by Katie Anastas

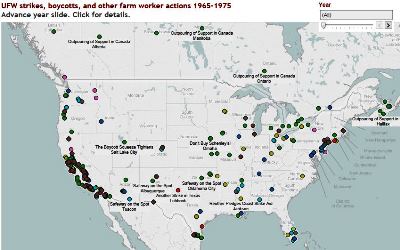

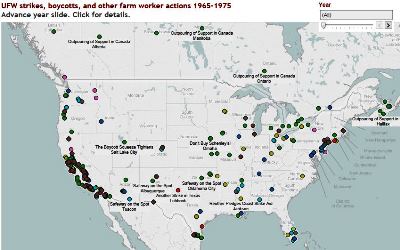

UFW strikes, boycotts, and other actions 1965-1975. Click to see map and charts

In 1965, Filipino farm workers in the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, led by Larry Itliong, began a series of strikes in Delano, California, demanding a minimum hourly wage of $1.40. Mexican-American farm workers in the National Farm Workers Association, led by Cesar Chavez, also joined the strike. By March 1965, Chavez was meeting with leaders of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) in Chicago, discussing plans to organize agricultural workers across the country. The NFWA and the AWOC merged into one union, the United Farm Workers Association (UFW), in 1966, beginning a movement that would garner support from politicians, civil rights groups, students, and religious leaders worldwide.

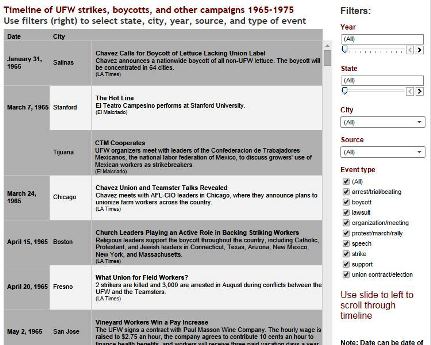

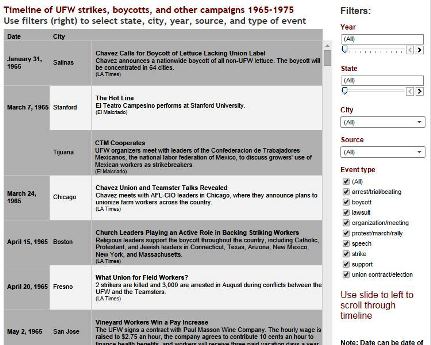

Click to see interactive timeline of UFW strikes, boycotts, and other actions 1965-1975

The UFW faced two main threats to the success of the strikes. One was a rival farm worker union affiliated with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, which competed with the UFW for contracts with growers. The UFW would continue to have a strained relationship with the Teamsters union throughout the next decade. A second threat was the use of strikebreakers,often illegal immigrants from Mexico, who worked for low wages at struck farms. In time, the UFW would win the support of many former strikebreakers and also former teamsters.

Throughout 1965, thousands of California farm workers went on strike and demanded union representation elections. Many were arrested by police and injured by growers while picketing at fields. On September 8, 1965, the grape strike officially began in Delano. Support quickly spread throughout California in the following months, with union supporters holding rallies in several cities and marching from Delano to Sacramento. In December, union representatives traveled from California to New York, Washington, D.C., Pittsburg, Detroit, and other large cities to encourage a boycott of grapes grown at ranches without UFW contracts. El Teatro Campesino, founded by Luis Valdez, began performing songs, poems, and plays to raise awareness of the strike and other experiences of Mexican-Americans. Important too was the union newspaper, El Malcriado, that had begun publishing in late 1964, first in Spanish, later in bilingual editions.

In the summer of 1966, the AWOC and the NFWA merged into one union and proceeded to win a representation election at the DiGiorgio Corporation. The newly formed UFW continued to encourage the grape boycott, receiving support from church groups, universities, and other unions throughout California. In the Northwest, unions and religious groups from Seattle and Portland endorsed the boycott. Farm workers in Arizona also went on strike and demanded UFW contracts. UFW supporters were arrested throughout the country, often for violating court injunctions specifying the number of pickets allowed at each location, or for trespassing onto farms to speak with strikebreaking workers. Supporters formed a boycott committee in Vancouver, prompting an outpouring of support from Canadians that would continue throughout the following years.

In 1967, the UFW opened hiring halls in Delano, Coachella, and Lamont, and El Teatro Campesino performed throughout the country. UFW supporters in Oregon began picketing stores in Eugene, Salem, and Portland. After melon workers went on strike in Texas, growers held the first union representation elections in the region, and the UFW became the first union to ever sign a contract with a grower in Texas.

National support for the UFW continued to grow in 1968. Hundreds of UFW members and supporters were arrested throughout the year, both by California police and by Texas Rangers. Picketing continued throughout the country, including in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Florida. The mayors of New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Buffalo, Detroit, and other cities pledged their support, and many of them altered their cities’ grape purchases to support the boycott. California grape growers sued the UFW and five other unions for $25 million because of the New York boycott of grapes. This was the first time growers admitted that the boycott was having a significant economic impact.

