Do you have any materials written by Elisabeth Miller? I work at the Carl S. English, Jr. Botanical Garden at the Ballard Locks, and I’m interested in comparing her approach to gardening with Carl English’s. Carl did not write much about his work, and I’m curious if I can learn more about him from other people’s work.

I want to learn more about Carl’s guiding ideas about horticulture so in the future we can continue to cultivate a garden that he could still recognize. I’m trying to pin down some concrete guidelines on what and how we add to the botanical collection here in the garden. The more information I have about and from Carl, the better I hope to answer this question.

It’s also interesting to juxtapose Betty and Carl’s careers and outputs. It helps me place his actions in the context of what was going on horticulturally during their working careers.

On the face of it, the two plant-lovers had very different approaches to gardening and life.

Betty (1914-1994) was an activist and advocate for public gardens and green space in the city, but her primary garden was and remains inside a gated community. As far as I know she never ran a business of any kind, although she worked with local nonprofit groups and believed in horticultural education. She was active in the Garden Club of America and the American Horticultural Society. One of her proud accomplishments was raising $40,000 for a comprehensive approach to planting the Lake Washington Ship Canal, a project that brought her into collaboration with the Army Corps of Engineers.

We have in our archives here several things Betty Miller wrote for publication:

- V. 53 issue 2, 1974, American Horticulturist article “Why Green Turns Brown.”

- Winter 1978 Arboretum Bulletin article “Challenge to Maintain the Green Scene.”

- 10/1979, American Forests magazine issue with article “Seattle’s Freeway Park” by Betty Miller.

- Summer 1982, “The Roots of the N.O.H.S,” by Betty Miller, reprinted from Horticulture Northwest.

- 1982 Puget Soundings article “There is Always a Garden.”

- Her chapter from Rosemary Verey’s 1984 book, The American Woman’s Garden, where she writes about her garden.

There is also an interesting list of biographical data on Betty Miller that I would guess she wrote herself in the late 80s or early 90s.

This 1996 article by David Laskin in the Seattle Weekly gets into more detail about Betty’s personality:

So does Ted Marston’s remembrance of her from the Autumn 1994 Garden Notes (a Northwest Horticultural Society publication). He spoke with Mareen Kruckeberg, Dick Brown, Steve Lorton, Michael Lynn and others about their memories of Betty.

Carl (1904-1976) moonlighted with his nursery business, and of course the gardens named for him at the Locks are a beloved public institution. He participated in plant exchanges with arboreta around the world and joined plant societies worldwide, including the American Horticultural Society, the Scottish Rock Garden Club, the Alpine Garden Society of England, and others. Native plants of this region were also of interest to him and his wife Edith; they botanized and contributed specimens to herbaria. On a personal level, he was said to be outdoorsy, friendly, and a valued member of groups. He gave lectures and led field trips to the mountains.

In our archives, you can read this article by Carl English:

- Summer 1972, “The Garden at the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks in Seattle,” American Horticulturist, 3 pp.

This promotional text he likely wrote as well:

- 4/1962, Locks brochure with cover photo of welcome sign and building (see “Seven Acres of Gardens” on the back, which Carl may have written himself.)

- 1969 “Green Palms” brochure.

Here is a piece about him written before he died in 1976:

- 9/1957, “Plantsmen in Profile, Carl S. English Jr.” by William J. Dress, rpt. from “Baileya,” 6 pp. (reprinted in Horticulture Northwest, vol. 11, no. 4, 1984 with a different picture of Carl)

We also have obituaries and remembrances of him.

HistoryLink has a couple of articles that may interest you. This is their perspective on Carl S. English, Jr. They also host this article, where Art and Mareen Kruckeberg count both Betty and Carl among their friends.

Ruscus has evergreen leaf-like structures called cladodes which are actually flattened modified stems that do the task of photosynthesis just as leaves would. The plant does have leaves, but these are non-photosynthetic and very inconspicuous. An

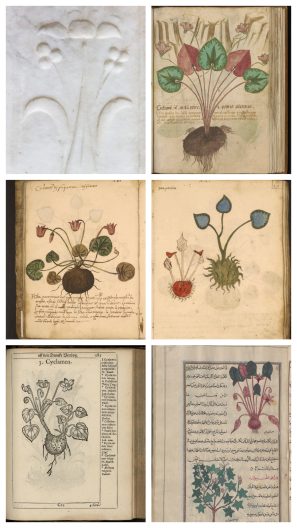

Ruscus has evergreen leaf-like structures called cladodes which are actually flattened modified stems that do the task of photosynthesis just as leaves would. The plant does have leaves, but these are non-photosynthetic and very inconspicuous. An  I also could not find evidence for cave paintings, but the name Cyclamen goes back much farther than Linnaeus’s time. It was Latinized from Greek kyklā́mīnos, and that word has ancient origins in the Greek for circle—probably because of the plant’s round tuber. The plant was introduced to cultivation in Western Europe from its native eastern Mediterranean region. There is supposedly a sculpted cyclamen in a house in Pompeii, but it is hard to recognize any of the plant’s distinctive characteristics.

I also could not find evidence for cave paintings, but the name Cyclamen goes back much farther than Linnaeus’s time. It was Latinized from Greek kyklā́mīnos, and that word has ancient origins in the Greek for circle—probably because of the plant’s round tuber. The plant was introduced to cultivation in Western Europe from its native eastern Mediterranean region. There is supposedly a sculpted cyclamen in a house in Pompeii, but it is hard to recognize any of the plant’s distinctive characteristics.

The Miller Library has Augustine Henry’s own copy of the seven-volume

The Miller Library has Augustine Henry’s own copy of the seven-volume