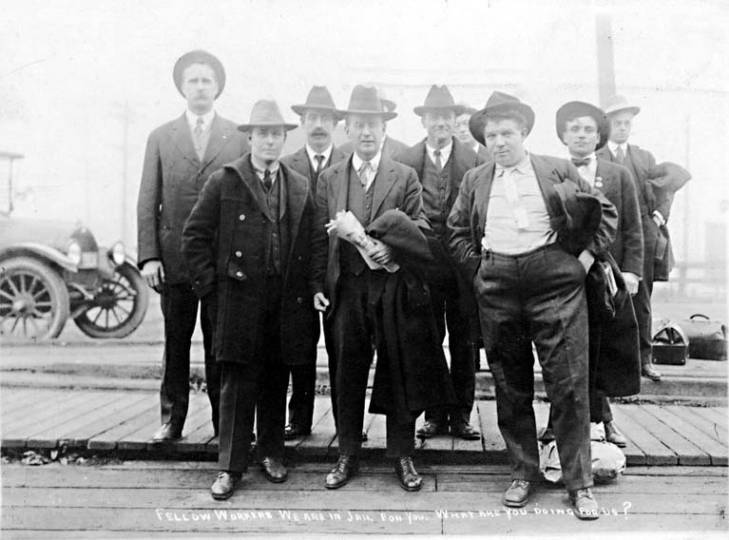

IWW leaders convicted of conspiracy to obstruct the war effort in the Chicago Case, possibly en route to McNeill Island Penitentiary (courtesy UW Libraries Special Collections)

IWW leaders convicted of conspiracy to obstruct the war effort in the Chicago Case, possibly en route to McNeill Island Penitentiary (courtesy UW Libraries Special Collections)

The Industrial Workers of the World were, for a dozen years at the beginning of the 20th century, America’s premier revolutionary leftist organization. Calling them “Beautiful Losers,” anarchist historian Bob Black writes that “the IWW was by any standard as remarkable and radical an organization of any importance as the United States has ever produced. The Wobblies knew it and so did their enemies, who regarded the Wobblies with fear and loathing not unmixed with a certain fascination and grudging respect.” [1]

Founded in 1905, the IWW built a mass membership and achieved important victories in the years leading up to US involvement in World War I. The momentum was checked in 1917 and 1918 when federal authorities accused the organization of sponsoring anti-war activities in violation of the newly enacted Espionage Act. Hundreds of Wobbly leaders were arrested by the Justice Department in 1917 and 1918 and the organization faced further persecution from local authorities, particularly after many states passed criminal syndicalism laws making IWW membership a felony. It is sometimes said that the World War I repression broke the IWW, but in fact the movement survived and in the early 1920s Wobblies were again somewhat effective, especially among agricultural workers and maritime workers. But the comeback ended when the organization split in two during the disastrous General Convention held in Chicago in September 1924. The split did not end the IWW, but in the words of historian Eric Thomas Chester it was now “reduced to a shell of its former self.”[2]

This essay examines the years leading up to the split while assessing the issues and structural dynamics that contributed to the crisis. The collapse of the IWW has traditionally been linked to pervasive and persistent repression. Historians rightly emphasize the roundups, deportations, trials, long prison sentences, and vigilante violence that disrupted leadership and made it difficult for the organization to operate in the open. Historians Melvin Dubofsky and Eric Thomas Chester also delve into internal factors that precipitated the union’s split, which is the approach that will be emphasized here. Tense ideological debates, leadership struggles, and evidence of structural confusion emerge from close reading of primary sources, including the Industrial Worker, the organization’s weekly English language newspaper. I also draw upon John S. Gambs’ 1932 dissertation, The Decline of the I.W.W. which includes long excerpts from IWW documents.[3] These sources suggest the importance of the internal disagreements that wracked the organization in the early 1920s, some based on unhealed wounds that had been plaguing the union for years. The seeds of this conflict were both ideological and practical in scope and exacerbated by personal grudges and power struggles within the persecuted union. Illuminating them allows us to see that the destruction of the IWW in 1924 was the result of unprecedented governmental repression but it was also the result of self-harm, an act of movement suicide.

