by Eleanor Mahoney

Painted by artist and University of Washington professor Ambrose Patterson, this mural, "Local Pursuits" is situated in the post office in Mount Vernon, Washington. The painting's dominant theme is agriculture, an important industry in the Skagit County community. (Courtesy Photo courtesy: Jimmy S Emerson, DVM, see http://www.flickr.com/photos/auvet/ for more photos)For roughly six months in late 1933 and early 1934, the Federal Government sponsored a widespread and largely successful visual arts initiative, the

Public Works of Art Project (PWAP). However, funding for the program was limited, and on June 30, 1934, the PWAP ended, leaving thousands of artists without work and millions of Americans wondering whether the nation’s brief flirtation with public patronage would carry on into the near future. Ultimately, the government did continue to provide funds in support of the arts, though the precise methods and outcomes varied according to the goals of administrators in Washington, D.C. and of local leaders in cities and states across the country.

One of the programs that filled the void left by the PWAP was the Section of Painting and Sculpture (the Section), which operated from October 1934 through July 1943.[1] During those nine years, the Section sponsored over 1,100 murals and close to 300 sculptures.

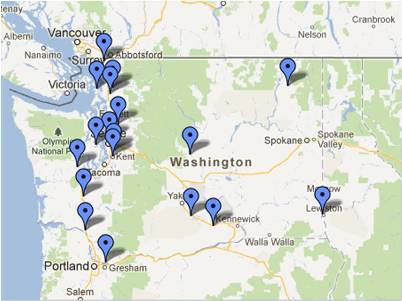

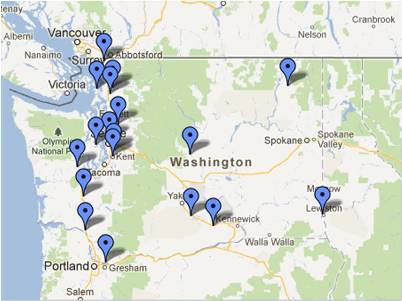

[2] In Washington, 18 post offices and many other public buildings received public art because of the program.

[3] From the Canadian border, to the Columbia River and the Idaho border, murals and carvings went up in cities, towns and rural hamlets. The Section sought to make art a part of everyday life in all corners of the nation by placing outstanding pieces in locations that citizens could visit frequently and at no cost. Here are many of the

post office murals in Washington State.

The location of post office murals in Washington State sponsored by the Section. View the post office locations along with mural images in a larger map.Like the PWAP, the Section

was managed by the Treasury Department. In addition, the same men, Director Edward Bruce, along with Edward Rowan and Forbes Watson, headed both the PWAP and the Section, providing continuity between the initiatives.

[4] Comprised largely of artists or those familiar with arts administration, the Section staff stood out in the generally staid Treasury building. As one Section administrator later remembered, “with the exception of Ned [Edward] Bruce we were all inexperienced in government procedures, but we did our best to conform to them. Treasury officials seemed to respect our efforts and were amused by the Section, which struck an eccentric, casual, free and easy note in the administrative machinery of procurement.”

[5]

Despite its similarities to the PWAP, the Section differed in key respects from the earlier effort. Most significantly, it was not a relief program; instead, officials used a blind competition to select artists with no consideration given to an individual’s income or employment status. Once chosen, an artist essentially became an independent operator, signing a contract to complete a specific project, rather than assuming a regular salaried position, as was the case with the Federal Art Project, a program of the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

[6] According to Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., the Section sought to secure “suitable art of the best quality” for public buildings.

[7] It aimed to do this in a rigorous and impartial fashion that allowed lesser-known artists, including a large number of women, to compete with more established painters and sculptors.

[8] In addition, whenever possible, the Section hoped its projects would stimulate the “development of art in this country,” through an emphasis on “cooperation” with local residents.

[9]

The vast majority of projects sponsored by the Section were intended for Federal buildings, largely post offices and courthouses as well as the vast new government complexes then being built in Washington D.C. Funding came from the Treasury Department, which, in theory, allocated one percent of a building’s total coast for decoration. In practice, the amount was usually less, but still enough to fund modest embellishments like smaller murals, sculptures and woodcarvings.

[10] On average, each mural cost roughly $1,300 with the sculptures falling a bit higher, about $1,900.

