Fishermen seining salmon, probably British Columbia (Photo UW Libraries Digital Collections)

This essay is presented in five chapters.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Early Unionism in the Pacific Coast Fisheries

Chapter 3: A Coastwise, Industrial Union

Chapter 4: World War II

Chapter 5: Struggle, Strikes and Collapse

Leo Baunach's essay won the 2013 Library Research Award given by University of Washington Libraries.

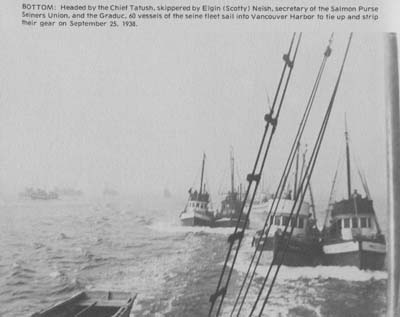

Sixty vessels of the seine fleet head into Vancouver harbor to tie up in 1938 strike

by Leo Baunach

The International Fishermen and Allied Workers of America burst into existence in early 1939, following a gestation that had lasted two years and depended upon a complicated set of earlier mergers, jurisdictional adjustments, and organizational name changes. The industrial union combined cannery and fishery workers up and down the West Coast and crossed the craft boundaries that had long seen fishermen organize according to the type of gear or catch. The process had begun with the Federated Fisherman’s Council of the Pacific, forged within the collapsing International Seaman’s Union of the Pacific in the last days of 1936. That loose confederation of still independent regional unions was led by radicals who were determined to bring these organizations into the newly forming CIO and equally determined to create a genuine industrial union that united all workers in the far flung western fishing industry.

The merging of purse sein unions up and down the coast into the United Fisherman’s Union (UFU) in 1938 marked a second step. Although still technically a craft union, the UFU began to reach out beyond purse seiners. The latter included the Fish Reduction Workers, Salters and Gibber’s Union that joined the UFU-Puget Sound alongside a growing number of cannery locals in places like Anacortes. The Puget Sound District incorporated other new groups, including a local of reefnetters from Lummi Island. This represented concrete process in building an organization that knit together geographically disparate fishermen, different gears, and shoreworkers [1]

With the pro-CIO affiliates of the Federated Fishermen's Council united in the UFU, leaders redoubled their efforts to bring the entire Federation into the CIO as an International. While working to build a full federation independent of the AFL, the CIO had proposed that the Federated Fishermen's Council be given a charter as a full International union. The CIO was particularly interested in the idea because of its strength in other waterfront sectors. Within the Fishermen's Council, firm decisions were repeatedly stalled. When the Alaska Fishermen's Union, the largest and oldest of the fishing unions in the Seamen's Union, joined the United Fishermen in supporting a CIO charter, the two groups pushed ahead and held a vote at the opening of the December 1938 Convention of the Council to accept the CIO charter and make the gathering the founding Convention of the International Fishermen and Allied Workers of America. It was a gamble, as the the Pacific Coast Fishermen's Union opposed the move. Delegates from groups like the Columbia River Fishermen's Protective Union voted for proposal to accept a CIO charter, but their organizations were still undecided on the question of joining the new organization. The risky strategy paid off, and all members of the Federated Fishermen's Council ultimately joined the new International by mid-1939.

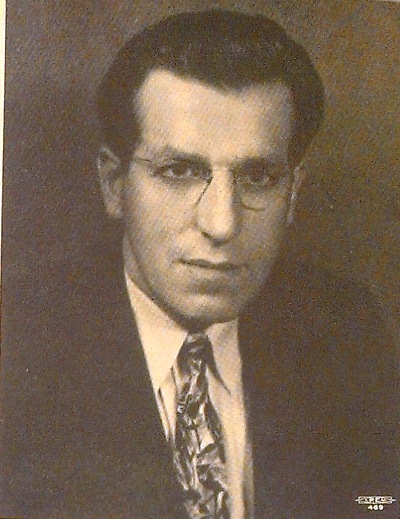

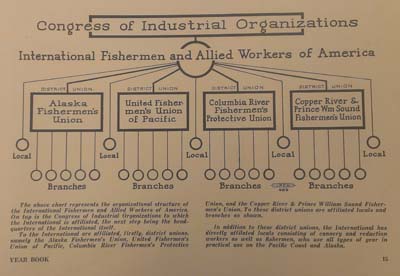

After approving the CIO charter, the Federated Fishermen’s Council went straight to work approving a Constitution for IFAWA and designated Seattle as the new body’s headquarters. 300 copies of the convention minutes were printed to ensure that all locals and members had access to the discussion.[6] Fifteen nominations were made for President, but only Matt Batinovich and Joe Jurich, both from the United Fishermen’s Union, accepted. Jurich carried the vote. George Hecker and Martin Olsen, both of the Alaska Fishermen’s Union, became the Vice-President and Secretary-Treasurer respectively. As the Convention ended, the birth of IFAWA still hung in the balance while the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union and the Copper River and Prince William Sound Fishermen’s Union pledged to hold votes on affiliation. Both decided in favor of the idea, and the PCFU later reversed course. With that, the first Executive Board meeting of IFAWA was held on May 2, 1939.[7]

Joe Jurich, IFAWA's first president, elected at founding convention, May 1939

The unions that united to create IFAWA decided not to fully merge their internal structures, and Canadian affiliates did not join the new union. Both were barriers to institutionalization that would have serious consequences in the late 1940s..

