by Randi Storch

The Communist Party of the United States was established in Chicago in 1919 by left-wing Socialist Party members who were inspired by the Bolshevik revolution. Through 1923, their members seemed to do little else but disagree over internal questions facing their organizations. Between 1928 and 1935, however, Chicago’s Communist Party experienced its first exponential growth in membership, tens of thousands turned out for Communist rallies and the city’s Communists developed lasting structures in its neighborhoods and factories. In these years, Communists learned to work with liberals and non-Communists: they developed successful organizing tactics and fought for workers rights, racial equality, unemployment relief and against imperialism. Party members believed that capitalism had moved into its “Third Period” of development and that capitalism’s collapse and imperialism’s end were certain. To that end, Communists centered their activism on speeding the system’s ruin by exposing the problems capitalism created, helping workers understand class conflict, fighting for racial justice, and exposing liberals and other non-Communist leftists as “social fascist” betrayers to the workers’ cause.

This article presents maps and data that could not be displayed in the book Red Chicago. Maps show party offices and places used in demonstrations and mass meetings. Accompanying this is a timeline of more than 300 demonstrations, mass meetings, organizing campaigns, recreational events, and other actions staged by the Party and its auxilliaries from 1929-1934.

Randi Storch is Professor of History at SUNY Cortland and author of Red Chicago: American Communism at its Grassroots, 1928-35 (University of Illinois Press, 2007)

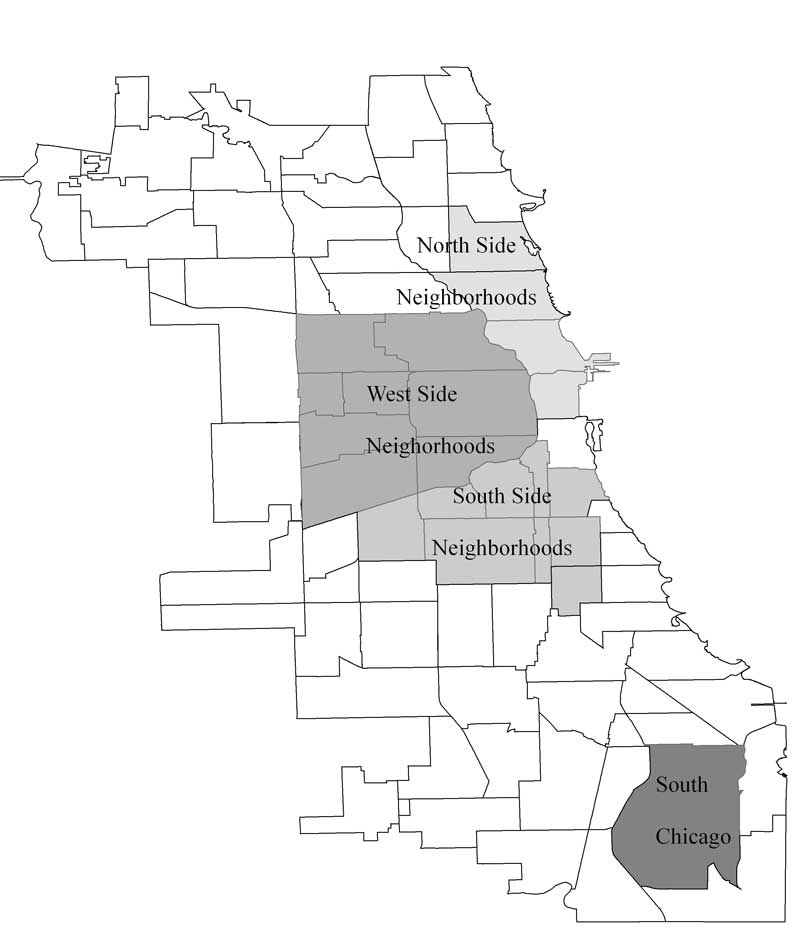

From 1919 through the mid 1920s, Communist Party membership was confined to a small number of ethnic and labor enclaves where neighborhood ties and radical political traditions sustained the movement. Between 1928 and 1935, however, Chicago’s Communist Party increasingly appealed to a broader group among the city’s African Americans, ethnics, students, artists, writers, workers (men and women alike) as party members developed campaigns that addressed the real-life problems facing these groups. Chicago’s Communists were most successful in the densest industrial areas and working-class neighborhoods in Chicago’s West Side, the Black Belt, Packing Town, the North Side, Cicero and South Chicago where the Depression’s effects hit with devastating force.

