by Eleanor Mahoney

In Washington State, the Federal Art Project supported artists in a wide variety of endeavors. This May 30, 1937 article from the Seattle Daily Times highlights the creation of murals, sculpture, dioramas and model ships. In August 1935, the Federal Government launched its most ambitious New Deal visual arts initiative, the Federal Art Project (FAP). Aimed at conserving “the talent and skills of artists who, through no fault of their own, found themselves on the relief rolls and without means to continue their work,” the FAP ultimately employed more than 5,000 men and women over an eight-year span (1935-1943).

[1] In addition to aiding the unemployed, the program also sought, according to an early program manual, to make art accessible to the population at-large, “to integrate the fine with the practical arts and, more especially, the arts in general with the daily life of the community.”

[2] As FAP Director Holger Cahill explained, “The resources for art in America depend upon the creative experience stored up in its art traditions, upon the knowledge and talent of its living artists and the opportunities provided for them, but most of all upon opportunities provided for the people as a whole to participate in the experience of art.”

[3]

The FAP was one of a series of cultural initiatives launched by the Roosevelt administration during the summer of 1935. Housed within the Works Progress Administration (WPA), these creative programs were collectively known as Federal One (short for Federal Project Number One) and included the Federal Theatre Project, the Federal Writers Project, the Federal Music Project, the Historical Records Survey (originally part of the Writers Project) and the FAP. Together, they represented a key element of President Roosevelt’s “Second New Deal,” a period (1935-1938) that also witnessed the implementation of such landmark programs as Social Security and the National Labor Relations Act.

Each of the Federal One projects had its own director and administrative structure. Holger Cahill, for example, directed the FAP from its earliest days in 1935 until the program’s end in 1943.[4] However, all the initiatives fell under the broader auspices of the WPA and were thus subject to the funding difficulties that plagued the agency as a whole. Particularly challenging in this regard was the absence of program legislation. Created by Executive Order, the WPA lacked statutory authorization for funding and was thus subject to the annual Congressional appropriations process – a situation that not only left it exposed to political wrangling, but also hampered efforts at long term planning and year-to-year organizational consistency at the state and national levels. [5]

The primary purpose of the FAP was to provide employment to artists on relief.[6] In the mid 1930’s, over 50% of American artists were eligible for public assistance according to estimates by Project officials.[7] “No one became rich or famous directly through this program,” Northwest art historian Martha Kingsbury has written, “…but artists in areas like the Northwest received two very valuable benefits: the recognition and status of having a respected profession and the encouragement that implicitly went with that; and, more practically, the time and materials made available by the paycheck, which enabled them to persist in their art.” [8]

After a boom during the 1920’s, the art market collapsed in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash, with sales of both imported and American artwork decreasing some 80% over the next four years. Employment opportunities also fell significantly, with the number of artists and teachers of art declining by 9.2% in the 1930’s, even while the population as a whole increased by 7.2%.

[9] As Harry Hopkins, Director of the WPA succinctly put it when discussing the artist’s plight, “Hell! They’ve got to eat just like other people.”

[10] Even men and women who achieved a degree of renown later in life, including Pacific Northwest artists like Mark Tobey and Morris Graves, participated in the FAP, a testament to the weakness of any private market for art during the Depression.

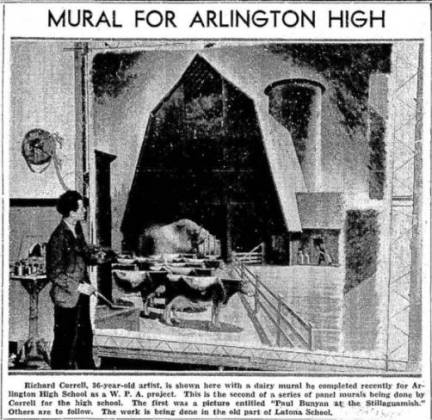

Artist Richard Correll works on a Federal Art Project sponsored mural at Arlington High School. He also painted a Paul Bunyan-themed piece for the same site, among multiple FAP works he completed. Image Seattle Daily Times, December 8, 1940.

