by Wren Cavanaugh and Emma Mantovani

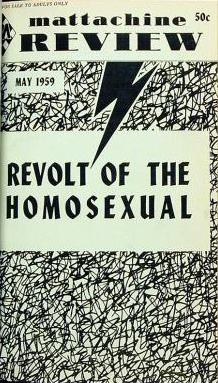

1959 cover of Mattachine Review, published in Los Angeles (Wikipedia)

1959 cover of Mattachine Review, published in Los Angeles (Wikipedia)

Throughout the twentieth century, LGBTQ communities in the United States relied on print media as a primary means of communication, organizing, and cultural expression. Periodicals (magazines, newspapers, newsletters, and journals) were critical cultural instruments where queer people could see their lives reflected, share information, and debate political strategies. Long before digital media, these publications helped transform scattered individuals into identifiable communities.

The modern history of LGBTQ periodicals began in the early Cold War era. In the 1950s, homophile organizations such as the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis produced some of the first sustained gay and lesbian publications in the United States. Titles like ONE (founded in Los Angeles in 1953), Mattachine Review (1955), and The Ladder (1956) combined essays, fiction, political commentary, and news aimed at fostering a sense of collective identity (Streitmatter). These publications were cautious in tone and presentation, shaped by censorship laws, postal regulations, and the risk of police harassment. Editors often framed homosexuality as a minority condition deserving understanding and legal reform rather than as the basis for radical social change. (Continue introduction)

This page tracks nearly 500 periodicals published between 1953 and 2000. The maps are hosted by Tableau Public and may take a few seconds to respond. If slow, refresh the page.

Move between four maps and charts using the tabs below

Introduction continues

The late 1960s marked a turning point. The rise of gay liberation after the Stonewall uprising in 1969 coincided with a dramatic expansion of LGBTQ print culture. New newspapers and magazines rejected the restraint of the homophile era and openly embraced confrontational politics, sexual expression, and collective pride. Periodicals such as Come Out!, Gay Power, and The Advocate reflected this shift, serving both as news sources and as organizing tools tied to local liberation movements (Rodger). Publishing activity increased rapidly in major urban centers where printing infrastructure, activist networks, and potential audiences were most concentrated.

During the early 1970s, lesbian-feminist publishing emerged as a distinct and influential sector of LGBTQ print culture. Publications such as Lesbian Tide, Lavender Woman, Amazon Quarterly, and Lesbian Connection centered women’s experiences and critiqued sexism within both the gay movement and the broader feminist movement. Many were produced collectively, distributed through informal networks, and sustained through subscriptions and donations rather than advertising. Scholars have noted that lesbian periodicals were often more geographically dispersed and less commercially visible than gay male publications, reflecting both political commitments and structural barriers to funding (Streitmatter).

By the late 1970s LGBTQ periodical publishing had entered a new phase. A growing number of newspapers and magazines achieved stable circulation, regular publication schedules, and advertising revenue. Local gay and lesbian newspapers became fixtures in cities such as San Francisco, New York, Chicago, Boston, Seattle, and Washington, D.C., providing coverage of politics, culture, nightlife, and community events. National magazines expanded their reach, contributing to a shared sense of LGBTQ public life across regional boundaries.

The period from 1979 to 2000 was also profoundly shaped by the AIDS epidemic. Beginning in the early 1980s, LGBTQ periodicals played a critical role in disseminating information about the disease, challenging government inaction, memorializing the dead, and mobilizing political responses. Many newspapers shifted editorial priorities toward investigative reporting, public health education, and advocacy, while also serving as spaces for grief and collective memory. The epidemic reinforced the importance of local publishing even as national media attention remained very limited or hostile.

At the same time, LGBTQ publishing became increasingly stratified. Publications with access to advertising and large urban readerships were more likely to survive, while smaller, radical, or identity-specific periodicals often struggled to sustain themselves. Transgender publications, publications by and for people of color, and explicitly anti-capitalist or separatist journals frequently operated outside commercial channels and left fewer traces in mainstream directories (Rodger).

Reading the Maps

The interactive maps on this page locate LGBTQ periodicals by place and founding year, especially those active between 1979 and 2000. Major metropolitan areas appear as dense publishing hubs, reflecting access to resources and audiences. Filters allow you to view publications oriented toward specific LGBTQ audiences, highlighting the diversity of print culture within the movement. These maps are best understood as representations of publishing activity within a particular commercial and archival framework rather than as a complete inventory of LGBTQ print culture.

The data for these maps and charts were compiled mostly from Ulrich’s International Periodicals Directory, 1979–2000 (R.R. Bowker, 2000), with additional research in other sources to locate some periodicals from earlier decades. Ulrich’s is a reference directory designed primarily for advertisers, librarians, and publishers. It privileges periodicals that sought advertising revenue and had sufficient circulation to be commercially relevant. The directory is also oriented toward the Anglophone world, particularly North America and Western Europe.

As a result, the dataset disproportionately reflects publications that were published in the 1980s and 1990s and were more commercially oriented and less politically radical. Lesbian-run publications, trans periodicals, publications by and for people of color, student newspapers, church newsletters, and short-lived grassroots publications were less likely to be indexed. Scholars of LGBTQ media history have emphasized that these forms of publishing often circulated through informal or community-based networks that were poorly captured by commercial directories (Streitmatter).

For these reasons, the maps should be read as a glimpse into which LGBTQ periodicals were visible within an advertising driven information economy. The absences in the data are historically meaningful as they point to inequalities in access to funding, infrastructure, and visibility within LGBTQ publishing itself. Despite these limits, the maps reveal how print culture helped sustain LGBTQ communities during a period of rapid political, cultural, and public health change. They also invite one to ask broader questions about power and representation such as who had the resources to publish and which voices reached national audiences.

Works Cited

Rodger, Brett Josef. The Queen’s Vernacular: A Gay Lexicon. Routledge, 2017.

Streitmatter, Rodger. Unspeakable: The Rise of the Gay and Lesbian Press in America. Faber & Faber, 1995.

Ulrich’s International Periodicals Directory, 1979–2000. New York: R.R. Bowker, 2000.

“Exploring 70 Years of Lesbian Publications, from 1940s Zines to Modern Glossy Magazines.” News Is Out, Oct. 2023.

Sources: Ulrich’s International Periodicals Directory 1979-2000 (New York: R.R. Bowker, 2000); Underground Press Collection: A Guide to the Microfilm Collection (University Microfilms International, 1986 and Hoover Institution, 1988); University of Oregon Underground Press Directory; University of Washington Underground Press Directory; Independent Voices: An Open Action Collection of an Alternative Press.

1959 cover of Mattachine Review, published in Los Angeles (Wikipedia)

1959 cover of Mattachine Review, published in Los Angeles (Wikipedia)