by Magic Demirel

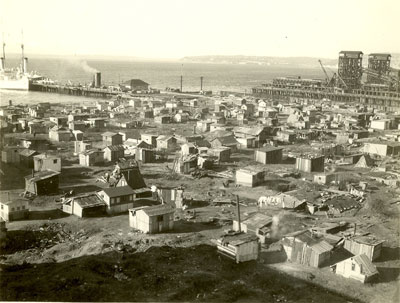

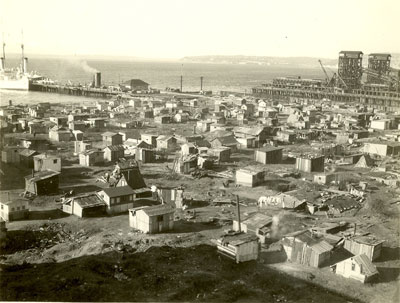

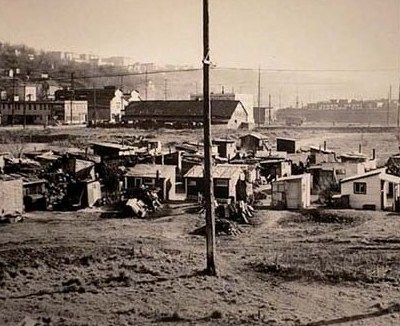

Seattle's largest Hooverville occupied nine acres that are now used to unload container ships west of Qwest Field and the Alaska Viaduct. (Courtesy King County Archives).The failure of Depression-era policies to alleviate unemployment and address the social crisis led to the creation of Hoovervilles, shantytowns that sprang up to house those who had become homeless because of the Great Depression. The towns were named “Hoovervilles,” because of President Herbert Hoover’s ineffective relief policies. Mass unemployment was rampant among men aged 18–50, and the lack of a social safety net continued to push them down the ladder. By looking at the Vanguard’s news coverage from 1930–1932 and the history of Hooverville written by its self-proclaimed mayor Jesse Jackson, we can see that the creation of Seattle’s Hooverville was due to an ineffective social system and the inability of local politicians to address the Depression’s social crisis.

Even though these men wanted to care for themselves, the social structure forced them toward charity, a dependent position many unemployed men in Seattle rejected. As a reporter for The Vanguard, the newspaper of Seattle’s unemployed, wrote of one Hooverville resident, “He had a distaste for organized charity-breadlines and flop-houses so he decided to build a shack of his own and be independent.[1] This rejection of organized charity was due as much to a desire for independence as to the low quality of the shelter and food on offer. While there was shelter for sleeping, it was often on the ground in damp and unhygienic surroundings, and while charities such as the Salvation Army offered soup kitchens, the food was often barely digestible and contained little to no nutritional value. The creation of a Hooverville in Seattle, then, was due to the lack of social safety net, the desire for self-sufficiency, and the poor quality of Depression-era charity.

Jesse Jackson, the self-declared mayor of Hooverville, was one of the men who had a strong distaste for organized charity. After finding men that shared this feeling, they decided to do something about it. In recalling the foundation of their Hooverville, Jackson explained,“We immediately took possession of the nine-acre tract of vacant property of the Seattle Port Commission and proceeded to settle down.[2] Jackson and his friends rounded up whatever they could find and began to create shelters. Seattle city officials were not thrilled about this new development. In an original attempt to disband these shantytowns and unemployed “jungles”, city officials burned down the entire community, giving the men only seven days’ eviction notice. As The Vanguard argued, this only made the social crisis worse: “If the County Health officer orders the Jungles burned out this year, as he did last year, a large number of men will be thrown upon organized charity, for no very good reason.[3] Hooverville residents, for their part, were not thwarted by the city’s attempt to disband them. They simply dug deeper embankments for their homes and reestablished the community. Noted The Vanguard, “Meanwhile, new shacks go up everyday, and more and more buildings uptown are empty.[4]

In June of 1932 a new administration was elected in Seattle. They decided that the Hooverville would be tolerated until conditions improved. However, they did demand that Hooverville’s men follow a set of rules and elect a commission to enforce these rules in conversation with city officials. Among the city’s new rules was one outlawing women and children from living there, a rule almost always abided by. This agreement between Seattle and its Hooverville improved relations between the two greatly. Businesses that were originally hesitant become friendlier, donating any extra food or building supplies to Hooverville’s residents.

