by Selena Voelker

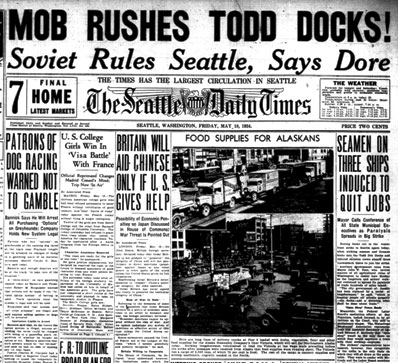

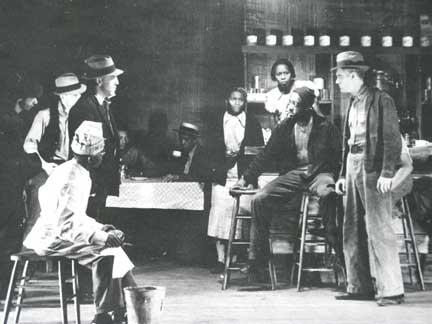

Clifford Odets' iconic 1935 play Waiting for Lefty was first produced for The Group Theatre in New York City, pictured above. Lefty, a play about a taxi drivers' strike, sought to engage the audience with the production and meld leftwing labor politics and artistic forms. Seattle's production of Lefty, in 1936, proved to be contentious because of the long history of labor radicalism in the state.

The establishment of the government’s Federal Theatre Project in 1935 allowed artists during the Great Depression to flourish with the help of federal funding, and underwrote new theatre works and interpretations. Federal funding allowed the multiple theaters in large cities like New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and Seattle to continue their work during the Depression. The Depression and subsequent federal funding contributed to the flowering of a new, socially conscious movement in American drama. Typified by The Group Theatre in New York, this generation of dramatists was moved to write and perform plays that functioned as social commentaries on the inequality, poverty, and crisis of 1930s America.[1] Aided by the Federal Theatre Project, this leftist theater would sweep the nation, arguably starting in New York and making its way across the United States to Seattle, where its production illuminated Seattle’s labor politics and the potential power of arts in social criticism and reform.

Waiting For Lefty, written by Clifford Odets about a 1934 taxi union strike, is one of the best examples of this tradition, written while Odets was working with The Group Theatre in New York. Coming in the midst of the Depression and labor struggles of the 1930s, the play was labeled as Communist propaganda by critics. However, the public debate over Lefty shows how socially conscious theatre was seen as a powerful force in shaping American public opinion, or perhaps in illustrating tensions already present. Nowhere is the power of 1930s theatre shown more clearly than in the circumstances surrounding the Seattle production of Odets’ play.

Odets’ play had gone through many successful runs, most notably in New York, and created a buzz of both praise and outraged criticism.[2] The Seattle Repertory Playhouse (SRP) decided to produce Waiting for Lefty in January 1936, after a private reading of the play at the home of SRP directors Florence and Burton James, to University of Washington colleagues and friends.[3] The decision to stage the play in Seattle resulted in a showing of only one night in Seattle, and resulted in the blacklisting of the SRP in one of the city’s major papers, the Seattle Times.

The production of Lefty came shortly after the 1934 maritime strike which brought two radical labor leaders to national prominence: David Beck, later leader of the Teamsters in the Seattle area and Harry Bridges, a radical who many accused of bringing communism. The connection between Beck and Washington’s Governor Clarence Martin had been recently forged, and the allusion to labor racketeering in Lefty could only have been unwelcome to them and their supporters. In addition, the owners of the playhouse, Florence and Burton James, had a history of being involved with labor unions and Florence James had just completed a tour of Soviet Russia’s theatre.[4]

However, what made Lefty so controversial and threatening for Seattle area authorities was not merely the play’s reputation as Communist propaganda, but its resonance on Seattle-area labor politics. By reading both the playhouse logs and Mrs. James’s unpublished memoir, Fists Upon A Star, we can decipher not only the play’s impact in Seattle but a larger picture of art, politics, and labor at the time. Even more, we can begin to examine how the arts functioned as arenas for social debate.

The Group Theatre, Clifford Odets and the writing of Waiting for Lefty

Clifford Odets was one of a number of socially conscious playwrights of the 1930s, along with Sidney Kinsgley, Irwin Shaw, Paul Green and John Howard Lawson. In her unpublished memoir Fists Upon a Star, Florence James singled out Odets as one of the most influential to her understanding of the "social content" of the theatre in the period.[5] Florence James and her husband, Burton James, lived and worked in the New York theatre scene in the 1920s and also were quite socially conscious, which would have made them well aware of this new movement in drama.

