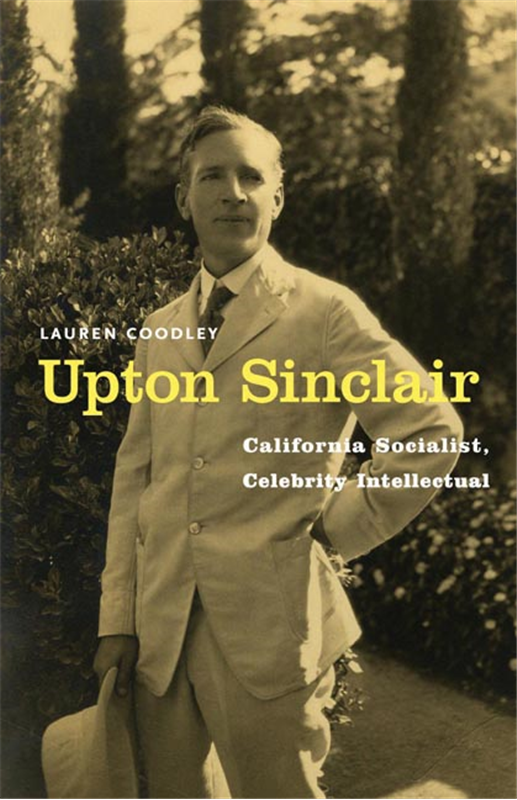

(University of Nebraska Press, 2013)

(University of Nebraska Press, 2013)

The strike of militant longshoremen, sailors and oil workers in the Los Angeles harbor at San Pedro is part of the forgotten history of California.[1] In “Pedro,” as in Ludlow, Upton Sinclair would place himself directly into a labor struggle. Many writers were sympathetic to the struggles of organized labor in California, but few put themselves in harm’s way, as Sinclair did at Liberty Hill.

The IWW had long been active in San Pedro, holding its first meeting in the port city only four months after its founding convention in 1905. Later, Wobbly composer Joe Hill’s IWW card was issued by the San Pedro local 167. [2]

On April 25, 1923, the Marine Transport workers Industrial Union, San Pedro Local 510, called a strike. This followed months of agitation and organization, and police harrasment. Beginning in November 1922, outdoor rallies were held at the corner of Fourth and Beacon Streets, in downtown San Pedro. A month later, the Los Angeles police department made its first mass arrest of IWW members, but this failed to deflate the organizing campaign. Harrassment increased when the walkout commenced in late April with the LAPD pledging to arrest picketers. The IWW responded by dropping leaflets from aircraft, and from a fast launch in the harbor. About 5000 workers in the East coast, as well as 3000 in San Pedro had walked off the job. Ninety ships in the Los Angeles harbor were immobilized.

The longshoremen and maritime workers were not only protesting low wages and working conditions, but also demanding the elimination of the “Fink Hall,” where company bosses were able to weed out union activists. They also called for the release of those convicted under the criminal syndicalism laws, then used to prosecute labor activists (Ralph Chaplin, for example, wrote “Solidarity Forever” in the winter of 1915; by 1918 he was incarcerated in Leavenworth penitentiary along with hundreds of other organizers).

In early May, as ships lay idle in the harbor and the IWW called for sympathy walkouts in other industries, the LAPD announced a ban on public meetings and began new rounds of arrests at the 4th and Beacon location that the strikers had been using for rallies. Upton Sinclair had continued to lodge public protests from Pasadena on behalf of jailed radicals, and to keep them supplied with books. Longshoreman Art Shields, who knew Sinclair from the picketing of Rockefeller headquarters after the Ludlow massacre, phoned him and asked for help. Although Sinclair was not the major figure in either Ludlow or San Pedro, his participation was crucial in developing sympathy for the strikers. Inspired by groups like the Women’s Trade Union League’s and the suffrage movement, Sinclair initiated some of the first efforts by intellectuals to gain widespread support for striking workers. By involving himself on behalf of these workers, Sinclair became, notes Dieter Herms, not only a chronicler of history but also a participant.[3]

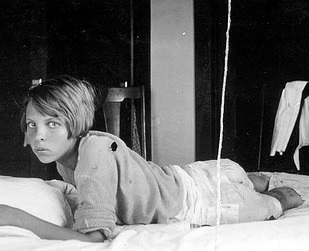

A year after the 1923 strike, the IWW Hall was again raided. May Sundstedt, age either 9 or 12, was hospitalized with serious burns after attackers, who including KKK members and Navy sailors, pushed her into pot of boiling coffee. Her mother was severely beaten and died two months later. Click for more photos. UW Libraries, Special Collections

