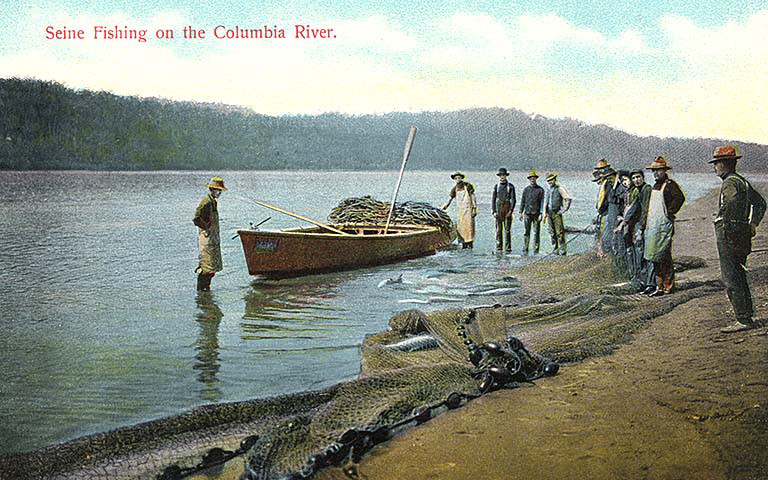

Seine fishing Columbia River (UW Library Digital collection)

This essay is presented in five chapters.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Early Unionism in the Pacific Coast Fisheries

Chapter 3: A Coastwise, Industrial Union

Chapter 4: World War II

Chapter 5: Struggle, Strikes and Collapse

Leo Baunach's essay won the 2013 Library Research Award given by University of Washington Libraries.

Cannery workers filling tuna cans, Long Beach, date unknown

(UW Libraries digital collections)

by Leo Baunach

Unionism in the West Coast commercial fishing and canning industry has a long history, though until industrial unionism in the 1930s it was constrained by craft, geographic and racial divisions.[1] The first union began on the Columbia River in the 1870s, not long after the first cannery was established in 1867.[2] The Fishermen’s Benevolent Aid Society was formed in 1875 to pool money for burials and exclude Chinese immigrants who worked in the canneries from expanding into fishing. Leaders of the Society went on to form the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union (CRFPU) in 1880, which affiliated with the American Federation of Labor and led a major 1896 strike that was crushed by the National Guard. From this defeat grew a cooperatively owned cannery that successfully operated until 1950.[3] Between 1896 and 1926, the CRFPU underwent several cycles of decline and reorganization. Craft unionism and racial exclusivity limited its success.[4]

Meanwhile in 1902, 700 non-resident fishermen from San Francisco and Seattle staged a wildcat strike aboard company-owned boats while fishing near Bristol Bay, Alaska. A promised pay increased never manifest, but the dispute led to the formation of the Alaska Fishermen’s Union. By 1904 it had 5,000 members and affiliated with the International Seamen’s Union-AFL (ISU). [5] For the next three decades, it was the strongest fishermen’s union on the Coast. [6] A similar union, the Copper River and Prince William Sound Fishermen’s Union, formed a few years later and joined the ISU.

Communists and the Great Depression

In the early 1930s, two factors dramatically altered fishery worker unionism on the West Coast. First, fish prices dropped dramatically in 1931. Secondly, industrial unionism spurred organization on a grander scale. The idea of coastwise union to represent all workers from catch to cannery was introduced by a Communist Party-led union, the Fishermen and Cannery Workers Industrial Union. It did not create such an organization in its short existence, but created the networks which built the International Fishermen and Allied Workers. First though, the 1931 price drop led to wildcat strikes and the reinvigoration of old unions. Strikes generally took the form of ‘tie-ups,’ so called because the fishermen left their boats tied to the dock until a settlement was reached. The actions were often defensive, taken against packers that were providing lower prices than their competitors, and were often short in duration.[7]

