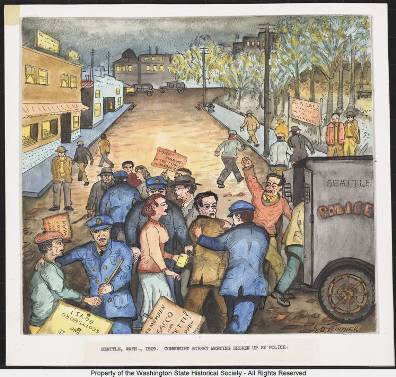

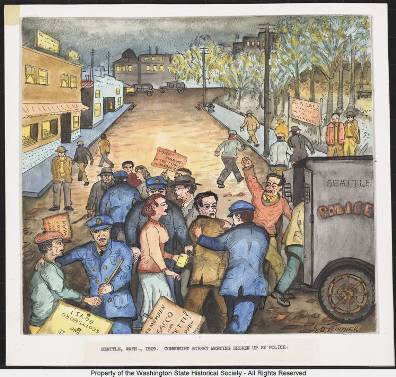

Ray Ginther's watercolor shows police arresting Communist Party members for attempting to hold a protest meeting on the public streets of Seattle in 1929. Violations of basic civil liberties were very common in the early years of the Depression. Before Senator Joseph McCarthy’s famous and insidious campaign in the 1950s that sought to obliterate any trace of leftist “reds” in Washington and in America, there was Big Fish and his Congressional Committee. Hamilton Fish Jr. (III) headed the Special Committee to Investigate Communist Activities in the United States, and in the early 1930s, the Committee traveled across the nation and held hearings in many major cities, including Seattle. Fish understood communism as a triple threat: political, religious/moral, and economic.[1] From a political perspective, communism represented a public menace. Moreover, Russian imports apparently posed a serious problem to American industry. This included the timber industry, the single largest industry in the Northwest and the employer of a large percentage of laborers in the Seattle area. Due to these two perceived threats, Fish and his Committee set out to explore the area, arriving in Seattle in October of 1930. During the process of investigation, the Committee endorsed an understanding of communism that was at once very negative and nearly entirely inaccurate. However, their skewed picture of communism in combination with a rhetoric that inspired fear and paranoia was used to promote America’s economic interests during the Great Depression era.

Ray Ginther's watercolor shows police arresting Communist Party members for attempting to hold a protest meeting on the public streets of Seattle in 1929. Violations of basic civil liberties were very common in the early years of the Depression. Before Senator Joseph McCarthy’s famous and insidious campaign in the 1950s that sought to obliterate any trace of leftist “reds” in Washington and in America, there was Big Fish and his Congressional Committee. Hamilton Fish Jr. (III) headed the Special Committee to Investigate Communist Activities in the United States, and in the early 1930s, the Committee traveled across the nation and held hearings in many major cities, including Seattle. Fish understood communism as a triple threat: political, religious/moral, and economic.[1] From a political perspective, communism represented a public menace. Moreover, Russian imports apparently posed a serious problem to American industry. This included the timber industry, the single largest industry in the Northwest and the employer of a large percentage of laborers in the Seattle area. Due to these two perceived threats, Fish and his Committee set out to explore the area, arriving in Seattle in October of 1930. During the process of investigation, the Committee endorsed an understanding of communism that was at once very negative and nearly entirely inaccurate. However, their skewed picture of communism in combination with a rhetoric that inspired fear and paranoia was used to promote America’s economic interests during the Great Depression era.

National Perspective

In the early 1930s, the United States was experiencing a period of turmoil. Americans were still dealing with the aftermath of World War I, one aspect of which was an unstable economic situation, and this state of affairs left the ground fertile for “radical” ideas to take root. The Great Depression wreaked havoc on American industry, and a great number of people were left without wages, food, or homes. At least eight million people were unemployed in America as of 1930, and many laborers were also poverty stricken due to dramatic decreases in wages.[2] This created a climate of unrest; as a result, destitute workers and the unemployed participated in various organized activities to protest their common plight, including rallies, meetings, and demonstrations that took place in the centers of industry—the cities—across the nation.[3] Moreover, as the number of protests increased, so too did repression from the government:

During the first three months of 1930, the ACLU reported a total of 930 arrests involving free speech cases, exceeding the total for any entire year from 1921 to 1929. During the entire year of 1930, the number of free speech prosecutions exceeded the entire period 1924-29, while the number of meetings broken up by police exceeded by far the total for any year during the 1921-29 period.[4]

These arrest numbers are evidence for how the protests in American cities were greeted by the police force and by the political system: the demonstrations created problems for the police as well as for industry. Therefore, participation in such activities was painted as explicitly radical, un-American and unlawful, indicated by the fact that anti-syndicalism and anti-insurrection laws were increasingly resorted to as justification for arrests.[5] However, many organizations, including those associated with organized Communism, appealed to a large number of destitute American workers.

