by Roxana Johnson

Japanese American children with the children of Scandinavian and European immigrants in Port Blakely, WA, in 1925. The children of Japanese immigrants, known as the Nisei, found themselves excluded from American culture because of anti-Asian sentiment, unlike the Scandinavian American children. The Nisei employed numerous strategies to forge a positive identity for themselves. Through civic organizations and community newspapers, like Seattle's Japanese-American Courier, the Nisei advocated all Nisei to "be good Americans" in order to claim their position within American culture. Click photo to enlarge. (Photo Courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry)

With anti-Japanese sentiments in Seattle in the 1930s, the second generation, American-born Japanese, the Nisei, were faced with the burden of proving their loyalty as natural citizens of the United States. Many young Japanese Americans felt that total assimilation to American ideals was necessary to earn respect and equality in the eyes of white Americans. The Japanese-American Courier, with the support of the Seattle chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League, not only was a newspaper written by and for the Nisei, but also acted as a guide to American assimilation, by publishing editorials and highlighting examples of model youth, encouraging the young Nisei on how to be good Americans. In the eyes of these citizens, the very definition of being a good American was to first demonstrate absolute allegiance to the United States and second, to strengthen the cultural backdrop of America.

The Nisei faced many problems as the second generation Japanese of in America. They had gone to American schools and spoke English fluently, but could not escape from persistent racial discrimination. Because of their race, it was impossible for Japanese Americans, as opposed to, for example, Irish Americans, to wash away their ancestry once they came to the United States and be seen as only American. Changing one’s name was not enough to override the obvious physical characteristics that set the Japanese Americans apart from Americans of European descent.

Even very young Japanese American children felt the injustice of racial discrimination. In 1906, for five months, all “Oriental” children, based on their parentage and not their origin of birth, were ordered by the Board of Education to be pulled out of their schools and be segregated into “Oriental” schools.[1] The parents of these children, first generation Japanese immigrants known as the Issei, fought adamantly for their reintegration into public schools. Their argument was, “The Nisei never could be expected to be good Americans if they were not permitted to associate freely with Americans of other racial and ethnic backgrounds, and if they were to be segregated on the basis of race.”[2] The parents wanted to spare their children from experiencing the prejudices that were forced upon them. In successfully overturning the order of school segregation, the first generation Issei encouraged their children to make the most of the opportunities that they never had. The Issei felt their children were the “pioneer generation,” who must “carry on the proud heritage of our forefathers to make contributions to American life.”[3]

The Japanese American Citizens League was officially established in 1930 by a group of Nisei college graduates who were tired of being discriminated against because of their Japanese ancestry. They had been born and raised American yet had to struggle daily to affirm their patriotism toward the United States. They formed the Japanese American Citizens League in an effort to unify the Nisei and to help the second generation assimilate to white ideology.[4] This group believed that the complete immersion of Japanese Americans into the white community was the only way to rise above any misconceptions or suspicions that white Americans may have had about the Nisei. Dr. Thomas Yatabe, an original founding member, was one of the many Japanese school children forced to leave their schools and attend a segregated school.[5] Despite the injustice he experienced, he felt the Japanese American Citizens League should devote their energy to promoting positivity among the Nisei, rather than retaliating against anti-Japanese sentiment.[6] Today the Japanese American Citizens League continues to thrive with several chapters throughout the West Coast, including Seattle.

James Sakamoto shared the same attitudes as Dr. Yatabe and the Japanese American Citizens League and wanted to strengthen “positive Americanism” among the Nisei.[7] Sakamoto founded The Japanese-American Courier, a local Seattle-area newspaper, in 1928.[8] He felt that, in conjunction with the Japanese American Citizens League, there was a need for Japanese Americans of Seattle to have a mouthpiece and to be heard.[9] This eventually came in the form of a weekly newspaper written entirely in English with its contents mainly concerned with topics and issues that would be of significance to the Nisei.[10] Many articles reported on the activities of the Japanese American Citizens League, but of particular interest are the many articles between 1931 and 1933 that stressed the importance of assimilation to the American—mostly meaning white—way of life.