The Group Theatre (TGT) was at the forefront of this new “social content” movement. It was a group of actors, directors and playwrights that formed in New York at the beginning of the Great Depression. Unlike Broadway producers who hired actors on a play-by-play basis and paid them based on roles, TGT kept a permanent company of actors and paid a consistent salary based not on merit but on inclusion in “the group.” As Harold Clurman, one of the founding directors of the TGT writes in his memoir The Fervent Years, “I loved to go to the theatre because the presence of the actors—their aliveness, the closeness of the audience, and the anticipation of a communion between all of them in terms of imagination…was the very flower of large social contact.”[6]

This philosophy of connecting the actor and audience in mutual experience and participation in producing a work of art guided TGT’s company. Clurman’s quote also illustrates the idea of “social content” that TGT sought to bring to the stage as they communed with and educated their audience. TGT strove to make theatre something more than a passive viewing experience; they wanted their work to having meaning for the audience, as the idea of a communion between actor and audience highlights. In this way, The Group Theatre strove to make culture, not merely art.

Clifford Odets appears in Clurman’s memoir as a young man at the first meeting of The Group Theatre. Clurman cites him as someone he would have definitively labeled “as a strange young man” had they not grown to become good friends who lived together for some time during the thirties. From Clurman’s memoir it appears that Odets had an early attachment to the lower classes, having lived a life of poor means himself. According to Clurman, “it was as if he wanted to be one with semi-derelicts.”[7] Indeed, it appears that Odets had a passion for the neglected, as he and Clurman spent many nights between January of 1933 and September 1933 wandering the dejected areas of New York at night.

During the Great Depression no group became more neglected than the poor working class, and it appears to be this attachment to the poor working class that drove Odets to write works like Waiting for Lefty. However it is important to note that, to Clurman, Odets was not writing as a Communist sympathizer per se, but as an impassioned youth who “wanted to explain what had happened to them [the degenerates], and, through them, to express his love, his fears, his hope for the world.”[8] Odets writing, from this perspective, takes on an almost hopeful tone. In the spirit of The Group Theatre, and Florence James’s discussion of “social content,” Odets strove to make a connection between the audience and actors to inform them of the plight of the people.

The connection between audience and actors was not only theoretical for Odets. It can be seen in the play, as several scenes require that the audience—or strategically placed actors—perform lines. These cues appear as “The Voice” in the script, and thus the audience becomes a participant of the union meeting taking place on stage. The stirring end of the play, and probable reason that such a short work could be considered dangerous, invites the audience to respond to the taxi drivers’ call for a strike. The audience’s answer is not left up to the director or the actor: cues direct the provocative line “Well, what’s the answer?” as “To Audience.”[9] That audiences took up the call of “strike!” with ample enthusiasm seems planned by the playwright. And given Lefty’s Communist ethos (one scene has actors debate with each other about taking up the Communist Manifesto) the choice of the audience to participate could be seen as dangerous to capitalist America.

The first showing of Waiting for Lefty was at New York’s old Civic Repertory Theatre on 14th Street, and took place on January 5, 1935.[10] The play was a success and the culminating scene more than succeeded in integrating the audience into the framework of the play. As would occur in the Seattle Repertory Playhouse showing of Lefty,when asked “Well, what’s the answer?” the audience response of “strike!” was overwhelming. As Clurman writes, “The audience, I say, was delirious. It stormed the stage, which I persuaded the stunned author [Odets] to mount. People went from the theater dazed and happy: a new awareness and confidence had entered their lives.”[11] The “new awareness” was what Clurman termed a “strike for the greater dignity, strike for a bolder humanity, strike for the full stature of man.”[12]

Given its reception in New York, Lefty quickly became a symbol of the proletarian revolution and was staged across the country. The play was new, it was exciting, it sent audiences into a “frenzy,” and it captured the feeling of the 1930s that something needed to be done. While the play had a Communist theme, it was quickly picking up popularity, and became a sort of “fad” as SRP co-founder Albert M. Ottenheimer would later write in the SRP log books. A Dr. Winther and J.L. Norie, both University of Washington professors, came to speak to Ottenheimer on June 15, 1935 to tell him “that he [Winther] had heard that a petition was being circulated asking The Playhouse to stage Clifford Odets’ current ‘proletarian’ success, Waiting For Lefty.”[13] Important is the portrayal of the play as a “current success.” For these two professors, the play was a popular fad, one that University of Washington professors wanted to see so much that they were petitioning the Playhouse to do so. Yet these professors were not the working class portrayed in Waiting for Lefty, so the interest in the play and its resonance in Seattle require explanation from outside of the theatre world.

Seattle labor and politics in the mid-1930s

During the 1930s, growing radicalism in working-class politics and union movements led to an anti-Communist reaction by many Seattle politicians. Communism, in this period, was part of a broad spectrum of leftist politics, direct action strategies, and working-class movements for change that many workers and leftists responded positively to. Local workers’ hopeful vision of Communist ideas was the reason many politicians were eager to use Communists as a scapegoat or target of repression.