LEADERSHIP CRISIS

On September 5, 1917, federal agents executed a coordinated raid on IWW offices across the United States, seizing records, wrecking or shutting union halls, and arresting 166 top leaders on secret indictments. Hundreds more were arrested on sedition and other mostly trumped up charges[4] for opposing World War I in the months that followed. The union was additionally subject to the Palmer Raids, America’s first organized red scare, in early 1919. To most Wobblies, it seemed as if it were open season for local police forces to raid their halls. And 1919 would end on an even bleaker note in November when an American Legion attack on a IWW hall resulted in the lynching of member Wesley Everest and the arrest of many other Wobblies.

On Armistice Day of 1919, American Legion members left their parade route and attacked an IWW hall, where they were met with a brief, but bloody gunfight. In the midst of resurgent federal persecution, the Centralia affair would end up causing both immediate and long-term damage for the IWW. The incident was branded as the “Centralia Massacre,” with public opinion casting the IWW as murderous thugs who set an ambush for the American Legion members who had attacked the hall. All in all, by the start of the new decade the Wobblies were in a state of disrepair, hamstrung between trying to defend their fellow workers and not getting arrested themselves. As noted by a lawyer who had represented them, the war years had made “the wobs… nearly extinct.”[5]

Following the arrest and detention of many prominent organizers during World War I, the IWW underwent a leadership crisis lasting many years. A young Philip Taft, who would later distinguish himself as a labor historian, opined in an editorial to the Industrial Worker that “the last few years ha[d] been the most trying in the organization’s history. We have been confronted with issues and problems such as we have never before been called upon to face”[6]. Leaders were prosecuted in mass trials in Chicago and Sacramento while rank and file members fell victim to newly minted “criminal syndicalism”[7] laws in western states. The organization quickly elected new leaders, but the new members of the General Executive Board (GEB) were nowhere near as experienced as their predecessors. Having foreseen this problem, the original GEB had attempted to put together a strong set of replacements before the Chicago trial, but government surveillance allowed the Justice Department to arrest this group.

The leadership changes exacerbated simmering internal conflicts lying within the organization. While most of the old GEB had been centralizers, syndicalists who believed in consolidating power in the union leadership, based in Chicago, the new GEB was dominated by decentralizers, who supported strong local leadership and a weak national apparatus, and whose opinions on how the organization should proceed were vastly different from the previous GEB. Where before the IWW had been ostensibly united behind charismatic leaders like William “Big Bill” Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, the new leaders were now struggling to fill crucial positions. As Melvyn Dubofksy explains, this “leadership drain”[8] impacted the way the GEB responded to the series of crises that unfolded in the years following. While experienced leadership could have righted the ship and weathered the storm, the new, inexperienced GEB was unable to handle internal struggles and facilitate recovery from the external battles the organization was increasingly losing. Despite these ominous tidings, however, the union was not entirely dead. New organizing drives would help provide the badly injured organization a new chance at life.

The early 1920s found two crucial organizing drives buoying the union’s financial hopes and providing organizational direction. The Agricultural Workers’ Industrial Union (AWIU) experienced a surge in membership (and more importantly, $2 membership fees),[9] revitalizing the union’s dangerously small budget. In addition to the AWIU, the Maritime Workers’ Industrial Union (MTW), had undertaken a bold nationwide organizing drive that brought an influx of new members into the union. The MTW had remained strong despite wartime repression, and its largest local, Local 8 in Philadelphia, had even maintained a closed shop on the docks throughout the war. For one year, this seemed to be enough. 1922 saw an uptick in major strikes as well as successful organizing drives and free speech fights from two traditional powerhouse industrial unions. Going off of internal documents and daily happenings as reported in the Industrial Worker, these two efforts should have been enough to sustain the union while leadership was reestablished. Unfortunately, a disastrous attempt at a general strike in early 1923 undid nearly all the financial and morale gains won in 1922.