A year after the 1923 strike, the IWW Hall was again raided. May Sundstedt, age either 9 or 12, was hospitalized with serious burns after attackers, who including KKK members and Navy sailors, pushed her into pot of boiling coffee. Her mother was severely beaten and died two months later. Click for more photos. UW Libraries, Special Collections

When San Pedro strike sympathizer Minnie Davis heard that the striking dockworkers needed somewhere to meet, she offered the use of her rented land behind 3rd and 4th St, on a hill overlooking the harbor.[4] The workers promptly dubbed it Liberty Hill. Art Shields remembers: “There was more singing than speaking on Liberty Hill…I've heard ‘Solidarity' on many picket lines in the last 62 years, but I've never enjoyed it as much as I did on Liberty Hill.[5]

Liberty Hill quickly came under attack. On May 14, eighty or so police officers, armed with clubs and guns, began climbing the hill. The 2000 strikers continued to sing as hundreds were arrested. The remaining strikers decided to carry their message from door to door. Five thousand men, women, and children wound through the streets singing, with jailed workers singing back from inside the San Pedro jail. Although a housewives’ committee was feeding many dockworkers, others were going hungry. Art Shields telephoned Upton Sinclair again.

Police Captain Plummer announced another ban on street meetings. Sinclair notified the strikers that the next move of the police would be to take over Liberty Hill, but that he would bring friends to challenge the police order. The next evening, Sinclair’s group huddled into a nearby café to strategize: the group included his brother in law Hunter Kimbrough, along with Kate Crane Gartz (who had come with her overnight bag all packed, prepared for jail). Sinclair told reporters: “We're testing the right of police to suppress free speech and assemblage. You'll hear what I say if you climb Liberty Hill.”[6] When Sinclair and his friends reached the summit, Sinclair stepped on a speaker’s box. Captain Plummer shouted. “I'm taking you in if you utter a word.” “My right to speak is protected by the U.S. Constitution.” Sinclair replied, and recited the First Amendment. As Art Shields remembered, Police Captain Plummer “grabbed the people’s novelist by the collar”[7] and arrested him.

Hunter Kimbrough then began to read the Declaration of Independence and was arrested, along with Prince Hopkins and Hugh Handyman. The officers, under orders not to arrest women, ignored Mrs. Gartz. Hunter Kimbrough wrote his own account of the arrest, describing how he rode on the running board of the overloaded police car, and how Sinclair lay on the floor in his cell rather than risk the lice-ridden cots. To the police, he called attention to the patriotism of the ancestors of those arrested to challenge charges that they weren’t “real” Americans.[8]

These IWW members were tarred and feathered in the June 14, 1924 KKK raid. Click for more photos of the raid's victims. UW Libraries Special Collections

These IWW members were tarred and feathered in the June 14, 1924 KKK raid. Click for more photos of the raid's victims. UW Libraries Special Collections

The men were not allowed to consult an attorney and were held incommunicado. Mary Craig believed that the police planned to harm Sinclair and to make it appear that either the IWW or the Ku Klux Klan was responsible.[9] The Los Angeles papers carried an unconfirmed report that the Klan planned to capture the four men. Mary Craig was visited by a Klansman during the time she was frantically trying to find her husband, who assured her that there was no plot on the part of his organization.[10] Art Shields issued a press statement saying Sinclair might be a victim of foul play. Two days later Upton Sinclair was released from jail.

Sinclair’s valiant efforts did not save the San Pedro walkout. Sailors left for distant ports, and the IWW’s isolation from the rest of organized labor meant that the San Pedro strike was one of the final actions of the Wobblies before in the split in the organization in 1924 and subsequent decline.[11] A week later, Upton Sinclair, out on bail, reappeared on Liberty Hill. Yugoslav-American writer Louis Adamic recounted: “Sinclair, a triumphant note in his intense voice, conducted doubtless the biggest meeting of his strike-following career, while over the bay of San Pedro hung a very full and very serene moon.” [12] Adamic concluded that the night that Upton Sinclair spent in jail for trying to read the Constitution was “among the pleasantest incidents of his career.”[13]

Police Chief Oaks stated to the press: “I hope Sinclair goes to jail if convicted ... I would rather deal with 4000 IWW than one man like Sinclair, who is what I consider one of the worst types of radicals.”[14] After he was released, Sinclair wrote an open letter to Chief Oaks, which was printed as a leaflet and widely circulated in Los Angeles. It began, “I thank you for this compliment, for to be dangerous to lawbreakers in office such as yourself is the highest duty that a citizen of this community can perform.”[15] Eventually Oaks was fired as one of the conditions of Sinclair’s dropping his civil suit for false arrest. Martin Zanger suggests that Sinclair’s experience at Liberty Hill may have stimulated his willingness to run a campaign for governor, noting that “subsequent California history might well have evolved differently had Mary Craig Sinclair held her husband to his promise to stay out of the Wobbly strike.”[16]Sinclair’s own version of the events and their aftermath can be found in the introductory chapter of The Goslings and in the postscript to Singing Jailbirds.[17]

