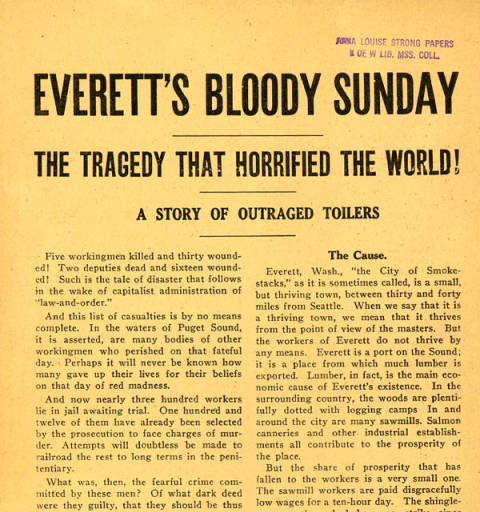

Pamphlet by Everett Defense Committee, November 1916 (University of Washington Labor Archives and Digital Collection)

Pamphlet by Everett Defense Committee, November 1916 (University of Washington Labor Archives and Digital Collection)

On November 5, 2011, a small group of Occupy Everett protesters marched silently through the city of Everett in honor of the victims of the Everett massacre. Reaching the Everett dock, the leader told the story of the 1916 "armed confrontation between local authorities, and the Industrial Workers of the World.” Narrating the bloody events that had occurred on that spot almost a century earlier, he stated, “today we reap the benefits of the blood that was spilled…but those benefits are under attack,” adding that “ninety-five years ago those voices were silenced, but we will not be silenced today.” This was followed by a chant of “we will not be silenced.”[1]

The members of the Occupy Everett movement were not alone in casting the story of the Everett massacre in a way that helped their cause. Much has been written about the massacre and trial. This report goes beyond the events to think about their legacy, about how the memory and history of those events were produced. In the months following the clash at the Everett docks another clash unfolded as many different groups and interests fought to establish what happened and who was to blame. This was a battle to control the "story" and ultimately shape the history of the Everett massacre as it would be understood by later generations. This report uses the telling of the massacre by various groups to raise broader questions about how memory is produced and the lengths to which people will go to have their views elevated to the status of history in order to further their own cause. Winston Churchill said, "history is always written by the victors,” but this report shows that history can be written by those who “will not be silenced.”

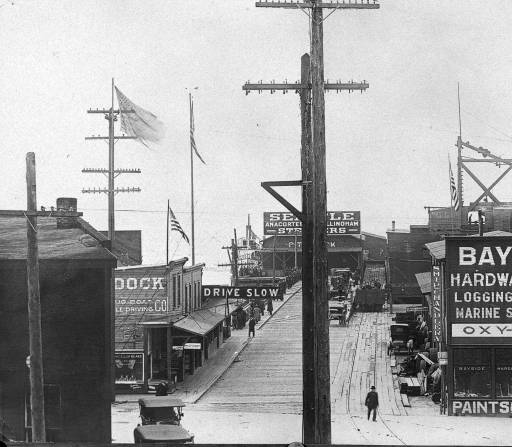

This is the Everett wharf where the Verona attempted to tie up and where gunfire took the lives of at least seven men (Courtesy Everett Public Library, Everett Massacre Collection)

This is the Everett wharf where the Verona attempted to tie up and where gunfire took the lives of at least seven men (Courtesy Everett Public Library, Everett Massacre Collection)

The city of Everett was built during a time of rapid railroad expansion and controlled from an early period by lumber barons. It was one of the new industrial cities that dotted the state. With an economy based on shingle and lumber mills, the residents described it as a “city of smokestacks.” Historian Norman H. Clark called it Mill Town in his 1970 book of that title.[5] Industrialists capitalized on this new frontier economy, leaving little for workers except low wages and harsh working conditions. Eventually, workers banded together, formed unions, and fought for better conditions. One of the unions based in Everett was the International Shingle Weavers’ Union of America, representing skilled workers in the shingle mills. The shingle weavers, who produced the cedar shingles popular as roofing and home siding materials, worked with machines that had no safety guards and were easily recognized by their missing fingers.[6]

During the recession of 1913 and 1914, wages were lowered with a promise by mill owners to raise them once the economy recovered. When the Everett mill owners refused, the shingle weavers organized and in May 1916 went on strike. The strike was fiercely resisted by mill owners who managed to operate some of the mills without the union. As the strike dragged on through the summer and into the fall, the IWW became involved despite concerns by the shingle weavers union which as an afilliate of the rival American Federation of Labor.[7]

Several of the images for this article come from the remarkable digital collection made available by the Everett Public Library. Click above to visit the collection.

The Industrial Workers of the World viewed the shingle weavers strike as an opportunity to increase membership. The IWW’s idealism, however, went beyond the fight for wages, working conditions, and better hours. The I.W.W viewed the labor fight as a class struggle. The preamble of the IWW’s constitution states, “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common,” and “there can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.”[8] The battle for the IWW was waged against a system they believed reduced men to wage slavery.

The IWW in the Pacific Northwest was made up of timber-workers, migratory workers, and hobos that rode the rails between jobs, following work.[9] In Everett the membership of the IWW employed a free speech strategy for which they were notorious. They would send soapbox orators to the streets to address working conditions, low-wages, and promote the union. City leaders, not wanting the radicals around, would pass ordinances against street speaking and arrest the men. The IWW strategy was to fill up the jails and courts, overwhelming the resources of towns. As quickly as one person was arrested, another took his place. This strategy cost the city of Spokane thousands of dollars in 1910, and after a long fight, city leaders gave into the union’s demands for fair treatment from employment agencies.[10] When the call came for a new fight in Everett, “footloose” members began to pour into the area.[11]The industrialists in Everett were determined not to let this vagabond group of crusaders into their town.

The steam vessel Verona at the Everett wharf where the gun battle occured 1917. When this photo was taken the ship was reenacting the massacre scene for members of the jury during the Tom Tracy trial. (Courtesy Everett Public Library, Everett Massacre Collection)

The steam vessel Verona at the Everett wharf where the gun battle occured 1917. When this photo was taken the ship was reenacting the massacre scene for members of the jury during the Tom Tracy trial. (Courtesy Everett Public Library, Everett Massacre Collection)

In reaction to the IWW’s entry into Everett, the city’s businessmen, who were also members of the Everett Commercial Club, sought the assistance of Snohomish County Sherriff Donald McRae. McRae deputized many of the Commercial Club members, creating a new army of citizen deputies, and the city passed a new ordinance restricting free speech. On October 30, McRae and his citizen deputies arrested, beat, and continually abused IWW members, also known as Wobblies. They forced 40 protestors to walk a railroad gauntlet of axe handles, billy-clubs and other weapons, leaving a trail of blood, teeth, and flesh on the tracks.[12] In response to this incident, the IWW called for men to join the Everett crusade. In Seattle, 20 miles to the south, the organization chartered two steam vessels, the Verona and Calista, and perhaps 300 Wobblies boarded the vessels on the morning of November 5 heading for the Everett protest.[13]

Rumors of the IWW plans reached Everett. Sheriff McRae and his deputies, armed with rifles and handguns, lined the dock and warehouses determined to stop the IWW landing. [14] As the Verona approached, McRae stood on the dock and shouted, who’s your leader?” the answer came back, “we are all leaders!” McRae said, “you can’t land here!’ again a reply, “the hell we can’t.” Within minutes there was an exchange of gunfire, leaving five Wobblies and two citizen deputies dead, and many more men wounded.