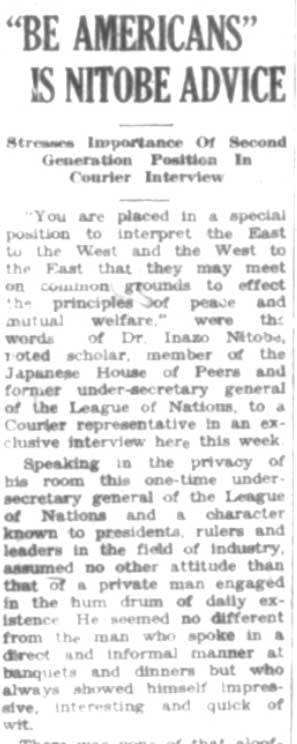

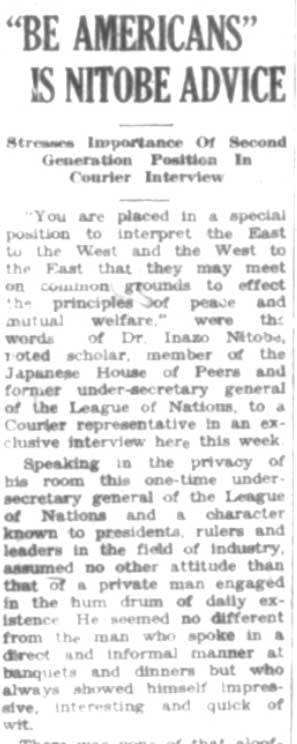

The second generation of Japanese Americans, the Nisei, often portrayed themselves as a cultural bridge between their parents and white American culture, seeking ways to prove their national loyalty by being "200% American." This article is from the front page of the Japanese-American Courier from January 21, 1933.

According to historian Sucheng Chan, the Nisei had several strategies for coping with the dilemmas of being the second generation Japanese in America. The first strategy was to promote the idea that the Nisei must serve as a “cultural bridge between East and West.”[11] For example, The Courier ran an article in 1933 that quoted a young boy commenting on his own perception of his identity as a Nisei: “I think of myself culturally as a child of the Occident…but still racially a child of the Orient…my mission is to interpret the East to the West and to contribute to America the knowledge…”[12] The Nisei felt that retaining some of the knowledge of their ancestral land, while simultaneously being loyal Americans, could be a great contribution to American culture. They felt it was their duty, if they could successfully prove their loyalty to the U.S., to also enrich the landscape of a growingly diverse America and to promote peace and mutual welfare between the United States and Japan.[13]

Besides serving as a “cultural bridge,” however, another very important strategy of The Japanese-American Courier and the Japanese American Citizens League was that the Nisei should strive to be 200% American.[14] A recurring theme of The Courier’s editorials was about how the Nisei had a personal responsibility to set an example of what a model American was. In fact, rather than referring to the Nisei as Japanese Americans, many chose to be referred to as “an American citizen with Japanese ancestry”[15] as a way of negotiating the importance of their American identity while still maintaining the distinction of possessing a Japanese heritage. Thomas Masuda, a writer for The Courier, gave an anecdote in a 1933 issue which illustrated the importance of “individual conduct.” He wrote,

"If a Japanese should do something either good or bad, he would be singled out by this fellow countrymen merely as an individual, but by people of other nations he would be singled out as representing the Japanese. To be more specific, let us assume that a certain Japanese is a very disagreeable fellow. A Japanese would say ‘What a disagreeable fellow he is,’ but an individual of another nation would say, ‘What disagreeable people the Japanese are.’ This is but a single illustration of the importance of individual conduct."[16]

Masuda is explaining to his readers that to be a good American you must be aware that you are representing the Japanese American people at all times. This message was the sad reality for many Nisei at the time; they were only as good as their most “disagreeable fellow.”

Fortunately, not all of The Courier’s articles left the reader with such an ominous outlook or tremendous responsibility. Many of the paper’s articles reported on success stories that were meant to encourage their readers. One article, from 1933, declared that the preferences of the Nisei were “distinctly American.”[17] The second generation, although were accustomed to eating rice at least once a day, now had a propensity for American food. The Nisei also began to have a preference for American song and dance as opposed to traditional Japanese opera. The writer, Tooru Kanazawa, also claimed that the second generation had grown “straight, taller, and better formed than their parents,” which allowed them to take up Western garb rather than the customary Japanese dress.[18] This may have been a strategy of The Courier to congratulate the Nisei that their efforts to assimilate to the dominant ideology were paying off socially and, more incredibly, physically.

