrawal of a large section of the non-resident union following the ILWU merger.

Running out of options, IFAWA attempted to enshrine employee status in contracts

with packers. International Fishermen and Allied Worker, September 1950

The union was in peril and launched several last ditch efforts. The Supreme Court denied Local 36 a hearing, and the anti-trust attack expanded with a grand jury investigation of Local 33, the other main IFAWA unit in Southern California.[107] Local 33 gained some reprieve when its trial was delayed until June 1951, giving IFAWA time to integrate into the ILWU and, more importantly, make structural changes that would stave off further anti-trust suits.[108] A Fishermen and Allied Workers Division (FAWD) was set up in the ILWU to replace IFAWA, and an aggressive push was made to gain contract clauses that recognized fishermen as direct employees.[109] Additionally, the union filed a counter-suit alleging monopoly practices and price collusion by packers, and tried to use the consolidated structure of the Fishermen and Allied Workers Division to finally institute coastwise bargaining.[110] As occurred throughout the history of fishermen’s union, this was preempted by more pressing concerns. Local 3 was in an intense battle with the National CIO over Washington State cannery workers, and Southern California was the target of renewed raiding by the AFL Seafarer’s Union.[111] Jerry Tyler, the former Secretary of the Seattle Industrial Union Council, was hired to coordinate a campaign to win cannery worker representation elections from Blaine to the Columbia River. He was able to turn the tide in Bellingham and La Conner, where workers had initially opted for the National CIO, and won another election covering most canneries in Anacortes and Blain despite spending just $3,000 in comparison the National CIO’s $12,000.[112] However, the ILWU fishermen lost an election to represent cannery workers at plants owned Pacific American Fisheries, one of the largest packers on the Sound.[113] In February 1951, the fishermen’s union was routed 789-291 in an election to represent Columbia River cannery workers.[114] The Fishermen and Allied Workers Division (FAWD) continued to fight for control of the Alaska Fishermen’s Union and convened a meeting of 300 Seattle members who voted in October 1950 to join the ILWU. A smaller number of AFU members in San Francisco supported the ILWU but there was no support among the membership in Bellingham, the headquarters of the Alaska Fishermen.[115]

Meanwhile, Local 3 developed another creative job action when negotiations stalled, reversing preparations of gear and removing painstakingly loaded nets from boats.[116] Isolated success was made on toward contractually enshrining an employer-employee relationship by drag boat fishermen in San Francisco, who went on strike in February 1951 demanding classification as piece-rate workers.[117] The packers reversed an initial promise to jointly ask for a favorable legal opinion on the new contract, and instead asked a US Federal Court to bar any such language.[118] The setbacks were mounting for the ex-International Fishermen and Allied Workers. Publication of the Fishermen and Allied Worker ceased in March 1951, and as membership shrank the decision was made to gradually eliminate the Fishermen and Allied Workers Division and replace it with a caucus.[119] The initial plan to shift staffing of the Division to Jeff Kibre in San Francisco, with Jurich staying on in a reduced role as Chairman, was scrapped and Kibre became the ILWU representative in Washington, D.C. He held the position until his death in 1967.[120] Membership in the Fishermen and Allied Workers Division remained at 16,000, but heavy losses among the ex-IFAWA were masked by the absorption of FTA fish cannery locals.[121] A pitched internal battle took place within the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union in 1950, as union leadership decided to join the ILWU despite a majority ‘no’ vote in an internal referendum. Both the Columbia River Packers Association and the National CIO filed injunctions to force a representation election, which the CRFPU refused to do until its executive board was threatened with criminal proceedings.[122] It held the mandated election, but never revealed the results and burned the ballots before holding another union-administered election in July.[123] A positive result temporarily kept it in the ILWU, but in 1951 the CRFPU decided to go independent.[124]