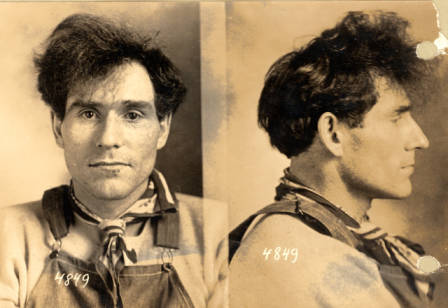

The Wobblies along with their wounded were forced to return to Seattle where 294 men were arrested and detained in the King County jail. Ultimately most were set free, but seventy-four men were sent to Everett, imprisoned, and ordered to stand trial for murder. The first and only one to be tried was Thomas Tracy. The trial was moved to Seattle because the Governor believed it would be impossible for any Wobbly to receive a fair trial in Snohomish County.[15]

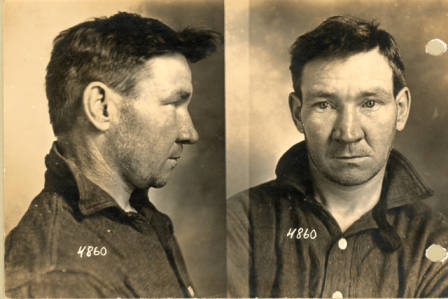

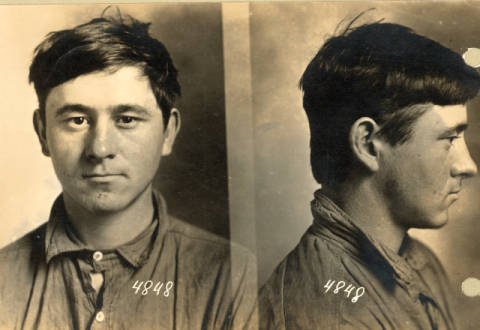

Tom Tracy was the only one of the 294 arrested IWWs who stood trial. This mug shot was taken immediately after his arrest (Courtesy Everett Public Library, Everett Massacre Collection)

Tom Tracy was the only one of the 294 arrested IWWs who stood trial. This mug shot was taken immediately after his arrest (Courtesy Everett Public Library, Everett Massacre Collection)

The Everett Massacre and the Thomas Tracy trial became a tool to advance a number of competing agendas for the IWW, for Everett city officials and business leaders, and for many local and labor newspapers. The trial also received national coverage. Each entity had an interest in the story of the Everett Massacre, whether to further their cause, silence dissent, or to sell newspapers. The IWW sought to use the tragedy as a way to increase membership, promote their cause, and create a lasting legacy of martyrdom. The city of Everett wanted to justify the actions of their officials and commercial elite and return life to normal. Historian Norman Clark describes Everett as a city on the brink of a “civil war.”[16] While many in the town sympathized with the IWW, local labor and conservative papers all had an interest in spinning the story in particular ways. The shingle-weavers union, which had been on strike for six month, now returned to work, with little or no coverage from the media. The Thomas Tracy trial then became a spectacle for the country and the focus of the media’s attention. Thus the I.W. W., the media, and the city of Everett struggled to control the telling of the story of the massacre so that the details supported particular political and ideological goals.We start by examining how the commercial and labor newspapers of Everett and Seattle shaped the story following the confrontation.

Page 1 of Everett Daily Herald, November 6, 1916

Page 1 of Everett Daily Herald, November 6, 1916

The Daily Herald was a conservative Republican and pro-business paper that served Everett readers. A considerable amount of the advertising in the paper came from the local open-shop businesses and members of the commercial club. In the days prior to the massacre the Herald ran scary stories about the Wobblies taking control of other cities. During the same period, the Herald had remained silent regarding reports of suspected abuse or wrong doing by the Sheriff and the commercial club vigilantes. The paper also failed to report the affair in Beverley Park when 40 Wobbly’s had been forced to run a gauntlet of clubs, axe-handles, and gun butts. This silence was made painfully obvious after local community leaders investigated the scene; spoke out against the violence, and news of the abuse spread through much of the town.

On the day after the massacre, the Daily Herald ran stories about the bloodshed and destruction the Wobblies had brought to the city. Two bold headlines on the front page of the paper read, “Seven Killed in IWW Battle” and “Two Everett Men, Five IWW Dead; Fifty Wounded.”[17] A list of the Everett dead and wounded was centered on the front page between other stories.[18] It mentioned those in critical condition and included a detailed list of gunshot wounds to the heart, chest, or backs of the victims.[19] The list also described where the men were employed in the community. For example the article mentioned Neil Jamison owner of the Jamison Mill, who had been shot in the finger, and Athol Gorrell, a visiting University student who had been shot in the back.[20] By depicting how the victims were tied to the Everett community, the message was that Everett’s neighbors, brothers, husbands, and sons had been attacked.

The paper portrayed the sheriff and the deputies as defenders of the community who were gunned down by an invading army. The Herald implied that the IWW had been the aggressors and cited evidence from a Coroner’s inquest held that day at which several eyewitnesses testified that the men on the Verona had opened fire on the men on the docks.[21] According to the testimony, instead of the men on the boat turning back after being warned, “almost immediately someone from the boat fired.”[22] The shooting began before McRae or his deputies had even drawn their guns.”[23] Both the inquest itself and the coverage provided a public and legal platform that exonerated the city and its officers of any wrongdoing.

The Herald described the battle as premeditated. In a story on page two, the paper proclaimed that “at the moment …the Verona was drawing into the city dock…two men pulled the fire alarm box at Eighteenth Street and Rockefeller calling out the fire station apparatus.”[24] This was the station closest to the dock. The suggestion is and that someone had a desire to draw the city resources away from the dock and thus away from the confrontation. In one of the most harrowing Herald articles, the reporter recreated the scene of motor cars carrying wounded under the Great Northern Viaduct while a jeering crowd of IWW sympathizers “laughed at the sufferings of the wounded deputies.”[25] The paper exclaimed that, while Sheriff McCrae was being driven to the hospital, one woman shouted, “Give me a rifle while I finish…”[26] The rest of the words are unreadable in the microfilm copy of the article, but it is clear that the newspaper is claiming that she wanted to kill Sheriff Don McCrae.

The Everett Commercial Club appealed to other commercial clubs to take action against the IWW or they too might suffer the consequences. In one article, the commercial club describes how “an armed horde of several hundred” IWW “with the proclaimed purpose of overthrowing the legally constituted authorities by force,” had recently attacked the city of Everett.[27] The article served to justify the violence committed by the members of the commercial club, while allowing it to begin damage control in Washington and across the country.

After justifying the actions of the city leaders and the commercial club, the Herald seemed content to let the story of the battle pass. Just three days after the bloodiest confrontation in the city of Everett’s history, the front page of the paper was covered with election news about the local Republican Party. The local election results were a victory for Republicans and for the law and order faction that backed Sheriff McCrea and the newspaper saw this as proof that the city’s officials had acted in the best interest of the community. The story of the massacre seemed to have disappeared from front page news and received only minimal coverage and local and national elections seemed to be the perfect distraction. On November 10, The Herald reported that 42 members of the IWW were being charged with murder, reinforcing the idea that the Wobblies were at fault.[28] Then on November 14, hidden on page ten of the Herald, there was a report that more people would be facing murder charges, and that the prisoners would be transferred to Everett.[29] While mentioning the release of 128 of the Wobblies, the paper never alluded to the possibility of their innocence.

