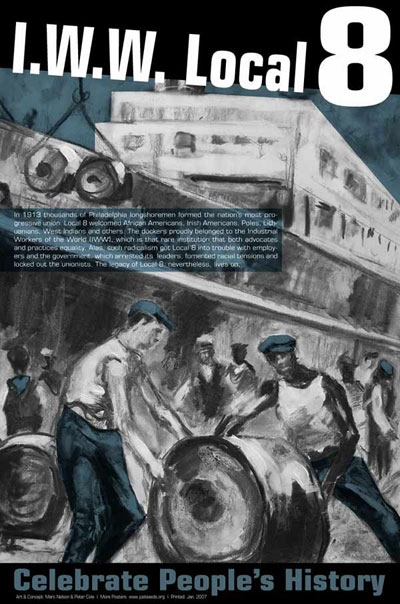

In the early 1900s thousands in Philadelphia belonged to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)—a militant, leftist labor union of workers in any and every industry imaginable. Local 8, which organized the city’s longshoremen, was the largest and most powerful IWW branch in the Mid-Atlantic and, most memorably, the union’s most racially inclusive branch. Indeed, there might not have been a more egalitarian union anywhere in the nation in the early 20th century than Local 8. From its inception, the IWW was committed to racial equality; however, African Americans played only a small role in the organization. By contrast, Local 8 possessed the largest contingent of African Americans in the entire IWW as well as its most significant black leader, Ben Fletcher. Local 8 dominated waterfront labor relations in one of the nation’s largest ports for the decade from 1913 to 1922. Even after Local 8’s decline, it continued to shape the waterfront for decades to come.

The Wobblies called for revolutionary changes to create a more just society where everyone could enjoy the fruits of industrialization. For this reason and like other socialists, the Wobblies were ideologically committed to ethnic and racial equality. In practice, though, most Wobblies in the USA (or Socialists, for that matter) were European Americans though the hardrock metal miners of the Mountain West were quite diverse. Undeniably, the success of Local 8 and prominence of the Philadelphia-born Fletcher (1890-1949) demonstrated that the IWW could put theory into practice.

In Philadelphia, one of America’s busiest ports due to the city’s massive industrial output, thousands of longshoremen toiled on both sides of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. They loaded manufactured goods like Baldwin locomotives to Stetson hats—everything “from battleships to buttonhooks”—and unloaded raw materials such as unrefined sugar from Cuba and coal from nearby mines.

Longshoremen—at that time, no women worked ships on the waterfront—suffered terribly at work. They toiled long hours, sometimes thirty-six hours straight for “the ship must sail on time.” The work was incredibly dangerous, as it was easy to fall into a hold, for a cargo sling hauling several tons of goods to snap, or to slip on a wet deck on a dark night. The work also paid poorly and was irregular, i.e. a longshoreman never knew whether his next ship might be tomorrow or next month. Even getting hired, the hated practice named the “shape-up,” was an enormous challenge: many longshoremen (some of whom were the children of freed slaves) called the shape as a slave market. Finally, employers enjoyed huge labor surpluses due to the desperate poverty among the hundreds of thousands of European immigrants and African American migrants from the South streaming into Philadelphia in this era.

Reflecting the city’s diversity, the roughly five thousand longshoremen in 1913 were about one third African American, a third Irish and Irish American, and a third European immigrants, especially Lithuanians and Poles. This ethnic makeup was not coincidental; employers counted on racism and xenophobia to keep workers from unionizing. As the pioneering labor historians Sterling Spero and Abram Harris wrote in their 1931 book, The Black Worker: “The Negro is now recognized as a permanent factor in industry and large employers use him as one of the racial and national elements which help to break the homogeneity of their labor force. This, incidentally, fits what they call ‘a cosmopolitan force,’ which frees the employer from dependence upon any one group for his labor supply and also thwarts unity of purpose and labor organization.”

Nevertheless, due to the oppressive conditions and povery wages, thousands of Philadelphia longshoremen struck in 1913 and quickly joined the newly chartered Local 8. Wobbly organizers actively promoted equality in the ranks, for instance mandating that a member of every major ethnic group be represented on the negotiating committee.

The presence of Fletcher, already a member of both the IWW and Socialist Party, no doubt reassured the thousand-plus African Americans that the Wobblies took black equality seriously. Fletcher was born in Philadelphia to parents who had moved up, in the late 19th century, from Virginia and Maryland. Fletcher was a radical, committed to overthrowing the capitalist system that exploited the hard work of the nation’s majority so that a few could amass fortunes. As the Wobbly leader “Big Bill” Haywood said, “I’ve never read Marx but I’ve got the marks of capital all over me.”

This photo of Ben Fletcher may have been a mug shot (Peter Cole photo)

Not surprisingly, black workers treated white workers and most white-dominated unions with skepticism. Booker T. Washington went so far as to encourage African Americans to cross picket lines of white strikers. Washington suggested that getting hired as replacements to strikers was the only way to break into exclusionary industries. Philadelphia longshoremen, though, ignored Washington’s advice. After several weeks in which the port of Philadelphia was effectively shut down, the multiethnic, interracial group won wage hikes with Local 8 representing the polyglot workforce.