Artists supported by the FAP were active in a wide variety of areas, including traditional pursuits, like easel painting, as well as more novel (for the era) fields like community education and the documentation of folk art. Over the course of 8 years, FAP artists produced some 108,000 paintings, 17,700 sculptures, 11,200 print designs, 35,000 poster designs and 2,500 murals.[11] In addition, more than 100 Community Art Centers opened their doors across the nation, including one very successful site in Spokane, Washington. These institutions, among the first to teach painting, sculpture and design outside the setting of a college or university, exposed millions of Americans to the theory and practice of art. The FAP also was responsible for creating the Index of American Design, a massive program of research, which sought to document the breadth of the nation’s material culture, cataloging over 22,000 items and producing a series of guides outlining the techniques used in the creation of various traditional arts and crafts.[12]

On September, 29, 1938, the Spokesman-Review ran a story on the soon to be opened Spokane Art Center. It highlighted the community's contribution to the project as well as the caliber of work, which would soon be on display for citizens to view free of charge. In the image above, Washington State Federal Art Project Director R. Bruce Inverarity (at left) and Spokane Art Center Director Carl Morris mount a painting by Warren Weelock, an artist from New York. Among the most successful FAP-organized centers in the country, the Spokane Art Center welcomes thousands of local residents through it doors during its brief few years of existence.

In general, the FAP allowed more flexibility in subject matter and style than the Treasury Department’s Section of Painting and Sculpture, a program best known for sponsoring thousands of murals in post offices and courthouses. While similar themes, including regionalism, history, labor and folklore, dominated in both initiatives, FAP administrators did not require as strict an adherence to the precepts of the “American Scene” movement as their counterparts in the Section. For example, Seattle artist Fay Chong, who participated in the FAP for a number of years remembered that, “…fortunately I was very free to do what I wanted to do as far as subject matter; I had my choice, which was very good, and the same way with my printmaking. I think I had a choice there, too, but there was of course a time requirement that we had to produce so many prints or so many paintings in a certain time, you see, but I suppose that is a necessity for a project or for any kind of organization.”[13]

Another significant difference lay in the structure of each program. Centrally managed in Washington, D.C., the Section had little to no official footprint in individual states. In contrast, the FAP, a much larger program in terms of employment, developed regional and state bureaucracies, both of which exercised a fair amount of control over project selection, artist recruitment and program direction.

This de-centralization, while perhaps allowing for more flexibility, also led to conflicts with local officials, especially those within the existing WPA state structure, who resented the intrusion of Washington D.C. appointed administrators onto their terrain. Such was the case in Washington, which was among the last states in the country to set up an Art Project due to internal bickering among various WPA managers.[14] The situation was so toxic, in fact, that many artists, fearing no program would ever take shape, deliberately misrepresented their skills on relief applications, in the hopes of gaining employment faster in another field, even working as laborers to make ends meet.[15]

For almost a year, government officials in Washington argued over the FAP’s value, cost, and even the suspected presence of radical elements among eligible artists. Then WPA State Administrator George Gannon did not support the project, believing it to be a worthless investment, given the fact that, in his words, “there are only 20 artists in the whole state and eighteen of them cannot turn out a class of work that would justify employing them as artists.”[16] Conditions eventually deteriorated to such an extent that in December 1935, Burt Baker Brown, Director of the Art Project in the Western Region, asked to be relieved of any responsibility for Washington.[17] National leaders, including Holger Cahill, did not give up, however, and change arrived with the appointment of a new State Administrator, Don Abel, in early 1936.[18]

Progress came quickly following the transition in leadership and by June 1936, a State FAP Director, Robert Bruce Inverarity, had been appointed and a small Art Program established.[19] “Hungry artists from the state of Washington are to be taken from the class of forgotten men and given works projects,” a June 24, 1936, article in the Spokane Chronicle reported. “Painters, sculptors, poster artists, lithographers, stone cutters, wood carvers, weavers, plaster casters, and craftsmen in metals and other materials,” were all encouraged to apply for employment through the FAP.[20]