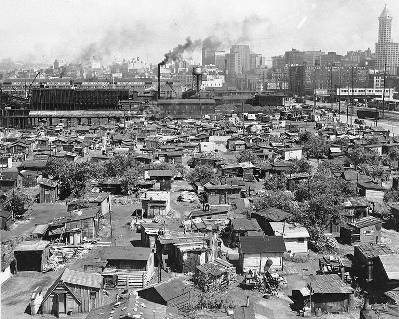

The Vanguard drew vivid pictures of the atmosphere of Seattle’s shantytown: “Little groups of men huddled around forlorn fires, ‘boiling-up’ clothes begrimed by their peculiar mode of travel, or cooking food-the worst kind of food… out of smoke-blackened cans these men eat and drink.[5] While the surroundings were not optimal, Hooverville mayor Jesse Jackson;s more personal portrayal of Hooverville pointed out the resilient nature of residents: “…for the most part they are chin up individuals, travelling through life for the minute steerage.[6] Either way, Hooverville was growing: very quickly after its original settlement, Jackson noted that Hooverville “…grew to a shanty city of six hundred shacks and one thousand inhabitants.[7]

Jackson referred to Hooverville as “…the abode of the forgotten man[8] His characterization was correct in regards to the men who lived in other jungles or shanty communities around Washington, but not accurate of Seattle’s Hooverville. One Vanguard journalist noted that “Perhaps if some of these Jungles were as conspicuous as Hooverville, the problem of unemployment would be recognized to be really serious by those sheltered dwellers on the hilltops who live in another world.[9] The men in the average city jungles were in fact forgotten men. Hooverville, however, was a jungle with power. Wrote sociologist Donald Francis Roy, who lived in the Hooverville as part of his research, “Within the city, and of the city, it functions as a segregated residential area of distinct physical structure, population composition, and social behavior.[10] Residents were not only to gain community involvement but also a place in the Seattle city board of commissioners. Hooverville was becoming a city of its own.

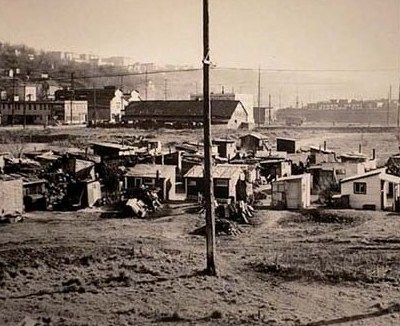

A different Hooverville near 8th Ave S. in 1933 (Courtesy University of Washington Library Digital Collection)..Despite its growing influence in the city, Hooverville was by no means a secure place to live, but a temporary and improvised shantytown. With a backdrop of skyscrapers that boasted of Seattle’s economic might, Hooverville, on the edge of the waterfront, was situated in a location where it stood out completely. One town member commented on how “The sea appears to be eternally licking its chops in anticipation of swallowing the entire community in one juicy gulp[11] While Hooverville’s small shacks seemed to suffice for the time being, they were not sturdy homes. Some were lucky enough to contain solid walls built of wood with separate bedrooms inside, while others barely had a wall and ceiling built from flimsy boards. One journalist described Hooverville simply and accurately as “…approximately one thousand shacks, inhabited by about fifteen hundred men, who have discovered how to exist without money.[12]

The shantytown consisted of almost all men, aged 18–60, with little to no income. Considering that the majority of Hooverville’s population was older men in their 40s, 50s, and 60s, many historians have been shocked that there weren’t higher death rates. Some observers of the community claimed that the shanty lifestyle provided a stability that actually improved some of the men’s health. The only variable among these men was race, which was reflected in Hooverville’s elected board of commissioners. As Jackson wrote, “The melting pot of races and nations we had here called for a commission of several races and nations. Two whites, two negroes, and two Filipinos were selected.[13] As noted before, the Seattle city commissioners did not allow women or children to live in the community. While some floated in and out, they were rarely permanent fixtures.