With a foothold on the waterfront, Fletcher and other leaders effectively applied the militant, direct action tactics the Wobblies remain famous for deploying. Over the next decade, Local 8 dominated labor relations because its members proved willing and able to fight, on the job, for better conditions and higher wages. Crucially, Local 8 ended the shape-up. In its place, when employers needed workers, bosses rang up the Local 8 hiring hall and request people to work ships. Local 8 enforced its rule not by a contract with employers but, rather, expecting all workers to pay monthly dues that entitled them to that month’s button to prove membership. If an employer hired people not wearing the appropriate button, the rest of the gang would walk off the ship. It is impossible to know how many such “quickie strikes” occurred but they were a staple of the Philadelphia waterfront in this era, as they had been on and off ships for centuries.

Beyond winning raises and improving work conditions, Local 8 also insisted upon racial and ethnic equality. After its initial strike, the union integrated work gangs as well as meetings, social gatherings, and leadership posts—all unprecedented on the Philadelphia waterfront. Ben Fletcher, meanwhile, became nationally renowned for his speaking abilities and as the Wobblies’ best-known African American member. Though Fletcher was the most famous black Wobbly, a cadre of other African Americans also served in leadership posts in Local 8.

Poster designed by Mark Nelson and Peter Cole

World War I was a transformative experience for African Americans including in Philadelphia. With massive labor shortages creating newfound job opportunities, about 50,000 African Americans streamed into the City of Brotherly Love. While the migrants happily joined Local 8, their ticket to employment, few had experience with unions. Hence, the hundreds of new Southern black members had little commitment to unionism, let alone a revolutionary one. Yet, other African Americans—most notably a young socialist named A. Philip Randolph—praised Fletcher and Local 8 for promoting racial equality in the labor movement.

Predictably, Wobbly longshoremen experienced intense opposition from employers and the government. Employers never really accepted Local 8 and saw the war as a wonderful opportunity to collaborate with the federal government to eliminate Local 8. Similarly, President Woodrow Wilson and his administration used the war to crack down on Wobblies, Socialists, and other radicals—many of whom opposed the war effort as a way for capitalists get rich while working class people died in conscripted armies. Using new powers granted by Congress (though later found unconstitutional), the U.S. Department of Justice arrested Fletcher and five other local Wobbly leaders on charges of “espionage and sedition.” Fletcher was sentenced to 20 years in the federal prison at Leavenworth, Kansas along with every other Wobbly on trial.

While Local 8 survived this crisis, the newer leaders proved less capable than Fletcher and others. A huge strike in 1920—involving more than 9,000 maritime workers including many not even in Local 8—was part of a postwar wave of labor militancy that failed to achieve its hopes for an 8-hour day.

Finally, in 1922, waterfront employers took advantage of postwar America’s worsening labor and race relations, “locked out” Local 8 members, and broke their hold. This pushback was part of the first, nationwide “Red Scare” in which ferocious governmental and employer repression of leftwing radicals was justified using the wartime emergency. The wartime and postwar Great Migration also precipitated a huge backlash against the growing number of African Americans in Philadelphia and elsewhere. The bitter 1922 conflict also saw employers consciously targeting Local 8’s interracialism: appealing to specific ethnic groups (African Americans, Irish, Poles, etc.) to take the jobs of the others. Some African Americans stuck with the union, as did most of the European Americans and European immigrants. However, many of the less experienced, Southern blacks returned to work and the union’s hold was broken. A major factor in Local 8’s undoing was the racial wedge employers driven between the longshoremen.

Locally and nationally, in the early-mid 1920s, the IWW went into decline but its ideals persisted. In the late 1920s, the more conservative, rival International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) managed to bring unionism back to the port of Philadelphia. Even though, generally, the ILA admitted black workers, they were placed into segregated locals and with ultimate white leadership; in Philadelphia, though, the ILA accepted the power of black longshoremen and allowed for an equitable sharing of leadership positions at the local level, referred to as “checkboarding.” This unusual situation was an acknowledgement that the IWW had uplifted African American workers. Alas, the ILA was unable to resist the return of the shape-up and work gangs—once again—became segregated by both ethnicity and race. While the ILA took control of the port of Philadelphia, Wobbly ideals resurfaced in the 1930s in other ports, most notably Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Today, the history of Local 8 and Ben Fletcher are more widely acknowledged but generally remain unknown. While A. Philip Randolph is regarded as the most prominent African American in the

history of the US labor movement, few know that, as a young man co-editing the radical monthly The Messenger, Randolph championed Fletcher. Fletcher also should be considered among the most

important African American organizers of any sort in Philadelphia history. Arguably, Fletcher is among the most important African American organizers of any sort in Philadelphia history. Sadly, amidst the early 21st century housing bubble in formerly working class South Philadelphia, the building that housed the Local 8 hall was bulldozed for redevelopment. No sign marks the spot and Ben Fletcher, who passed away in Brooklyn in 1949, was buried in an unmarked grave. More recently, in the 2010s, a Wobbly-inspired union of food production workers in New York City cite Fletcher and Local 8 as inspiration for organizing the next generation of immigrants and workers of color.

Bibliography:

Copyright (c) Peter Cole, 2015