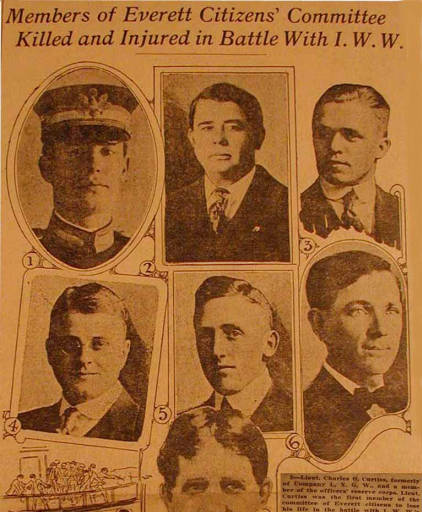

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer was slightly more even handed than the Seattle Times but in its initial coverage it sympathized only with McCrea and his hastily deputized "Everett Citizen's Committee." November 7, 1916, p.1. Courtesy University of Washington Labor Archives and Digital Collection

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer was slightly more even handed than the Seattle Times but in its initial coverage it sympathized only with McCrea and his hastily deputized "Everett Citizen's Committee." November 7, 1916, p.1. Courtesy University of Washington Labor Archives and Digital Collection

The Seattle Daily Times, was also a conservative paper, but in contrast to the Herald’s concern for the city of Everett, the Times shaped the story within the context of the national and local political climate. Times owner and publisher, Alden J. Blethen, had recently passed away, and his sons ran the paper. It was common knowledge that the Blethens viewed the IWW as anti-American and dangerous. Over the years the paper continually campaigned “against Wobblies and other political radicals.”[30] The Times often published articles attacking the union and their soapbox orations. Alden Blethen described the Wobblies as individuals who “thumbed their noses at law and order,” and “criminals who proposed to overthrow the government.”[31] During the 1913 Potlatch festival, Blethen was accused of using the Times to encourage outright violence against the Wobblies, resulting in a riot and the sacking of the IWW office in Seattle.[32] The Seattle mayor at that time, George Cotterill, condemned Blethen and became so enraged that he sent the police to close the newspaper. The Times shaped the story of the battle in Everett to further attack the IWW as lawbreakers, promote its own version of patriotism. When Seattle mayor Hiram Gill condemned the actions of Sheriff McCrea as a violation of civil liberties, the Times criticized Gill and defended the Everett authorities.

The Seattle Daily Times began telling the story of the massacre by detailing the bloodshed and its effect on the citizens of Everett. The day after the massacre, the Times ran a front page headline that exclaimed, “7 Dead 48 Wounded in Battle with IWW at Everett.”[33] The headline, combined with a description of how 2000 bullets had flown through the air, provided a sense of how much bloodshed resulted from the actions of the IWW[34] While the headline did not differentiate the IWW and Everett dead, a 1/4 page rectangular picture of Everett’s Lt. Charles O Curtis in his National Guard uniform left no doubt what side the paper was on. The picture of Curtis provided an image of a clean cut patriotic young man with a sword by his side; the type of individual who would come at a moment’s notice to defend his community.[35] The paper described Curtis’ volunteering just a day before the “riot” and leaving behind a wife and three daughters. The picture of Curtis’ body fits with theTimes projection of patriotism while also presenting actions of the IWW as anti-American. There is no mention of families of the IWW men who were killed that day.

Most of the coverage in the Times portrayed the Wobblies as the agitators. The Times reported that, according to the testimony of “L.S. Davis, a steward on the Verona,” the Wobblies fired the first shot and were responsible for a riot.[36] The Times made no mention of any of the IWW side of the story and focused on the bloodshed and the 294 rioters in the King County jail.[37] Its stories employed loaded words like "invade," "battle," and "riot" to reinforce the idea of the Wobblies’ responsibility for the violence. There were no reports of the Wobblies’ planned meeting in Everett, or information from the flyer that was distributed. However, there was a report on the front page that two hundred more Wobblies were on the way to Everett, inciting fear that the IWW was set to invade the city once again.[38] The story goes on to explain that the citizens of Everett planned to meet these invaders at the outskirts of the city to prevent them from coming in. The story of more men coming to invade, along with the violence purportedly caused by the IWW served as a defense for the actions of Sherriff McCrae and his deputies over the previous months.

When Mayor Gill of Seattle condemned the city of Everett for vigilante justice, he quickly became a focus of attack for by the Times. Gill stated “In the final analysis…it will be found that these cowards in Everett who without right or justification shot into the crowd on the boat were the murderers and not the IWW” [39] Gill went a step farther and saw to it that the jailed men had tobacco and other supplies. The next day the Times reported that the “IWW Prisoners Have Many Luxuries of Life.”[40] This portrayed the Wobblies’ jail stay as an improvement over the skid row hotels and hobo camps they were accustomed to. One officer in the jail stated, “if this kind of thing keeps on…they will have enough tobacco up there to supply the German army.”[41] Within a few days, the paper was running attack stories on Gill. One headline read, “Mayor Gill Scored for Attitude on IWW” Repudiating Gill’s account, one story reported, “Judge Burke…declaring that a magnificent example had been set by the people in Everett in defending their homes by force of arms.”[42]

The weekly Everett Labor Journal was an organ of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and a publication that “many saw…as an alternative to the daily and weekly papers which were often unsympathetic to the interest of workers.”[43] The leader of the Shingle Weavers Union, E.P. Marsh, was part owner and often served as editor. Marsh’s Shingle Weavers union was affiliated with the AFL, which disagreed with what they believed to be the radical tactics of the IWW The AFL was made up unions representing mostly skilled workers and organized on the basis of craft where the competing IWW organized unskilled and skilled on the basis of industry.[44] The IWW, accused the AFL of practicing narrow "pork chop unionism" and claimed that only the IWW could unite all workers.[45] The Journal stayed within the boundaries of the AFL philosophy of a “fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay.”

The Labor Journal presented the massacre as a story in which the IWW and the Everett Commercial Club were both unwanted, out of control, and did not have the best interest of the citizens of Everett in mind. Immediately after the massacre, Marsh ended the shingle weavers' strike. In the first issue of the Labor Journal after the massacre, the front page did not contain any headlines of the deadly fight, but rather the news that the “Shingle Weavers Vote to End Local Strike.” The Labor Journal declared that “the members of this union have the best interests of the city of Everett at heart.”[46] The Labor Journal depicted the Shingle Weavers Union as the adult in the room through the whole bloody affair. The paper describes the Shingle-Weavers as having the same views as the reputable citizens of the city, and professed that the Everett city officials and the commercial club had been continually wrong in their actions and policies.[47] For months the Labor Journal had carried a list of businesses that were pro-union, under a banner line stating that their owners were not members of the commercial club.

The Labor Journal helped the Shingle-Weavers distance themselves from the Industrial Workers of the World. The weekly proclaimed that the Shingle Weavers “have no hand in the agitation of the Industrial Workers of the World, are not responsible for them coming to this city and did not invite them here.”[48] The paper depicted the union as being the part of Everett with no blood on their hands concerning the massacre. Their affiliation with the AFL and its ideal of “a fair day’s wages for a fair days work” became evident in their view of both the IWW and the massacre. Thus the shingle weavers began its attempt to use the story of the massacre as a way to promote its sense of community, idealism, and innocence.