Funeral for Mrs. Sundstedt, killed by KKK raiding IWW hall in San Pedro, California, June 1924 (courtesy UW Libraries Special Collections)

Funeral for Mrs. Sundstedt, killed by KKK raiding IWW hall in San Pedro, California, June 1924 (courtesy UW Libraries Special Collections)

Following the auspicious beginnings of 1922, 1923 would prove to be a year of destructive defeats on the strike line. Many of the major strikes initiated in the back half of 1922, including ones at Hetch Hetchy Dam and in Portland, eventually fizzled out in the first few months of 1923. Without resounding victories at the end of these actions, the massive amount of resources poured into them began to put a strain on the union’s recently replenished pocketbook. Of all the simultaneous wars of attrition that the union had taken on, the costliest would be a combined strike and free speech fight at the port of San Pedro in Southern California. With persistent raids (including one from the KKK in 1924) and arrests beginning to pile on, the MTW had been forced into a stalemate with the bosses. The strike would simmer on throughout the year and into 1924 as internal battles raged. The job action in San Pedro had been particularly costly because of the high amount of violence endured by the MTW in addition to the criminal syndicalism charges they faced and the financial damages they incurred. As individual strikes began to fail, so too did the year’s general strike. These crushing blows effectively erased the momentum gained in the strikes and organizing drives of 1922. By midyear, the union found itself back where it had started the decade- with little money left and few recent victories to show for it.

However, disaster had also struck earlier when Local 8 of the MTW split from the IWW, ostensibly over a disagreement regarding their $25 initiation fee.[10] Truthfully, though, the local’s departure was one of the first salvos of the rapidly intensifying ideological conflict within the IWW. Accused by union communists of loading ammunition to be used against the Bolsheviks, the GEB suspended the local in August of 1920, only to have their decision reversed by the newly elected GEB in 1921.[11] After months of controversy, Local 8 was eventually expelled from the IWW during the year’s general convention in May. This episode would signal the beginning of tensions within the union becoming out and out political conflicts. With the emergence of the Soviet Union as a lasting power on the left, existing political tensions within the IWW became inflamed.

By nearly all metrics, the IWW was in serious trouble at the start of the decade - not irreparable if the union could band together and set forth a coherent program, but grave nonetheless. The union was now fighting employers on the back foot; as the leadership crisis progressed and internal struggles worsened, local organizers spent less and less time organizing labor actions. Even the union’s current enemies were compelled to admit that the IWW was not as big of a threat as they were being made out to be. Edward W. Graham, a labor spy known as agent #17, wrote a two-year series of reports on the Seattle IWW after he had infiltrated their ranks, ending with the first six months of 1920. In the entirety of those six months, Graham mentions only one proposed strike[12] despite his attempts to inflate membership numbers and finances in reports to his employer.[13]

BOLSHEVIK CHALLENGE

The seeds of the ideological crisis that ended up tearing the IWW apart were planted amidst the debate over whether the IWW should affiliate with the newly organized Red International of Labor Unions (RILU), a Marxist-Leninist council of unions and individual workers led by Bolsheviks. Following the publication of Lenin’s Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder, the RILU condemned the IWW and asked them to, in effect, disband and work by infiltrating AFL affiliated unions.[14] This ultimatum split the Wobblies into three camps: the few remaining communists who by and large left immediately following the initial RILU debate and the centralizing and decentralizing syndicalists who had been in competition for the union apparatus for years. By now the centralizers had begun to espouse a faint degree of sympathy towards the Bolsheviks, putting them even further at odds with the hardline anarchists of the decentralizer faction. Decentralizers framed the RILU debate as akin to being asked to commit suicide[15] on behalf of those oppressing workers. In their eyes then, those who followed the Bolshevik line as set forth in Left-Wing Communism were paid liquidators, boring from within the union to destroy it. In essence, decentralizers declaimed anyone showing sympathy to the Bolshevik vision of communism as “not a real I.W.W. man,”[16] and someone who was betraying the foundations of syndicalism that undergirded the IWW.