An issue of the Japanese-American Courier from July 8, 1933, featured a frontpage article profiling a Japanese American coed who explained how truly "American" she felt. The articles in the Courier sought to promote Japanese or Japanese American identity as a truly American one, a strategy that was both a positive reworking of American identity and a defensive posture in response to anti-Asian sentiments. Click photo to enlarge.

Oftentimes The Courier spotlighted certain youths that were providing a good example for other Nisei in their assimilation toward positive Americanism. An article that ran in 1933 was entitled, “Coed of UCLA Declares She Is Truly American.”[19] The point of running this article was to comfort the many Nisei who felt at odds with the incongruence of white America’s judgment of them based on their race and their own self-perception. This article begins by describing a previous article in the Los Angeles Times entitled, “What Am I—Japanese or American?”[20] They chose to profile a young Nisei named Alma Matsumoto. Matsumoto went on to explain all of the aspects of her life that were “truly American.” Her hobbies included going to football games, dancing, and learning French. She even exclaimed that she loves apple pie and voted for Roosevelt. The girl described her struggle as one of a Nisei who feels thoroughly American yet in the eyes of white Americans was considered “Oriental.” Matsumoto even stated that she felt like an outsider during a four-year stay in Japan. She sadly lamented that “Mine is the situation of the typical second generation Japanese boy or girl in this country.”[21] The article ends on a positive and encouraging note: although many Nisei are in this predicament that America is ultimately their country.

Many felt the pain of constantly having to confirm their American citizenship. Part of being a good American was that although they often felt cast out, the Nisei must always persist to be seen as devoted Americans. The Courier wrote in an article from 1933 that “Perhaps one of the most irritating comments well-meaning women comment of a Japanese is what good English he or she commands.”[22] This type of comment would have been aggravating to anyone born and raised speaking English, let alone a Nisei sensitive to their own ability to assimilate into white American life.

The Courier was quick to publish articles in which the Nisei were complimented by affluent white Americans. One such article, written in 1932 by Juvenile Court Judge Everett Smith, commends Japanese American children for their mental aptitude, politeness, and obedience to authority. Judge Smith signs off his editorial with closing remarks seemingly aimed at fellow white Americans: “We are apt to be quick to detect the faults and deficiencies of other people, and judge them harshly. Let us occasionally look at their virtues and their attainments with admiration and approval. It will help to make us kind and tolerant.” [23] Though the last few sentences appear to be a backhanded compliment toward the Nisei, this article was nonetheless featured on the front page of The Courier.

Although the second generation, as a whole, had above-average education levels, they were relegated to menial labor because of favoritism to white workers during the Depression, a time of soaring unemployment rates.[24] This fostered another strategy outlined by historian Sucheng Chan as the “progressive movement” of the second generation. The “progressives” were interested in labor equality for the Japanese Americans. They did not believe in Asian militancy, had a propensity to reject the status quo, and refused to conform to the prevailing ideology; instead, they encouraged young Nisei to become members of the Japanese American Citizens League to strengthen Nisei community and political and social power.[25]

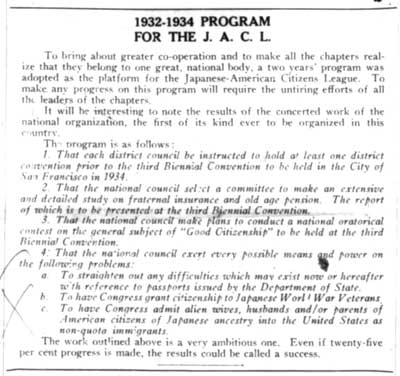

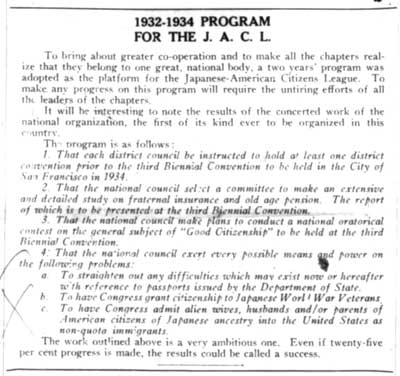

The 1933-1934 program of the Japanese American Citizens' League, printed in the November 1932 edition of San Francisco's Pacific Citizen newspaper (vol. 4, no. 60, p. 1).