Indeed, according to historian Robert Justin Goldstein, the Committee to Investigate Communist Activities in the United States was instated as a result of an increase in unemployment demonstrations in connection with communist activities. A number of organized efforts to help the unemployed and poverty-stricken working class were at the time carried out largely by organizations associated with communism, and by the Communist Party (CP) in particular: “of fifty-two meetings broken up by police across the country during the first three months of 1930, forty-three of them were conducted under communist sponsorship.”[6] Indeed, during the spring of 1930, as massive unemployment protests erupted in New York City, sponsored by Communist-led organizations, and the city Commissioner charged that the Amtorg Corporation was distributing communist propaganda, the House of Representatives voted two hundred ten to eighteen in favor of authorizing a committee to investigate subversive activities in America.[7] The goals of the Committee were stated as follows: to investigate “all groups or individuals ‘alleged to advise, teach, or advocate the overthrow by force or violence the government of the United States or attempt to undermine our republican form of government by inciting riots, sabotage, or revolutionary disorders.’”[8] The government understood communism not only as an ideological structure under which workers had the opportunity to unite and promote their agenda, but as an insidious form of indoctrination that would destabilize the very structure of American society.

As the head of the Committee to Investigate Communist Activities, Hamilton Fish Jr. advanced a tenebrous understanding of communism that confused the theory with the supposed application thereof in Soviet Russia. Fish considered communism to be “the most far-reaching issue in the world, affecting the civilization of the world and the happiness and safety of our people.”[9] Fish’s regard for communism knew almost no bounds, but he was by no means focusing on its merits when he wrote “The Menace of Communism” in 1931. According to Fish, communism was an idea originating with foreigners, and argued that eighty percent of communists in the United States were either aliens or naturalized citizens and “took their orders direct from Moscow.”[10] The idea of communism and the practices of Soviet Russia were inseparable for Fish, and he appeared to believe that the recent demonstrations taking place throughout the nation were due primarily to foreign involvement. Fish also claimed that among the several principles of communism, there were intentions to not only abolish religion, but personal property and personal liberties as well, effectively “wiping out all civil rights, freedom of speech, of assembly, and of the press, trial by jury, and so on.”[11]

For the freedom-loving American people, Fish had already established an us-versus-them mentality in his rhetoric by incorporating what Soviet Russia had done to restrict human rights with what communism in general apparently aimed to do. He took it further, however, by implying that the Communists intended to promote “strikes, riots, sabotage, and industrial unrest” as well as class hatred in order to reach these aims.[12] Thus, the protests taking place in America could effectively be understood as the first step in the establishment of a communistic regime that would work to overthrow the government of the United States. Finally, according to Fish, the Communists planned to establish a Soviet-type government headquartered in Moscow “which has for its final objective the destruction of all democratic forms of government and all capitalism throughout the world.”[13] Indeed, the economic aspect of the communist agenda was most worrisome for Fish: “[it is] Russian competition in the world markets that we have to fear.”[14] While he did “not believe that there was any likelihood of a Communist Revolution in the United States,” he regarded Lenin’s Five Year Plan as a threat to the capitalist world market to which American industry was intrinsically tied.

Therefore, Fish proposed certain legislation that he asserted would strengthen America’s flagging economy, including an embargo on Soviet Russia’s imports. He believed that Soviet Russia was in large part responsible for the economic downturn; Russia’s cost-effective imports were undermining the market value of certain American goods and leaving them with unsold higher-cost goods. Some of the national industries purportedly undercut by cheap Russian imports were timber, manganese, pulpwood, anthracite, and matches.[15] The President of the American Manganese Producer’s Association, J. Carson Adkerson, perhaps explained the problem best:

"The Russian policy of dumping manganese ore in the American market . . . sold without regard to price and cost production . . . is wrecking the American Manganese industry and has just recently caused the major producers of this country to close their mines and plants, throwing thousands of men out of employment. This situation is due entirely to the Russian program."[16]