The remnants of IFAWA in the ILWU experienced a slow decline after the losses of 1951 removed its ability to convert a coastwise critical mass of workers into power at the bargaining table and on the picket line. On the Puget Sound, Local 3 attempted to obtain direct employment clauses in their 1952 negotiations with the Puget Sound packers and the Alaska Salmon Industry. Both refused but continued to negotiate price agreements with the union.[125] In the place of a division, all ILWU fishermen became part of a coastwise Local 3, and Puget Sound became Local 3-3. The area was the strongest part of the new mega-local but was still forced to accept major concession in 1953 negotiations.[126] In 1954, the Federal Trade Commission issued an order blocking Local 3-3 from negotiating price agreements, though the union was able to evade compliance for at least a year.[127] A strong cadre of leadership forged in the 1949 strike remained in place, and Jurich returned as Secretary-Treasurer in 1955 after a few years in a reduced role.[128] Although Local 3-3 could no longer negotiate over prices, it continued to negotiate with vessel owners over working conditions. The Local also continued to represent tendermen and cannery workers.[129] Meanwhile, fishermen were beginning to be squeezed from both ends by legal and environmental factors. In 1957, Puget Sound salmon fishing was restricted to three days a week, and the next year the number of boats fishing salmon declined from 39 to 15.[130] Members were now updated by a one-page, double sided monthly mimeographed newsletter, a far cry from the old union paper. In 1958, Puget Sound purse seiners launched a brief strike. It failed to rekindle fishery worker unionism on the Sound.[131] A few years later, the Boldt decision handed half of the Puget Sound catch back to Indian peoples.

While British Columbia had taken longer to consolidate into an industrial union, the Canadian United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union (UFAWU) was able to outlive its American counterpart. They too struggled with red baiting and anti-trust laws, and spent two decades outside the main federation of Canadian unions. However, UFAWU stayed united and grew from 4,000 to 7,000 members during the 1950s. When the packers refused to negotiate in 1959, UFAWU launched a twelve day general strike of all fishing and cannery members. The pressure exerted during the general strike and the several years of industrial conflict that led up to it – twenty-five strikes occurred between 1945 and 1963 – forced the government to write laws which protected the collective bargaining right of fishermen, albeit weakly as ‘dependent’ contractors.[132] UFAWU’s strategy of high stakes escalation did not end there. The most dramatic episode came in 1967, when the union refused to comply with an injunction ordering shoreworkers back to work. UFAWU’s Secretary, longtime Communist Party activist and fisherman Homer Stevens, and the union’s President spent a year in jail and UFAWU paid $25,000 in fines. The membership overwhelmingly reelected its officers while they were still incarcerated.[133] Today, UFAWU is part of the militant Canadian Autoworkers in a division that unites it with fishermen on country’s East Coast.[134]

Across the border, Local 3-3 was a servicing local with no organizing capacity.[135] It was administered existing agreements but was incapable of contract campaigns to mobilize the membership during bargaining. A broad membership continued, including salmon seine and herring fishermen in Puget Sound and Alaska, tendermen in Puget Sound, and crab fishermen and some processing boat workers in Alaska. Jurich was a competent and committed staffer, but the movement atmosphere of the 1930s and 1940s had disappeared. Over time, the constitution of the union was altered to decrease the frequency of meetings and elections.[136] The economic decline of the West Coast commercial fishing and canning industry, and the Puget Sound industry in particular, began in earnest with the 1966 dissolution of Pacific American Fisheries.[137] Raids by the Alaska Fishermen’s Union and the Seafarer’s Union became ever more costly as the workforce shrunk in size.[138] By this time, there is no evidence of ILWU fishermen’s units outside of Puget Sound, and Local 3-3 reverted back to being called Local 3. Jurich stayed on at the Local until retiring in 1978 or 1979. In 1984, he passed away at 83.[139] The union effectively died with him. A new Secretary-Treasurer took his place, but shuttered the Local office in Seattle in favor of a PO Box.[140] Local 3 became barely functional and failed to follow through on its end of a joint organizing project with ILWU Local 37, the former ILWU 7-C, which was undergoing a period of reform and renewal. No cannery workers were left on Puget Sound, and one of the final contracts signed by Local 3 covered handful of caretakers and security guards at a Blaine cannery for 1980-1982.[141] The Local soon fell into arrears on its per capita payments to the International. In January 1982, Local 3 was unceremoniously declared defunct by ILWU Executive Board and quietly ceased to exist.[142] Many organizations of fishermen exist, usually marketing associations. The Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union, the first fishing union on the West Coast, continues to exist without a collective bargaining role but may soon see the end of gillnetting on the River. A few crab fishermen in California have kept the strike alive, but they are the exception in an industry that has dramatically changed since the 1950s with ecological decline and regulatory change.[143]