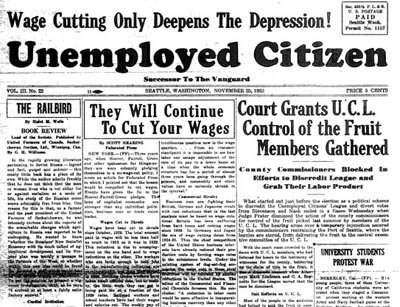

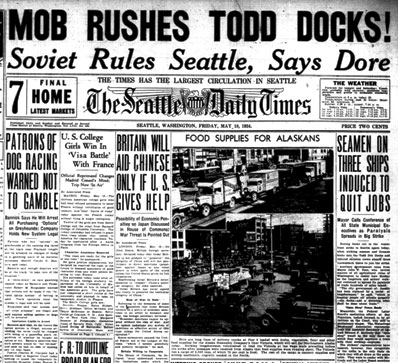

In the summer of 1934, West Coast longshoreman struck for 83 days, closing ports up and down the West Coast. In Seattle, the longshoreman galvanized the city's labor movement and -- as this Seattle Daily Times frontpage shows -- inspired fears of the labor movements' strength and radicalism.

The election of Seattle Mayor Frank E. Edwards was most directly related to his stance on City Light and public power. However, what is of important note here is the “red scare” tactics Edwards used in his campaign, directing much of his ire toward the Communist-influenced Unemployed Citizens League. In his push to be elected Edwards also went on a smear campaign of the other candidates, Hearst and Scripps. The Seattle Review,which endorsed Edwards, ran columns against Hearst and Scripps like “Reds in plot to Ruin City” and “Red Mayor is Next Step.”[14] Edwards’s campaign is one of many examples which illustrate the usefulness of red-baiting, which while not new to the city (indeed the city government’s response to the 1919 general strike hit upon a decidedly anti-communist bent) illustrated the potential social explosiveness of the period, exacerbated by record unemployment.

The West Coast maritime strike of 1934 was a watershed for the labor movement and set the stage for the Seattle Repertory Playhouse’s showing of Waiting for Lefty in January 1936. The maritime strike was born from the hopes of labor for greater federal recognition, after the passage of Roosevelt’s pro-labor New Deal legislation, and from longer traditions of struggle among maritime workers. The longshoremen’s union, the International Longshoreman’s Association (ILA), sought both wage increases and official recognition from their employers as a collective bargaining unit. The employers’ refusal, the strikes in other West Coast ports, and the ILA’s belief that they could win under the new labor-friendly Roosevelt administration, led the Seattle local to vote in favor of the strike by 995-12, helping to initiate an eighty-three day strike that closed ports up and down the West Coast during the spring and summer of 1934.[15]

The stage was set for the entry of Dave Beck and Harry Bridges. Dave Beck was the leader of the local Teamsters organization, a union that controlled the rights to truck shipping in the Seattle area. The Teamsters union was sympathetic to the maritime strike, waiting for word from Beck as to when they should and should not allow trucks through the picket lines and into the port. Dave Beck was also sent to San Francisco by Governor Martin as his representative in negotiating an end to the strike, which had gotten so bad that Martin had considered calling in the National Guard. While these particular negotiations did not go through, Beck serving as Martin’s representative forged an alliance between the two. Beck’s support of Martin was not forgotten, and the governor more than paid him back during the Seattle Times’ newspaper strike in August of 1936. Governor Martin was not the only friend that Dave Beck made during the maritime strike, however.

The 1934 longshore strike involved street battles, pickets, and protest. Here, Tacoma and Seattle longshoremen lead a

strikebreaker, identified as 'Iodine' Harradin, off the Seattle docks

during 1934 strike. (Port of Seattle photo.

Ronald E. Magden Collection.)

Historian Richard Berner makes a good point about Beck’s position when he writes that “On the Pacific Coast, he clearly was emerging as the best hope of the conservative elements in the labor movement, bent upon preserving the craft structure of union organization along with its narrowly defined vested interest in job control. With this orientation was allied a distrust of rank-and-file control of the union leadership; referral of leadership decisions to the rank-and-file threatened the union bureaucracy” (italics added).[16] Beck’s stance on labor and his situation is eerily similar to that of Fatt, the cautious union boss in Waiting for Lefty who gets overpowered by the workers in their push for a strike. Conservative unions, such as Becks’ Teamsters, didn’t help the worker through wage benefits or work area improvements. In fact, a conservative union, such as the structure of the taxi drivers’ union in Waiting for Lefty, can be used as a way to keep a lid on perceived worker radicalism by stalling negotiations and diffusing calls for more radical action. It is then of special note that not only was Becks’ labor politics quite similar to the antagonist of the play, and that during 1935 and 1936 Beck had definite pull with both the state governor and Seattle city mayor. The re-entry of labor into the Seattle politics was the backdrop to the SRP’s performance of Waiting for Lefty and gives clues to the play’s reception.