In contrast with the Labor Journal’s audience of the AFL members, the Northwest Worker was Everett’s Socialist newspaper. Published in Everett, Washington from 1915 to 1917,[49] the paper “served as promotional and educational instruments for the Socialist Party.”[50] According to University of Washington Labor Press Project, the circulation in October of 1915 had reached almost 7,000. Everett, at the time, boasted a population of around 30,000.[51] The paper’s editor, Henry W. Watts, was arrested before the massacre for “protesting the treatment of the IWW” by the Everett police.[52] The Socialist Party and the I.W.W had always defended labor and shared many of same ideas. Nor was it was uncommon for a person to be a member of both the SP and the IWW The closeness of their identities is clearly evidenced by the proclamation in the Northwest Worker, that “Capital is out to crush labor and that is all there is to it.”[53] Weeks before the massacre, the paper had attacked the local press for publishing false charges against the strikers and the IWW[54]

The Northwest Worker used the story of the massacre to attack capitalism and their enemies within the city of Everett. The Worker told a story that acknowledged the IWW as their own, publicly condemned the city mill owners and commercial club, and criticized the local press. Instead of calling the confrontation a “battle,” the Worker referred to it as “Bloody Sunday.” The Worker demonized capitalism by displaying the images of the Wobblies that were killed on that bloody day, and posting them on the front page of the paper. The Worker left no doubt as to who was to blame for the slaughter: the business leaders and merchants (the commercial club), whom they had described the previous month as “cockroach merchants.”[55]

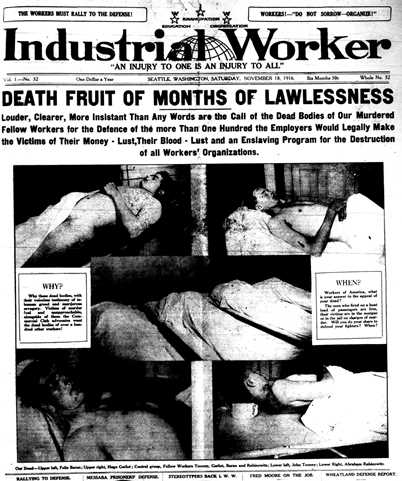

The paper’s headline on Thursday, November 25, 1916 read, “MORE OF OUR DEAD IN FIGHT FOR FREEDOM,” illustrating the paper’s usage of the Massacre to identify the dead workers with the struggle of Socialism.[56] Reinforcing the message was the description of Wobbly Abraham Robinowitz’s last words,’ “I’m dying boys, but don’t give up, I want to sing the “Red Flag” again.”[57] A series of photographs of Robinowitz and three other IWW dead, Felix Baron, Hugo Gerlot, John Tooney, covered most of the front page.[58] The photographs were more compelling than any story depicting the brutality of “Bloody Sunday,” and the lengths to which capitalists would go to keep workers from having a voice. The men’s lifeless bodies, full of bullet holes on the cold tables of a morgue, served as a message to the citizens of Everett, a reminder of what transpires when capitalist mill owners are allowed to do whatever they wish.

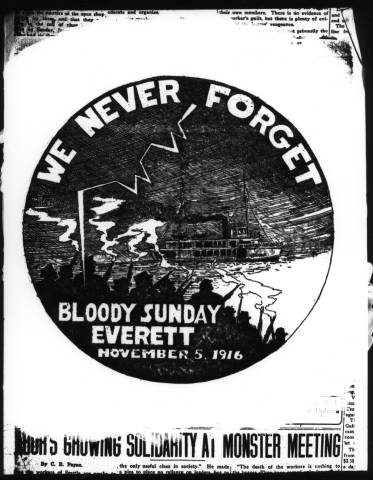

The Northwest Worker wasted no time in using the massacre to make a direct attack on their enemies by naming them individually. Under the caption “We Never Forget,” the paper listed the names of Mayor Merrill and Republican leader Ed Hawes, followed by the commercial club members involved in Bloody Sunday.[59] In another list of names, under the heading “Wage Slave Deputies,” theNorthwest Worker implicated the deputies and listed names of their regular employers.[60] The Worker also reported that attorney Fred Moore had been hired to represent the IWW defendants and published accounts of the funeral of the victims, and some of the public meetings to be held.

The Industrial Worker displayed mortuary photos of IWW victions on the front page of the November 18, 1916 issue

The Industrial Worker displayed mortuary photos of IWW victions on the front page of the November 18, 1916 issue

The Industrial Worker was one of the most important newspapers published by the IWW. Widely circulated in the western United States, the paper had been published in Spokane until 1913. It had resumed publication from its new base in Seattle in April 1916, shortly before the trouble in Everett.[61] Every issue included the preamble of the IWW constitution, reminding the reader that “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common.”[62] The Industrial Worker was similar to the Northwest Worker in its anti-capitalist views and represented Wobbly culture in the West. The paper was consistently used as a voice to call workers to labor battles around the West.

The weekly Industrial Worker was more than a paper for the Wobblies; it was a way to keep the extended family that the union represented together. While the actual union hall was a place that many Wobblies depended on as an occasional place to sleep, eat, and pick up mail, the Industrial Worker itself became sort of a union hall.[63] One way this was done was through a section called “Is your letter here” which listed mail that had been delivered to union halls across the IWW network.[64] For a man without a regular home, or little extended family, this paper instilled a sense of belonging. The paper also served as way to keep the union strong and to build it. Joining the union was as simple as sending two dollars to the paper; in return a member received a union card and a six-month subscription to the newspaper.[65] Although the circulation probably never exceeded 9,000, the Industrial Worker was able to serve community workers that may have otherwise been unreachable.[66]

In the immediate aftermath of the massacre, the Industrial Worker, like other periodicals examined thus far, actively expressed its version of the events. The paper portrayed the Wobblies as heroes and not as victims of the events. The language used to describe the battle became increasingly more memorable. The paper shaped the story to attack its political and ideological enemies, while aligning itself with other unions, creating an image of the IWW not as radicals, but as defenders of the worker and defendrs of free speech rights. Unlike the local press, the I.W.W had a clear aim to use the story as a vehicle to promote the union’s ideology.

After the massacre, the Industrial Worker’s characterization of the battle evolved. On November 11, the paper described the battle as a holocaust. By November 18, the paper spoke of the cowards and murderers who had attacked the Wobblies. In the November 25 issue, the paper adopted a term used by the Northwest Worker, “Bloody Sunday.” Eventually the Industrial Worker called the confrontation, a "massacre." This contrasts with the “battle”, and “conflict”, used in the Everett Herald or “invasion”, and “riot” spoken of in the Seattle Daily Times.[67]

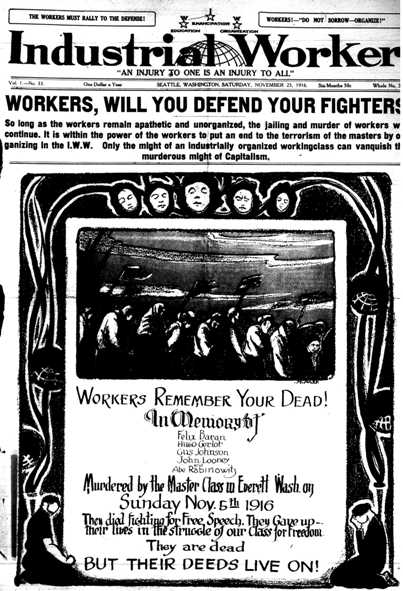

The Industrial Worker listed all of the dead in the November 25, 1916 issue

The Industrial Worker listed all of the dead in the November 25, 1916 issue

The Industrial Worker listed those who had lost their lives, defining each by their place of residence and their occupation. The paper provided equal space for the IWW casualties and the citizens of Everett. However, the class distinction was made evident. The IWW dead were listed by name and hometown.[68] Hugo Gerlot and Harry Pierce’s names were simply followed by Milwaukee. Additionally, the wounded were listed as laborers, loggers, and longshoremen.[69] Many of the IWW could immediately identify with this. Being on the road was part of the Wobbly lifestyle. The paper also listed the names of Everett dead and wounded, along with their residence and occupation. The death of Lt. Charles Curtis received the most attention; Curtis was described as an office manager of the Canyon Lumber Company, a former member of the adjunct General’s staff, as well as a member of the Washington State National Guard.[70] The paper also listed the occupations of men like Charles Tucker, a foreman at the Clough Hartley Mill, Owen Clay, a department manager at the Weyerhauser Lumber Co., and former mayor Thomas Headley.[71] Intentionally, the list demonstrated the class difference among the casualties. In the article adjacent to the lists of the dead and wounded, the paper makes its stance clear. It describes the Everett men as individuals who only pretended to be patriotic citizens, but when nighttime came they "put on masks and brutalized defenseless and homeless members of the working class.”[72]