Conclusion

Fishery worker unionism as coastwise working-class movement ended thirty years before 1982. Among the eleven unions expelled from the CIO, only the ILWU and the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE) survive. Bitter factionalism, union-busting, red-baiting and raids destroyed the other unions. On top of these problems, the International Fishermen and Allied Workers faced a systematic effort by the state to dismantle their union. From the very beginning of its existence, anti-trust cases attacked the associational rights of fishermen. In the post-war period the state upped the ante and criminalized union participation. The dismemberment of IFAWA was a direct outgrowth of this unrelenting utilization of the legal system to prosecute and bankrupt affiliates of the union. This was carried out in concert with the packers, and at its height the anti-trust push allowed companies to defy a union with whom they had bargained for over a decade. IFAWA did not back down and won key victories in 1949 and 1950, but the costs of the anti-trust cases and expulsion from the CIO proved too costly for the morale and finances of the union to the union’s finances and morale in combination with the withdrawal of support by the CIO proved overwhelming. In its short existence, IFAWA transformed the industry and made significant progress in rectifying the precarious nature of work in fishing and processing. In 1950, fishermen and shoreworkers had guarantees about their seasonal income, work and safety rules and a myriad of other contract gains. It was a far cry from the price chaos and instability of the early 1930s.

‘Precarious employment’ connotes two circumstances. The first is an employment relationship that is unstable and exploitative – seasonal, misclassified, (permanently) temporary, informal, subject to arbitrary dismissal – and the second is the precariousness of everyday existence in jobs where safety standards are nonexistent and a social safety net is nowhere to be seen. Fishermen and shoreworkers in the 1930s embodied both meanings, and IFAWA confronted these conditions head-on by through collective bargaining and political action that demanded inclusion in social programs. Perceptive organizing methods that fitted to the unique aspects of the industry and community networks that stretched from San Diego to Bristol Bay united workers who had been divided by geography, ethnicity, craft and disparate employment relationships. They did so in the CIO era, which is remembered and misremembered as a pre-neoliberal heyday of regular employment and the welfare state. This essay complicates this narrative and highlights the long arc of precarious work, which has always been a reality for women, immigrants, and other hyper-exploited sectors of the working class.[144]

By drawing on unused and rare records, I hope to give a forgotten union a place in the history of the CIO and the West Coast waterfront. Much of the attention has rightfully been on the ILWU, and IFAWA was closely connected to the formidable union. However, a more complete version of the radical and militant West Coast ports of the CIO era includes smaller but no less important groups like the National Union of Marine Cooks and Stewards and the Fishermen and Allied Workers. These overlapping communities built off each other’s power, as shown by the intertwining of strikes in Southern California by an IFAWA forerunner with the 1934 longshore strike. The trajectory of the Fishermen and Allied Workers between the mid 1930s and 1951 is emblematic of the overall history of CIO, showcasing how industrial unionism reached new sectors of workers, the sacrifice by labor to win the war, and the damage done by the internal political fights of the late 1940s.

Additionally, the anti-trust cases and unique multiethnic and gender dynamics of the union add to discussions on the labor and the state, and ethnicity, civil rights and gender the vibrant labor movement of the 1930s and 1940s. This essay identifies two groups who are rarely studied in relation to class and labor, Yugoslavian immigrants and Alaska Natives, as the bedrock of IFAWA. The involvement of Alaska Natives led the union to enact civil rights unionism through a fight for pay equity, in spite of the recurring limits imposed by the mostly non-resident Alaska Fishermen’s Union. It is interesting to note that the only evidence I can find of IFAWA ending pay inequality for women was also in Bristol Bay. The alliance of resident Alaska Native and non-resident Asian-American cannery workers merits attention as an example of multiracial unionism with anti-colonial implications. IFAWA also provides another look at the Communist Party’s complex role in labor organizing. Party organizers introduced industrial unionism and transformed halting collective action along craft lines into a sustainable coastwise organization. This essay demonstrates how leftist leadership remained connected with the rank and file through a common interest in transnational solidarity and through the intersection of material and ideological concerns. Finally, the experiences of IFAWA and its forerunners challenge notions of fishermen as individualistic pioneers or businessmen separate from the working class.

Research for this piece began shortly after misclassified port truckers in Seattle led a groundbreaking two week wildcat strike supported by the Teamsters and the Change to Win federation, and concluded shortly before supposedly independent port truckers in LA/Long Beach signed a landmark contract with Toll Group. Despite these important campaigns, misclassified workers remain outside of the labor movement and are rarely on the agenda of organized labor. Meanwhile, unions are struggling to find the tools to organize the unorganized in an era in which precarious work impacts all sectors of the working class. The experience of the International Fishermen and Allied Workers is a neglected historical example that offers important lessons and warnings for this effort. Its analysis was simple and actionable: fishermen and shoreworkers, regardless of their official employment status, produced profit for the packers and only a single union that covered the entire Coast and workers at all stages of production could reclaim their rightful share.

[1] Report of Officers, 8th IFAWA Convention, January 21-24, 1947, box 11, folder 17.