Florence and Burton James and The Seattle Repertory Playhouse

After meeting at Emerson College, Florence and Burton James moved to New York City in the hopes of establishing their own theatre company. When Nellie Cornish offered the Jameses teaching positions as heads of the drama department at her new school in Seattle, Cornish College of the Arts, the couple took the job. Mrs. James looks back kindly at her years working at Cornish in her unpublished memoirs, but the couple ended up deciding to leave the school after the school’s board denied their request to produce Pirandello’s avant-garde piece Six Plays by an Author. Due to the nature of the play, which would have required students to be nude on stage, the board also required the Jameses to submit future plays to them for screening before they could be used in the Cornish’s drama department. This represents the couple’s importance to the development of avant-garde theatre in Seattle, and also marked their decision to leave Cornish and start their own company as a vehicle for their non-conformist, artistic sensibilities.

Florence Bean James. Born in 1892, she came to Seattle in 1923 with her husband Burton to teach drama at Cornish School. The Jameses co-founded the Seattle Repertory Company, where they explored progressive politics and artistic production. (Image courtesy of the University of Washingon Special Collections Library)

The Christian Science Monitor announced the Jameses decision to start The Seattle Repertory Playhouse on July 10, 1928.[17] Florence James described the theatre as a community theatre that all aspects of society, including labor, could become involved in.[18] Her specification of labor as part of the playhouse’s community in this article almost seems to presage the later scandals which came from the SRP’s staging of Lefty and another play about a longshoremen’s strike, Stevedore, suggesting that it was her inclusive vision of community rather than her politics that made her a target of censorship. It is important to take into account that Florence James’s memoir was written after the McCarthy era, and that her remembrance of the past may be colored by a defense of her actions in the face of anti-communist, anti-labor witch-hunts. However, her inclusion of labor at this early stage is a sign of things to come, as Florence James in particular became more involved in politics around Seattle as the unemployment crisis deepened during the Great Depression.

Florence James’s unpublished memoir, Fists Upon a Star, describes the Seattle she and Burton first encountered in terms saturated with images of the city’s labor relations and political radicalism:“the wage slavery of the mines and mills [came] to Seattle to find freedom and security…freely live their beliefs in co-operation, religion and socialism.”[19] In this short introduction Mrs. James attempted to capture the spirit of labor in Seattle, the spirit of a city that, in 1919, went on a city-wide general strike. For Mrs. James this spirit was good for the theatre, for in her own words, it was “a climate where imagination and hard work could flourish.”[20] The fact that Mrs. James felt the need to add this section to her memoirs, even if nostalgically, shows her passion for social problems, as well as the inspiration she took from the ferment of the labor movement, and serves as a good introduction to the sympathetic interaction between the Jameses, particularly Florence James, and area union and labor groups.

The Jameses consciously worked with and encouraged unionization of the theatre business, particularly through their work with the International Association of Theatrical and Stage Employees (IATSE). What is most notable about here is that the Jameses did interact with the union, as this was not yet common practice. In Mrs. James’s memoir, Cornish College had not been using union stage hands prior to the Jameses’ arrival, and the union was known to “picket any production held in a downtown theater” in which their hands were not working. Only later, due to his work with the union, did Burton James receive a lifetime membership card with IATSE.[21] In addition, the actors of the Playhouse eventually formed their own union, the Organized Workers of the Seattle Repertory Playhouse, whose goals seemed to be focused on making sure the Playhouse was doing all it could to advertise their productions.[22] While these actions didn’t ruffle any feathers, it does show the Jameses’ willingness for innovation, in reference to other theaters, and their belief in the necessity of unions.

The Jameses’ pro-union sympathies earned them the ire of the American Legion, a veterans’ aid society founded in 1919 that tended toward increasingly conservative politics and defenses of “Americanism”. The Playhouse was in the practice of renting out their space to groups as a way of bringing in extra income. Any group seemed to be welcome as long as they could pay, and while this can be seen as act of open-mindedness by the Jameses, it was taken as an act of radical political motives by others. In particular, the American Legion: on April 22, 1935, the Legion wrote a letter to the Playhouse in protest of a socialist church group who was renting space in the Playhouse. The middle section of their letter reads: “We understand that these services are decidedly communistic, and in as much as our organization represents true and ideal Americanism, we feel that it is our duty to make this protest.”[23] While the American Legion is most decidedly a reactionary group, it is of note that the Playhouse, six months prior to the showing of Lefty, had been attracting attention about its perceived communist sympathies. That this became a matter of heated public debate speaks to the charged atmosphere of Seattle during this period.