Because the city was the second largest industrial area in the nation during the interwar years, communists believed that Chicago would be a vital city to spread their message, recruit members and organize a movement. In 1930, thirty-eight railroads and twenty-three trunk lines terminated there, contributing to the city’s distinction as the world’s leader in the production and distribution of food staples; and in the manufacture and distribution of meat, meat products, agricultural implements, dry goods, railroad supplies and foundry products.

The union stockyards, steel plants, railroad yards, garment factories and farm equipment industries gave Chicago its working-class

cast. Chicago was also one of the most heavily unionized cities in the country, yet these mass-production workers had been unable to build lasting unions, a

problem Communists hoped to fix. The Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL) held together an assortment of mostly craft workers. In the aftermath of failed industrial organizing campaigns in meatpacking and steel, and almost a decade of employer-led open-shop drives, its member unions were not enthusiastic to build industrial unions. Communists believed the time had come for the city’s mass production workers – first and second generation Eastern-European immigrants, black migrants, and Mexicans and Mexican-Americans—to create interracial and multiethnic unions. Using direct and confrontational tactics, Communists promoted welfare, civil rights, inclusive and militant unions and anti-imperialism.

Chicago’s Communists were heir to the city’s radical traditions. The city was the site of the 1886 Haymarket tragedy, the eight-hour movement, and the 1894 Pullman Boycott, as well as the birthplace of the Industrial Workers of the World and the American Communist party. Stretching their reach into distinct neighborhoods, Communists set up, used and/or co-opted ethnic clubhouses, restaurants, newspapers, and theaters in order to get their message out. By the mid 1930s, Chicago Communists were deeply rooted in ethnic groups, traditions, workplaces, neighborhoods and causes. In this way Chicago’s Communists built on local, leftist cultures and developed their own enclaves that dotted city’s working-class neighborhoods. The maps within Red Chicago illustrate this development.

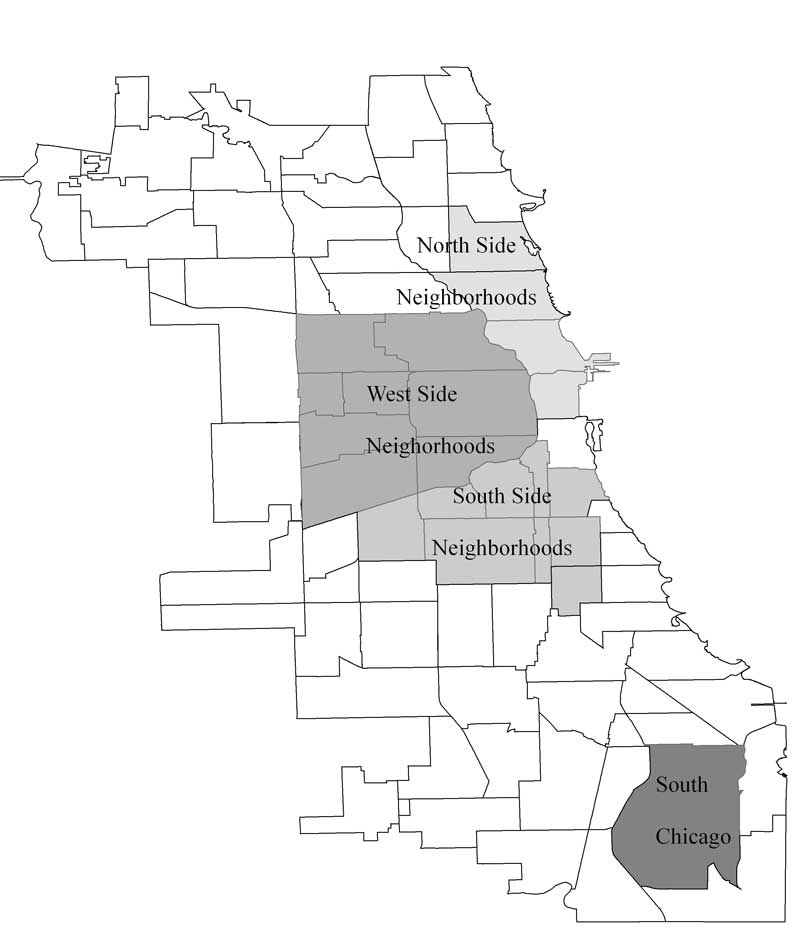

Neighborhoods of concentration (map by Lezlie Button)

(map by Lezlie Button)

The map titled “Neighborhoods of Concentration” highlights areas in the city where Chicago Communists centered their organizing activities in the years between 1928 and 1935.