[2] “Fishermen Convicted as “Monopolists,’” IFAW, May 1947, pages 1 & 3; Local 3 Executive Board May 10, 1947, box 12, folder 8; Pinsky, The Fishermen of California; Robert Kenny, “The Battle of America’s Primary Producers,” IFAW, June 1947, 1.

[3] ““Message to the Membership on the Anti-Trust Case,” IFAW, June 1947, 15

[4] IFAWA Local 3 Conference, December 19, 1947, box 11, folder 20, page 9; Kibre, “What to do About the Taft-Hartley Act,” December 19, 1947, box 11, folder 20; IFAWA Executive Board July 17-19, 1947, box 12, folder 4.

[5] IFAWA Local 3 Executive Board, February 8, 1947, box 12, folder 8.

[6] Report of the Secretary-Treasurer to the Local 3 Executive Board, August 23, 1947, box 7, folder 18.

[7] IFAWA Executive Board July 17-19, 1947. box 12, folder 4. Pages 7-8.

[8] Local 3 Executive Board February 28, 1948. box 12, folder 12

[9] Local 3 Conference, December 19, 1947, box 11, folder 20, pages 20-30; Local 3 Executive Board November 29, 1947. box 12, folder 8; 1940 Report by Paul Dale, United Fishermen’s Union Convention , box 1, folder 1; United Fishermen’s Union Executive Council May 5, 1945. box 5, folder 3; Ibid., January 9, 1943. box 5, folder 1.

[10] Ninth IFAWA Convention, January 20-23, 1948. box 11, folder 24, page 2

[11] Local 3 Executive Board, July 1, 1947, box 12, folder 8; IFAWA Executive Board, July 17-19, 1947. box 12, folder 4, page 7

[12] Local 3 1947 Conference December 19, 1947, box 11, folder 20, page 27.

[13] Department of Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United States 1951 (82nd Congress, Serial Set No. Serial Set No. 11544), 665.

[14] There were 12,242 fishermen and 15,948 shoreworkers in Alaska in 1947. See: Fisheries of Alaska: Annual Summaries 1942-1966 (Washington, D.C. : U.S. Deptarment of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service). In previous years, there were more fishermen than shoreworkers in Washington, Oregon and California, leaving the totals for each group roughly equal. See: Fielding, Fishery Industries of the United States 1939, 475-491; 542.

[15] Gerald Mayer, “Union Membership Trends in the United States,” (Congressional Research Service, 2004). The Department of the Interior sometimes designated Washington, Oregon and California as the ‘Pacific Coast’ and separated Alaska, but I use the term to describe all four areas.

[16] Ninth IFAWA Convention , box 11, folder 24, page 20. It does not appear that affiliation ever took place.

[17] “San Pedro Local 33 Wins Over Taft-Hartley” IFAW, February 1948, 16.

[18] Northwest IFAWA Council, February 14, 1948, box 11, folder 17; Ibid., Constitution, box 11, folder 15.

[19] Northwest IFAWA Council, December 18, 1948 Seattle, box 7, folder 1

[20] Local 3 Conference, December 17, 1948., box 7, folder 1.

[21] Memorandum on Claims made against IFAW by those advocating disaffiliation of AFU, box 11, unfoldered.

[22] “Plan Gillnetting Organizing,” IFAW, December 1948, 3; Northwest IFAWA Council, December 18, 1948, box 7, folder 1. Page 7.

[23] Ninth Convention IFAWA January 20-23, 1948.box 11, folder 24. Page 6 ;13; Resolution # 36, “District Organization” at Ninth Convention. Not contained in records, see: NW IFAWA Council February 14, 1948. box 11, folder 17. Page 2.

[24] “Anchorage Conference Welds Unity,” IFAW, March 1948, 1; IFAWA Executive Board August 26, 1948. box 12, folder 6, page 2.

[25] “Anti-Picketing Law Upheld at Redding,” Seattle Times, February 28, 1939, 14; UFU E-Conference February 11, 1945. box 5, folder 3; Hearing Subcmte Ed and Labor - Communist Infiltration of Maritime and Fisheries Unions, page 34.

[26] IFAW, August 1949, 7; IFAW, March 1948, 8.

[27] IFAWA Executive Board, August 26, 1948, box 12, folder 6, pages 9; 3.

[28] Local 3 Executive Board August 28, 1948, box 12, folder 12; IFAWA Executive Board July 17-19, 1947, box 12, folder 4, page 3; “Bellingham for Wallace,” IFAW, October 1948, 4

[29] Ninth Convention IFAWA, January 20-23, 1948, box 11, folder 24, page 57.