The autonomous British Columbia branches of the Salmon Purse Seiners and the Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union expressed interest in potentially joining the new International, but a separate process of fishery union consolidation in BC quietly prevented it. Instead, BC fishermen coalesced into an industrial union in 1945 under the name United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union (UFAWU). [8] The BC unions maintained warm relations with their US counterparts, sending fraternal delegates to every convention until the late 1940s, when US Border Patrol denied entry to individuals associated with the Communist Party.[9] In 1938, the BC Salmon Purse Seiners Union conducted one of the most dramatic fishing strikes on record. They waited until the salmon fleet was together on the water to call the strike, ensuring that no union boat could sneak out of harbor and scab. Demanding minimum prices and a union recognition from the association of salmon packers, they sailed in formation toward Vancouver to return the nets they rented from the packers – but not before sabotaging the gear by cutting it up. They continued to tour ports around BC, stopping to negotiate with the companies and visiting a lumber worker strike, before returning to Vancouver to block scab boats from offloading their catch.[10] The dramatic ‘sail-in’ strategy was never to be repeated.-

The limits of working-class solidarity

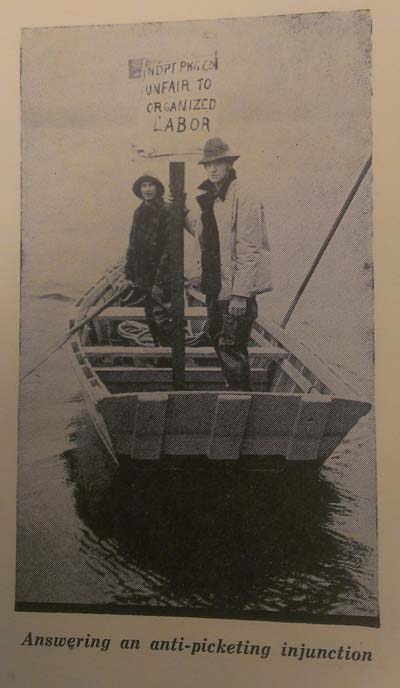

Picket Boat, location unknown, 1940 Convention Yearbook

The effective use of the strike by these fishermen, and the working-class solidarity with lumber workers illustrates a strong belief among fishermen that they were workers. In the historically and geographically specific period examined in this essay, the working-class status of fishermen was self-evident and compatible with strong notions of independence and self-reliance.[11] Failures in fishery worker unionization are often attributed to these attitudes, because they contrast with the collective solidarity inherent to unionism. In reality, work aboard fishing boats required precise coordination, and constant reliance on other members of the crew. This cooperation on-board was an extension of the social networks of ethnic fishing communities, and the two built upon each other. Fierce independence was less about individualism than the ability to self-determine working patterns, methods and where to fish. Further, this independent streak nurtured an oppositional attitude toward the packers. Collective association emerged as the best strategy to prevent attempts by packers to regulate and discipline their labor.[12]

Whether formalized or not, ethnic separation and discrimination was a far worse barrier to organization than the misclassification of fishermen by packers. At times, union locals operated in practice as ethnic associations that engaged in collective bargaining. In these cases prejudice precluded organizing, or made those outside of the CIO fishermen’s base among Yugoslavian and Scandinavian immigrants wary of joining an organization led by another group.[13] This had grave consequences in San Pedro, where Yugoslavians were the majority. In the rest of Southern California, Italians were the dominant group. The packers split the Japanese and Italians from the United Fishermen’s Union in the port of San Pedro, convincing the two groups to fish during 1939 lockout that temporarily busted the local.[14] The Italians later formed the basis for a breakaway AFL local.[15] Compelled by an anti-discrimination policy of the International Seamen’s Union to organize a Japanese auxiliary to the union in Monterey, Matt Batinovich once expressed with some surprise that “many of the Japanese proved to be just as good [unionists] as any other race.”[16]

This kind of prejudice damaged broad-based organizing, but ethnicity was a double-edged sword. San Pedro was a stronghold of the communist Fishermen and Cannery Workers Industrial Union and later IFAWA, in part because of ethnic and familial networks that became a conduit for organizing. A case in point is the Zuanich family, based out of Bellingham and an important part of the Puget Sound fishing community. Phil Zuanich immigrated to the US from Croatia and began fishing on the Columbia River in 1907, becoming an active member of the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union. He later moved to Bellingham and was active in the early days of the Salmon Purse Seiners Union alongside Pete Zuanich, who later served a 43 year term as the city’s port commissioner. Many members of the clan lived in San Pedro and maintained close communication and ties with Puget Sound. Vince Zuanich, and probably others, worked aboard vessels in both areas.[17] Networks like this one were probably an important aspect in the creation and maintenance of a coastwise union. The family remained involved with and tied to the union throughout IFAWA’s history. Nick Maratinich, former President of IFAWA Local 33 in San Pedro, moved to Bellingham in 1946 after marrying a member of the Zuanich family. Maratinich’s sister also married a member of the family in San Pedro, and the two were active in the union. When Maratinich arrived in Bellingham, one of his first outings was to accompany Phil Zuanich and Louise Otten, a writer for the union newspaper, in soliciting advertisements from local businesses.[18]