Upton Sinclair went on to launch the Southern California branch of the American Civil Liberties Union, raising funds from wealthy sympathizers such as Charlie Chaplin, Congressman William Kent, and King Gillette. Sinclair hoped the ACLU would work for prison reform and release of political prisoners. Ella Reeve Bloor was still a good friend 25 years after she had helped him research The Jungle. She wrote after a visit to IWW members at Walla Walla Prison in Centralia, thanking him for his prompt reply to my SOS” About the prisoners, she wrote “It’s a wonder that they keep up their spirits as they do, after being away from Life itself for ten years.”[18] He wrote the play Singing Jailbirds to draw attention to the injustices that Bloor described.

Singing Jailbirds was set in the jail in San Pedro where the striking dock workers were imprisoned. German critic Dieter Herms writes “The generalization of the tragedy is achieved by means of the IWW chorus whose songs of proletarian solidarity punctuate the play in leitmotif fashion,”[19] In his Postscript to the play, Sinclair noted that similar conditions could be found in prisons throughout the country: “If anyone feels doubt on this question, he is advised to read “In Prison,’ by Kate Richards O’Hare.”[20] In North Dakota in 1919, O’Hare condemned the way mothers in America were encouraged to raise children for the military. She was sentenced to five years in jail, where she organized fellow prisoners.

Miriam Allen deFord, a journalist herself, wrote that she found Singing Jailbirds to be “a remarkable contribution to expressionistic drama. I should like immensely to see it adequately performed.”[21] But Sinclair needed funding for such a performance. He wrote to the New Republic: “We who care about free speech confront a difficult situation out here on the Coast…I undertook to raise the money to finance a production of Singing Jailbirds.”[22] He explained to potential funders that he would take no royalties. Following successful performances in Berlin in 1927, the play ran for two months at the New Playwrights Theater in New York. Later the play toured in both France and India.

Copyright (c) Lauren Coodley, 2015

[1] Mike Davis, “Sunshine and the Open Shop” in Metropolis in the Making: Los Angeles in the 1920’s, edited by Sitton and Deverell (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 102.

[2] San Pedro Daily Times, Oct 20, 1905.

[3] Herms, “Introduction,” Upton Sinclair: Literature and Social Reform, (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1990),

6.

[4] Letter from John Ahouse to Art Almeida, Feb 14, 1985. Her land was at 335 South Beacon St.

[5] Art Shields, “On the Battlelines” (International Publishers. 1986), reprinted in The Shoreline.

March 1995, 34.

[6] Art Shields, 34.

[7] Art Shields, 34.

[8] Hunter Kimbrough, “Cut Out That Constitution Stuff” Haldeman-Julius Weekly, 1923, cited in Zanger, 393.

[9] Mary Craig Sinclair, letter to John Hamilton, May 3l, l923, cited in Zanger, 394

[10] Craig, Southern Belle, 286.

[11] See Art Almeida “How San Pedro killed the Wobblies,” The Californians, July/August 1984.

[12] Louis Adamic, “Upton Sinclair on Liberty Hill,” excerpt from Open Forum 4:48 (November 26, 1927), Upton Sinclair Quarterly VI:I, 2 (Spring, 1982) 4.

[13] Louis Adamic, 4.

[14] Paul Irving, “Southern California ACLU Born on 4th and Beacon Streets,” Random Lengths, April 4, 1991, 1.

[15] Upton Sinclair. “Open Letter to Chief Oaks:” The Nation, June 6, 1923, 6.

[16] Martin Zanger, “The Reluctant Activist: Upton Sinclair’s Reform Activities in California 1915-1930,” PhD Dissertation, University of Michigan, 1971, 406.

[17] Sinclair, “Postscript” Singing Jailbirds, (Pasadena, Upton Sinclair: 1924). Upton Sinclair, The Goslings (Pasadena, Upton Sinclair, 1924)

[18] Letter from Bloor to Sinclair, Dec I7, 1929, Lilly Library.

[19] Dieter Herms, “An American Socialist: Upton Sinclair,” Upton Sinclair Centenary Journal 1:1 (1978), 52.

[20] Sinclair, “Postscript” Singing Jailbirds, (Pasadena, Upton Sinclair: 1924). Upton Sinclair, The Goslings (Pasadena, Upton Sinclair, 1924)

[21] Letter from DeFord to Sinclair, October 7, 1924, Lilly Library.

[22] Upton Sinclair, “Singing Jailbirds” The New Republic, n.d., 167.