Though one might expect these crucial internal debates to have been conducted privately, both factions frequently took to the editorial pages of the IWW’s two major newspapers, Industrial Worker and Industrial Solidarity, to air their views to their fellow workers. The two publications were based on opposing coasts and aligned with their region’s respective ideology. The Industrial Worker, the IWW’s western newspaper, was controlled in 1923 by adamant decentralizers, chief among them writer Jean Sanjour and editor C. E. Payne. While the average reader would not have been able to tell by the relatively unified first pages of the paper, the staff was waging war with other Wobblies on page three. They made their sympathies known, boldly stating “no government shall ever solve the problem of the emancipation of the working class” and as long as any fellow workers disagreed, “they will object to the policies of our paper.”[17] Industrial Solidarity, on the other hand, was split between centralizers and the remaining communists of Chicago and struck a less combative tenor than the Worker. Where once the two newspapers had been official publications of the union during times of unity, now they were a battleground.

In the second half of 1923, longstanding tensions were aroused when Sanjour returned from Russia and began to run a six-month series of articles with Payne criticizing the Soviets for their handling of the end of the Russian Revolution. Starting on July 25th with an editorial entitled “Imprisoned Russians Send Protest Against Their Terrible Treatment” that accused the communists of “crucify[ing] labor,”[18] Sanjour and Payne frequently took the Bolsheviks to task. The Worker primarily took issue with the Russian government’s handling of the Kronstadt Rebellion,[19] Lenin’s New Economic Policy (even going so far as to insinuate that the Soviets were capitalists hell-bent on sabotaging successful workers’ movements),[20] and the RILU’s command to disband.[21] For the first few months, Sanjour and Payne would publish a new article critical of the communists’ handling of the Russian situation every few weeks in attempts to sway fellow workers to the side of the decentralizers[22] in the run-up to the union’s 1923 general convention. On the whole, these articles mostly stuck to propagating anarchist viewpoints of distrust towards all government and declaring the leaders of the Bolsheviks to be opportunists who had sold out the workers for personal enrichment. The Worker’s editorials remained ideological in scope and largely aimed at targets outside of the IWW until readers on both sides started to write in their responses.

As vitriolic arguments developed in the pages of the Worker, suddenly no topic was considered too inflammatory or off limits. In their responses to Sanjour and Payne, both centralizers and decentralizers began to question not only each other’s ideological affiliation and commitment to labor, but also each other’s character. The foremost centralizer critique of the Worker was of Payne’s framing of the Russia articles. The Worker was theoretically supposed to be an official arm of the IWW as a whole, and to centralizers like James Farnham, Payne’s direction was “just the expression of the editor’s ego… with no set policy”[23] regarding the regulation of debate. Centralizers also took issue with both the inaccuracy and ideological slant they thought was apparent[24] in Sanjour’s reports. The centralizer position was best represented by a letter from an anonymous Canadian Wobbly “suggest[ing] that in the future no reports of criticisms of Russia shall be published in our columns unless indisputable proofs can be printed side by side with the facts.”[25] Centralizers like this Canadian took a cautious stance on Russia, proclaiming not to know whether to support them or not, but disapproving of Payne and Sanjour’s editorials as hasty and potentially having done “the workers of Russia a grave injustice.”[26]

Given the Worker’s position, communists wrote in more rarely, though one anonymous fellow worker proclaimed in a letter that “the government of Russia MUST in the name of humanity rule with iron hands.”[27] Implicit in both centralizers’ and communists’ criticisms was the suggestion that the decentralizers were sabotaging the most prominent contemporary workers’ movement through their ideological rigidity. Though less often explicitly mentioned, this resentment also applied to the decentralizers’ opinions of internal organization within the IWW - a resentment that would only grow with the approach of the general convention.