The Fishermen and Cannery Workers Industrial Union (FCWIU) was launched in 1931 as a project of the Trade Union Unity League, a Communist Party-led effort to build independent unions outside of the AFL. The mostly unorganized and disgruntled workforce of the fishing and cannery industry proved fertile ground. The first big success came in 1931 when leftist dissidents gained control of the Vancouver, Canada local of the British Columbia Fishermen’s Protective Association.[8] The local was expelled and purse seine fishermen throughout British Columbia joined them to form four locals of the Communist FCWIU.[9] Like other fishing unions, they faced tough resistance from packers who would alter prices in response to pressure but were loathe to sign agreements. The Canadian Fishermen and Cannery Workers successfully signed one contract around 1935 with the Deep Bay Packing and Fishing Company, but it was abrogated two years later when the cannery burned.[10] Meanwhile, FCWIU organizers were busy in the Puget Sound and Columbia River building a network of workers and agitating within existing unions. This dual-union strategy mixed pre- and post-1929 Communist Party approaches to labor organizing.[11]

On May Day 1933, the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union called a strike of gillnet fishermen in Astoria and the Lower Columbia. Between 2,500 and 4,000 fishermen ceased working and shut down operations in the area. In the Upper River area, a majority joined the strike.[12] Within days, roughly 1,000 cannery workers walked out in support. To show support, the Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union (PCFU), formed by the International Seamen’s Union in 1932 to capitalize on the upsurge of unrest in the industry, tied-up salmon trolling vessels in Puget Sound and Alaska. Trollers in the radical Fishermen and Cannery Workers in British Columbia followed suit.[13] For the first time, fishermen across craft and watershed lines were gaining a sense that their struggles intersected. The sympathy strike was also strategic move by the troller fishermen. Following the settlement of the Columbia dispute, 4,000 American and Canadian trollers, including 600 in Puget Sound, struck.[14] Within a week, they settled contracts with companies in Vancouver, BC and Astoria, Oregon that returned the majority of the fleet to work. Packers in Seattle refused to settle, so the trollers simply redirected deliveries to the other ports.[15]

The other base of support for the Fishermen and Cannery Workers Industrial Union was in San Pedro, where it became part of the radical ferment that exploded in the 1934 maritime and longshore strike. In fact, the FCWIU was the first group of workers to go on strike in the Los Angeles harbor in 1934, tying up San Pedro, Wilmington and Long Beach for a week in January.[16] It also led a raucous organizing drive at a Van Camp cannery in San Diego that culminated in a lockout and violent clashes with police in May 1934, against the backdrop of the longshore strike.[17] In July, San Pedro fishermen enthusiastically pledged their support for a general strike after Blood Thursday.[18]

The Communist Party shifted its strategy in 1935, opting for a popular front alliance with liberals. The Trade Union Unity League and its affiliates were dissolved. Former locals of the Fishermen and Cannery Workers (FCWIU) quickly regrouped into localized craft unions. The Salmon Purse Seiner’s Union (SPSU) was formed to regroup the FCWIU locals in British Columbia and the network of sympathizers on Puget Sound. In Washington State, the Herring Fishermen’s Union was also formed. The new units applied for affiliation with the International Seamen’s Union (ISU), part of the American Federation of Labor. The International was acutely aware of the leftist foundations of the applicants and stalled the process for several months. Conrad Espe, Secretary-Treasurer of the Salmon Purse Seiners, lobbied for the admission of the two new unions in Washington.

Meanwhile, his union underwent an enormously productive period of organizing. In spring 1935, the SPSU had locals in Tacoma, Anacortes and Bellingham. By July, there were new locals in Seattle and Everett, and membership stood at around 800. This represented 60% of the Sound salmon purse seiner workforce.[19] Union headquarters were established in South Bellingham, an ideal location for the union to put down roots community roots that went beyond the workplace.