Cooperatives proved to be an even more problematic than ethnic exclusivity for IFAWA and its affiliates. The cooperative approach conceived of fishermen as independent entrepreneurs who could band together to sell their product, in direct opposition to the idea of fishermen as misclassified and marginalized workers. Often, the cooperatives took the form of ‘marketing associations’ that pooled resources to improve their gear and obtain favorable deals with the packers. In the latter aspect, cooperatives were similar to unions in that they leveraged collective association to improve income, but the relationship of cooperatives and packers was thought of as one business to another. This made cooperatives averse to confrontation and wary of closed shop agreements. At a tense meeting with fishing union representatives in 1938, the Fishermen’s Cooperative Association argued that it was better to join a cooperative than strike, because the cooperative had the resources to freeze and store fish during an impasse in negotiations. The Cooperative filed for an injunction against the Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union after it demanded Cooperative members join as individual members if they wanted to fish for closed shop canneries. Earlier, the Cooperative had been open to becoming a PCFU affiliate, but the meeting devolved into accusations that the union blacklisted cooperative members. Union representatives fired back that “Cooperatives should realize they are not organizations entirely separate but are part of the working class movement.”[19] As a result of divisions like this one, cooperative members often scabbed on strikes or otherwise undermined the negotiation of prices.[20] The early formation of a cooperative cannery on the Columbia River is an important but unique example of a cooperative based on working class consciousness. In San Pedro during the late 1930s, the United Fishermen’s Union attempted to form a union-backed cooperative, but the packers conspired to destroy it by raising prices paid to non-union fishermen and artificially depressing local consumer prices, squeezing the nascent cooperative into insolvency.[21]

The existence of anti-union cooperatives shows that a section of West Coast fishermen identified as petty capitalists, but IFAWA’s sizes suggests that the vast majority thought of themselves as workers. Faced with frequent price and weight gouging, arbitrary prices, and permanent debt there was little mystery clouding true nature of fishermen and packers.[22] For union organizers, the task was less about overcoming the myths of self-sufficient and entrepreneurial fishermen – which most workers easily recognized as false given the concentrated economic power of the packers – and more about convincing them that the benefits of unionization outweighed its risks. In doing so, IFAWA and its forerunners gave structure to the spontaneous impulses among fishermen to take collective action and provided them with a sustainable way to build power and change the conditions of the overall industry.

Successful coastwise organization meant recalibrating union organizing to account for the rampant misclassification of fishermen. One of the biggest breakthroughs made by IFAWA was to abandon the practice of denying membership to owner-operators, men who owned the boats they fished on and hired a crew to help out. A simplistic vision of class struggle and control of the means of production led the Fishermen and Cannery Workers Industrial Union to deny owner-captains membership, but IFAWA identified the crux of labor-capital relations as the exchange between fishermen and packers.[23] However, the admission of owner-operators, often deeply indebted to the packers, was a hotly debated topic throughout the history of IFAWA. The union was careful to provide for methods by which owner-operators could be expelled and strictly prohibited membership to owners who did not work aboard their vessels.[24] In many areas and gears like purse seining, an association of vessel owners negotiated contracts with the union covering working conditions.

Creative organizing and membership engagement tactics that accommodated the idiosyncrasies of the fishing industry were essential to the formation and growth of the International Fishermen and Allied Workers.[25] The structure and geography of fishing work presented a myriad of challenges. First, fishermen were seasonal, and sometimes lived and found off-season work in a different city from the port where they gained employment, which could also be in a different place from where they fished. Second, some catches required long periods at sea while others allowed the boat and its workers to return to port daily, weekly or on a semi-regular basis. The most important union tactic formed to fit the industry was boat clearing. A boat and its crew had to be approved by a union representative to leave port, or face sanctions. This made closed shop agreements particularly important because if a cannery signed such an agreement, the union could bar boats that failed to clear from selling to the facility. In many cases, representatives gave cleared boats union flags or signs to easily indicate to canneries, tenders and other boats that it was union approved.[26] To be cleared, all crew had to be union members who were up to date on their dues, and a shop steward called a boat delegate was selected. Boat delegates were a particularly important part of this system. Union representatives and staff covered larger areas, meaning they were usually not immediately available, and most boats spent days or weeks away from land. Even more than in other industries, stewards were the first line of defense to ensure that the contract was followed. Grievances were dependent upon their ability to carefully compile evidence so a complaint could be filed upon the return to port.[27] Clearing provided organizers with time to talk face-to-face with members, a rare opportunity to build union identification among members that did not or could not attend meetings. It was also the backbone of the union’s card signing and new member outreach, providing fishermen who had never worked under a union contract with an in-person introduction. Dues collection was entirely hand-to-hand because payroll deductions were not possible, and clearing was a crucial time to keep members in good standing. In addition to providing predictability in prices, IFAWA made itself relevant and visible to the rank and file by ending widespread weight gouging by packers. The exact method varied by contract and cannery, but agreements always required some form of verification of catch weight by someone outside of management. In some cases, a union representative or worker selected by his coworkers did the weighing, or management and a union member jointly oversaw the process.[28]

Salmon Coordinating Committee, 1942 Newsletter

In addition to being the cornerstone of the union, boat delegates were the main method by which ballots and information were distributed to members.[29] These items, including union newsletters, bulletins and updates were important in making up for the geographic and seasonal limitations on union meetings. IFAWA first relied on the Voice of the Federation, a publication of the CIO’s Maritime Federation of the Pacific, and The Fisherman, jointly published by the Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union and the Salmon Purse Seiner’s Union, in addition to smaller newsletters and written updates.[30] The Voice and Fisherman ceased production around 1940, and IFAWA began publishing its own news bulletin, IFAWA Views the News. In 1943, it upgraded to a monthly, tabloid-style newspaper with extensive original content. The International Fisherman and Allied Worker grew to a high quality, illustrated product with over twenty pages of original content by dedicated staff and volunteer writers. It not only provided union news and updates, but practical information about fishing runs, seasons, employment, technological changes, conservation, and government policy. Additionally, the paper carried social items and entertaining accounts of events in the lives of IFAWA members. This fluid combination, which avoided a didactic focus on unionism and politics, helped build an imagined community of fishermen despite their separation. This kind of mutuality was, in turn, a building block of a stronger union.