It was Florence James’s brief connection to the Unemployed Citizen’s League (UCL) and the Interprofessional League of Seattle (ILS) that stirred public opinion the most in the months preceding the staging of Waiting for Lefty. The Interprofessional League of Seattle was a group whose goal was “to work for the passage of the [highly controversial, progressive] Lundeen Social Security Bill.”[24] The Social Security Administration is taken for granted later in the 21st century, but at the time, it was a leftist idea associated with radical social movements and ideas of redistributing wealth. Florence James, as an elected chairwoman of the group, allowed them to use the Playhouse as a meeting space. While no complaints were lodged about her connection to the ILS, her work with them does undermine her later assertion in that she had no political connections or ambitions.

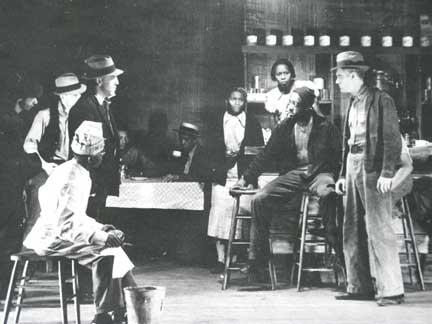

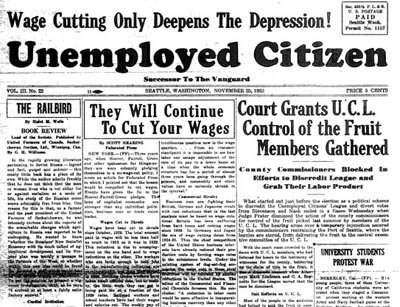

The Unemployed Citizens' Council published after their founding in 1931, and contributed to the radical culture in Seattle during the 1930s.

The UCL grew out of the unemployed councils of the early Depression. Not originally a communist-leaning league, the early UCL fought for a $4.50/hour wage and was the beginning of what later became the “production-for-use” political platform. It wasn’t until after a failed march to the Washington capitol and a clash with the Communist Party in 1932 that UCL leaders in the Seattle area were systematically replaced by members of the Communist Party. It was in this capacity that Florence James accepted the invitation to talk to the UCL in December of 1935 about her summer trip to the Soviet Union (and her Moscow theatre tour in particular), scarcely a month before the showing of Waiting for Lefty at the Playhouse. Mr. Ottenheimer’s assertion that “she didn’t learn until afterward that they are considered a radical group,” is preposterous for a woman who was active in her own political group.[25]

Out of Florence James’s control, the Playhouse claimed, was the assertion that “they [the UCL] had advertised her speech with mimeographed sheets in such a way as to make her speech sound like a political one.”[26] The entire situation of Mrs. James speaking to the UCL, as well as her trip to Soviet Russia, speaks not only to the Playhouse Boards’ concern with seeming “too radical” in the lead-up to the showing of Waiting for Lefty, but also to the underlying tension in Seattle over radical politics.

Florence James defended her actions by pointing out that she “was asked to speak on my experiences to any number of organizations and clubs…as I had not refused anyone, I did not consider refusing to speak to them…even if the audience might consist of some political heretics and agitators.”[27] Two things can be gleaned from this statement. The first is that Mrs. James was aware of the political leanings of the UCL, even if she did consider them “political heretics and agitators.” As she also was aware that few people traveled to the Soviet Union at the time, it seems strange that she later seems surprised that people assumed she was a Communist sympathizer, or a member of the Communist Party herself. Second is that Mrs. James gave her speech on Moscow to multiple groups, and the talk to the UCL may have been the key ingredient to onlookers as to her political sway.

That her memoir was written after the red scare is important in reading between the lines. Having been accused of being a Communist, it seems logical that Mrs. James attempted to distance herself as far as possible from the Communist Party. As she makes sure to add in her memoir, a board member of the Playhouse was keen to point out to her that she made her “speech too well. You are going to get people to like the Soviet Union.”[28] While Mrs. James may truly have only wanted to share her experience with Soviet Theatre, the compounded timeline from her trip, her talk to the UCL, and the production of Waiting for Lefty was part of the atmosphere that awaited the production of the play, and at least part of the reason for the volatile response Lefty received. And despite her later denial of her political leanings, it seems clear that the Playhouse’s decision to stage Lefty came out of the pro-union sympathies and radical milieu in which the Jameses moved.