[30] Local 3 Executive Board, January 31, 1948, box 12, folder 8, page 4

[31] “King Resigns in San Pedro” IFAW, August 1948, 4.

[32] Ibid., page 7

[33] Local 3 Conference, December 17, 1948, box 7, folder 1, page 5; Preliminary Report on CIO Trial of IFAWA, submitted by Paul Pinsky. box 11, unfoldered; IFAWA Convention, Labor Union Constitutions and Proceedings, 22-2.

[34] House Committee Education and Labor, “Communist Infiltration of Maritime and Fisheries Unions,” Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office,1948), 52.

[35] “New Ruling Upholds IFAWA Stand on Our Collective Bargaining Rights,” IFAW, July 1948, 9.

[36] IFAWA Executive Board August 26, 1948, box 12, folder 6; Local 3 Executive Board August 28, 1948, box 12, folder 12

[37] Ibid.

[38] IFAWA Convention, Labor Union Constitutions and Proceedings, 3

[39] Ibid., Page 67; IFAWA Executive Board January 23-25, 1949, box 12, folder 6; Report on Alaska Herring Industry and Puget Sound Canned Salmon Industry, National Labor Bureau,April 29, 1949, box 11, folder 2.

[40] IFAWA Convention, Labor Union Constitutions and Proceedings, 61.

[41] Local 3 Executive Board February 19, 1949, box 12, folder 10, page 13

[42] IFAWA Convention, Labor Union Constitutions and Proceedings, 65-79; Background of Discussions on Merger, To All Locals and Delegates from International Officers, February 2, 1949, box 7, folder 1; Gettings to Editor, IFAW, February 9, 1949, box 7, folder 2

[43] IFAWA Executive Board January 23- 25, 1949, box 12, folder 6, pages 3-4; Local 3 Executive Board, February 19, 1949. box 12, folder 10, pages 14-24; Eleventh IFAWA Convention, 1950, box 12, folder 13, pages 4-5.

[44] IFAWA Executive Board January 23-25, 1949, box 12, folder 6, page 5.

[45] “Convention Adopts Fish Price and Wage Program for 1949,” IFAW, February 1949, 7.

[46] Juneau Conference of IFAWA and FTA Representatives, March 18, 1949, box 11, folder 18; “Alaska Cannery Workers Forge Unity for Action,” IFAW, April 1949, 6.

[47] “News From Nashoalook” IFAW, June 1949, 12; IFAWA Executive Board October 10-11, 1949, Seattle. box 12, folder 6

[48] “AFU Accepts Bristol Bay Agreement in Close Vote,” IFAW, June 1949, 7.

[49] Herring Fishermen Materials, box 10, folder 17; “Herring May Operate” and “Not So Happy,” International Fishermen and Allied Worker, July 1949, 3; 11; IFAWA Local 3 Executive Board January 7, 1950, box 12, folder 10

[50] “IFAWA Wins Gains for Season on Puget Sound,” IFAW, August 1949, 3; “Salmon Price Offer Rejected,” Seattle Times, July 8, 1949, 12; “Puget Sound Purse Seiners Remain Ashore,” Seattle Times, July 19, 1949, 4; “Canneries Offer Wage Increase,” Seattle Times, July 24, 1949, 10; “Fish Workers Accept Contract,” Seattle Times, July 26, 1949, 7; July 25, 1949 Special Salmon Meeting, Tacoma, box 7, folder 24; Telegrams, July 18, box 10, folder 18.

[51] “Fishermen’s Strike Spreads in Alaska,” Seattle Times, July 1, 1949, 4

“Fishermen Reject Packer’s Offer,” Seattle Times, July 3, 1949, 14; “Columbia River Fishermen Win 17 ½ For Chinooks” IFAW, August 1949, 11.

[52] JN Planich, Fishermen’s Packing Corporation to IFAWA Local 3, September 30, 1949, box 11, folder 16

[53] Recommendation from the Negotiating Committee to the Special Meeting of October 3rd , box 11, folder 16

Local 3 Emergency Meeting, October 3, 1949, box 11, folder 16; Robert Cummings to all Members, October 4, 1949, box 11, folder 16;Recommendations of Strike Committee Local 3. box 11, folder 16.

[54] Secretary Treasurer Report to Executive Board and Strike Committee , October 17, 1949, box 11, folder 16.

[55] Ninth Convention IFAWA, January 20-23, 1948, box 11, folder 24.

[56] Citizens of Anacortes, Pamphlet, box 11, folder 16; “Sound Salmon Fishermen Will Strike Tomorrow” Seattle Times, October 4, 1949, 1.