No matter the skills and effective tactics of an organizer, their fellow workers need to be receptive. The milieu of waterfront militancy, the predominance of Eastern and Northern European immigrants with links to radical and labor traditions, and the experiences of fishermen in off-season industries laid the groundwork for unionization. The West Coast waterfront was one of the most important sites of left-led, democratic unionism, birthing unions like the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) and the Marine Cooks and Stewards. As shown in San Pedro fishermen for the 1934 longshore strike, fishermen were an essential – if often unrecognized – participant in the emergence of radical unionism in the ports of the West Coast. In addition to off-season longshoring, fishermen gravitated toward the lumber industry and trucking, where they did not have to commit to year-round employment. They likely carried over the ideas instilled in them by struggles in these other industries, including trucker fights against misclassification. Finally, the fishing industry was dominated by Scandinavians, Slavs and other immigrants from the peripheries of Europe. Many of these communities had radical traditions, like the Finnish community in Astoria that was a stronghold of the Socialist Party.[31] The International Workers Order (IWO), a Communist Party-backed network of ethnic fraternal organizations, made significant progress among Eastern and Southern Europeans. There were also significant numbers of Communist Party members and radicals in more mainstream organizations like the Croatian Fraternal Union.[32] In immigrant communities like South Bellingham, the entire community was tied to the industry, making community politics an essential and valuable base for worksite action.

Anton Susanj showcases some of these elements. He immigrated to Washington State from Croatia in 1913 and found work in logging, mining and smeltering. In the coal industry, he participated in unionization struggles in Cle Elum. In Bellingham he was a member of the Croatian Fraternal Union and is fondly remembered for his promotion of Croatian music and culture. In 1927, he began to work in the fishing industry and later became a charter member of the United Fishermen’s Union. He went on to serve as Business Agent, Executive Council member and Secretary-Treasurer.[33] Susanj’s trajectory perfectly shows how union activism was not an activity that occurred in a vacuum or purely because of material conditions. Instead, it was part of a vibrant process of interaction and everyday life in the overlapping communities of laborers and immigrants. This process intertwined with the intervention of Communist Party organizers like Paul Dale, head of the United Fishermen’s Union in Puget Sound. He was born in Finland and immigrated at a young age to Astoria with his parents. He attended the University of Oregon, and perhaps influenced by the radical traditions of Astoria became a Communist Party member. In the early 1930s, he organized farmers on behalf of the Party before being transferred to Puget Sound to organize the Fishermen and Cannery Workers Industrial Union.[34]

Strong community roots and adroit organizing were needed as AFL raiding and the first round in attacks by packers and the US government threatened the new International Fishermen. A particular benefit of CIO membership was membership in the Maritime Federation of the Pacific (MFP), a longshore-led alliance of waterfront unions that fostered joint negotiations and cooperation. In particular, the Federation bolstered joint negotiations with the Alaska Salmon Industry (ASI), the business association of packers with operations in the Territory.[35] Joint negotiations with ASI had begun in 1935, but a new degree of unity was achieved after most unions representing ASI workers went CIO, including the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing and Allied Workers Local 7, which represented non-resident, seasonal Alaska cannery workers.[36] Because the headquarters of most ASI companies were in Puget Sound, non-resident fishermen and cannery workers could exert pressure before the season started. The Maritime Federation did so in 1939 by holding pickets at ASI-connected sites in Puget Sound during pre-season negotiations. The United Fishermen’s Union (UFU), now an affiliate of IFAWA, turned out in force for the pickets, but the packers succeeded in an effort to separate the UFU from the joint negotiation process. As a result, the UFU had to sign a contract with no gains after the joint negotiations concluded. Meanwhile, IFAWA efforts to expand in Alaska were stymied in 1939 because staff and officers were concentrated on setting up the office headquarters in Seattle.[37] On the Puget Sound, the Business Agent position remained vacant for a month when Paul Dale took over Jurich’s old post as head of the UFU Puget Sound district.

Organizational Chart of the International and Affiliates

The Business Agent was an important position as the AFL stepped up attempts to raid the union.. Nick Mladinich soon took over as Business Agent and made Anacortes his base of operations for the summer salmon season. Anacortes was the flashpoint of conflict between CIO and AFL fish cannery unions, a division that prevented both sides from gaining good contracts.[38] Mladinich successfully organized almost all workers on tender boats operating out of Anacortes– a key chokepoint in the fish supply chain.[39] In salmon, the UFU achieved a joint agreement for the fall season in the Sound and got closed shop agreements for canneries in La Conner, Blaine and Point Roberts, but lost four cannery worker elections by the end of the year.[40] Meanwhile, the Seafarers International Union-AFL (SIU) attempted to wrest control of tendermen in Puget Sound and Alaska, the latter being represented by another IFAWA affiliate, the Alaska Fishermen’s Union. The raid was unsuccessful but Seafarer interference prevented Bristol Bay fishermen from achieving a closed shop agreement.[41] The Seafarers Union also targeted California, gaining inroads in Monterey and San Pedro. In the latter, packers retaliated against a UFU strike by locking them out in summer 1938, greatly damaging the union and later providing SIU organizers with a foothold. The lockout had reverberations throughout Southern California as the United Fishermen’s Union launched an ill-fated strike demanding recognition. A fishermen’s affiliate of Seafarers gained the support of a majority of fishermen in Monterey. It was the first round in several years of bitter combat in the city between IFAWA and the AFL. [42]