The same could be said for other industries affected by the importation of Russian goods: the more cost-effective Soviet products undermined the market value of American commodities and thus threatened to destabilize certain markets. Moreover, since there was an existing “tariff law which forbids entrance of goods produced all or in part by convict [or slave] labor,” those for whom Russian imports were a threat used this law as the basis for their argument to ban Russian imports.[17] Fish, like many leaders of industry, claimed that the “Communists in Russia . . . are not employed in the capacity of free men and women, but as serfs, shackled and harnessed to the job, receiving about 20 cents gold a day, not permitted to strike, but simply to work and obey orders.”[18] In essence, arguments for an embargo on Russian imports situated themselves in anticommunist rhetoric that played on public fears, while also linking the unstable economy to the communist threat.

Ideology is perhaps one of the greatest governmental weapons used to gain the support of the populace, particularly in times of war or great hardship. America is no exception. In the early 1930s, when the Great Depression was ravaging the nation, a certain national rhetoric was being created in which “if one sees anything worth while that the Soviet Government is doing and correctly reports it, he is, in the eyes of the fanatical anti-liberal or reactionary groups in America, instantly a Communist who seeks to overthrow this Government.”[19] The negative claims Fish and his ilk made about the Soviet system worked to conflate communism with the overthrow of the government and destruction of American industry, and worked to greatly sway public opinion against communism or radicalism.

Local Perspective

The seed for the anticommunist rhetoric which ‘Ham’ Fish was planting in early 1930s America is perhaps even more apparent when viewed from a local perspective. In the greater Northwest area, timber and pulpwood were the largest industries, and therefore the principal employers: “The lumber industry of western Oregon and Washington represents the basic industry of the region as regards to employment. . . [I]t supports approximately 65 percent of the pay rolls of these two states.”[20] It was claimed by several leaders of industry in the Seattle area that Russian imports were undermining local production value and threatening the viability of locally produced goods. This argument became central to the Committee hearing that took place in Seattle on October 3, 1930, and there was an attempt made to connect Russian imports with slave labor as well. In addition, communism was linked to “seditious” activity in the area, and it was further implied that everyone who had anything to do with either communism or the Soviet Union was desirous of the overthrow of the government of the United States.

As the largest employer in the area, the timber industry was very important, so the claim that it faced virtual annihilation due to the importation of Russian lumber and pulpwood was serious, especially during the Great Depression when so many people were already losing their jobs and living in poverty. When the Committee came to Seattle, moreover, several testimonies were given in support of that claim. Ralph Shaffer of The Shaffer Box Company in Tacoma stated that at $17.50 a cord, including the price of delivery, Russian pulpwood “was about from $4 to $5 or more a cord lower than the prices they [East Coast paper companies] had been paying for local pulpwood or pulpwood coming from Canada.”[21] East Coast paper companies were buying the cheaper Russian pulpwood, and this “has forced us to come down in our prices very materially, so that pulp mills in the Northwest are either selling at cost or less than cost or piling their pulp, or shutting down.”[22] In effect, as a member of the Committee stated, it was “injuring . . . business and hurting wages.”[23] The lumber industry was distressed as well; as W.B. Greeley, the secretary-manager of the West Coast Lumberman’s Association testified,

"[T]he lumber industry at the present time is seriously depressed from the inability to market its products. Our mills are now running at less than one-half of their normal capacity; our logging camps are operating at not over 40 per cent of their normal capacity and, in the two States [Washington and Oregon], probably between 40,000 and 50,000 logging-camp and sawmill workers are now without employment; which, of course, adds greatly to the general depression."[24]

Greeley explained that this decrease in business was due to competition with Russian lumber. As one local newspaper observed, Greeley’s testimony, among others, implied that the “Northwest [f]aces [r]uination [and] virtual extinction . . . thru unfair competition from Russia.”[25]

In addition, several testimonies linked Russian imports with convict or slave labor, and local news supported this claim. Greeley was perhaps the most vociferous and stated that “in the last analysis . . . this convict-made lumber from Russia represents competition between forced labor and American labor . . . 50 per cent [of which] . . . price received by the manufacturer represents labor costs.”[26] Greeley did not offer any concrete evidence for his claim, but he went on to propose that the production of Russian lumber cost the Soviet government nothing, due to the fact that the lumber had either been produced through convict or slave labor or had been “confiscated at the time of the revolution.”[27] Local newspapers bolstered this claim as well, and one particularly effective article involved the testimony of one “Aaron Kopman, a U.S. citizen sentenced to a Soviet forced labor camp for selling things in Russia.”[28] Kopman maintained that “each group of 3 [prisoners] had to prepare fourteen logs of heavy timber each day. The logs were at least 3 feet in diameter and at least thirty-three feet long. To heap the logs in even piles took us sometimes as long as fourteen hours.”[29] In essence, the convicts were forced to labor without pay for up to fourteen hours a day every day. Kopman also implied that women in the camps were being raped by the Russian overseers and that he could hear their cries in the camp.[30] He stated that it was “under these conditions that Soviet lumber is produced which is flooding world markets.”[31] Kopman’s story offered a tale of woe to the public in which the Soviet government was the villain.