The JACL here plans a national contest promoting "Good Citizenship," as well as lobby for political goals aroound immigration and citizenship. Click on the photo to enlarge.

Some articles in The Courier were aimed at easing the tensions surrounding the disparities in labor opportunities for the Nisei. The Courier proudly announced in a 1933 article that one of the largest Japanese-owned vegetable farms in Washington, the White River Valley, employed Nisei alongside white Americans. The article states, “…Harmony prevails, not only among laborers in the fields, but among the employees of the packing sheds where second generation Japanese mingle with their American neighbors of lighter complexion.”[26] This article encouraged the Nisei readers to be proud that they could be economically successful while working with white Americans and without having to resort to direct competition with white laborers for jobs.

The second generation of Japanese Americans in Seattle truly was a pioneer generation. They owed much to their hard-working parents, the Issei, for providing them opportunities as well as the inherited burden of being born racially different from the dominant society. Although production of The Japanese-American Courier was halted during the evacuation of the Japanese in 1941, the resounding message was clear and spoke volumes to The Courier’s belief in assimilation. The most important statement to their readers was to “assume a proper pride in their citizenship as well as in the high heritages of their race and transform what they believe to be their handicap into an advantage.”[27]

At times The Courier would simply report current world news and events, but it also served as a source of inspiration and support for the Nisei. The editorials were meant to promote unity and solidarity among the second generation. It was imperative, The Courier argued, that the Nisei succeed in “cementing the friendship of Japan and America”[28] by acculturating to the white community because this would be the only way to earn equality and respect, while also showing their pride as natural American citizens. Each and every Nisei had the responsibility to make the very best of themselves and to be, above all else, good Americans.

Copyright (c) 2010, Roxana Johnson

HSTAA 105 Winter 2009

[1] Bill Hosokawa, Nisei: The Quiet Americans, (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1969) 86.

[2] Hosokawa, Nisei, 87.

[3] Muraoka Speaker, “Graduates Owe Parents, Chance At Opportunity,” The Japanese-American Courier (vol. V: no. 232) 11 June 1932, 1.

[4] Hosokawa, Nisei, 194.

[5] Hosokawa, Nisei, 87.

[6] Hosokawa, Nisei, 197.

[7] Hosokawa, Nisei, 197.

[8] Hosokawa, Nisei, 182.

[9] Hosokawa, Nisei, 182.

[10] Hosokawa, Nisei, 182.

[11] Sucheng Chan, Asian Americans: An Interpretive History, (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1991) 117.

[12] Tooru Kanazawa, “Brave Boy, Girl Ready to Fight Hard Problems,” The Japanese-American Courier, (vol. VI, no. 286) 1 July 1933.

[13] “ ‘Be Americans’ Is Nitobe Advice,” The Japanese-American Courier, (vol. VI: no. 263) 21 January 1933, 1.

[14] Chan, Asian Americans 117.

[15] Thomas Masuda, “Masuda Stresses Individual Conduct To Bring Harmony,” The Japanese-American Courier, (Special Edition) 1 January 1933, 3.

[16] Masuda, “Masuda Stresses…”

[17] Tooru Kanazawa, “Youths Prefer American Food, Styles, Usages,” The Japanese-American Courier, (vol. VI: no288) 15 July 1933, 1.

[18] Kanazawa, “Youths Prefer…”

[19] Tooru, Kanazawa, “Coed of UCLA Declares She Is Truly American,” The Japanese-American Courier, (vol. VI: no 287) 8 July 1933, 1.

[20] Kanazawa, “Coed…”

[21] Kanazawa, “Coed...”

[22] Kanazawa, “Youths Prefer…”

[23] Everett Smith, “Smtih Praises American Born Japanese Here,” The Japanese-American Courier (vol. V: no.240) 6 August 1932, 1.

[24] Ronald Takaki, A Different Mirror, (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1993) 274.

[25] Chan, Asian Americans, 117.

[26] Hakugyoku Sanjin, “Japanese Farms Aids Employment, Create Wealth,” The Japanese-American Courier (vol. VI: no. 288) 15 July 1933, 1.

[27] “ ‘Be Americans’…”

[28] Masuda, “Masuda Stresses…”