Within a few months of assuming the directorship, Inverarity succeeded in filing the quota of 25 artists.[21] Through hard work and outreach, he also managed to secure a number of project co-sponsors, including the University of Washington, Cushman Indian Hospital in Tacoma, the Woodland Park Zoo and Seattle City Light. In July 1936, the Everett Evening News reported on a promotional visit by Inverarity to the city. Describing the FAP as “an unusual opportunity for Everett’s tax-supported institutions to be decorated throughout at a trifling cost,” the paper also highlighted the potential educational value of public art. “An especially valuable phase of the undertaking,” the article noted, “will be the opportunity for kindergartens to obtain wall paintings of nursery scenes and verses.”[22] According to the FAP manual, Inverarity was to solicit potential partners from all public and quasi-public agencies in the state to see if any sites wanted or needed art.[23] “I would talk to Rotary Clubs, girl scouts, church groups, anyone…,” he remembered.[24] In addition to being tax-supported, the organizations were required to contribute the majority of non-salary project costs. In return, a site received the resulting artwork on indefinite loan.[25]

Among the most visible projects completed by FAP artists in Washington State were roughly a dozen murals. These included: “The Theatre of the East,” “The Theatre of the West,” and “The Theatre in the Time of Shakespeare” by Glenn Sheckels for the University of Washington Drama Department; a decorative mural for the small animal house at the Woodland Park Zoo; maps of eastern and western Washington for the newly constructed Public Lands and Social Securities building in Olympia; and "Landing of the Seattle Pioneers," "Pioneer Life at Alki," and "Logging on Elliot Bay" by Jacob Elshin for West Seattle High School. Like the more famous post office murals associated with the Section, these paintings were often visually and thematically striking, capturing local folklore and history in a dramatic figurative style. In addition, the FAP stressed the educational aspect of these paintings and encouraged artists to work in public and on-site so that Americans might better understand the theory and practice of art as well as simply enjoy the final product. [26]

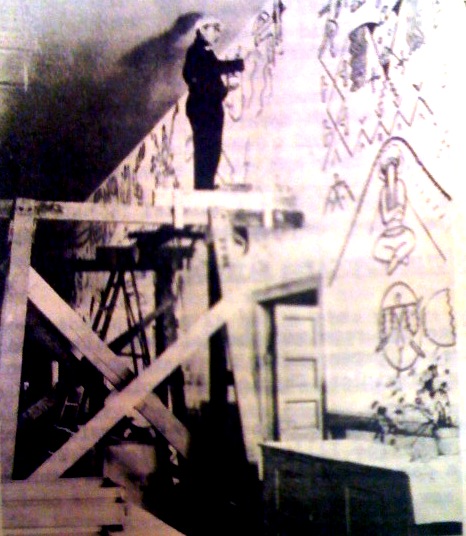

In this image, from the May 1939 edition of Indians at Work, a publication of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Uinta Ute artist Julius Twohy stands on scaffolding while painting a mural at Cushman Indian Hospital in Tacoma. Twohy was the only Native artist to participate in the Federal Art Project in Washington State. One particular mural, "The Flight of the Thunderbird," garnered significant attention, including a story in the Los Angeles Times and over a dozen mentions in various Washington media outlets. Created for the Cushman Indian Hospital (a federal facility located on Puyallup Tribal land in Tacoma) by Uinta Ute artist Julius Twohy, the impressive 72-foot painting presented the story of the Thunderbird from the perspective of various indigenous peoples. Traveling from west to east (left to right) across the wall, Twohy's Thunderbird moves through different regions and cultures, shifting appearance and meaning for each group it encounters. On the far left is a figure that evokes the Northwest Coast, a Thunderbird that might appear on a Totem from British Columbia, followed by symbols and imagery often associated with the Great Basin, Southwest (a loom), Plains (tipi and horses) and Great Lakes (water and canoes). In each locale, according to an interview with the artist, the Thunderbird appears to chiefs and medicine men (also depicted in the mural) providing instruction and spiritual guidance.[27]