This was exactly the kind of testimony the Committee was looking for, and when it was not forthcoming, they supplied the witnesses with information themselves by asking leading questions. Although Ralph Shaffer had said nothing in regards to Soviet forced labor camps, the Committee addressed him as follows: “Your complaint is of the interpretation of the law by the Treasury Department; you think they ought to keep out that Russian pulp unless they prove it was not produced in any way by prison labor?”[32] Shaffer agreed with this statement, although his argument had been concerned mostly with the pulpwood industry in the Northwest. Like Greeley had originally claimed, however, the understanding was that “[u]nless the government halts the importation of Russian pulpwood and lumber produced by convict or drafted labor, the lumber industry of the Northwest faces extinction.”[33]

However, there were many contradictions in the testimonies of both Shaffer and Greeley, and neither of them could draw a straight connection from Russian imports to the flailing timber market. Shaffer actually maintained that

"the manufacture of pulp in this particular section of the country has grown considerably in the last four years. . . [d]uring [which] time a little pulpwood has been exported . . . to the eastern part of the United States… [N]o attempt has been made to sell pulpwood [there], on the account of the difficulty of transportation of same, the loading of the vessels and the discharging of the same at the other end."[34]

Therefore, in contrast to other “evidence,” the pulpwood industry in the Northwest region had actually grown, and the markets on the East Coast, where the purchase of Russian pulpwood took place, had, in reality, little impact on the local market because it was not feasible to export local pulpwood to the East Coast without a great deal of expense. Furthermore, Greeley explicitly stated that “[t]he actual volume of these imports [Russian lumber] up to the present time has not represented a particular burden upon our domestic lumber industry.”[35] That statement is very straightforward. However, in his continued testimony, he asserted that it was the intent of the Russian government to expand their lumber industry “from the present figure of about three and one-half billion feet annually to a total of about 12,000,000,000 feet,” and this potential increase, Greeley implied, would seriously jeopardize the Seattle area’s lumber industry.[36] He also suggested that the increase in Soviet imports constituted a plan by the Soviet government to take over the worldwide timber industry entirely.[37] Therefore, even though he had stated that Russian imports had little effect on local exports, the emphasis was placed on a hypothetical situation, drawing a weak line from Soviet Russia’s insidious plans to take over the timber market to the floundering economic situation in the Northwest region of America.

Finally, the testimony of several people in the Seattle hearings linked local “seditious” activities with Soviet Communism. The Chief of Police, Louis J. Forbes, indicated that Communists were law breakers who had advocated the overthrow of the U.S. government. He stated that “[t]he city ordinance requires that any parade held in the city shall have a police permit . . . [and] must have an American flag in the front of the parade.”[38] However, Communists had attempted to hold parades without permits and had not even asked for them. Furthermore, they had promoted “the overthrow of the Government and society by force” many times.[39] Even though, according to George David Hanrahan, a member of the Communist Party and a local “agitator,” the Communists intended to take over mills and factories by peaceful political action in order to put the means of production in the hands of the workers, the Committee got him to admit that he would employ violence if necessary. After a series of leading questions, the Committee asked what Hanrahan would do if an owner refused to vacate the premises after workers had taken control. They asked him if he would shoot the man, and Hanrahan responded, “We would be the government. . . we would use whatever force was necessary to establish the new government.”[40] The indications the Committee wished to imply were that Communists in America would use violence in a revolution to overthrow the government and that they would employ “strikes, riots, and sabotage” in the meantime in order to create “industrial unrest” that would destabilize America’s economy.[41]