In 1969, support for farm workers’ organization efforts increased throughout North America. The grape boycott spread into the South as civil rights groups pressured grocery stores in Atlanta, Miami, New Orleans, Nashville, and Louisville to remove non-union grapes. Student groups in New York protested the Department of Defense and accused them of deliberately purchasing boycotted grapes, refusing to enforce immigration laws, and therefore interfering with the success of the UFW. On May 10, UFW supporters picketed Safeway stores throughout the U.S. and Canada in celebration of International Grape Boycott Day. Civil rights leaders like Reverend Ralph Abernathy and political leaders like Senator Edward M. Kennedy continued to show their support at rallies and demonstrations. Cesar Chavez also went on a speaking tour along the East Coast to ask for support from labor groups, religious groups, and universities.

In 1970, 26 grape growers in the Delano area signed contracts with the UFW. This was a major victory for the union, since these growers produced 50 percent of the table grape crop. The UFW expanded beyond the Central California region and began organizing farm workers in Northern California, beginning with Sutter and Yuba Counties. The UFW opened offices throughout California and Arizona, and boycott committees were founded in Oklahoma. After 10,000 lettuce workers went on strike within a week, Chavez announced a boycott of all non-union lettuce, which received national support. Safeway stores became principal targets of the lettuce boycott, and they refused to remove non-UFW lettuce despite demonstrations at stores throughout the U.S. and Canada.

In 1971, the UFW began demonstrating against the U.S. Department of Defense at military bases throughout the country to continue protesting the purchase of boycotted lettuce by the military. Members of other unions and religious leaders also attended these protests. The UFW also filed a lawsuit against the Department of Defense and accusing the government of reducing purchases from growers with UFW contracts while increasing purchases from non-union farms. In April, the UFW signed a contract with Mel Finerman Co. covering over 5,000 workers. The company produced lettuce in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado and was the largest independent lettuce producer in the U.S. The UFW also announced a complete boycott of all Safeway stores in the country.

In 1972, Cesar Chavez participated in one of his most famous fasts, going without food for 24 days in protest of an Arizona law prohibiting secondary boycotts and strikes during harvest time. Workers at several California farms went on strike after the growers refused to renew their contracts with the UFW. These strikes resulted in hundreds of arrests. In March, the UFW won an election to represent 1,200 orange pickers at Minute Maid in Miami, becoming the first union to organize migrant workers in Florida.

In 1973, 170 growers who were prepared to sign contracts with the UFW unexpectedly renegotiated their contracts with the Teamsters, affecting over 30,000 workers. In response, the UFW called for new union representation elections at these ranches and a boycott of all grapes grown at farms with Teamsters contracts. Hundreds of members of both unions were arrested as confrontations between the two groups became more violent. After the owners of the Gallo Brothers vineyards signed contracts with the Teamsters, the UFW called for a nationwide boycott of all Gallo products. Over 3,000 UFW members were arrested in August, prompting the Justice Department to ask the FBI to investigate accusations of police brutality.

The UFW continued to receive more support in 1974. Major labor groups, civil rights groups, and religious groups in New Jersey announced their support, and several other AFL-CIO unions agreed to boycott all Safeway stores. Groups like the American Federation for Television and Radio Artists and the Los Angeles County Labor Federation produced free advertising campaigns to encourage the public to participate in the boycott. Stores in Canada, California, Illinois, Ohio, New York, Louisiana, and other states agreed to remove non-UFW grapes and lettuce from their shelves. In autumn, Cesar Chavez attended labor conferences in Europe, where labor leaders from Britain, France, Italy, Germany, and Scandinavia expressed their willingness to help bring the boycott of non-UFW grapes and lettuce to Europe.

In 1975, Governor Jerry Brown of California proposed a new labor bill that would allow for secret ballot elections for farm workers to determine which union, if any, they wanted to represent them. This bill received support from both the UFW and the Teamsters, and thousands of people attended rallies and marches in Sacramento to express their support. The law was passed in June and went into effect in August. Following the passing of the bill, Cesar Chavez began a 1,000-mile march from the Mexican border to Sacramento. Along the way, he educated farm workers about the new labor law and encouraged them to vote for the UFW in upcoming representation elections. By mid-September, the UFW won the right to represent 4,500 workers at 24 farms, while the Teamsters won the right to represent 4,000 workers at 14 farms. The UFW won the majority of the elections in which it participated.

The Teamsters signed an agreement with the UFW in 1977, promising to end its efforts to represent farm workers. The boycott of grapes, lettuce, and Gallo products officially ended in 1978 as the UFW continued to sign contracts with growers.

The UFW was not the only organization working with farm workers during the decade between 1965-1975. In 1967, African American sugar cane workers in the South began demanding higher wages and advocating for better working conditions, and sharecroppers in Mississippi also began organizing. In Florida, church and labor groups joined together to form the Coordinating Committee for Farm Workers. Farm workers in Wautoma, Wisconsin, held rallies and marches in support of wage increases. In 1968, the Western Washington Huelga Committee began organizing hop workers in the Yakima Valley, and pineapple workers in Hawaii earned the right to a $2.49 minimum hourly wage after 61 days of striking. In 1969, melon workers in Texas went on strike and demanded higher wages. In 1971, Puerto Rican farm workers began forming a union and protesting the use of harmful pesticides. The Eastern Farm Workers Association, formed in 1971 by nursery and greenhouse workers, became the first union to organize farm workers on Long Island and supported a strike by migrant farm seeking a minimum hourly wage of $2.89. Onion workers in northwestern Ohio formed the Farm Labor Organizing Committee in 1972. Inspired by the success of the UFW, farm workers formed groups like the Asociacion de Trabajadores Agricolas in New Jersey, and Obreros Unidos in Wisconsin.