The North Side neighborhoods ranked second or third in terms of membership numbers (running between 240 and 250), and usually rated first in the amount of dues paid because of the number who were well-paid, skilled workers. Varying levels of wealth and employment help explain the mixed response to the party in the North Side, which included the most economically diverse neighborhoods in the city, encompassing affluent blocks as well as the tenements in “Little Hell.” Extending northward, this section included Lincoln Park, which was wealthier than the Lower North Side and had only 18.65 percent of its residents on relief, compared to 26.08 percent on the Near North Side. Lincoln Park housed Germans, Yugoslavs, Hungarians, Rumanians, Irish, Italians, Poles, Russians, English and Swedes. Above Lincoln Park was Lake View, a mostly German enclave where Scandinavians played a particularly important role in the building trades, which were hit hard by the Depression.

The map at right depicts the locations on the north side of Chicago where the party set up communist Party schools, held meetings and events, and organized workers. Communists’ North Side labor organizing focused on the Stewart Warner plant, on the neighborhood’s Deering plant, its Hart, Schaffner and Marx factory, and among building-trades workers at various sites. Activists planned demonstrations at Washington Square Park, known as Bughouse Square, a free speech park on North Clark where bohemians, radicals, and any interested passerby had an open invitation to get up on a soapbox and riff. Communists also held meetings in the Sons of Israel Hall and in Viking Temple (3257 Sheffield Ave) and Imperial Hall (1710 Cornelia Ave) and participated in the numerous ethnic social organizations of the Scandinavians and Ukrainians living in the area. A few were even known to pass time at the Dil Pickle. On the North Side, the party published Radnik and the Armour Young Worker. In the areas of the section closest to the Loop, members organized meetings for the John Reed Club, the Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born, the American Youth Congress, the National Counter-Olympic Organizational Committee and the American League Against War and Fascism.

West Side membership also ran between 240 and 250 and can be understood by recognizing the varying levels of poverty there. During the Depression, jobs were hard to come by and destitution was widespread. West Town housed unskilled laborers, a majority of whom were Poles, Italians, Jews and Norwegians. In 1934, 22.88 percent of the families in this neighborhood were on relief. Near West Side workers of Italian, Russian, Greek, Polish and German descent lived in multifamily units. This neighborhood included a large Jewish population that supported eleven synagogues. Hit hard by the Depression, 43.74 percent in the Near West Side were on relief in 1934. A less run-down and poor area, the Lower West Side was composed mostly of Czechs and Yugoslavs, Poles, Lithuanians, Italians, and some Germans. Only 18.54 percent of the Lower West Side’s residents collected relief in 1934, but the residential area was congested.

This map depicts the locations on the west side of Chicago where the party set up communist Party schools, held regular meetings, organized mass rallies and mobilized workers. In West Town the party relied upon community institutions as the settings for their meetings, such as the Labor Lyceum Hall, the Ukrainian People’s Auditorium, the Slovak Workers’ Society, and the Hungarian Workers’ Society. Relying on the fact that this neighborhood was home to the largest Polish community in the city, party organizers called meetings of the Polish antifascist committee in this neighborhood. They also drew heavily on the large Jewish community and organized gatherings at the Jewish Club. Communists successfully recruited residents through their Unemployed Council protests at Humboldt Park relief station and at their Unemployed Council meetings at the Folkets Hus, a cultural meeting hall in the area owned by non-party, sympathetic residents. They also had some success mobilizing public school and junior college students to protest war. Several party newspaper offices, Party leaders’ offices and trade union and unemployed council meeting sites pepper West Side neighborhoods and demonstrate the significance of the region and the diversity of activities that occurred there.