When it came time to respond to the centralizers’ criticism, Payne and his allies took an even more aggressive stance than they had before. Where before he had kept his opinions to policy, now he could sense the shift to the personal[28] and began to adjust the Worker’s course accordingly. In early September, Payne ran an editorial written by a Wobbly who claimed to have been in Russia that accused centralizers of being “paid liquidators” instructed by the Russian government to “bore” the union “from within” [29] in order to sow discontent. This situation was only further inflamed when the Worker published a set of letters from the RILU to the MTW attempting to sway the industrial union to the side of the communists, along with another impassioned rebuttal from Payne.[30] Angered at the subsequent allegations of editorial impropriety, Payne charged his enemies within the union of being “executioners of the workers’ liberation movement.”[31] When they responded again to this claim, Payne ran the centralizers’ argument under the heading “THEIR VIEW” and his own under “OUR VIEW.”[32] Of all the decentralizer articles, however, the most vicious came courtesy of John Perz, a Wobbly who had visited Russia with a group of centralizers. In his column, Perz branded the centralizers as rapists who “did not come to Russia to help build, but to degrade the Russian women.”[33] With the general convention mere weeks away, tensions were at an all-time high. Despite this, the situation would be further worsened by new developments at Leavenworth and San Quentin.

AMNESTY STRUGGLE

While the imprisonment of Wobblies had initially created crisis in the shape of ‘leadership drain,’ the struggle also acquired a new political dimension as questions arose over how the union should deal with large numbers of members enduring long term imprisonment. Horrid conditions, some imprisoned Wobblies having been turned to the side of the guards, and the few previously mentioned bail jumpers created a hostile environment for the remaining ‘class war prisoners.’ These conflicts naturally did not remain constrained by prison walls, as the union’s political factions chose sides and began to argue on what the IWW’s official line should be regarding prison and amnesty. Centralizers partnered with liberal organizations like the ACLU in arguing that the IWW should pile its funds into appealing the convictions from Chicago and Sacramento while decentralizers refused legal action outright. Now, on what was the union’s most pressing issue, rank and file members were practically split in half. While this division was brewing, new developments in the White House would further complicate the question of amnesty.

In the aftermath of WWI, the Wobblies in federal prisons found a relatively less vicious warden in President Warren G. Harding. Harding offered conditional commutations that included a confession of guilt to a large portion of the remaining Wobbly prisoners in the summer of 1923[34] after the prisoners received an upswing in public support. This offer, however, was not extended to many of the decentralizers at San Quentin who had been convicted in Sacramento after refusing to defend themselves,[35] which engendered a great deal of uproar when prominent centralizers in Leavenworth took the deal. In response, the Worker praised the decentralizers[36] and others who had not taken the deal, stating that “it may be shocking to political expediency… that men still live who are willing to sacrifice freedom of person for freedom of principle.”[37] When the centralizing leaders returned from Leavenworth, they encountered a great deal of resentment from those who felt as if they had sold out the principles of syndicalism. The General Defense Committee, the IWW’s legal defense group, briefly brought on former leader Ralph Chaplain for a public relations position before outrage from decentralizers caused him to step down.[38] With the old figureheads of the union released, the battleground for ideological conflict at the general convention was set.

JAMES ROWAN

Key among those in Leavenworth who had refused commutation on principle was former head of the Lumber Workers’ Industrial Union (LWIU), James Rowan. Rowan, an inspirational figure to West Coast Wobblies and an ardent decentralizer, had been sentenced to 20 years in prison. After the Coolidge administration unconditionally commuted the sentences of the 31 remaining Wobblies at Leavenworth, allowing Rowan to return to his post within the LWIU. Rowan held a particularly rancorous grudge against the prisoners who had taken conditional commutations. He (and many others) felt that the commutations were not only a sign of the opportunism they thought was endemic of centralist politics, but a personal betrayal of the fellow workers who had remained in prison. To this end, Rowan’s future direction for the decentralizing faction would be more personal than political. Like Payne’s handling of the Industrial Worker, Rowan’s campaign in 1924 would demonstrate how personal grievances would derail the IWW much faster than any genuine ideological conflict or outside pressure had been able to do.