[11]

Commissioned for the post office in Sedro-Wooley, this mural, by native Washingtonian Alfred Runquist, depicts loggers and millworkers. (Courtesy Photo courtesy: Jimmy S Emerson, DVM, see http://www.flickr.com/photos/auvet/ for more photos)After initial site selection, Section administrators in Washington, D.C. appointed a local chairperson. He or she then chose a committee, comprised of prominent men and women affiliated with the arts, to send out competition announcements, receive and initially judge entries, and ultimately return a report, along with the submitted sketches, to the capital. For example, when the Section announced a mural competition for the Wenatchee (WA) Post Office in 1938, the committee included Dr. Richard Fuller, Director of the Seattle Art Museum, as chairperson; Carl Gould, a Seattle architect; Melvin Kohler, the Director of the Tacoma Art Association; and Ambrose Patterson, a Professor of Art at the University of Washington.

[12] Section officials in Washington, D.C. made the final decision on all projects, though national program administrators only occasionally overruled the choices of a local committee.

[13] The entire process from start to finish remained anonymous with names revealed only after selection, an important aspect of the Section’s mission and vision for artistic democracy.

[14]

Interestingly, in Washington State and in many other locations, a majority of artists received commissions for buildings that they had not actually applied to decorate. Instead, Section officials would assign new projects to artists whose sketches had been impressive, but not initially successful in earlier competition processes.

[15] According to one program administrator, “the fact that we awarded additional commissions as a result of sketches submitted in this competition made it clear to the artists that they were not wasting their efforts in a one-shot raffle. These awards helped to mitigate one of the greatest drawbacks to the competitive system.”

[16]

This practice did lead to political problems, however, as residents sometimes bristled when officials in Washington D.C. favored an outsider instead of a candidate from the region.

[17] For example, when Section officials chose Minneapolis artist Richard Haines to paint a mural for the new post office in Shelton, Washington, the local community openly complained about the selection. Haines tried to make the best of the situation and his logging-themed, egg tempura mural, “The Skid Road,” was actually the only one in the state completed on site. “Whenever possible,” he commented, “I feel painting of the murals on the spot should be encouraged. It is an enlightening experience both for the artist and the community.”

[18]

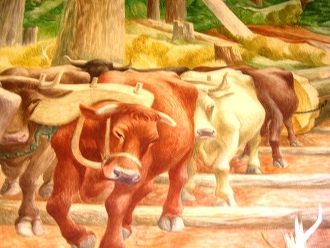

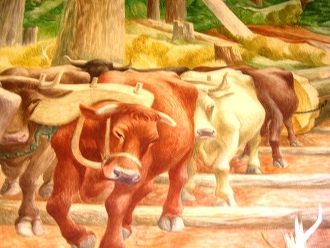

"Skid Road," depicts oxen being driven by a logger. it was painted for the post office in Shelton, Washington, a community with a long connection to the timber industry. (Courtesy Photo courtesy: Jimmy S Emerson, DVM, see http://www.flickr.com/photos/auvet/ for more photos)

Haines continued to have trouble, however, even after arriving in Shelton. He sought advice from the Shelton postmistress and local residents, but nonetheless faced continued censure. The postmistress sent him a rather scathing letter, which read, in part: “An ox is always shod. No one ever saw a driver on the off side of a team. The driver is at the back of the team, not the head. For myself, the faces of the drivers are awful. The loggers are not wicked, they are kindly, especially if allowed to drive…You have the faces too hard. They should be kindly—oxen are gentle, and so treated. Men such as you depict would not be allowed to touch a team.”

[19]

Such scrutiny was typical across the nation, as locals both took great pride in and turned a sharp eye on the murals going up in their midst. One scholar of the public art programs in Washington State commented that typically “people in the community were involved in talking about the murals, criticizing little details perhaps, but generally proud to have an art work in their town.”

[20] Edmund Fitzgerald, a Seattle artist, who painted a mural in the Colville, Washington, post office wrote to Section administrators in Washington, D.C. that, “the remarks of citizens made me feel proud and happy to think that I may have contributed in a small way to assist them in cultural consciousness.”

[21]

Art associated with the Section seldom contained explicit political messages. Even more than the PWAP, program administrators demanded adherence to the “American Scene,” a movement that stressed “regional and small town life and produced views of local color and straightforward celebrations of ideals such as community, democracy and hard work.”

[22] Common subjects in Washington State, for example, included the early 19

th century journey of Lewis and Clark, agricultural pursuits, fishing and the timber industry. In 1934, Director Bruce described the purpose of the Section as “to keep away from official art and to develop local cultural interests throughout the country.”