The Jameses’ politics were not made an object of public controversy, however, until after the staging of Waiting for Lefty. Mayor Smith declared the beginning, on October 17, 1935, of a Civic Theatre Week for Seattle, urging everyone to attend the Seattle Repertory Playhouse. The press release, as recorded in the Playhouse logs, read:

Whereas, the Repertory Playhouse fills a place in our city which is beneficial to the residents of this city and an attraction which is popular with the residents of nearby cities…Whereas, the Repertory Playhouse through its existence is beneficial both as an amusement center, as well as from a business standpoint,— Now therefore, as mayor of Seattle, I, Charles L. Smith, hereby proclaim the week of October 21 to 26 inclusive ‘Civic Theatre Week’.[29] (italics added)

The Negro Repertory Company was a part of Washington State's Federal Theatre Project, led by the Jameses, and brought progressive social and labor politics to Seattle's stage. Shown here is the Negro Repertory Company's production of Stevedore, about a longshoremen's strike, in Seattle, 1936. Click on the image to be taken to a special essay about the Negro Repertory Company. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Librrary Special Collections.)

Of note is the repeated rhetoric that the theatre, and specifically the Seattle Repertory Playhouse, is beneficial to the people of Seattle because of its contribution to the local economy. Theatre here is an integral part of the city’s life, to the point that a week was set aside in appreciation of the Playhouse. The theatre gives something to the city, notably amusement and business, but in the first sentence in which Mayor Smith writes that the Playhouse “fills a place in our city which is beneficial to the residents,” is much more broad. It is this ambiguous quality of community that the allowed the Playhouse both to be recognized in a Civic Theatre Week, and raise such a controversy when it staged Waiting for Lefty. A true “community theatre,” as Mrs. James earlier envisioned the Playhouse, was exactly what the SRP was becoming, as the controversy over Lefty showed how much of a stake city residents felt they had in its productions.

The Production and Aftermath of Waiting for Lefty in Seattle

The decision to produce Waiting for Lefty and the preparation leading up to the play differ greatly from the story described in Florence James’s unpublished autobiography from the 1940s and the Playhouse logs written by Mr. Ottenheimer in the 1930s. Mr. Ottenheimer, described in a recent history as “a UW alumnus who had served as press agent, actor, director and playwright with the Seattle Repertory over the years,” was the meticulous keeper of the Playhouse log books, even taking care to record the weather every day.[30] Between the two stories it is possible to obtain a good idea of how Waiting for Lefty came to be at the SRP.

In Florence James’s account, the play was read on a Sunday at their home to a group of University of Washington professors to much applause, and was promptly turned into a special Sunday showing at the Playhouse. As she writes, "Mr. James, as was his custom, read it one Sunday evening for some supper guests who were university professors. They immediately set to work to find a way for a production. What it would cost to finance it, for we had no money for experimentation, they decided on that Sunday evening. They agreed to sell tickets to cover the cost and we produced it. It is difficult to imagine the uproar this one-act caused. The professors oversold the house. Everybody seemed to want to see it.”[31] (italics added)

Her writing makes it appear as if the play was produced almost on a whim, and in response to the professors clamoring for the play. However, if Mrs. James’s account is taken at face value, it would then seem that not much thought or preparation went into the production. While the reading of the play was obviously exciting to the professors—and one can imagine them and the Jameses having a stimulating intellectual conversation about the work—to rush into a production of a controversial piece seems irresponsible, especially in light of Mrs. James’s recent speech to the UCL. On one hand her surprise at the “uproar” the play caused does seem to support the idea that Mrs. James at least was unaware of the social context of the play. However, this hardly seems likely given the Jameses deep engagement with radical and avant-garde theatre in the 1930s, and one must remember that she is writing from the post red-scare perspective. Perhaps the most important part of the story of Lefty to be gained from Florence James’s memoirs is how much she felt she needed to downplay the radical politics and pro-labor intentions of the Playhouse in deciding to stage the piece, which speaks the strength of anti-Communist repression she later faced.

Built in 1930, Seattle Repertory Playhouse was acquired by the University of Washington after the theatre closed in 1950. In 2009 it was remodeled and is now called the Floyd and Delores Jones Playhouse. (Image courtesy of University of Washingon Special Collections Library).

The Playhouse logs tell a different story. The rationale for choosing Lefty in the logs supports the argument that the play was performed because it was an exciting dramatical trend. Ottenheimer writes: “Apparently the argument that this is an experiment, that we are only trying to reflect the new and vital trend in the theatre, exemplified by every major production in New York, commercial and otherwise, this season, and that we have no choice, if we wish to keep in the live current of drama, doesn’t convince them” (italics added). [32] By choosing to stage Lefty,the Playhouse was elevating the artistic value of its productions and keeping its work cutting-edge. Lefty was something new and dangerous, which made it exciting.

According to the log books, a much more reliable source for dates, after the reading of the play at the Jameses’ home, there was a read-through of the script at the Playhouse and casting calls were held on November 3, 1935.[33] Ten subsequent rehearsals followed, beginning two days after the casting call and filling the time until the play’s showing on January 15, 1936, almost a year after the first showing of Lefty in New York.[34] From the log books the decision to stage Lefty appears well planned, as opposed to the quick turnaround and impulsive production that Mrs. James presents in her unpublished memoir.