The rise of a militant coastwise union greatly alarmed the packers. They turned to injunctions to stop collective bargaining, leveraging the misclassification of fishermen. The courts were generally receptive to the injunction requests despite the practical dynamics of an industry in which the packers set prices, and thereby the fishermen’s take-home pay, and asked that boats exclusively sell to one company. The first injunctions hit the Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union (PCFU), an IFAWA affiliate based in Oregon, which was on the verge of a closed shop agreement for the Northwest tuna fleet that operated out of Astoria. In 1939, Oregon packers filed an injunction against the union to prevent any price negotiations or a union clearing system. They argued that the PCFU did not constitute a labor union, and was therefore exempt from the Norris-La Guardia rules limiting injunctions and affirming the freedom of association. An initial federal court ruling concurred.[43] The case worked its way through the judicial system for several years until it was settled in 1942 in favor of the packers.[44] The tuna injunction was closely followed by a broader one filed by the Columbia River Packers Association that prevented price negotiations by the Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union. Moral was damaged, allegiance fell and dues payment plummeted. Legal fees and the need to concentrate the court case pulled resources away from organizing new or existing members, and the stress exacerbated internal division within the union. The injunctions legally prevented the Executive Board from making any decisions, and a new ‘General Organizing Committee’ was created using a loophole in the court order. The Committee demanded that IFAWA transfer the new Puget Sound Gillnetters Union into the PCFU, in a blatant play for dues money that proved counterproductive.[45] In 1940, a plan was formulated to reorganize the PCFU as several direct locals of IFAWA. The reasoning was twofold. First, the injunction only prevented the PCFU from operating as a union, but did not apply to any other organization of Oregon fishermen. Secondly, IFAWA was struggling to become more cohesive than the loose Federated Fishermen’s Council. The strong identity and organizational structures of the founding affiliates made this difficult. The head of the Oregon Fishermen’s Council, set up to carry out reorganization, wrote in 1940 that it was “no longer necessary to maintain an International within an International as under the International Seamen’s Union set-up.”[46]

Meanwhile, the situation for the United Fishermen’s Union in Southern California had deteriorated. The AFL had gained effective control of Monterey, San Pedro and San Diego. Membership in the California UFU District fell from 4,500-6,000 to less than 2,000 members by late 1940. It paralyzed the union’s ability to perform its basic functions like grievance and contract servicing and District leadership was uncommunicative about the problems.[47] The International pledged to financially support a rebuilding process, but the California UFU District proved unable to implement the plan. After this, IFAWA designed a new and more comprehensive plan to reorganize the area by pooling the financial and human resources of IFAWA, the California State Industrial Union Council and the ILWU.[48] The effort successfully reorganized 3,000 fishermen into ten IFAWA locals in 1941.[49]

An important actor in the reorganization of California was Jeff Kibre. He was a former leader in the dissident movement of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), an undemocratic and mob-run union of Hollywood studio workers. Kibre is an example of the importance of timely intervention by leftists to the success of IFAWA. In IATSE, he led a failed 1937 strike by rank and file members against the studios and corrupt union leadership. Kibre’s faction fought their opponents to a standstill and laid groundwork for the prosecution of the mob leadership, but he was blacklisted and agreed to a deal whereby he would leave the industry if IATSE promised to not attack his supporters.[50] By 1940, he was an IFAWA Business Agent in Southern California. He later became an at-large organizer and served as IFAWA Secretary-Treasurer for several years. His strong organizing skills and connections to the California labor-left community, including the ILWU, were crucial to the reorganization of Southern California fishermen. These connections were built through the Communist Party, which he had belonged to since agitating in the student movement at UCLA.[51]

To the north, the Alaska Fishermen’s Union (AFU) and the United Fishermen’s Union worked together to build IFAWA in the Territory. The AFU increasingly organized resident Alaskan fishermen on the basis of industrial unionism, but non-resident fishermen continued to dominate the union from its stateside branches.[52] IFAWA also worked with the Maritime Federation to hold an All-Alaska Labor Convention in early 1940. The Convention facilitated the creation of the United Trollers of Alaska, an amalgamation of existing IFAWA locals, members of the United Fishermen’s Union and small independent unions.[53] There were now 39 direct locals of IFAWA, and at least an equal number of locals housed within affiliates like the UFU.[54] Growth meant more financial resources and allowed the hiring of a full-time staffer for Northern Puget Sound gillnetters, among other expansions.[55]

New member organizing continued to be most successful in Washington, Oregon and California. Significant organizing took place in Alaska, but a planned organizing push to be led by Secretary-Treasurer George Lane was cancelled when he resigned in 1941. The resignation had a cascading effect in which President Jurich had to take over Lane’s duties, preempting him from travelling to the Gulf Coast to explore organizing there in conjunction with the expansion plans of the ILWU and National Maritime Union.[56] The fluid nature of membership and the inevitable challenges of hand-to-hand dues collection make it difficult to pin down the exact size of IFAWA.[57] Reflecting the fractured, federation-like nature of the International, affiliates like the United Fishermen’s Union continued to use separate membership and dues books. Until the post-war period, per capita membership – the total number of members upon which dues to the International had been fully paid – was between 9,000 and 12,000. This number was artificially low because of California United Fishermen’s Union and the Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union defaulted on payments during their troubles. The union estimated that real membership, meaning everyone covered by IFAWA contracts and paying some dues, was 20,000.[58]

With growth, there was significant movement toward price stabilization and better industry-wide working conditions. The UFU-Puget Sound signed 64 price and work agreements in 1941.[59] There was particular improvement in the working agreements with vessel owners. Clauses were added that ensured transparent accounting by boat owners to prevent crew wages from being diverted to pay for repairs, to establish clear work duties, and to ensure the provision of adequate medical supplies – a must given the dangerous nature of onboard work.[60] In many catches like salmon purse seining, a share system was standardized that divided profit between the vessel owner, crew and costs. For example, in 1943 purse seiner vessel owners on the Puget Sound agreed to subtract diesel costs from gross profit and then divide it into equal parts. Two shares were kept by the owner, two paid for the gear, and one share each went to the crew and the captain.