The spirit of these men was their most notable characteristic. Jackson declared that “If President Hoover could walk through the little shanty addition to Seattle bearing his name, he would find that it is not inhabited by a bunch of ne’er do wells, but by one thousand men who are bending every effort to beat back and regain the place in our social system that once was theirs.[14] Jackson’s goal was to point out that these men were not lazy, but simple, average, hardworking men who had been failed by the social system. While these men created a community together, Jackson felt that a community sensibility was not the only one in the town: “I would say it is more of an individualistic life, but we do divide up a lot around here, but it is more a settlement of rugged individualist.[15] One of the traditions of Hooverville was for residents who found a job (a rare event), to ceremoniously give their house, bed, and stove to others still out of work. While the men of the community clearly were used to living their lives independent of others, they still found a way to help those struggling around them.

The political structure of Hooverville was based largely around the self-declared mayor Jesse Jackson. While the city did demand that the town create a commission of representatives, Jackson was still looked upon as the voice of Hooverville. Jackson claimed that “mayor” was never a role he sought out, but rather fell into: “I am just a simple person, whose status in life is the same as theirs, trying to do the best I know how to administer in my poor way to their wants.[16] The only benefit he received for being the leader of this shantytown was a donated radio from a Seattle company, which he made available to the men by hosting news and entertainment listenings in his shack. While the community seemed to have a substantial political structure, individually Jackson noted that the situation was different. “My honest opinion is that the average working man doesn’t know what he wants in a political way.[17] The community’s naïve opinion toward politics might have been the reason why it was so easy for them to look to Jackson to lead of the community. While there were no laws established within Hooverville, there were common rules enforced. Jackson pointed out one example. “You can’t come here and do just what you want. You can’t live alone. You have to respect your neighbor, and your neighbor must respect you.[18] He noted that troublemakers were not thrown out by the men within Hooverville but by outside authorities.

The men in Hooverville did far more to help themselves than any established social and political structures did during the onset of the Depression., but their collective action was often not enough. One Seattle journalist still put it most bleakly by describing the men of Hooverville’s future as “… blacker than the soot on the cans [they eat out of],” while politicians quibbled … “about the exact number of unemployed but do nothing to relieve distress.[19]

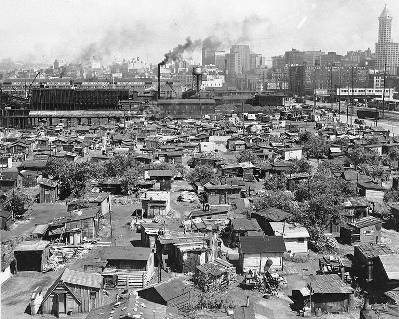

Lee took this photo June 10, 1937. Close to 1,000 men lived in Seattle's Hooverville. (Courtesy University of Washington Library Digital Collection).

Many politicians looked away at other, more “important” issues, but it was still noted that there was a crisis of housing taking place. Reported The Vanguard, “According to the report of the Central Housing Committee of the U[nemployed] C[itizens’] L[eague] to the central federation the unemployed are expected to be content with shacks, rookeries hovels in brief, a pig-pen standard of housing.[20] Politicians, in some cases, did far more harm then good. For instance, after ordering the burning of Hooverville, Mayor Dole of Seattle proceeded to evict more people out of their homes. He suggested that they obtain temporary, low-quality housing, then move quickly into permanent housing again. Articles in the Vanguard asked, “Just where they were going to find permanent dwellings, when they had no money to pay rent in their previous homes, was not explained.[21] This plan was clearly flawed and poorly thought out: “…he was going to see to it that property was protected. Human rights apparently came second.[22] Mayor Dole claimed he was just upholding the rule of law. However, in a time of economic depression, with hundreds of thousands of American’s struggling to make ends meet, what is the duty of the law? It was established the protect individuals, not persecute them when they are down and out. “All these men ask is a job, and until that job is forthcoming, to be left alone.”[23]