[57] To all Crew Members, November 2, 1949. box 11, folder 16; Policy Committee, October 5, 1949, box 11, folder 16; To All Members October 4, 1949, Robert Cummings. box 11, folder 16

[58] US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census, “Current Population Reports: Consumer Income,” (1951), <http://www2.census.gov/prod2/popscan/p60-007.pdf>.

[59] Robert Cummings to Ben Brockman, October 11, 1949, box 11, folder 16

[60] Jurich telegram, box 10, folder 18; “Seiners to Be Freed If Canners Agree on Prices,” Seattle Times, October 19, 1949, 9.

[61] “Purse Seiners Reject New Offer,” Seattle Times, October 12, 1949, 8.

[62] Transcript, Reports from Labor, October 17, 1949, box 11, folder 16

[63] Reports From Labor, October 17th, 1949, Jerry Tyler Papers.

[64] JN Plancich to Local 3, October 20, 1949, box 11, folder 16; Secretary Treasurer Report Executive Board and Strike Committee, box 11, folder 16, page 3.

[65] Ibid., 2-3

[66] Reports from Labor, October 17, 1949, box 11, folder 16, page 3.

[67] Agreements, box 10, folder 40.

[68] Report to the Membership, October 25, 1949, box 11, folder 16.

[69] “Fresh Fish Pact Reached, “ Seattle Times, October 27, 1949, 2.

[70] George Hecker, Booth Fisheries Corp to Seine Boat Frisco and Owners, October 29, 1949, box 10, folder 40

San Juan Fishing & Packing Co. to Boat Captains, October 21st, 1949, box 11, folder 16.

[71] Local 3 Executive Board January 7, 1950, box 12, folder 10; United Fishermen’s Union Conference, December. 20- 21, 1945, box 4, folder 37.

[72] Statement of Delegates of IFAWA at National CIO Convention. box 12, folder 6. Page 3; Local 3 Conference December 15-17, 1949 Seattle. box 12, folder 10

[73] IFAWA Local 3 Executive Board January 7, 1950. box 12, folder 10

[74] “‘We Have Only Begun to Fight the Anti-Trust Case,’” IFAW, October 1949, 1.

[75] Eleventh IFAWA Convention, 1950, January 28, Afternoon Session, box 11, unfoldered.

[76] Ibid., page 4.

[77] Ibid., January 27th Afternoon Session, Discussion of Resolution #28.

[78] Ibid., pages 4-6.

[79] Ibid., 6-8

[80] IFAWA Executive Board April 4-5, 1950, box 12, folder 13; Policy Statement on Alaska by IFAWA Executive Board., In: IFAWA Executive Board April 4-5, 1950. box 12, folder 13.

[81] Jurich to Affiliates, May 2, 1950, Local 3, May 25th, box 12, folder 13.

[82] Preliminary Report on CIO Trial of IFAWA, Paul Pinsky, box 12, folder 13.

[83] “Far North Unionists Plan 1950 Wage Boost Campaign,” IFAW, December 1949, 9.

[84] “IFAWA Convention Takes Bearing on Fishing Industry,” IFAW, January 1950, 1; Reports from Labor, May 18, 1950, Jerry Tyler Papers; IFAWA Executive Board, April 4-5, 1950, box 12, folder 13, page 10; Special Broadcast June 8, Jerry Tyler Papers, “June 5-8, 1950, AFAWA” folder.

[85] “Hosie Calls Meeting on Salmon Strike,” Seattle Times, May 31, 1950, 8.

[86] Reports from Labor, May 11th, Jerry Tyler Papers,https://depts.washington.edu/dock/Mangaoang_Ernesto.shtml “Picket ASI in Wash.,” IFAW, May 1950, 7.; Reports from Labor, May 25, Jerry Tyler Papers.

[87] IFAWA Executive Board, May 25, 1950, box 12, folder 13. Page 4

[88] Reports from Labor, May 11th, Jerry Tyler Papers; “Labor Troubles Bring Eskimo to Seattle,” Seattle Times, May 11, 1950, 14; “Union Demands Eskimo Leader Return North,” Seattle Times, May 18, 1950, 57.

[89] “ILWU Local Union 7C Places Pickets at Cannery Installations as NLRB Seeks Two Injunctions,” Alaska Weekly, May 29, 1950 page 1.

[90] Reports From Labor , May 25, 1950, Jerry Tyler Papers;, May 30, 1950; “Alaska Salmon Seiners Win $100 Gain Per Man,” IFAW, June 1950, 20.