Quite interesting is the fact that Florence James was attempting to find another act to combine with Waiting for Lefty. On November 11, Mrs. James was attempting to get a local modern dance company to put on a performance before the play.[35] She also considered adding Lefty on to the end of the already playing set of shorts After Such Pleasures.[36] However, this play was already coming underscrutiny for its use of vulgar language and it is possible that this was the reason Lefty retained its position as a special Sunday showing. Possibly her search to find additional material to play with Lefty was an attempt to dampen the radical effect of the play.

The American Legion also weighed in heavily in the month before the showing of Lefty. Its complaints and threats are documented in the Playhouse logs. According to Ottenheimer, Judge Macfarlane [a member of the Playhouse board] called Mrs. James early this evening to tell her that he had three protests from the American Legion about Waiting for Lefty. He said that some of them had announced their intention of seeing it to censor it. Mrs. James explained that that won’t be possible, since all the tickets are sold… and there won’t be any on sale.”[37]

Mrs. James seemed more than happy to inform them that the tickets had been privately sold and that they would be unable to view the play. The fact that the American Legion wanted to censor it speaks to the idea that the play would run multiple showings. The idea of censorship also shows how Waiting for Lefty was considered political propaganda by some conservative groups, and the careful ways Playhouse staff sought to deflect their protest.

As with all plays staged at the Playhouse, Mr. Ottenheimer took detailed notes of the opening night performance of Waiting for Lefty on Sunday January 12, 1936.[38] His overall description of the play was that

It has a message, a bitter tirade against racketeering in trade unions, and, likely, something of a communistic bias, but the play transcends these. Its dramatic excellence, excitement and power cause theses other considerations to fade into the background. Waiting for Lefty admirably fulfills a quotation Brooks Atkinson adopted from one of his correspondents in a recent issue of the New York Times, to this effect: “The propaganda play ceases to be propaganda when it becomes good drama.”[39]

That the play only has “something of a communist bias” is an understatement; the play was written while Odets himself was a member of the Communist Party.[40] The play can not escape its Communist origins. One of the scenes depicts two actors discussing the Communist Manifesto. We know that this scene was performed by the Playhouse in 1936 because Gerard Van Steenbergen was cast as the actor.[41] A play that involves the sympathetic reading of such a document has more than a subtle Communist bias, which is why Ottenheimer’s idea of drama overpowering propaganda is so important. Not only was this a good defense for the Playhouse to take when facing charges of Communism, but the idea attempts to separate art from politics. However, the Playhouse itself did not differentiate between the two, and The Group Theatre believed that the art form of the play—incorporating audience participation—was by itself a political act. Lefty may have been the newest piece of avant-garde theatre to come out of New York, but it was played in a self-proclaimed community theatre, during a volatile time in Seattle’s history.

The backlash against the Playhouse for staging Lefty developed, as Florence James put it, when “Mr. Ottenheimer went to the Seattle Times with his news releases and was told, ‘We can’t accept anything from you until you talk to the Assistant Editor.’”[42] Though the paper had covered the maritime strike, it had labeled all labor activism as Communist in nature.[43]

The Jameses' political commitments and staging of progressive theatre came under attack with the red scare of the late 1940s. In Seattle's 1948 Canwell Committee hearings, the forerunner to naitonal McCarthyist hearings, the Jameses were charged with being Communists and the Seattle Repertory Playhouse was called a "Communist front: organization. Here, Florence James is forcibly evicted from the Canwell Committee hearings 1948 when her lawyer's request to re-examine previous witnesses was denied. Click on the photograph to read more about the Canwell Committee and Red Scare in Washington. (Image courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry photograph collection.)

Why would the paper refuse to publish an article about Lefty if they had covered the longshore strike? The difference seems to speak to Clurman’s description of the audience as “frenzied” at the first showing of Lefty.Art and culture could move people to action. So while scandals about city politics were newsworthy and entertaining, the applauding and advertising of Waiting for Lefty could be dangerous. Florence James argues that the Times’ reaction was due to the audience at the show, one that “came to the play in evening clothes” noting that when you “incite people in evening clothes to riot, you are really climbing into revolution.”[44] In confronting the Times about the blackout on the Playhouse, Mr. Ottenheimer discovered that they believed that socialist preacher Reverend Shorter had sold the tickets.[45] It should be noted, though, that the ticket committee, headed by UW professor N.J. Norrie, sold the tickets mostly to Playhouse subscribers, neither Shorter’s congregation nor working-class Seattleites.[46]