The California and Oregon reorganization projects raised difficult questions about the role and function of the International. In 1940, the IFAWA Secretary-Treasurer wrote that “The organizational work on Puget Sound has at last been built to a point where it can be said that we have in this district a form of industrial organization.” However, he continued, “It remains for this convention to take action to consolidate the strength of the International affiliates in the Puget Sound area into a type of coordinated body that can give to all groups their proper strength in the economic and legislative problems being faced.”[61] IFAWA chose its organized all gears and stages of fishing and canning on the basis of industrial unionism, but fell short in functioning as an industrial union. Structurally, Puget Sound was a patchwork of direct IFAWA locals, the United Fishermen’s Union and the Alaska Fishermen’s Union. All were vertically connected to IFAWA, but horizontal ties between the units were lacking. Overtures about unity between cannery workers and fishermen abounded, but proved difficult to implement in practice.[62] Nevertheless, the degree of unity far exceeded the system used by the International Seamen’s Union. Its successor, the Seafarer’s International Union, continued to use a setup in which small and geographically bounded unions affiliated directly with the International without mechanisms to coordinate coastwise or on the basis of craft or industry.

Supporters of a strong International argued that only such a body could lead to price stabilization through joint negotiations, coordination of demands and simultaneous action. The UFU-Puget Sound, which included Jurich, Dale and other important leaders of the International, was one of the strongest supporters of this theory. An effort to improve unity was launched at the 1940 IFAWA Convention, leading to the establishment of the Washington State Fishermen’s Council.[63] The Council became an important venue for information sharing and brought fish and cannery leaders into closer communication, but failed to become a space for decision-making or joint action. [64] Dale, head of the United Fishermen’s Union in Puget Sound and an International Board member, became President of the new group and IFAWA Secretary-Treasurer George Lane doubled as Secretary-Treasurer of the Council. This did little to dispel any feelings among smaller and rural locals that the Council was a method of centralizing and extending the control of the International and the UFU.[65] Tensions manifested in 1942, when the reefnetters, a direct IFAWA local, mounted a sustained effort to fire the International’s at-large Puget Sound organizer Kaare Paulsen. They felt he spent inadequate time on small locals that did not belong to the UFU. [66]

Unity was easier on the legislative front, where common issues were less fraught with issues of jurisdiction and internal politics. In the early 1940s, IFAWA pushed for fishermen to have access to social services. Due to misclassification, fishermen were excluded from the bulk of New Deal welfare legislation, including unemployment benefits. IFAWA chose the share system instead of hourly payment because it generally meant better earnings, but it also allowed boat owners to call the crew ‘partners’ instead of employees and not pay unemployment premiums.[67] IFAWA actively lobbied the Washington State Legislature for rule changes, and filed grievances with the State Unemployment Commission requesting prosecutions of vessel owners when crew filed for benefits only to find that no premium had been paid. The fight heated up in the post-war period, when boat owners moved to permanently bar crew access to benefits.[68] The union was also legislatively active in advocating for better funding of regulatory bodies like the Bureau of Fish and Wildlife. In 1939 four government employees based in Seattle were tasked with the scientific monitoring of fish on the entire Alaskan coast.[69] Often, regulatory agencies were funded exclusively by taxes on packers, which the union felt compromised impartiality.[70] IFAWA consistently demanded greater public funding of these agencies to expand their scope and independence. In the meantime, they lobbied to overturn regulations they thought were based on limited research. Finally, efforts to improve regulation of industrial pollution near waterways continued.[71] In 1943, lobbying efforts were expanded when organizer Oscar Rodin served as a full-time representative in Olympia during the legislative session.[72] This ability to operate in workplace, community and political spheres demonstrates the maturation of IFAWA following its 1939 formation.

[1] Minutes, Herring Fishermen’s Union of the Pacific February 17, 1938, box 6, folder 2; Minutes, Herring Fishermen’s Union of the Pacific March 3, 1938, box 6, folder 2.

Special Meeting Minutes, Herring Fishermen’s Union of the Pacific, March 10, 1938, box 6, folder 2; Salmon Purse Seiners Union All Agents, March 11, 1938, box 3, folder 2; Salmon Purse Seiners Union Executive Board , March 21, 1938, box 5, folder 10;United Fishermen’s Union-Puget Sound Pro Tem Secretary-Treasurer Jurich to All Locals, April 5, 1938, box 3, folder 2.

[2] Alaska Purse Seiner’s Union Convention September 11, 1937. box 11

[3] Second Annual Federated Fishermen’s Convention, San Francisco December 12-19, 1938, box 12, folder 22, 5-7; 10

[4] Ibid., 10.

In 1936, the SPSU aided Tacoma longshoremen by donating fish during their strike: Salmon Purse Seiner’s Union Executive Board, March 26, 1937, box 5, folder 10.

[5] Ibid., 27-38

[6] Second Annual Federated Fishermen’s Convention, box 12, folder 22.

[7] Pinsky, The Fisheries of California, 80-82; Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union Annual Convention, Tillamook, Oregon, January 5- 11, 1939, box 4, folder 38; First IFAWA Convention. Bellingham, WA, December 4-8, 1939, American Labor Unions Constitutions and Proceedings: Part I, 1836-1974, 11.

[8]Ibid., 19; 27; Gladstone and Jamiesom, “Unionism in the Fishing Industry of British Columbia,” 166.

[9] See, for e.g.: Proceedings, Second Convention IFAWA, December 9-13, 1940, box 12, folder 2, 21.

[10] North and Griffin. A Ripple, A Wave: The Story of Union Organization in the BC Fishing Industry. Fishermen’s Publishing Society, 1974. Page 19; Alan Haig-Brown, Fishing for A Living (Madeira Park:Harbour Publishing),104.