The strength of the SPSU in South Bellingham and the FCWIU in San Pedro, both Croatian strongholds, draws attention to the importance of Yugoslavians in the move toward industrial unionism in fishing. The first SPSU strike was called in July and members stayed home during the start of the Sound salmon season. There were no picket lines, but the silence on the docks contrasted to the festive atmosphere that normally accompanied the first day of the season. More than just a labor dispute, it was a collective community refusal to live at the whims of the packers. The fishermen were highly skilled workers with a knowledge of the fishing grounds and salmon that could not be taught, making it difficult to recruit replacement workers on short notice. 454 members participated in the strike authorization vote, including a massive turnout of 235 at a meeting in Tacoma. The action bore fruit later in August when the SPSU signed its first contracts.

Toward a united fisherman's union

I argue that the leadership of Fishermen and Cannery Workers Industrial Union consciously thought of dissolution as a strategic move, and planned from the beginning to build a new and united fishermen’s union within the shell of the International Seamen’s Union.[20] A call for a conference of all West Coast union fishermen was endorsed at the first SPSU convention in December 1935.[21] Espe immediately went to work on the idea. During the effort to gain admission to the Seamen’s Union, he built relationships with existing affiliates like the Alaska Fishermen’s Union. An invitation to the January 1936 Seamen’s Union Convention gave him an additional opportunity to conduct outreach. There, the Salmon Purse Seiners, Herring Fishermen, and the union of former FCWIU locals in California were admitted to the International. A resurrected Copper River and Prince Williams Sound Fishermen’s Union was readmitted under an old charter.

Though the key goal of admission was achieved, the ensuing Convention was a disaster. It was the first Seamen’s Union Convention since 1930, and was to be the last. The ISU had been virtually inoperable since the early 1920s when membership shrank by more than 100,000 and it lost the ability to control the conditions of seafaring work. Political, personal and geographic factionalism thrived. At the 1936 Convention, the newly admitted fishermen caucused with a group of West Coast progressives that, although outvoted 2-1, could block any motion.[22] Espe left two weeks into the marathon convention when he secured funds to travel to San Pedro to assist in an organizing drive.[23]

1936 continued to be a tumultuous year for the Salmon Purse Seiners Union. In June the union signed its first closed shop agreement, which guaranteed that a cannery would only buy from SPSU fishermen at an agreed-upon price. The victory proved to be ephemeral when a weak salmon run forced many to fish for pilchard instead of salmon. In fall, they were locked out by salmon packers, but the SPSU held strong for the entire season and refused to settle.[24] Workers may have fished for other catches or taken non-fishing jobs during this time. Reflecting after the close of the season, union officials concluded that “the buyers themselves still do not realize the strength of the fishermen’s union or organized labor, and our action this fall has again proved to those who control the industries that they are not the sole bosses. It is admittedly true that the purse seine fishermen lost some money, but they have gained enough in prestige to make up in the coming season for what they have lost and more.”[25]

Meanwhile, the situation in cannery unionism heated up when leaders of the Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union Local 18257 (CWFLU), which represented Filipino non-resident cannery workers who worked in Alaska, were mysteriously murdered in December. Espe was increasingly involved in the CWFLU, resigning from the Salmon Purse Seiners in August 1937. He would later become an International Vice-President of the CIO’s United Cannery, Agricultural, Packinghouse and Allied Workers of America.[26] His resignation cleared the way for Joseph Jurich, Business Agent from Tacoma, to become Secretary-Treasurer of the SPSU. Astoria-born Communist Party organizer Paul Dale continued to head the Herring Fishermen’s Union.

Membership in the International Seamen’s Union (ISU) granted the ex-FCWIU unions the legitimacy needed to assume a position of leadership among the disparate fishery unions of the Pacific Coast. Further, the deterioration of the Seamen’s Union into a paper entity after the Convention ensured that there was no interference with their efforts. An ISU Fishermen’s Unions Conference was held December 7-8, 1936 and a constitution was drafted for a Federated Fishermen’s Council of the Pacific, ISU-AFL (FFC). Matt Batinovich, Business Agent of the Deep Sea and Purse Seine Fishermen’s Union, an outgrowth of the FCWIU in California, was elected President. Martin Olsen of the Alaska Fishermen’s Union was selected as Secretary-Treasurer, cementing unity between the newly admitted unions and longtime ISU affiliates.[27] The preamble of the Constitution was remarkable, showcasing an awareness of ecological issues and a commitment to working class struggle. It is worth quoting at length:

[We commit to] justly share the products of our labor…dedicate ourselves to the conservation of natural resources and maintenance of the fisheries through artificial propagation and elimination of destructive agencies. We deplore selfish and wanton waste and unreasonable demands on our fisheries’ resources. Knowing that we are at all times dependent on the well-being of our fellow men, that we may share in the production of our industry only in direct proportion to our ability to control the operations within the industry, and that it does not in itself suffice that we establish efficient leadership, but that each and every member must become conscious of his importance to the welfare of the whole industry and carry on with a willing and unselfish spirit in maintaining the welfare of the many, it shall be our wish to aid all laboring people to better their conditions to the common end that all laboring people may enjoy the fruits of their labor. We are aware that our struggle for economical betterment carries with it the responsibility of bettering our political and social conditions.[28]

Batinovich’s union was joined by the Alaska Fishermen, Salmon Purse Seiners, Herring Fishermen, the Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union, and the Copper River and Prince William Sound Fishermen’s Union as founding members of the Council. The Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union and the Deep Sea Fishermen’s Union, which represented halibut fishermen out of Seattle, chose not to join but maintained friendly relations with the new body.[29] The combined membership of the Council was around 12,000.[30] At the meeting, they discussed common struggles with obstinate packers, ethnic divisions that undermined unionism and the lack of coordination between unions. The Conference also featured a productive discussion with the Inlandboatmen’s Union, another ISU affiliate, which agreed to relinquish jurisdiction over fish cannery workers in favor of the Council.[31]

Federated Fisherman's Council Constitution

The formation of the Federated Fishermen’s Council greatly facilitated coordinated collective bargaining. The Salmon Purse Seiners Union and the Herring Fishermen’s Union jointly negotiated contracts with vessel owners concerning on-board conditions, and the Deep Sea and Purse Seine Fishermen’s Union negotiated with Monterey-based packers on behalf of the Herring Fishermen. All three unions signed a master contract with both vessel owners and cannery companies covering the sardine catch.[32]

In July 1937, the newly formed FFC Executive Board dispatched Batinovich and Olsen to a meeting of the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO). The CIO was beginning the difficult task of building a full labor federation, after its main affiliates were expelled from the AFL in fall 1936. At the meeting, CIO leaders floated the idea of a charter for fishermen, and longshore leader Harry Bridges attended a meeting of the Federated Fishermen’s Council afterwards to advocate for CIO membership. In the wake of another CIO meeting in August, the Fishermen’s Council asked its affiliates to conduct referendums on affiliation. The vote was stalled because of the fall fishing season and political maneuvering between pro-AFL and pro-CIO factions.[33]

Meanwhile, the Deep Sea and Purse Seine Fishermen’s Union, the Salmon Purse Seiners and the Herring Fishermen -- all derived from the Communist FCWIU -- voted to merge. They amalgamated shortly before the Federated Fishermen’s Council Convention in December 1937, thereby consolidating the most pro-CIO sectors of the Council and creating a coastwise, multi-catch union of seine fishermen.

The newly created United Fishermen’s Union of the Pacific (UFU) was technically still a craft organization of seine workers, but was a crucial step toward industrial unionism. Commemorating Emil Linden, first Secretary of the FCWIU, the United Fishermen’s merger convention approved a resolution vowing that fishermen would “soon be united in one powerful coastwise union as visioned by Brother Linden.”[34] At the Council Convention, the feeling was generally pro-CIO, and affiliation enjoyed the endorsement of Vice-President and Alaska Fishermen’s Union member Martin Olsen. A renewed call was made for internal ballots among Federated Fishermen’s Council affiliates on the question of CIO membership.[35] At the end of the Convention, Batinovich declined nomination for another term as head of the FFC, likely because he was first in line to lead the United Fishermen’s Union. This cleared the way for Joe Jurich to take over as leader of the Fishermen’s Council. Industrial unionism was moving from an aspirational concept put forward by a scattered Communist Party union to an actionable form of organization supported by most Pacific Coast fishermen.