The 1923 general convention’s moderate centralizing platform failed to account for the year’s polarization and created an environment in which the 1924 split was nearly inevitable. First on the GEB’s agenda for the convention was an unconditional denunciation of the RILU,[39] a move which pushed out the rest of the remaining communists within the union. This position, though harsh, was merely a reflection of the prevailing ideas of western decentralizers who had spent the year raiding the homes of communists and beating them.[40] Despite this, the convention lost the backing of the decentralizers for its implicit approval of prisoners who had taken conditional commutations[41] and its moderate centralizing plan[42] designed to help the union recover and consolidate its precarious position. With this, the IWW was entirely split, with no realistic hope of survival.

Although the IWW made it to the 1924 general convention in September, its demise was already a foregone conclusion. As historian Melvyn Dubofsky put it, the IWW needed “only the slightest nudge to push it over into the abyss of non-existence,”[43] a push which would be gladly provided by James Rowan. Rowan established his own platform for the convention known as the Emergency Program (EP), which took radical stances on decentralization and called for the abolition of the GEB.[44] When the convention was convened in Chicago, the meeting quickly devolved into a shouting match and subsequently, fist fights. The resulting fiasco ended in a court battle initiated by Rowan over the meeting space, with the EP winning and the centralizers being forced to decamp to a new office in the city.[45] To most decentralizers, this was yet another betrayal in the long series of issues. Rowan had given up his decentralizing principles to settle a personal score against the other leadership slate, which was led by two Wobblies who had taken Harding’s conditional commutation.[46] Following this altercation, the disgraced Rowan would be mocked by many of his former followers, who in turn left the EP he had established with their support.[47] By the end of the convention, the official status of the IWW finally reflected what had been developing for years. The militant organization of the early 20th century had been rendered mostly defunct for the better part of a generation by infighting.

In the end, the “beautiful losers” of the American labor movement had revealed the ugly inner workings that had caused its demise. By the time of the split, the IWW had devolved from an effective union to a group of radicals engaged in petty squabbles based on personal slights. The trope of “beautiful losers” has therefore been counterproductive for understanding the union’s death because it obscures the IWW’s penchant for rancorous infighting. The IWW crippled itself for a generation in an act of self-injury because its members were too unhappy with each other to bother salvaging the remaining union apparatus. This outcome was not inevitable. The articles run in the Industrial Worker fanned the flames of issues that could likely have been worked out had the Wobblies come together and weathered the leadership and Centralia crises.

Copyright (c) Cameron Molyneux, 2020

This article began as an assignment for HSTAA 353 Spring 2019 and won an award from the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies and the Pacific Northwest Labor History Association.[1] Bob Black, “Beautiful Losers: The Historiography of the Industrial Workers of the World” (1998) http://www.inspiracy.com/black/beautifullosers.html, p. 11.

[2] Eric Thomas Chester, The Wobblies in Their Heyday: The Rise and Destruction of the Industrial Workers of the World in the World War I Era (Santa Barbara, 2014), 174; Melvyn Dubofsky, We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World (Chicago, 1969)

[3] John S. Gambs, The Decline of the I.W.W. (New York, 1932),

[4] Chester, The Wobblies in Their Heyday (Santa Barbara, 2014).

[5] Dubofsky, We Shall Be All (Chicago, 1969), p. 260.

[6] Philip Taft, “Organization: an Answer.” Industrial Worker, May 13, 1922, p. 3.

[7] Chester, The Wobblies in Their Heyday (Santa Barbara, 2014), p. 207.

[8] Dubofsky, We Shall Be All (Chicago, 1969), p. 260.

[9] Chester, The Wobblies in Their Heyday (Santa Barbara, 2014), p. 209.

[10] Dubofsky, We Shall Be All (Chicago, 1969), pp. 256-257.