“Salmon Picket Injunction Opens,” Seattle Times, May 27, 1950, 2. Note: It is unclear what day ASI employees in Local 3 went on strike.

[91] Reports from Labor May 25, 1950, Jerry Tyler Papers.

[92] “Hosie Calls Meeting on Salmon Strike,” Seattle Times, May 31, 1950, 8.

[93] Reports From Labor , May 30, 1950, Jerry Tyler Papers.

[94] IFAWA Executive Board, May 25, 1950, box 12, folder 13; Reports from Labor, June 6, 1950, Jerry Tyler Papers

[95] “Two Unions Support ILWU in Fish Tieup,” Seattle Times, May 25, 1950, 8.

[96] Deposition of Robert Cummings, in Pacific American Fisheries Inc vs. IFAWA, box 14, folder 1;District Court US, Western Division of Washington, Northern Division, June 8, 1950, box 14, folder 1.

[97] “Victory Meeting,” IFAW, July 1950, page 15; “Alaska Salmon Seiners Win $100 Gain Per Man,” IFAW, June 1950, 20.

[98] Reports from Labor, June 6, 1950, Jerry Tyler Papers

[99] Ibid.; “Waterfront Solidarity Wins Smashing Gains For Alaska,” IFAW, June 1950, 3.

[100] “Union Charter May Rekindle Alaska Labor Troubles,” Seattle Times, June 7, 1950, 12; “Bristol Bay Union Dispute Goes to Court,” Seattle Times, July 14, 1950; “Bristol Bay Cannery Work Faces Delay,” Alaska Weekly, June 29, 1951, 1.

[101] “Long Salmon-Cannery Strike in Bristol Bay Area Settled,” Alaska Weekly, July 8, 1951, 1.

[102] Hébert, “Wild Dreams,” 202; “Bristol Bay Priest Predicts Defeat for ‘Reds’ In Area,” Alaska Weekly, May 23, 1952, 5; “Fish Packers File Charges Bristol Bay Charges,” Alaska Weekly, June 8, 1951, 1.

[103] “Long Salmon-Cannery Strike in Bristol Bay Area Settled,” Alaska Weekly, July 8, 1951, page 1; Showing successorship of BSFU-AFL to Local 46: “Trust Fund Goes to Work,” The Beacon of Dillingham, January 29, 1952, 1.

[104] “Union Cauldron Comes to Boil,” The Beacon of Dillingham, February 27, 1952, 2; For a first-hand but very factually flawed account, see: Jonathan Hughes, “The Great Strike at Nushagak Station, 1951: Institutional Gridlock,” The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 42, No. 1 (1982); See also: Hébert, “Wild Dreams,” 203.

[105] Ivan Ascott, “The Alaska Statehood Act Does Not Guarantee Alaska Ninety Percent of the Revenue from Mineral Leases on Federal Lands in Alaska,” Seattle University Law Review 27 (2004): 1008-1010.

[106] Alexander Morrow, “Hawaii,” In Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-class History¸ Eric Arnesen, Ed., 573-5; George Cooper and Gavan Daws, Land and Power in Hawaii (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990).

Alaska is different from Hawaii in that Governor Gruening and non-voting US Congressional representative Dimond were liberal Democrats. However, their power was repeatedly sidelined by the ASI and other big economic interests, and federal officials. See, for e.g.: Ergenst Gruening, “Let Us Now End American Colonialism,” <http://www.alaska.edu/creatingalaska/-convention/speeches-to-the-conventio/opening-session-speeches/gruening/>

[107] “Anti-Trust Indictment In San Pedro Aids Canneries” IFAW, July 1950, 3.

[108] “Anti-Trust Trial Set,” IFAW, October 1950, page 7.

[109] “ ‘New Deal’ Offers Benefits To Small Boat Fishermen,” IFAW, September 1950, 19.

[110] “Union Exposes Real Price-Fixers in Fish Industry,” IFAW, November 1950, 1; “Caucus to Mobilize ILWU Strength in Fishing Industry,” IFAW, December 1950, 1.

[111] Local 3-3 Conference, January 3-4, 1951, box 13, folder 31.

[112] Local 3 Executive Board, September 15, 1951, box 13, folder 31.

[113] Fishermen and Allied Workers Division Executive Board, August 11, 1951, box 13, folder 31.

[114] “Company Unionism Wins in Columbia River Poll.” IFAW, February 1951.

[115] “Alaska Fishermen’s Union Receives ILWU Charter,” IFAW, October 1950, 9.