Despite the fact that the fault for the economic depression lay not with Communism but with the American economy, during a time of hardship it was perhaps easier to blame the foreign element than the one close to home. It is obvious that the Committee to Investigate Communist Activities in the U.S. intended to place the blame for the Great Depression on Soviet Russia, and by association, on organized Communism. In order to do so, they planted the seeds of an anticommunist rhetoric that used fear to evoke a response from the public. One local newspaper put it this way: “The Ham Fish Red Scare has caused visions of millions of marching reds to terrify the dreams of the readers of metropolitan dailies . . . [and] jobless men and women . . . have been represented . . . as militant armies of reds marching on state capitals.”[42]

In the turbulent atmosphere of the Great Depression era, when so many people in America were suffering, it was perhaps easier for government officials to understand the protests and demonstrations as products of foreign intervention rather than as responses to the failures of the American economic system. Rather than acknowledge that America’s economy was by and large responsible for the Depression, many people, especially those associated with industry, politics, or the law, chose to focus on the issue of communism in the U.S. and Russian imports. In reality, this was but a very miniscule part of a much larger problem, but, nevertheless, the anticommunist ideology planted by Hamilton Fish and his Committee later sprouted into an insidious tree: the rhetoric pioneered by Fish was used by his successors during the Cold War years to promote a climate of fear and repression that dwarfed Fish’s efforts of the 1930s.

Copyright (c) 2009, Crystal Hoffer

HSTAA 353 Spring 2009

[2] Hamilton Fish, Jr., Investigation of communist propaganda. Hearings ... pursuant to H. Res. 220, providing for an investigation of communist propaganda in the United States, Part 5, vol. 1, Seattle, Wash., October 3, 1930, Portland, Oreg., October 4, 1930, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office), p. 44.

[3] Frank J. Donner, Protectors of Privilege: Red Squads and Police Repression Urban America (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1990), 44.

[4] Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America from 1870 to the Present (Cambridge, MA: Schenkman, 1978), p. 202.

[5] Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America, 202.

[6] Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America, 204.

[7] Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America, 200-201.

[8] Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America, 200-201.

[9] Hamilton Fish Jr., “The Menace of Communism,” The Annals, ???? not sure how to do this one

[15] “Soviet Manganese Closes Mine Here: Embargo is Sought,” New York Times….

[17] “Trade War Forecast” Los Angeles Times, p. ?

[18] Hamilton Fish Jr., “The Menace of Communism,” The Annals, p. 3

[19] Burton K. Wheeler, “Communist Rule Severe but Sincere,” Seattle Post Intelligencer,

[20] Testimony of W.B. Greeley quoted in Fish, Investigation, 30.

[21] Testimony of Shaffer, quoted in Fish, Investigation, 21.

[22] Testimony of Shaffer, quoted in Fish, Investigation, 25.

[23] Eslick quoted in Fish, Investigation, 25.

[24] Testimony of Greeley, quoted in Fish, Investigation, 30.

[25] The Seattle Star, Vol. 32:No. 190, (October 4, 1930): 3.

[26] Testimony of W.B. Greeley quoted in Fish, Investigation, 31.

[27] Testimony of W.B. Greeley quoted in Fish, Investigation, 31.

[28] The Argus, Vol. 37:No. 37 (Sept. 27, 1930).

[29] The Argus, Vol. 37:No. 37 (Sept. 27, 1930).

[30] The Argus, Vol. 37:No. 37 (Sept. 27, 1930).

[31] The Argus, Vol. 37:No. 37 (Sept. 27, 1930).

[32] Nelson quoted in Fish, Investigation, 23.

[33] “Russian Convict Lumber Called Northwest Peril,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Vol. 49: No. 137 (Saturday October 4, 1930).

[34] Testimony of Shaffer, quoted in Fish, Investigation, 19.

[35] Testimony of Greeley, quoted in Fish, Investigation, 29.

[36] Testimony of Greeley, quoted in Fish, Investigation, 29.

[37] Testimony of Greeley, quoted in Fish, Investigation, 29.

[38] Forbes, quoted in Fish, Investigation, 2.

[39] Forbes, quoted in Fish, Investigation, 5.

[40] Hanrahan, quoted in Fish, Investigation, 55-56.

[42] “Tramping Hoard of Jobless are Called ‘Reds,’” The Spark, Vol. 3:No. 3 (May 6, 1929): 3.

Ray Ginther's watercolor shows police arresting Communist Party members for attempting to hold a protest meeting on the public streets of Seattle in 1929. Violations of basic civil liberties were very common in the early years of the Depression.

Ray Ginther's watercolor shows police arresting Communist Party members for attempting to hold a protest meeting on the public streets of Seattle in 1929. Violations of basic civil liberties were very common in the early years of the Depression.