In addition to murals, FAP artists also worked on a variety of other projects. One that received particular attention was a model of Diablo Dam on the Skagit River in North Central Washington. Built using the dam’s actual blueprints in a workshop in the Terminal Sales Building in Seattle, the model featured a “real concrete Diablo Dam, a mountainside and a riverbed, and running water, all in a space eight feet long and six feet wide.”[28] Also noteworthy were a series of sculptures for the Walker-Ames Room at the University of Washington, including a limestone bust of William Shakespeare by Seattle artist Irene McHugh, as well as a linoleum mosaic at Point Defiance (then called Tacoma Park) by Richard Correll, a politically engaged artist who also contributed to the Communist Party affiliated Voice of Action newspaper, the Washington New Dealer and the New Masses.[29]

A series of visits from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt represented a high point for the Federal Art Project and the WPA as a whole in Washington State. In an oral history interview recorded many years later, State administrator Don Abel remembered the events fondly, “I think that probably the most enthusiastic supporter of the Art Projects and other types of projects that were not work projects was Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt," he recalled. "She was out here a number of times because her daughter lived in Seattle, and she invariably went to the different Art Projects, and particularly projects where women were involved in the Seattle area. I don't recollect that she got over to Eastern Washington, but in the Seattle-Tacoma area, she spent considerable time visiting all of the Art Projects and the projects involving women.”[30]

During a 1937 visit to Washington State, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt examined the work of "an old ship captain" employed by the FAP as a maker of model ships. During her stop, Mrs. Roosevelt asked multiple questions regarding the project's activities and said she "hated to go" before leaving to address the city council and King County Commission. In 1939, the structure of the WPA (and by extension the Federal One programs ) changed dramatically. The newly created Federal Works Agency (FWA) assumed management of all WPA programs, thereby eliminating the agency's status as an independent entity. The Works Progress Administration soon became the Work Projects Administration, reflecting the FWA's heightened emphasis on results and accountability. With shifts in management came changes in support and funding. The Federal Theatre Project, long under attack by the right-wing, was eliminated, while the other Federal One programs suffered deep cuts in their Federal allocations. Control shifted to the states and, as a result, the Federal Art Project in Washington State became the Washington Art Project, with the University of Washington becoming the official sponsor, though the federal government still contributed a majority of funds. Work continued, though morale suffered in the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere as a result of the changes. In these later years, Inverarity, who remained Director until the Project's end in 1942, was able to initiate a few new programs, including an ambitious effort to open small art galleries and exhibition spaces across the state, so that residents of smaller towns and rural areas could enjoy exposure to art. A Seattle Daily Times article from September 7,1939 announcing the shift in management stressed that the program would continue its mission of "the fostering art talent and the teaching of art to the underprivileged."

Over the course of 8 years, the Federal Art Project aided thousands of needy artists and craftspeople, including dozens in Washington State. Like other Americans, artists were struggling to survive the Great Depression, searching for any kind of gainful employment amidst the greatest economic calamity the nation had ever known. As a result of the WPA's Federal One initiative, men and women engaged in creative work like design, painting, writing, theatre and music, were able to contribute their skills, knowledge and know-how to society during a critical moment of change and uncertainty. Whether it was painting classes in a community center, high quality murals in a local high school or the opening of a rural gallery, the Federal Art Project connected art and artists to the public in new and innovative ways. Like other New Deal programs, the Art Project often suffered from bureaucratic in-fighting and a lack formal administrative structure, but, despite these difficulties, it ultimately succeeded bringing art to the people and inspiring an enduring interest in the field among a generation of Americans.

Copyright (c) 2012, Eleanor Mahoney

[1] On May 6, 1935, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 7034, which created the Works Progress Administration. On August 2, 1935, Harry Hopkins, announced the creation of Federal Project Number One, which offered employment to relief eligible men and women in theatre, music, visual arts and writing. Text related to the purposes of the Federal Art Project come from a 1935 FAP manual, cited in Martin R. Kalfatovic, The New Deal Fine Arts Projects: A Bibliography, 1933-1992 (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1994), xxx.

[3] Holger Cahill, "American Resources in the Arts," in Art for the Millions: Essays from the 1930's by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project, edited by Francis V. O'Connor (Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society LTD, 1973), 43-44.