The Seattle funeral of IWW members Baran, Gerlot, and Looney was used as a public spectacle to broadcast their sacrifice in Everett. On November 18th, an estimated 1500 people attended the ceremony.[73] The event was filled with union symbolism. The procession was followed by men marching military style, in rows of four, with red roses pinned to their chests. The procession passed through the downtown business district of Seattle, in a show of solidarity and strength in front of business owners. After reaching their final destination atop Queen Ann Hill, mourners sang the “Workers of the World,” followed by a speech by IWW organizer Charles Ashleigh. Afterwards the crowd sang, “Red Flag” and threw red roses on the graves of the martyrs.[74]

Alex Downey (top), Harold Miller, F.O. Watson, E.M. Beck, and Frank Stewart were among the 74 IWW members arrested after the Verona massacre. These other mug shots can be found at the online archives of Everett Public Library's Everett Massacre Collection

Alex Downey (top), Harold Miller, F.O. Watson, E.M. Beck, and Frank Stewart were among the 74 IWW members arrested after the Verona massacre. These other mug shots can be found at the online archives of Everett Public Library's Everett Massacre Collection

The IWW elected a defense committee to raise money for the defendants facing trial and that committee issued the Everett Defense Newsletter on a periodic basis. The Newsletter was multi-functional, serving as a press release, a tool for fundraising, and a way to keep the massacre story alive. Committee member Charles Ashleigh was placed in charge of publicity and served as editor of the Newsletter.[75] The first issue appeared on December 2, 1916. Located in the top corner of the newsletter was a plea to newspaper editors to include the Newsletter in the next edition of their paper.[76] The Newsletter also invited IWW local secretaries to post it in their union hall, thus enabling workers around the country to keep up with the latest news concerning the massacre. This not only helped the IWW control the story, but also helped workers all over the country to make it part of a wider struggle. At the end of each publication, there was a request for donations to the Defense Fund, and a plea to write to President Woodrow Wilson and Washington Governor.[77]

The IWW held a number of public meetings that drew attention to the massacre. The Defense committee sponsored mass meetings in Everett and Seattle. They also promoted other events, including dances, prize fights, and picnics to continually raise money and create opportunities to tell the IWW version of the massacre story. The meetings often used Socialist halls and had speakers from the various labor organizations and political groups. This provided a platform for the Wobblies to promote their ideology while at the same time finding common ground with other organizations. Sharing the abuses of workers in the violent action at Everett drew attention to a common cause.

On November 18, over 5,000 people crowded the Dreamland Rink in Seattle for a mass meeting to hear details of the massacre, demand an investigation, and show support for the workers.[78] The meeting included representatives of the IWW, the Central Labor Committee, the A.F. of L., and various local organizations. In a variety of ways, the speakers were able to identify with the IWW After hearing the speakers, Judge Winsor said, “I am almost afraid to hear any more accounts…I am afraid I shall become an anarchist myself.”[79] Central Labor Council leader Hulet M. Wells later described how the I.W.W and AFL may have different methods, but “We of the A.F. of L…are brothers of the working class and in the great class struggle.”[80] In Pioneer Square an “International Mass Meeting” held on December 3, featured speakers from five different nationalities, all of whom expressed their outrage against the events in Everett. The diversity of these speakers reflected on the IWW ideology that transcended to all ethnic backgrounds. Additionally, the meeting was a representation of the five martyrs who were themselves representatives of five different ethnic groups.

The Defense fund committee also called upon the services of IWW national leader Elizabeth Gurley Flynn.[81] Flynn’s ability to tell the Everett story by connecting it with the labor battles across the country became another potent tool in the IWW’s quest to shape the massacre story. Flynn was the IWW "Rebel Girl," so named in a song written by Joe Hill the martyred Wobbly song writer. The Industrial Worker described her as “the best woman labor speaker in the country” and “the Joan of Arc of labor.”[82] Flynn began as a Socialist before becoming a full-time IWW agitator, and she is an excellent example of the relationship between the two groups. She had been arrested several times, including when she was pregnant during the free speech fight in Spokane.[83]

Flynn spoke often over the next two months, traveling throughout the state and across the Columbia to Portland to tell the story and collect funds for the defense.[84] When Flynn spoke in the city of Everett, she began by stating, “We are here this afternoon to present to you the workers side of the Everett situation.”[85] Flynn compared the Everett event to violent labor struggles around the country.[86] During her talk in Everett she described the men and women killed in Bayonne N.J., the Masabbi Range in Minnesota, and Lawrence Kansas.[87] Flynn described intimately some of the tragic and bloody deaths of workers in the labor battles and compared them with those in Everett.[88] Then Flynn argued for the innocence of the jailed Wobblies and explained how the deputies had been killed by their own crossfire. After the meeting in Everett, as with all of Flynn’s meetings, a collection was taken up for the prisoners’ defense fund to pay for the legal fees of the men.[89]

With 74 men in the Everett jail facing murder chargers, a request was made to the Chicago headquarters for a defense counsel.[90] Soon, Fred Moore was on the job. Moore had represented the Wobblies in many free speech fights, including Spokane. With the endorsement of Judge Donsworth, former Seattle prosecutor George Vanderveer was brought in as associate counsel.[91] Vanderveer fit the bill as counsel for the Wobblies. He was no stranger to fisticuffs, and occasionally would seek out a good scrap in Seattle’s skid row. He had also built a reputation for his radical courtroom theatrics. Vanderveer’s wife was reluctant about his decision to take the case, due to the IWW’s radical ideals. She feared his association with them might damage his reputation. Vanderveer, however, viewed the case as an opportunity, stating that, “by the time this is over, I’ll be recognized as one of the outstanding criminal lawyers in the United States.’’[92]

Vanderveer recognized that the trial would be a spectacle for the entire nation. The I.W.W had something that many times keeps causes alive in the press, martyrs suffering in jail. Their incarceration was one reason the union had an opportunity to re-tell the story of the massacre many times over. Up until the trial, the Industrial Worker, and the Defense Fund Newsletter continually ran stories describing the prisoner’s abuse, and the necessity to move the trial to a place where the men might have a chance for a fair trial, Seattle. The struggle to control the massacre story would now move into the courtroom. The first man to stand trial would be Thomas Tracy.

The Thomas Tracy trial began March 5, 1917, four months after the incident. Excitement swelled inside the courtroom as reporters representing newspapers and magazines from around the country came to witness the spectacle.[93] Throughout the trial the commercial press around the country reported many of the I.W.W arguments from the trial, as the local press continued its coverage. [94] A headline in the Everett Daily Herald stated simply the “Trial of Tracey Gets Under Way.”[95] In contrast, the Industrial Worker proclaimed that “Labor History’s Greatest Trial” had begun.[96] The newspapers would continue to report the massacre story, and who fired the first shot was a constant question. Thomas Tracy, now clean shaven and wearing a suit, looked more like a conservative business-man than the rough IWW worker in his mug shot photo.[97] In the midst of a battling press, it quickly became clear that the Thomas Tracy trial was about more than innocence or guilt.

To control the story in the courtroom required controlling the press coverage. The city of Everett for example, continually justified their actions. In the backdrop of America preparing for a possible entry into WWI, the city underscored the IWW’s revolutionary ideals, and the events surrounding the massacre seemed to become less about murder and more about patriotism. Both the IWW and the city of Everett understood the power of the press and both hoped to use the courtroom drama to frame the events of the massacre to fit their political agenda. The conservative press and the city of Everett desired to expose the IWW as being focused on ideas of sabotage, anti-capitalism, and the promotion of a new political system. The IWW sought to use the press coverage of the trial to promote the ideals of the union, to expose the evils of capitalism and the inequalities it created. Understanding the political war that was about to be waged, Judge Roland opened the trial, by reiterating to all parties that the case was about murder.[98]

Snohomish County used a team of prosecuting attorneys. Serving as Chief Prosecutor was a very youthful Lloyd Black.[99] Reinforcing Black was assistant prosecutor H.D. Cooley, an Everett attorney, and a member of the commercial club. Another assistant prosecutor, A.L. Vietch from Los Angeles brought experience to the team.[100] Because of his presence on the dock at the massacre, Cooley’s association with the Everett Commercial Club was repeatedly attacked by assistant defense council George Vanderveer during the trial.