[23]

In addition to a lack of overt politics, Section officials also looked unfavorably on work that was too symbolic or abstract. They wanted the murals and sculptures to appeal to a broad audience, who would find the subjects both familiar and entertaining. In May 1940, Edward Rowan, a program leader in Washington D.C., corresponded on this topic with Douglas Nicholson, a California artist selected to paint a mural for the new post office in Camas, Washington. In response to seeing Nicholson’s sketches, Rowan wrote, “It will be appreciated if in the progress of the work you will continue to strive to make the work as interesting as possible for the citizens of Camas.”

[24]

Nicholson did strive to make his work appealing, traveling to the Camas region, along the north shore of the Columbia River just east of Vancouver, Washington, for inspiration and talking to a local historian before completing his work. Entitled “Beginning of the New World,” the mural is a somewhat futuristic rendering of Euro-American settlers and a Native woman and child as well as local industries of lumber, dairying, and fishing. It evidently did not please Rowan, who, in 1941, wrote in frustration to Nicholson that, “Frankly, I do not think the problem is well-solved…However, if you as the artist are entirely happy about this treatment this office will not require a change.”

[25]

"Beginning of a New World," by California artist Douglas Nicholson tells the story of Camas, Washington, in a style more impressionistic than many other New Deal murals. This contemporary photo also illustrates some of the spatial and aesthetic challenges faced by artists, who usually had limited space to work with in crafting their work. (Courtesy Photo courtesy: Jimmy S Emerson, DVM, see http://www.flickr.com/photos/auvet/ for more photos)As a result

of its broad geographic reach, the Section played an important role in shaping the public’s vision of the New Deal in Washington State. While the Federal Art Project concentrated its efforts and its personnel in Seattle, Tacoma and Spokane, the Section sponsored projects in smaller, rural communities. For many residents, the post office mural became the dominant image of New Deal visual art. Characterized by images of local industry, history and folklore, these American Scene-inspired works valorized local history, folklore and industry, presenting a relatabe, if at-times romanticized, view of life in the United States. For both residents and artists alike, the production and visibility of freely accessible public art became a point of pride, even if interpretive and aesthetic disputes did surface. As Ernest Norling, a Seattle artist who completed Section-sponsored murals in Prosser and Bremerton recalled, “It was - we were all very excited over the thing because it was a big thing for us. It was post office murals and the government was backing it so we all tried to do our best.”[26]

Copyright (c) 2012, Eleanor Mahoney

[1] In 1938, the Section of Painting and Sculpture was renamed the Section of Fine Arts. Though it lasted until 1943, work fell off considerably following the entry of the United States into World War II.

[2] Judith G. Keyser, The New Deal Murals in Washington State: Communication and Popular Democracy, Thesis (M.A.)--University of Washington, 1982), 66; Olin Dows, "The New Deal's Treasury Art Program: A Memoir," in The New Deal Art Projects: An Anthology of Memoirs, edited by Francis V. O'Connor (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972), 20.

[3] Marlene Park and Gerald E. Markowitz, Democratic Vistas: Post Offices and Public Art in the New Deal (Philadelphia:Temple University Press, 1984), 231-232;

[4] Bruce served as Director, Rowan as Assistant Director and Watson as Technical Advisor. “Bruce formulated general policy and ran interference with Roosevelt and Morgenthau; Watson continued to be an important art critic and publicized the Section’s work in countless newspaper and magazine articles; and Rowan made the day-to-day artistic and administrative decisions." Park and Markowitz, 7.

[6] Park and Markowitz, 8.

[7] Virginia M. Mecklenburg, The Public As Patron: A History of the Treasury Department Mural Program : Illustrated with Paintings from the Collection of the University of Maryland Art Gallery (College Park: University of Maryland, Dept. of Art, 1979), 12.

[8] Over 1/6 of the artists who worked for the section were women. Native American artists, especially in the western state and in Washington, D.C., also received many commissions. Only 3 African Ameican artists received commissions, however. Park and Markowitz, 8.

[12] Seattle Daily Times; December 23, 1938, 9.

[15] . Keyser, The New Deal Murals in Washington State, 69; In total, the Section held 190 competitions, from which roughly 600 participating artists ultimately received commissions. In 1940, Director Bruce noted that 572 artists had received commissions, 184 were winners of competitions, 382 were awarded work based on sketches. Park and Markowitz, Democratic Vistas, 12-13

[17] Park and Markowitz, 10-28.

[22] Bruce Bustard, A New Deal for the Arts (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration in association with the University of Washington Press, 1997), 24.

[23] Park and Markowitz, 8.

[26] Oral history interview with Ernest Ralph Norling, 1964 Oct. 30, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, accessed August 19, 2012, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-ernest-ralph-norling-13113.

<