[4] Cahill served as Director for the program's entire duration. Born Kirstjan Bjarnarson in Iceland, he immigrated to the U.S. as a young child, growing up improverished in South Dakota. During his teenage years, Cahill dedided he wanted to be a writer and traveled to New Yok City to pursue his dream. He took night courses ast New York University and changed his name - to Holger Cahill. Before joining the FAP, Cahill worked for various New York publications and museums, including time spent as exhibitions director at the Museum of Modern Art.

[6] The FAP's mission differentiated it from another New Deal public art initiative, the Section of Painting and Sculpture (the Section). Managed by the Treasury Department, the Section did not take an artist’s financial need or employment status into account when awarding commissions and instead used the blind competition as its primary selection mechanism

[7] According to an Associated Press article published in the Seattle Daily Times on October 13, 1936, FAP Director Holger Cahill estimated that there were 12,000 artists in the U.S. in 1936, of which 58% were in need of relief. Cahill reported that if he had the funds, 2,500 additional artists could be brought onto the WPA relief program, in addition to the 4,500 currently employed. “Art becomes an industry; Sales Beginning to Climb,” Seattle Daily Times, October 13, 1936, p.35.

[8] Martha Kingsbury, Art of the Thirties; The Pacific Northwest ( Seattle: Published for the Henry Art Gallery by the University of Washington Press, 1972), 11.

[9] Judith G. Keyser, The New Deal Murals in Washington State: Communication and Popular Democracy, (M.A. Thesis, University of Washington, 1982), 21

[10] The men and women employed by the FAP did not become wealthy by any means and many struggled to survive on their modest salaries of no more than $100/month. Bruce Bustard, A New Deal for the Arts (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration in association with the University of Washington Press, 1997) 7; Kingsbury, 11.

[11] Bustard, 9; Keyser, 50.

[13] Oral history interview with Fay Chong, 1965 Feb. 14-20, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Accessed September 6, 2012.

[15] Robert Bruce Inverarity, “Letter to R.C. Jacobson, Acting Administrator for State of Washington Works Progress Administration,” April 27, 1936, Record Group 69, Records of the Works Progress Administration, Regional and State Correspondence - Washington State, microfilmed by the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C; Regional WPA Director Joseph Danysh expressed similar sentiments in a newstory publihsed in the Bremerton Journal, July 2, 1936, “Starving Artists to Now Enjoy Life.”

[16] Judith G. Keyser, 84-85.

[19] Born in Seattle in 1909, Inverarity was the son of prominent local booster, lawyer and theater manager Duncan Inverarity; a connection that aided him as he sought out project partners. A 1928 graduate of Garfield High School, Inverarity had already gained a degree of local notoriety by the time he was eighteen. Standing almost six and a half tall, with a mop of blond hair and a seemingly permanent pipe in his mouth, the young artist was certainly memorable. A profile piece in the December 4, 1928 edition of the Seattle Star, described him as “one of the most unusual people in Seattle, no matter how you look at him. He’s Seattle’s youngest recognized artist. He’s taking an active part in introducing ‘modern art’ to a city that knew him as a school boy…” Less than a decade removed from High School, Inverarity had already worked as an instructor at Cornish College, the School of Creative Art in Vancouver and the University of Washington before joining the Federal Art Project.

[20] “Will Put Washington Artists Back on Job,” Spokane Chronicle, June 24, 1936.

[22] “WPA Offering Artist Work on Buildings,” Everett Evening News, July 11, 1936.

[23] Federal Art Project, Works Progress Administration, Federal Art Project Manual (New York: 1935), 8.

[25] Federal Art Project. Art in Democracy: Sponsors, Friends and Members of the Federal Art Project, Works Progress Administration (New York: Federal Art Project, Works Progress Administration, 1938), 31

[26] I have not been able to locate a central listing of all FAP murals completed in the state. As a result, the figure of “roughly a dozen” is based on a review of newspaper stories, archival records and a variety of secondary sources.

[28] “Federal Art Project Makes Model of Skagit Dam Site,” Seattle Daily Times, May 30, 1937, 7.

[30] Oral history interview with Don G. Abel, 1965 June 10, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Accessed September 6, 2012.