The ongoing struggle to control the story in the press was clearly illustrated during jury selection. Potential jurors were asked whether or not they read labor or Socialist newspapers.”[101] Political enemies did not escape the fray. One juror was asked if they had read a statement by Seattle Mayor Hiram Gill regarding the shooting at Everett.”[102] Another was even questioned about Anna Louise Strong, a local Seattle activist, who had been asked to write about the trial for the New York Post. However, no one was asked if they read the local commercial press publications.

The prosecution presented its case first, describing the IWW and its members as a band of vagabonds and revolutionaries. Prosecutor Black’s opening was reported in detail by the Everett Herald. Black began by explaining how the I.W.W desired social revolution, saying “The IWW was not like the Socialists who sought change through the legal means of political involvement and the ballot.” [103] Black also argued that the I.W.W did not seek to negotiate for fair pay and working conditions as the trade unions [104] The IWW, the prosecution argued, desired “social revolution” and believed in using violence and sabotage to accomplish their goals.[105]

After winning a ruling from Superior Judge Roland, the prosecution introduced a selection of IWW literature to the jury.[107] H.D Cooley presentedarticles from the Industrial Worker[108] Black read pieces of Sabotage Its History Philosophy and Function, by Walker C. Smith to reinforce the idea that the destruction of property was part of IWW philosophy.[109] Smith had called, “Sabotage…a mighty force as a revolutionary tactic against the repressive forces of capitalism”[110] The Everett Daily Herald pointed out the fact that Walker Smith and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, who had also written on sabotage, were present in the courtroom.[111]

The testimony of Everett Mayor D.D. Merrill was used to corroborate accusations of radicalism and reported in detail by the Everett Herald and disputed by the Industrial Worker. Merrill testified that a warning had been sent prior to the massacre by “delegations claiming to represent the I.W.W” that there would be retaliation if members were not allowed to speak.”[112] Merrill then detailed how mysterious fires had broken out at a various mills in town.”[113] He insinuated that the fires were acts of sabotage committed by Wobblies. The Industrial Worker claimed that Merrill's testimony backfired and that he was “a good witness for the defense” because he repeatedly answered defense attorney Moore’s questions with “No, I don’t know, I don’t think so, and I don’t remember.”[114] Insinuating his memory lapse of details was evidence that he had something to hide; the Industrial Worker headlined its coverage of Merrill’s testimony “Witnesses Having Struggle With the Truth.”[115] Assistant prosecutor A.L. Vietch plainly detailed what the story of the massacre meant to the state. Vietch proclaimed “the killing…gave the state its case, but conspiracy might be found to spread over the entire nation”[116]Vietch’s statement is an example of the determination of the prosecution to amplify the dangers of the IWW across the nation by suggesting Everett is not their last stop. The prosecution entered evidence of telegrams the IWW had used in a call for men to come to Everett. Merrill’s testimony cited an Industrial Worker article calling for 2000 men to lay siege to Everett.[117]

After the prosecution finished, Thomas Tracy seemed content to let the jury decide his fate.[118] Tracy told his counsel, “as far as I’m concerned, you could let this case go to jury right now.”[119] The defense had been eagerly awaiting their moment to depict what they considered a great social injustice and further the cause of the IWW in the media.

The defense began to argue its case on April 2, 1917, the same day President Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany. The nation’s impending entrance into the war came to dominate the headlines of the commercial press. Yet, this did not stop the struggle to define the events of November 5, 1916. Chief Counsel for the defense, attorney Fred Moore, had experienced trials like this before. He was well acquainted with the prosecutor’s strategy of attacking the IWW To combat this, the defense would tone down their rhetoric and promote an image of a union whose sole purpose was the betterment of people everywhere. The tone was evident everytime one looked over at Thomas Tracy sitting in the defendant’s chair, clean cut, well shaven, and wearing a Sunday suit.

Over the course of the trial, the defense also called upon a great number of witnesses to illustrate the brutality and vigilante justice that had occurred in Everett. By doing this, in contrast to the constraint of the IWW, the citizen deputies and Sheriff were shown as the aggressors. Prior to the massacre, the Industrial Worker had reported the actions by the deputies as “an almost unbelievable barbarity.”[120] The defense called a number of witnesses that reminded the jury of the gauntlet the men had been forced to run at Beverly Park. Their goal was to present an image of Everett as a city controlled by business and money. The testimony that defined the I.W.W’s philosophy and vision came from the first two witnesses, Herbert Mahler and James P. Thompson.

As the defense’s first witness, Herbert Mahler began to defend the I.W.W literature and principles. Upon cross examination, Mahler was asked about sabotage. He explained that, if a person did not have access to justice or a way to retaliate, it would be acceptable to destroy equipment or property.[121] The next witness, James P. Thompson, gave dramatic testimony that represented the Wobblies as noble men. Thompson explained that trade unions did not have the solidarity of the IWW and little desire to engage in honest discourse. When strikes were called, many “times workers were pitted against each other” and union scabs would be sent in.[122] In contrast to the trade unions, the I.W.W, believed in complete solidarity. With solidarity, Thompson described how the working class could shut down the means of production, a power only they had.[123]

Thompson made the plan of the IWW to build a better society comprehensible to a wider audience. Their goal was to eliminate capitalism, the wage system, and property ownership.[124] This new society would have collective property, and industry would operate on a co-operative plan.[125] The goal was ultimate equality. No child born into this world would be born with more or less than anyone else. According to Thompson, the child would have an equal share of the earth.[126] Thompson made his point in the context of Constitutional ideals, claiming that this new society would provide a way for everyone to be born truly free and equal.[127] Deflecting the idea of the IWW as revolutionaries, Thompson described them as a “new society from the old.”[128]

Refracting the idea of the I.W.W as un-patriotic, Thompson defined the union’s world view as one of inclusion. Describing nationalism and patriotism as the values used to justify war, Thompson proposed that in the big picture there are no foreigners.[129] In the environment of President Wilson’s petition to Congress for a Declaration of War, Thompson argued that the IWW goal of equality was not anti-American but pro-human. On May 1, as the trial continued, the IWW held a May Day Parade. This time an American flag was proudly displayed.

In closing, Fred Moore reiterated to the jury that their verdict would be wired all over the world.[130] Their decision would impact all labor, whether organized or unorganized.[131] Moore made clear that the verdict in the courtroom would be the verdict in the media. As he told the jury, who would win the struggle over the story of the massacre was now in their hands. It took 22 ballots before jury would hand down a verdict.[132] The verdict came back not guilty, “based on the probability that Beard and Curtis were killed …by friendly fire.”[133] The victory was celebrated as a first for the labor struggle in the Northwest.[134] The next day the papers reported the verdict and details from the trial.