[11] Arnold, The Fishermen’s Frontier, 154-5, concurs with the self-identification of workers, citing: Lauren Casaday. Labor unrest and the labor movement in the salmon industry of the Pacific Coast. Thesis (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1937)

[12] See, for e.g.: J. Stephen Thomas, David Johnson and Catherine Riordan, “Independence and Collective Action: Reconsidering Union Activity among Commercial Fishermen in Mississippi” Human Organization 54, No. 2 (1995); E. Paul Durrenberger, “Psychology, Unions, and The Law: Folk Models and the History of Shrimpers ' Unions in Mississippi” Human Organization, Vol. 51. No. 2, 1992; On self-reliance, workplace control and working class identity, see: Reports from Labor, August 1, 1950, Jerry Tyler Papers, <https://depts.washington.edu/dock/tyler_audio/August_1_1950.pdf>.

[13] In 1936, the Italian Fishermen’s Association in San Pedro sought an injunction against SPSU closed shop agreements. Salmon Purse Seiners Union Executive Board, November 30, 1936, box 5, folder 10.

[14] Second Federated Fishermen’s Council Convention, box 12, folder 22, 9

[15] IFAWA Executive Board, April 16, 194, box 12, folder 14, 8-14

[16] Merger Convention, December 6-12, 1937, box 6, folder 4, 3.

[17] RaeJean Hasenoehrl, Everett Fishermen (Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2008), 16.

“Bellingham News Notes,” IFAW, December 1946, 9.

[18] Ibid.

See also: “Our Story,” Pure Alaska Salmon Industry Co. <http://www.purealaskasalmon.com/our-story-pure-alaska-salmon-company>. Note that one of the Zuanich family’s seiners, still in operation, is named the ‘Marshal Tito.’

[19] Minutes, Fifth Annual Convention, Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union, Astoria, Oregon, January 5-15, 1938, box 4, folder 38; Federated Fishermen’s Council Conference, Executive Committee, box 12, folder 22: February 2, 1-3.

[20] Executive Board Meeting, July 26, 1939, box 1, folder 9; Federated Fishermen’s Council Executive Board May 5, 1938. box 12, folder 22; Second Annual Federated Fishermen’s Council, box 12, folder 22. Page 11

[21] Fisheries of California, 69

[22] Ibid., 58-64

[23]Working Agreement for Salmon Purse Seine Boats July 1943, box 3, folder 10; Salmon Purse Seiners Union of the Pacific, Second Convention, December 1, 1937, 84 Seneca St, Seattle, Purse Seiners Hall. box 5, folder 1, page 26; First Annual Convention Federated Fishermen’s Council of the Pac Coast. Astoria, December 13-18 1937. box 12, folder 21, page 38; United Fishermen’s Union of the Pacific, Puget Sound District, Northwest Conference, Nov 28, 1938, box 5, folder 1, page 4; IFAWA, Pacific District Local 3 Executive Board April 6, 1946, box 12, folder 11. Page 1; Minutes of the First Annual Conference of the Pacific District Local No. 3, December 20, 1946, box 12, folder 11, page 4; Local 3 Executive Board February 19, 1949. box 12, folder 10, page 14

[24] Working Agreement for Salmon Purse Seine Boats July 1943, box 3, folder 10; Local 3 Executive Board February 19, 1949. box 12, folder 10, page 14; Local 3 Executive Board May 28, 1949. box 12, folder 10, page 4

[25] 1940 United Fishermen’s Union Convention, Report by Paul Dale, Secretary-Treasurer, box 1, folder 1.

[26] United Fishermen’s Union Northwest Conference November 27, 1939, box 3, folder 2, page 5; United Fishermen’s Union- Puget Sound Executive Council May 1, 1943, box 5, folder 1, page 2; Reports from Oscar Rodin, IFAWA Puget Sound representative, 1942, Lummi Island Heritage, http://content.statelib.wa.gov/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lummi/id/1031/show/1021/rec/20; Exhibits presented in the PSRN #4 case against Paulsen, 1942, Lummi Island Heritage, <http://content.statelib.wa.gov/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lummi/id/921/show/913/rec/7>

[27] Reports from Oscar Rodin, IFAWA Puget Sound representative, 1942. Lummi Island Heritage.

[28] Everett Local 3. July 6, 1939, box 1, folder 8.

Working Agreement for Salmon Purse Seine Boats July 1943. box 3, folder 10. Page 2

[29] August 30, 1937 Jurich to Boat Delegate. box 5, folder 15

[30] 1940 United Fishermen’s Union Convention, Report by Paul Dale, Secretary-Treasurer, box 1, folder 1.

[31] Paul Hummasti, Finnish Radicals in Astoria, Oregon, 1904-1940: A Study in Immigrant Socialism (New York: Arno Press, 1979).

[32] House Un-American Activities Committee, “Report on the American Slav Congress and Associated Organizations,” June 26, 1949, page 74; John Kraljic, “The Croatian Section of the Communist Party of the United States and the United Front: 1934 - 1939.” Croatian Institute of History. 2009.

[33] “Tamburitza,” Croatian Heritage, <http://www.croatians.com/EVENT-TAMBURITZA.htm>

“Thumbnail Sketch of a Union Leader,” IFAW, September 1948, 8.

[34] “Paul Dale Veteran Leader of UFU Dies” IFAW, June 1944, 5; House Un-American Activities Committee, “Investigation of Communist Activities in the Pacific Northwest Area.”