Lessons from Hooverville still have not been learned today. Seattle, in 2009, is currently facing a recession that may be the most serious since the Depression of the 1930s, and a community similar to Hooverville has formed. The current “Nickelsville” is a nod to Seattle Mayor Greg Nickels, just as “Hooverville” was a sarcastic nod to President Hoover’s inaction. Additionally, the mission statement on Nickelsville’s website is eerily reminiscent of the Jackson’s description of Hooverville’s founding: “

Nickelsville will keep operating due to the inescapable fact that there are people on the streets with nowhere better to go. They are taking the initiative to organize so they can provide for themselves a basic level of safety and sanitation when their government steadfastly refuses to do so for them.[24] Sinan Demirel, executive director of the local Seattle shelter R-O-O-T-S, which has supported Nickelsville, referenced the history of tent cities in an interview, saying,

“Like the Tent Cities that preceded it, Nickelsville is part of a long and proud tradition of homeless persons organizing themselves to provide each other safety and to educate the broader community about their plight.[25] The leaders of Nickelsville urge its members, as well as the members of the community, to encourage government action to fight homelessness. If members of the Seattle community do not take action, they might experience a modern-day Hooverville. Demirel noted that, “If it is successful during its next move [in June 2009] in establishing a permanent site and permanent structures, then Nickelsville will join an even prouder tradition, dating back to Seattle’s Hooverville over three quarters of a century ago.[26] If Seattle does not learn from the example set by Hooverville in the 1930s—that the failure of the social and political system, not individuals, leads to homelessness—it is doomed to allow history to repeat itself.

Copyright (c) 2009, Magic Demirel

HSTAA 353 Spring 2009

[1] Selden Menefee, “Seattle’s Jobless Jungles.” Vanguard, November 25, 1932, p. 1.

[2] Jesse Jackson, “The story of Seattle’s Hooverville,” Calvin F. Schmid, ed., Social Trends in Seattle vol. 14 (October 1944), Seattle: University of Washington Press: 286–293, ref. p. 287.

[3] Menefee, “Seattle’s Jobless Jungles,” Vanguard, p.1.

[4] Menefee, “Seattle’s Jobless Jungles,” Vanguard, p.1.

[5] Nick Hughes, “The Jungle Fires are Burning,” Vanguard, November 1930, p. 1.

[6] Jackson, “The Story of Seattle’s Hooverville,” p. 291.

[7] Jackson, “The Story of Seattle’s Hooverville,” p. 286.

[8] Jackson, “The Story of Seattle’s Hooverville,” p. 289.

[9] Menefee, “Seattle’s Jobless Jungles,” Vanguard, p.1.

[10] Donald Francis Roy, Hooverville: A Study of a Community of Homeless Men in Seattle, unpublished thesis, University of Washington, Seattle (1935), p. 20.

[11] Roy, Hooverville, p. 21.

[12] Menefee, “Seattle’s Jobless Jungles,” Vanguard, p.1.

[13] Jackson, “The story of Seattle’s Hooverville,” p. 287.

[14] Jackson, “The story of Seattle’s Hooverville,” p. 289.

[15] Jackson, “The story of Seattle’s Hooverville,” p. 292.

[16] Jackson, “The story of Seattle’s Hooverville,” p. 291.

[17] Jackson, “The story of Seattle’s Hooverville,” p. 292.

[18] Jackson, “The story of Seattle’s Hooverville,” p. 293.

[19] Hughes, “The Jungle Fires are Burning,” Vanguard, p. 1.

[20] “Housing problem ignored by county commissioners.” Vanguard, 19 August 1932, p. 1.

[21] “Housing problem ignored by county commissioners,” Vanguard, p. 1.

[22] “Housing problem ignored by county commissioners,” Vanguard, p. 1.

[23] Menefee, “Seattle’s Jobless Jungles,” Vanguard, p.1.

[24] Nickelsville website, “Welcome to Nickelsville Seattle,” accessed May 2009, <http://www.nickelsvilleseattle.org/>.

[25] Demirel, Sinan, interview with author, R.O.O.T.S. Young Adults Shelter, Seattle, Washington, May 2009.

[26] Demirel, interview, May 2009.