The Seattle Daily Times reported the verdict on May 5, 1917. The headline simply read, “Jury Finds Tracy Not Guilty After Long IWW Trial.”[135] The article was buried amongst headlines and stories of the war in Europe. The Times reported that Judge Roland had sternly warned the IWW sympathizers present not to cause a disturbance anywhere near the court, or action would be taken. In an attempt to depict Seattle’s fairness but still not present the IWW as being guilty, the Times detailed Roland telling Defense Counsel Moore to “counsel his people not to attempt to repeat what happened in Everett…you are human beings, and so are the people of Everett do not go up there an jeer or shake the red flag or sure as fate something will happen again”[136]

Atop the front page of the May 5th Everett Daily Herald was a headline reading, “IWW Defendant Acquitted Today.” The paper followed with a quarter page story entitled, “Tracy Set Free by Seattle Jury.” The article contained a brief synopsis of the events leading up to the massacre and detailed the IWW’s violation of Everett ordinances. While distancing itself, the newspaper's goal seems to be to make peace. The paper went on to report that, over the course of the trial, many Everett citizens had testified to the peaceful nature of the Wobblies. The article mentioned the estimated cost to the city and the fact that many witnesses identified Thomas as a shooter from the Verona. The story mentioned that 60 prisoners were to be released, and that that the strongest case the prosecution had was against Tracy. The tone of the article appears to portray an attempt by city to acknowledge both sides and begin to put some closure on the event. By the next day, the trial disappeared from the front page and the Herald like the Seattle Daily Times began to focus on the war.

After the not guilty verdict, the May 11, 1917 issue of the Labor Journal carried a one paragraph story hidden on page three. Detailing the choice the state was left with after the verdict, the headline simply stated, “Proceed with Trial or Release Prisoners” The Labor Journal had dedicated almost no coverage to the Thomas Tracy Trial, and the depiction of the verdict illustrates a determination by the paper to give no credit or coverage to the IWW The paper’s idea of controlling the story of the massacre seemed to be the idea that there wasn’t one.

The Northwest Worker claimed the not guilty verdict was a great victory for the Socialist Party. The May 17, 1917 issue of the Northwest Worker carried the headline "Tracy Verdict.”[137] The article claimed that from the start, Socialists were in the thick of the fight alongside the Wobblies. While claiming victory, the paper reminded its readers of the harassment and persecution they suffered from the mill owners and the commercial club. It also detailed how the Socialists would have held more meetings but did not want to detract from the IWW’s program.

The Industrial Worker’s May 12th headline proclaimed “Verdict Guilty Against Everett Bosses.”[138]The Industrial Worker detailed much of the closing arguments by both sides. The IWW weekly proclaimed victory but also a determination to keep the fight going. According to the paper, the verdict clarified divisions along class lines. The newspaper noted Prosecuting Attorney Black’s closing statement when he described the citizens of Everett as professionals, family men, and people of good character while describing Wobblies as men with no home, no friends, and with no community.[139] The Industrial Worker left the battle lines clearly drawn. In contrast to the commercial medial, the local labor papers, and the city of Everett, the IWW was determined not to let the story die.

The victory in the courtrooms was not only evident in the silencing of the commercial press regarding the massacre; it became a rallying call and organizational tool. Spending over $37,000 dollars on Tracy’s defense proved the IWW’s determination and loyalty to its cause.[141] The win gave the IWW legitimacy and attested to the legality of their organizing techniques.[142] The 74 men that were released from jail became job delegates and took the story on their campaign for the union.[143] George Vanderveer remarked that the more the IWW men “got kicked around the larger they grew.”[144]The Seattle office, which had only had two on staff at the beginning of the Everett campaign, employed thirty within a couple months after the verdict.[145] And 1917 would witness the IWW's great campaign to organize the timber industry. [146]

Industrial Worker January 27, 1917. Courtesy Everett Public Library's Everett Massacre Collection

Industrial Worker January 27, 1917. Courtesy Everett Public Library's Everett Massacre Collection

The story of the Everett Massacre has been pushed and pulled in many directions. The local and labor newspapers, each with their own political, social, and financial agendas, told the story in different ways. But the IWW’s determination to produce press releases, posters, postcards and other literature ensured that their version of the massacre would not be silenced. The various public events, including the spectacle of the martyrs’ funeral procession, serve as examples of the IWW’s determination to use the story of the massacre to promote their cause. A graphic that appeared in the January 27, 1917 issue of the Industrial Worker made the point: "We Never Forget."

And the IWW effort to control the story would not end. Within a year, the Everett Massacre, by Walker C. Smith was published by the Industrial Workers of the World. It was the first detailed account of the events leading up to the Everett Massacre and the ensuing trial of Thomas Tracy and Smith's account has had a lasting impact. For one thing, it includes the closest thing to transcripts of the trial testimony. The official transcripts disappeared at some point after the trial. Vividly written, with a powerful argument that shows the Wobblies as martyrs, the book is an example of the union’s relentless use of the massacre as a rallying cry for workers.

During the red scare and the McCarthyism of the 1950’s, two new books carried on the story: The Rebel Girl, an autobiography of IWW activist Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and Counsel for the Damned a biography of George F. Vanderveer. Both contained an account of the massacre story. At the time, many US citizens were being targeted and blacklisted for political beliefs considered anti-American. Many IWW members had suffered a similar persecution during WWI. Both books describe Flynn’s and Vanderveer’s involvement in the IWW and the trial of Thomas Tracy as a victory for the IWW

In the 1960s and subsequent decades, the story would be renewed by activists and scholars sympathetic to the social movements of a new generation. In 1967, historian Robert Tyler published Rebels in the Woods; the IWW in the Pacific Northwest, including a key chapter on Everett. Norman Clark's Mill Town: A Social History of Everett, Washington, from its Earliest Beginnings on the Shores of Puget Sound to the Tragic and Infamous Event Known as the Everett Massacre, following in 1970. Numerous articles in magazines and academic journals added to the interest, and the incident was explored in the 1979 documentary film, Wobblies. Almost all of these accounts follow the basics of the IWW interpretation. More recently, websites, including the wonderful digital archives made available online by the Everett Public Library and the University of Washington's Labor Archives, tell the massacre story[147] And social movements have found the story useful as we saw in the opening vignette about the Occupy Everett marchers in 2011. The fact that the I.W.W‘s version of the events of November 5, 1916 lives on suggests that many times history is not told by the victor, it is sometimes told by those who refuse to be silenced.

[1] “Everett Massacre March.wmv” [video]. (2011). Retrieved November 24, 2011, from http://youtu.be/06B7CIRtxY8

[5] “The Everett Massacre” The Everett Public Library, http://www.epls.org/nw/dig_emassacre.asp (accessed, November, 22 2011)

[6] Norman H. Clark, Mill Town: A Social History of Everett, Washington, from its Earliest Beginnings on the Shores of Puget Sound to the Tragic and Infamous Event Known as the Everett Massacre (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1970), 92

[7] Clark, 173

[8] IWW Constitution

[9] Robert Tyler, Rebels in the Woods: The IWW in the Pacific Northwest, (Eugene: University of Oregon Press, 1967), 26

[10] Tyler, 39

[11] Clark, 200 “footloose”

[12] Clark, 195-98

[13] Clark, 200

[14] Tyler, 74

[15] Elizabeth Hurley Flynn, Rebel Girl : An Autobiography My First Life (1906-1926)(New York, International Publishers, 1955), 224

[16] Clark, 223

[17] “Seven Killed in IWW & Two Everett Men, Five IWW Dead; Fifty Wounded.”, Everett Daily Herald, Nov., 6, 1916

[18] Ibid

[19] Ibid

[20] Ibid

[21] “First Shots Came from Boat Witness’s at Inquest Declare.” Everett Daily Herald, Nov. 6, 1916

[22] Ibid

[23] “Men on the Steamer Opened Fire on the Dock First”, “Everett Daily Herald, Nov. 6, 1916

[24] “Fake Fire Alarm Turned in as Verona Docks”, Everett Daily Herald, Nov. 6, 1916

[25] “Two Everett Men, Five IWW dead; Fifty Wounded”, Everett Daily Herald, November 6, 1916

[26] Ibid

[27] Ibid

[28] “41 IWW Being Placed Under Murder Charge,”, Everett Daily Herald, Nov. 10, 1916

[29] “Murder Charge is Made Against More of the Verona Crowd”, Everett Daily Herald, Nov. 14, 1916