[35] Previously named the Alaska Canned Salmon Industry before changing to ASI; United Fishermen’s Union Northwest Conference November 27, 1939, box 3, folder 2, pages 3-4

All-Alaska Labor Convention, January 12-15, 1940, box 5, folder 1; Statement of Policy of the Labor Coordinating Committee, The Alaska Salmon Industry, November 24, 1943, box 3, folder 32

[36] Agreement, April 14, 1938, box 3, folder 32

[37] First IFAWA Convention. December 4-8, 1939, Pages 13-14

[38]Anacortes Local 2, June 29, ’39. box 1, folder 8; UFU-PS District Northwest Conference November 27, 1939. box 3, folder 2. Page 5

[39] Ibid., NE Mason, page 6.

[40] First IFAWA Convention, page 12; Report of Nick Mladinich, Second Annual Convention of the United Fishermen’s Union, December 11-14, 1939, box 4, folder 38

[41] First IFAWA Convention, page 12; 36

[42] Minutes of California District Executive Board Meeting, January 5, 1939, box 2, folder 30; First IFAWA Convention, page 66-9; Fisheries of California, 83

[43]“Packers Hit Tuna Fishermen by Injunction,” Washington New Dealer. July 13, 1939. Pages 1, 3

[44] 4th Convention, December 1-4 1942, Seattle. box 12, folder 2. Page 12

[45] First IFAWA Convention. Bellingham, WA December 4-8, 1939. Page 43

[46] Yearbook Second Convention IFAWA. December 9, 1940. Astoria, OR. box 12, folder 2. Page 12.

[47] IFAWA Executive Board April 16, 1941. box 12, folder 14. Page 8; Proceedings, Second Convention, December 9-13, 1940. box 12, folder 2. Page 79

[48] Proceedings Third Convention, December 1-5, 1941 San Francisco. box 12, folder 2. Page 15; 23-4

[49] Minutes of Drag Boat Fishermen’s Meeting October 19, 1940. box 18, folder 30; Proceedings Third Convention, December 1-5, 1941 San Francisco. box 12, folder 2. Page 15; IFAWA Executive Board April 16, 1941. box 12, folder 14. Page 8.

[50] “Kibre Blast Red-Baiting,” IFAW. December 1947, page 3.

[51] David Scott Witwer, Shadow of the Racketeer: Scandal in Organized Labor, page 121-2; 288

[52] All-Alaska Labor Convention, sponsored by the Maritime Federation of Pacific, Juneau, Alaska, January 12-15, 1940. box 5, folder 1. Pages 10-11

[53] All-Alaska Labor Convention, sponsored by the Maritime Federation of Pacific, Juneau, Alaska, January 12-15, 1940. box 5, folder 1; Proceedings, Second Convention, December 9-13, 1940. box 12, folder 2. Pages 11-13

[54]Directory, Yearbook Second Convention IFAWA. December 9, 1940. Astoria, OR. box 12, folder 2. Page 18

[55] Proceedings, Second Convention, December 9-13, 1940. box 12, folder 2. Pages 9-14.

[56] Proceedings Third Convention, December 1-5, 1941 San Francisco. box 12, folder 2. Page 17

[57] For a discussion of the various formulas to calculate ‘per capita’ (not actual) membership and their varying degrees of accuracy vis a vis total membership, see: Proceedings Third Convention, December 1-5, 1941 San Francisco. box 12, folder 2. Page 8, 25

[58] Proceedings Third Convention, December 1-5, 1941 San Francisco. box 12, folder 2. Page 13

[59] UFU-PS Conference November 22, 1941. box 3, folder 2

[60] Sardine Working Agreement 7/18/40. box 3, folder 18; Working Agreement for Salmon Purse Seine Boats July 1943. box 3, folder 10; Wick, Ocean Harvest, 175; Other examples of contracts: Tendermen’s Agreement 1946. box 3, folder 23; Herring Agreement June 23, 1942 (Renewed for 1943). Fish Reduction and Saltery Plants operating in Territory of Alaska (‘Company’) and UFU-PS. box 3, folder 10.

[61] “Secretary Treasurer [George Lane] on the Role of the International,” Yearbook Second Convention IFAWA. December 9, 1940. Astoria, OR. box 12, folder 2. Pages 4-5

[62] Proceedings, Second Convention, December 9-13, 1940. box 12, folder 2. Page 62.

[63] Proceedings, Second Convention, December 9-13, 1940. box 12, folder 2. Page 59.

[64] UFU Bulletin May 1941, No. 6; UFU Bulletin. April 1941, No. 5

[65] Washington State Fishermen’s Council, UFU Hall, February 16 1941. box 12, folder 14

WA State Fishermen’s Council March 28, 1942. Attached to: UFU-PS Executive Council April 4, 1942. box 3, folder 2; UFU-PS Executive Council June 5, 1943. box 5, folder 1

[66] Proceedings Third Convention, December 1-5, 1941 San Francisco. box 12, folder 2. Page 16; Exhibits presented in the PSRN [Puget Sound Reefnetters] Local #4 case against Paulsen, 1942.; http://content.statelib.wa.gov/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lummi/id/921/show/913/rec/7; Reports from Oscar Rodin, IFAWA Puget Sound representative, 1942. Lummi Island Heritage.

[67] Jurich to Houghton, Cluck & Coughlin, March 8, 1946. box 14, folder 1

[68] IFAWA Pacific District Local 3 Conference December 17, 1948. box 7, folder 1. Page 3

[69] Cooley, Politics and Conservation: The Decemberline of the Alaska Salmon Industry. Page 153.

IFAWA Views the News. Aug 15, 41. 1, 4

[70] First IFAWA Convention. Bellingham, WA December 4-8, 1939, Labor Union Constitutions and Proceedings.

[71] UFU Bulletin March 41, No. 4

[72] January 23, 1943 letter from Martin Hegerberg, Lummi Island Heritage.