[1] George North and Harold Griffin, A Ripple, A Wave: The Story of Union Organization in the BC Fishing Industry (Vancouver, BC: Fishermen’s Publishing Society, 1974), 9.

[2] “Fishermen’s Union Grows Old on Good Ideas” IFAW, January 1948, 4. N.D. Jarvis, “Curing and Canning of Fishery Products: A History,” Marine Fishery Review 50, no. 4 (1988): 183

[3] Greg Jacob, “Union Fishermen's Cooperative Packing Company,” Oregon Encyclopedia. http://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/entry/view/union_fishermen_s_cooperative_packing_company/. “Columbia River Fisheries,” Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union (Astoria, OR: G.W. Snyder, 1890). Available via University of Washington Digital Collections, http://content.lib.washington.edu/u?/salmon,318. “Fishermen’s Union Grows Old on Good Ideas” IFAW, January 1948, 4.

[4] Ibid.,

Henry Niemela, “Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union,” in ‘Yearbook Second Convention IFAWA, 1940,’ box 12, folder 2, page 11.

[5] Andrew Vigen, “Alaska Fishermen’s Union – Early History” in ‘Yearbook Second Convention IFAWA, 1940,’ box 12, folder 2, page 9.

[6] Pinksy, The Fisheries of California: The Industry, the Men, Their Union, 75-6.

Martin Hegeberg, “Vice President on the Benefits of Affiliation,” in ‘Yearbook Second Convention IFAWA, 1940,’ box 12, folder 2, page 6

[7] Pinsky, The Fisheries of California, 77. North and Griffin, A Ripple, A Wave, 9.

[8] Percy Gladstone and Stuart Jamiesom, “Unionism in the Fishing Industry of British Columbia,”

The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 16, no. 2 (1950): 162.

[9] Ibid., 163

[10] “Shoreworkers and the UFAWU Organization” in Uncommon Property: The Fishing and Fish-Processing Industries in British Columbia, Patricia Marchak, Neil Guppy and John McMullan ,eds (Toronto: Metheun 1987), 272. North and Griffin, A Ripple, A Wave, 19.

[11] “Fishermen Win Strike, Will Get Demand of 8 cents,” Voice of Action, June 14, 1933, 1. “55 Columbia River Cannery Workers and Fishermen Meet,” Voice of Action , March 13, 1934. For some scant details on TUUL organizing among Puget Sound fishermen, see: House Un-American Activities Committee, “Investigation of Communist Activities In the Seattle, Wash., Area,” March 17-18 1955, 262-7.

[12] “Strike Demands Refused; Salmon Plants to Close” Seattle Times, May 4, 1933, 13. “Fishermen’s Strike Spreads North: Packers and Netters Refuse Peace” Lewiston Morning Tribune, May 7, 1933.

[13] Gladstone and Jamiesom, “Unionism in the Fishing Industry of British Columbia,” 164.

[14] “Fishermen Win Strike, Will Get Demand of 8 cents,” Voice of Action, June 14, 1933, 1.

“Fishermen Will Return to Work; Boycott Seattle.” Seattle Times, June 22, 1933.

[15] Ibid.

[16] "Pedro Sardine Fishermen on Strike Under FCWIU,” Voice of Action, January 22, 1934, 3.

"San Pedro Fishermen Win Strike Under Leadership of the FCWIU,” Voice of Action, January 29, 1934, 2. Todd Titterud, “January in San Pedro,” My San Pedro, January 8, 2011. http://www.mysanpedro.org/2011_01_01_archive.html>

[17] Rudy Guevarra Jr., Becoming Mexipino: Multiethnic Identities and Communities in San Diego ( New Brunswick : Rutgers University Press, 2012.), 120-1.

[18] “Fishermen Ready to Join Strike,” Seattle Times, July 7, 1934.