The greatest number of recruits in this period came from the section on Chicago’s South Side that embraced the Black Belt and Packingtown. In 1931, this section recorded 342 members. The party was successful in these areas because they were two of the poorest and most segregated communities in Chicago. The Black Belt had some of the most unhealthy conditions. Located three miles from many of their co-workers in the Back of the Yards, blacks, who made up 30 percent of the packinghouse workers in 1930, lived in a world separate from white Back of the Yards. By 1930, 90 percent of all Chicago’s blacks lived in census tracts where more than 50 percent of the inhabitants were black. The core of Black Belt residents, living between State and Wentworth, lived in run down and overcrowded apartments and kitchenettes and paid exorbitant rents. Residents of surrounding neighborhoods violently enforced segregation. With separate and unequal facilities, blacks struggled to maintain their own segregated schools, hospitals, recreation facilities, movie theaters, restaurants, and taverns.

The Back of the Yards also had poor housing and environmental conditions but here, white ethnics and Mexicans peopled the dilapidated area. As part of an industrial belt that ran through the city’s southern edge, the Back of the Yards offered residents poor living conditions. The pungent odor of the stockyards, pollution and congested housing led to high rates of infant death and tuberculosis. Unskilled Slavs and Mexicans lived in decaying and bug-infested two-story wood homes where loud noises and the stench-filled air continually reminded them of their proximity to cattle arriving daily for slaughter. Only skilled and semiskilled Slavic workers could afford to live in brick or better wood-constructed homes south of Forty-Seventh Street, just below the neighborhood’s worst area.

South Chicago was home to the city’s steel mills and its workers and was the most difficult region of the city for party members to make inroads. Neighborhoods grew up around ethnic national churches and steel employers and were rife with ethnic conflict. Communists worked diligently to overcome these divisions and to organize steel workers into militant unions. They established party schools to educate neighborhood residents about capitalism and socialism, held open air meetings, and talked over lunch with co-workers. In the end, this region of the city would be the least amenable to the party’s message.

Here are the the locations on the south side where the party set up communist Party schools, held meetings and events, and organized workers. It shows how the party worked within established parks, workplaces and ethnic organizations and also established its own. Party work centered on organizing employed workers and extended into unemployed organizing, campaigns for racial equality and Marxist education. Black Belt shop work included Ben Sopkins and Sons clothing factories, the community’s Capitol Dairy plant, and local laundries, whereas Packingtown activity centered on the stockyards and as only secondarily channeled into the Crane Company, just west of the Back of the Yards. Communists pushed for interracial activity in both communities. They advocated that whites travel into black neighborhoods in the South Side and march with blacks during hunger marches, funeral processions and Labor Day demonstrations. They also embraced local community institutions by calling their meetings in the Odd Fellows, Pythian, Royal Circle and Forum halls and Lithuanian Auditorium and holding their public protests at local parks, such as Washington Park and Ellis Park, where traditions of open-air political discussion and debate ran deep. For those stimulated by Communist speeches and activism, a Workers’ Book Store on Indiana and Forty-third, at the heart of the black community, provided supporting literature.

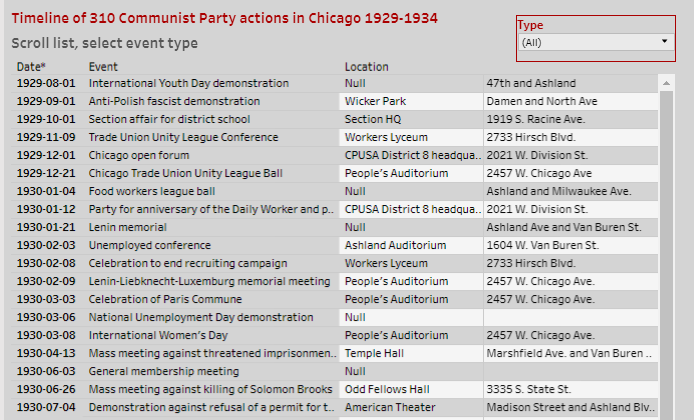

Now examine the timeline of more than 300 Communist Party marches, demonstrations, mass meetings, picnics, dances, organizational meetings, and other actions that kept party members and supporters busy from 1929 through 1934. Sort by event type.

Click to see timeline

Click image to the right to see the the full interactive timeline of Communist Party actions in Chicago 1928-1933

(map by Lezlie Button)

(map by Lezlie Button)