[116] Local 3 Executive Board, December 1, 1951, box 13, folder 31, page 3

[117]“San Francisco Dragboat Men Winning Fight For ‘New Deal,’” IFAW, January 1951, 5; “Militant Dragboat Men Win Strike in San Francisco,” IFAW, February 1951, pages 1; 12.

[118] “SF Dragboat Men Fight Determined Campaign to Consolidate Victory.” IFAW, March 1951, 9.

[119] Local 3, April 14, 1951, box 13, folder 31, pages 5-6.

[120] Jeff Kibre to Norman Leonard, George Anderson and Jurich, June 25, 1965, box 13, folder 19; Francis Gannon, Biographical Dictionary of the Left Vol 3 (Boston: Western Islands, 1969), 60.

[121] ILWU Executive Board October 10-11, 1950. Seattle. box 12, folder 13

[122] “CRFPU Fights to Save Union From Canners’ Disruption,” IFAW, July 1950, 10.

[123] “CRFPU Votes 3-1 For ILWU” IFAW, August 1950, 9.

[124] “CRPU Goes Independent” Clatskanie Chief, January 11, 1952.

[125] Puget Sound Contract Committee and Executive Board, April 8, 1952, box 13, folder 41; J. Steele Culberston, ASI, to Local 3-3, May 28, 1952, box 14, folder 1.

[126] Puget Sound Negotiating Committee for Fall Season 1953, box 15, folder 48.

[127] Robert W. Graham, Bogle Bogle & Gates, to NEFCO, March 26, 1954, box 14, folder 24.

[128] Local 3 Executive Board, October 1, 1955, box 17, folder 15.

[129] JD Cooper, Alaska Packers Association, to Jurich, July 19, 1957, box 14, folder 2; SG Tarrant, Pac Am Fisheries, to Jurich July 26, 1957, box 14, folder 2; Tendermen’s Agreement, June 20, 1957, box 14, folder 3

[130] Purse Line, August 1957. box 16, folder 25; June 1958.

[131] Ibid., September 1958; May 1959

[132] “Organization of Divided Fishers,” in Uncommon Property Marchak, Guppy McMullan. Eds., 230-1; 27.

North and Griffin, A Ripple, A Wave, 36-40. ; Benjamin Isitt, Militant Minority: British Columbia Workers and the Rise of a New Left, 1948-1972 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press,2011), 150

[133] Ibid., 160-1; Charles Menzies, “Us and Them: The Prince Rupert Fishermen's Co-op and Organized Labour, 1931-1989,” Labour 48 (2001); Stephen Hume, “‘He was the Best of Who We Are’: Tribute to Gritty Labour Leader Homer Stevens,” Vancouver Sun, October 19, 2002.

[134] CAW-TCA, “Fisheries,” http://www.caw.ca/en/sectors-fisheries.htm; “A Profile of the Membership,” <http://www.caw.ca/assets/pdf/08-Chapter_3.pdf>

[135] Local 3 Executive Board, September 30, 1961, box 13, folder 3.

[136] NLRB Form 1080, Certificate of Union Officers, box 13, folder 11; Copy of December 1, 1956, box 13, folder 2.

[137] Radke , Pacific American Fisheries, 168-70.

[138] NLRB, Representation Election at Fishermen’s Packing Corp, July 1, 1976. box 13, folder 13.

[139] “Joseph F. Jurich, First President of Fishermen’s Union, Dies at 83,” Seattle Times, September 29, 1984, D20.

[140] Ken Lane, To Whom It May Concern, September 18, 1980, box 13, folder 19.

[141] Puget Sound Fish Cannery Workers Agreement, January 1, 1980, box 15, folder 6.

[142] ILWU Executive Board January 22, 1982. box 13, folder 20

[143] Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations, www.pcffa.org/; LA Times, “Dungeness Crab Season Starts After Fishermen sStrike $2.25-A-Pound Deal,” November 29, 2011, http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/money_co/2011/11/dungeness-crab-season-starts-after-fishermen-strike-225-a-pound-deal.html; Corey Pein, “Fisherman’s Wrath: A Campaign Targeting Gillnetters Takes Class War to the Columbia River,” Willamette Week, June 13, 2012. <http://www.wweek.com/portland/article-19314-fisherman%E2%80%99s_wrath.html>

[144] Dorothy Sue Cobble and Leah Vosko, “Historical Perspectives On Representing Non-Standard Workers,” in: Nonstandard Work: The Nature and Challenges of Changing Employment Arrangements, ed. Carre, Feber, Golden and Herzenberg (Champaign, IL: Industrial Relations Research Association, 2000).