[19] ‘Conrad Espe to Victor Olander, Secretary, ISU, letter, July 25, 1935, box 5, folder 14

Olander to P.B. Gill, telegram, July 25, 1935, box 5, folder 14. R.H. Fiedler, Fishery Industries of the United States 1937, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1938), 372.

[20]Espe to Jurich, letter, January 19, 1936, box 5, folder 11. Jurich to Espe, letter, box 5, folder 11

There is no ‘smoking gun’ showing a plan, but the close personal friendship between Espe, Jurich, Dale, George Ivankovich (San Pedro) and other Party members/union leaders is apparent, and they discuss the plans for a fishermens conference in these letters during the Convention. The sustained efforts of former FCWIU leaders to tie together fishermen’s unions and eventually join the CIO strongly suggested it was concerted and intentional.

[21] Conrad Espe to Andrew Vigen, Secretary, AFU, letter, December 13, 1935, box 5, folder 14

[22] Hyman Weintraub, Andrew Furuseth: Emancipator of the Seamen (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1959), 191-9.

[23] Espe to Jurich, letter, January 19, 1936, box 5, folder 11. Espe Report on 33rd ISU Convention, box 5, folder 11

[24] Salmon Purse Seiners Union ExecutivExecutive Board, October 24, 1936, box 5, folder 15

‘Salmon Purse Seiners Union of the Pacific, Second Convention,’ December 1, 1937, box 5, folder 1.

[25] Salmon Purse Seiners Union Executive Board, January 3, 1937, box 5, folder 10

[26]Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Local 7, Inventory, University of Washington Special Collections, http://www.lib.washington.edu/static/public/specialcollections/findingaids/3927-001.pdf. Meeting minutes, box 5, folder 6. Espe to Jurich, letter, August 10, 1937, box 12, folder 22. Salmon Purse Seiners Union Executive Board-Board, December 6, 1936, box 5, folder 10

[27] Minutes CIO National Maritime Unity Conference, Chicago August 30-September 1, 1937, box 12, folder 22

First Annual Convention Federated Fishermen’s Council of the Pacific Coast. Astoria, December 13-18, 1937, box 12, folder 21

[28] Federated Fishermen’s Council of the Pacific, ISU-AFL Constitution, box 1, folder 1.

[29] Pinsky, Fisheries of California, 79.

[30] First Annual Convention Federated Fishermen’s Council, box 12, folder 21. On shifting membership numbers and per capita, see, for e.g: Executive Board Meeting of Federated Fishermen’s Council, August 23-25, 1937, box 12, folder 22.

[31] International Seamen’s Union Fishermen’s Unions Convention, December 7 1936, box 1, folder 7

Salmon Purse Seiners Union Executive Board, January 17, 1937, box 5, folder 10.

[32] Minutes of the Negotiations Committee of the Herring Fishermen’s Union of the Pacific, Salmon Purse Seiners Union of the Pacific with the Pacific Coast Boat Owner’s Association, May 26, 1937, box 6, folder 2. Minutes, Herring Fishermen’s Union of the Pacific, May 13, 1937, box 6, folder 2. Minutes, June 7, 1937, Canners, Unions and Boat Owners Organizations, box 6, folder 2. Conference on the Working Agreement and Other Mutual Union Problems of DSPSFU, SPSU, HFU, Monterrey March 19, 1937; Conference on the Sardine Agreement, the Price of Sardines and Fishing Legislation. Attached to: SPSU HQ Mtg, Anacortes. July 24, box 5, folder 10

[33] Pinsky, Fisheries of California, 80.

Alaska Purse Seiner’s Union Convention, September 11, 1937, box 11.

[34] Merger Convention of the DSPSFU-CA, SPSU-Pac, HFU-Pac., Astoria, OR, December 6-12, 1937, box 6, folder 4.

Salmon Purse Seiners Union Executive Board, October 16, 1937, box 5, folder 10

[35] First Annual Convention Federated Fishermen’s Council of the Pac Coast. Astoria, December 13-18 1937, box 12, folder 21, 8; 11; 26;