[11] Patrick Renshaw, The Wobblies: The Story of the IWW and Syndicalism in the United States. Updated edition (Chicago, 1999), pp. 249-250.

[12] Edward W. Graham, “Labor Spy Report by Agent #17 to Broussais Beck, April 22nd, 1920”

[13] EWG, “Labor Spy Report by Agent #17 to Broussais Beck, January 21st, 1920”

[14] Chester, The Wobblies in Their Heyday (Santa Barbara, 2014), pp. 204-205.

[15] J. Sanjour, “Shall Industrial Workers of the World Commit Suicide?” Industrial Worker, November 14, 1923, p. 3.

[16] J. Sanjour, “Shall Industrial Workers of the World Commit Suicide?” Industrial Worker, November 10, 1923, p. 5.

[17] J. Sanjour, “Criticism of Russia.” Industrial Worker, September 1, 1923, p. 2.

[18] “Imprisoned Russians Send Protest Against Their Terrible Treatment.” Industrial Worker, July 25, 1923, p. 1.

[19] J. Sanjour, “Criticism of Russia.” Industrial Worker, September 1, 1923, p. 2.

[20] “We Read the News.” Industrial Worker, July 25, 1923, p. 3.

[21] J. Sanjour, “Criticism of Russia.” Industrial Worker, August 18, 1923, p. 3.

[22] J. Sanjour, “Situation Deplorable for Russia’s Workers Held in Soviet Grasp.” Industrial Worker, September 19, 1923, p. 1.

[23] James Farnham, “Criticism of Russia.” Industrial Worker, November 21, 1923, p. 3.

[24] Erick Engstrom, “Criticism of Russia.” Industrial Worker, October 6, 1923, p. 3.

[25] “The Criticism of Russia Called Down by Canadian.” Industrial Worker, October 17, 1923, p. 2.

[26] Ibid.

[27] “The Russian Conditions Should Be Investigated According to the Facts.” Industrial Worker, September 22, 1923, p. 3.

[28] C.E. Payne, “Criticism of Russia.” Industrial Worker, November 21, 1923, p. 3.

[29]A. Lindstrom, “Appeal From Berlin.” Industrial Worker, September 9, 1923, p. 3.

[30] “Attempt to Cause Split on Old Political Issue.” Industrial Worker, September 29, 1923, p. 2.

[31] “Japanese Strike Move Blocked by Communists in Interest of Bosses.” Industrial Worker, October 3, 1923, p. 2.

[32] S.R. Darnley & C.E. Payne, “Criticism of Russia.” Industrial Worker, November 7, 1923, p. 2.

[33] John Perz, “One Who Knows Comments on Criticism of Russia.” Industrial Worker, November 7, 1923, p. 4.

[34] Chester, The Wobblies in Their Heyday (Santa Barbara, 2014), p. 220.

[35] Ibid.

[36] “The ‘News’ From San Quentin.” Industrial Worker, October 27, 1923, p. 2.

[37] “The Men Who Refused Stood for Principle.” Industrial Worker, July 25, 1923, p. 3.

[38] Chester, The Wobblies in Their Heyday (Santa Barbara, 2014), pp. 220-221.

[39] Renshaw, The Wobblies. Updated edition (Chicago, 1999), p. 260.

[40] Ibid, p. 261.

[41] Chester, The Wobblies in Their Heyday (Santa Barbara, 2014), pp. 220-221.

[42] Renshaw, The Wobblies. Updated edition (Chicago, 1999), p. 261.

[43] Dubofsky, We Shall Be All (Chicago, 1969), p. 265.

[44] Renshaw, The Wobblies. Updated edition (Chicago, 1999), p. 261.

[45] Dubofsky, We Shall Be All (Chicago, 1969), p. 265.

[46] Chester, The Wobblies in Their Heyday (Santa Barbara, 2014), p. 223.

[47] Gambs, The Decline of the I.W.W. (New York, 1932), pp. 116-117