[30] Sharon, Boswell, Raise Hell and Sell Newspapers: Alden J. Blethen and the Seattle Times, (Pullman: Washington State University Press), 1994

[31] Boswell, 216,18

[32] Boswell, 216

[33] “7 Dead 48 Wounded in Battle with IWW at Everett” Seattle Daily Times, Nov. 6 1916

[34] Ibid

[35] “National Guard Reserve Officer Killed in Riot”, Seattle Daily Times, Nov. 6 1916

[36] “Seven Dead After Bloody Battle at Everett”, Seattle Daily Times, Nov. 6 1916

[37] “Twelve More May Die From Wounds-Seattle and King County Jail Holds 295 Rioters”, Seattle Daily Times, Nov. 6 1916

[38] “Bullets Fly Like Hail in Fierce Fight”, Seattle Daily Times, Nov. 6,1916

[39] “Mayor Gill Says IWW Did Not Start Riot”, Seattle Daily Times Nov. 8, 1916

[40] “IWW Prisoners Have Many Luxuries of Life. “ Seattle Daily Times, Nov. 9, 1916

[41] Ibid

[42] “IWW Stand of Executive Brings Action”, Seattle Daily Times, Nov. 15, 1916

[43] Library of Congress

[44] The American Federation of Labor .US History.org http://www.ushistory.org/us/37d.asp (accessed 6/1/2012)

[45] Ibid

[46] “Shingle Weavers Vote to End Local Strike”, Labor Journal, Nov. 10, 1916

[47] Ibid

[48] Ibid

[49] “Northwest Worker.” Labor Press Project Pacific Northwest. http://depts.washington.edu/labhist/laborpress/NWWorker.shtml (accessed Dec. 1, 2011).

[50] “About the Northwest Worker.” Library of Congress. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88085770/.(accessed Dec. 1, 2011).

[51] Ibid

[52] “Northwest Worker.” Labor Press Project Pacific Northwest. http://depts.washington.edu/labhist/laborpress/NWWorker.shtml (accessed Dec. 1, 2011).

[53] “The Class Struggle”, Northwest Worker. Sept. 28, 1916

[54] Ibid

[55] “Mob of Everett Merchants and Mill Owners Run Amuck in the City”, Northwest Worker, Sept. 14, 1916

[56] “MORE OF OUR DEAD IN FIGHT FOR FREEDOM.” Northwest Worker. Nov. 25, 1916

[57] Ibid

[58] Ibid

[59] “We Never Forget”, Northwest Worker, Nov. 23, 1916 pg.4

[60] “Wage Slave Deputies”, Northwest Worker, Nov. 23, 1916 pg.4

[61] James R. Foreit, “The Industrial Worker in the northwest, 1909-1931; a study of community-newspaper interaction” (M.A. Thessis, University of Washington, 1969). 94

[62] Industrial Worker, Nov. 11, 1916

[63] Foreit, 11

[64] Foreit, 14

[65] Foreit, 108

[66] Kenyon Zimmer, "IWW Newspapers 1906-1946 (maps). IWW History Project http://depts.washington.edu/iww/map_newspapers.shtml

[67] Two Everett Men, Five I.WW Dead; Fifty Wounded” Nov 6; “Men on the Steamer Opened Fire on the Dock” Everett Daily Herald, Nov 6. 1916 “National Guard Officer Killed in IWW Riot At Everett”, Seattle Daily Times Nov. 6, 1916.

[68] Open Shop Advocates Take Death Toll”, Industrial Worker, Nov. 11, 1916

[69] Open Shop Advocates Take Death Toll”, Industrial Worker, Nov. 11, 1916

[70] ibid

[71] Ibid

[72] Ibid

[73] “The Funeral”, Industrial Worker, Nov. 18, 1916

[74] Ibid

[75] “Defense Committee Elected” Industrial Worker, Nov. 25, 1916

[76] Everett Defense Fund Newsletter, Dec. 2, 1916

[77] Everett Defense Fund Newsletter, Dec. 2, 1916

[78] “Five Thousand Demand Investigation of the Everett Crime”, Industrial Worker, Nov. 25, 1916

[79] Ibid

[80] Ibid

[81] FLYNN,220

[82] Industrial Worker, Jan. 20, 1917

[83] Industrial Worker, Jan. 20, 1917

[84] “Gurley Flynn Dates” Industrial Worker, Jan. 27, 1917

[85] Flynn, 224

[86] Ibid

[87] Ibid

[88] Flynn, 224

[89] Flynn, 224

[90] Hawley, Lowell S. and Potts, Ralph Bushnell. Counsel for the Damned (New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1953) 189

[91] Ibid

[92] Hawley, 191

[93] Walker C. Smith “The Everett Massacre” (Chicago: I.W.W Publishing Bureau, 1916) 143

[94] Hawley, 200

[95] “Trial of Tracey Gets Under Way Today” Everett Daily Herald, March 5, 1917

[96] “Labor History’s Greatest Trial Opens” Industrial Worker, March 5, 1917

[97] “Picking the Jury for the IWW Trial Moves Rapidly” Seattle Daily Times, March 5, 1917

[98] Ibid

[99] Smith, 143

[100] “Class Struggle Evident in Trial” Industrial Worker, March 10, 1917

[101] “Picking the Jury for the IWW Trial Moves Rapidly” Seattle Daily Times, March 5, 1917

[102] Ibid

[103] ”Black Opening Trial, Assails IWW Claims” Everett Daily Herald, March 9, 1917

[104] Ibid

[105] ”Black Opening Trial, Assails IWW Claims” Everett Daily Herald, March 9, 1917

[106] Ibid

[107] “Merrill Tells of Warning Given by I.W.W Delegation” Everett Daily Herald, 3/16/1917

[108] Ibid

[109] Ibid

[110] Walker C. Smith, Sabotage: Its History, Philosophy & Function,(written 1913, this edition ca. 1917) “IWW Pamphlets and other Literature” http://www.workerseducation.org/crutch/pamphlets/pamphletstitle.html (accessed May, 5, 2012).

[111] ”Black Opening Trial, Assails IWW Claims” Everett Daily Herald, March 3, 1917

[112] Merrill tell of Warning Given by I.W.W Delegation” Everett Daily Herald, 3/16/1917

[113] Ibid

[114] “Witnesses Having Struggle With the Truth” Industrial Worker, March 24, 1917

[115] Ibid

[116] Ibid

[117] “Merrill tell of Warning Given by I.W.W Delegation” Everett Daily Herald, March 16, 1917

[118] Hawley, 200

[119] Ibid

[120] “Story of Savagery Graphically Developed”, Industrial Worker, March 21, 1917

[121] Smith, 178

[122] Smith, 179

[123] Ibid

[124] Ibid

[125] Ibid

[126] Ibid

[127] Smith, 183

[128] Ibid

[129] Ibid

[130] Hawley,208

[131] Ibid

[132] “Jury Finds Tracy Not Guilty After Long IWW Trial.” Everett Daily Herald May 5, 1917

[133] Clark, 212

[134] Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 4: The Industrial Workers of the World, 1905-1917. (New York: International Publishers 1965) 546

[135] “Jury Finds Tracy Not Guilty After Long IWW Trial.” Seattle Daily Times May 5, 1917

[136] Ibid

[137] “Tracy Verdict.” Northwest Worker, May 17, 1917

[138] “Verdict Guilty Against Everett Bosses.” Industrial Worker, May 5, 1917

[139] Ibid

[140] Ibid

[141] Hawley, 210

[142] Foner, 546

[143] Foner, 547

[144] Hawley, 214

[145] Foner, 547

[146] Clark, 217

[147] “The Everett Massacre” The Everett Public Library, http://www.epls.org/nw/dig_emassacre.asp (accessed, Nov. 22, 2011)