Are carnation and pink flowers edible? I read (in a novel) about a 17th century beverage called “Water of Venus” that included carnations and cinnamon.

I could not find any information about a beverage of that name, which may be the author’s invention. As long as the plants are grown without chemical fertilizers or pesticides, it should be safe to use spicy, clove-flavored Dianthus petals in drinks and edible concoctions, from cake and salad decoration to flavoring oils and vinegars. According to Edible Flowers: A Global History by Constance L. Kirker and Mary Newman (Reaktion Books, 2016), ancient Greeks and Romans used the petals in various dishes. The genus name is from Greek dios (god) and anthos (flower). The Romans called carnations Jupiter’s flower, to honor the god.

I could not find any information about a beverage of that name, which may be the author’s invention. As long as the plants are grown without chemical fertilizers or pesticides, it should be safe to use spicy, clove-flavored Dianthus petals in drinks and edible concoctions, from cake and salad decoration to flavoring oils and vinegars. According to Edible Flowers: A Global History by Constance L. Kirker and Mary Newman (Reaktion Books, 2016), ancient Greeks and Romans used the petals in various dishes. The genus name is from Greek dios (god) and anthos (flower). The Romans called carnations Jupiter’s flower, to honor the god.

John Gerard’s 1597 Herball mentions that “a water distilled from Pinks has been commended as excellent for curing epilepsy,” and more generally, “a conserve made of the flowers with sugar is exceeding cordial, and wonderfully above measure doth comfort the heart, being eaten now and then.” In Carnation (Reaktion Books, 2016), author Twigs Way lists varieties of intensely fragrant pinks that are ideal for adding to food and drink: ‘Mrs. Sinkins,’ ‘Doris,’ Whatfield Can-can,’ ‘Betty Norton,’ as well as ‘Giant Chabaud’ carnations.

The article “History and Legend of Carnation to 1800” by W. D. Holley (editor for the Colorado Flower Grower’s Association) gives an idea of the wide-ranging presence of the plant, including its use in Elizabethan times for spicing wine and ale, called sop-in-wine or wine-sop.

Garden author Gayla Trail offers a recipe for Dianthus-infused vodka on her You Grow Girl blog. There are more recipes in the Herb Society of America‘s guide for using clove pinks, including instructions on how to prepare the flowers (discard the white base of the petals as well as the sepals and styles which can be bitter).

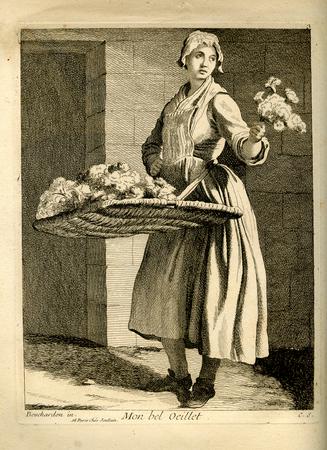

For more extensive historical information, Mary MacNicol’s Flower Cookery (Collier Books, 1972) is an excellent resource, with recipes from the 1600s to the 1900s. There is one recipe for Ratafia d’Oeillets from The Art of French Cookery (1814) by Antoine Beauvilliers. It calls for 24 pints of brandy and a pound of ratafia pinks (i.e., carnation flowers): “take nothing but the red of the flowers which is put into the brandy, with a drachm of bruised cloves; […] leave them a month in infusion; drain, and press the flowers well; dissolve two pounds of sugar in eight pints of water; mix it well with it; strain and bottle.” There is a second ratafia recipe using pinks with stamens removed, cinnamon sticks, saffron, strawberry juice, sugar, and brandy. Perhaps these beverages inspired the novelist’s Water of Venus.