It then seems instructive to look at both the negative and positive feedback the theatre received in response to the showing. Mr. Ottenheimer only recorded letters of patrons that had positive feedback about Waiting for Lefty. Of the twenty-six letters recorded in the logs, eight were from university professors, marking the high percentage of professors in the audience.[47] Considering the backlash from the Seattle Times, it seems unlikely that the Playhouse only received letters of approval, even though Mr. Ottenheimer notes that “never, in all the history of The Playhouse, have we received so much mail praising a single production.”[48]

Ottenheimer’s report of favorable letters from the audience shows how it was those who didn’t actually see the performance thatwere most upset by it. Two groups, the Silver Shirts—a local fascist organization—and the King County Women’s Republican’s Club, were both were vocal in their protest of Lefty. The King County Women’s Republican Club noted that the play was “based on ideas and suggestions entirely un-American, and inclined to encourage subversive action,” and that they were advising the Playhouse board to enforce a greater degree of censorship on productions.[49] Through secondhand knowledge, Ottenheimer learned that “the Silver Shirts are after us” and believed that “our production of Lefty was paid for by Moscow Gold, Mrs. James having made arrangements for such on her trip to Russia summer before last… The Playhouse is a hot-bed of communism and sedition.” [50] While the Silver Shirts were a reactionary fascist group, the King County Republican women are not, and we cannot dismiss the uproar against Lefty as the ravings of a conservative radicals. In light of the recent maritime strike, it seems that there was a broader unease about the rising power of labor in Seattle in this period, and a fear that Lefty could inspire workers to action.

Though the play was successful in other cities, it acquired so much controversy and backlash in Seattle that it became too risky to the Playhouse to extend its run beyond a single night. While neither the Playhouse log books nor Fists Upon a Star directly state the reason that Lefty was not staged again, it can be surmised that the Playhouse came to the decision not to do another run from a Board meeting February 11, 1936 in which “a resolution passed unanimously that no special performances except of plays regularly on our schedule be given without the express authorization of the Board.”[51] The meeting, hardly a month after the showing of the play on January 12, was held in the midst of the Lefty hysteria.In addition, “the bulk of the criticism [about Lefty]… was apparently not directed against the play… but against the manner in which the performance was managed and the fact that the Board felt that it had not been taken completely into confidence.”[52] That Ottenheimer was aware the board might protest Lefty is undeniable. On June 15, 1935 Ottenheimer wrote in the Playhouse logs a reference to the petition for the play circulating at the University of Washington. Ottenheimer notes that he “told him [Norie] to do all he could to promote the petition if it came to hand, as it would be valuable in demonstrating to the Board the demand for such plays, if they should object, as it conceivable.”[53] The end result of Ottenheimer’s obvious concern with the Board’s perception of Lefty culminated in the February 11th Board meeting. In addition, and seemingly tied to the Board’s apprehension about the mishandling of the promotion for Lefty, was concern about to whom the Playhouse should be allowed to rent its space.[54] The Board’s strong concern and condemnation of how Lefty was promoted made it impossible for the play to continue running; but the Board’s concerns came within the larger context of conservative protest and reaction against the play.

The Importance of Waiting for Lefty in Seattle

The Jameses and the Seattle Repertory Playhouse were an integral part of the Seattle community. As patrons of the arts, the Jameses’ attempted to bring new dramas, along with the old, to Seattle’s public. Clifford Odets’s Waiting for Lefty was one such new drama. What was different about this play was its engagement with the social movements of the thirties and its attempt to incorporate the audience into that struggle. Waiting for Lefty talked about the issues that became of supreme importance during the Depression— food for the family, space of your own, racism, social alternatives—all presented in a way that asked the audience to engage with the issues themselves. For the Times and other political groups of Seattle, such as the King County Women’s Republican Club, Lefty was propaganda. For the Jameses and the theatre world, Lefty was an exciting revolution in dramatic arts because it broke the barrier between actor and audience. Florence James’s assertion that “Seattle was a very union-minded town then, and perhaps still is,”[55] explains why Lefty could appear so dangerous in a city that supported a flourishing new art school along with several other downtown Seattle theaters. A play that dared an audience to action was a play to be feared in a city where labor unions had just proven their power to close down the city and defy the police.

Lefty was also dangerous because it was more than propaganda or dramatic art. Lefty has to be understood within the dynamic history of labor in Seattle and in the context of the maritime strike of 1934 and the rising political prominence of labor leaders like Dave Beck and Harry Bridges. Waiting for Lefty caused a wave of either forcefully positive or negative response among the Seattle public. Waiting for Lefty provided a fraught arena in which labor politics could be studied and debated by the Seattle public, and in this way it succeeded in Odets’ aim: the audience truly did become engaged in the play’s struggle.

Copyright (c) Selena Voelker, 2010

HSTAA 498 Winter 2010

Works Cited

- Richard C. Berner, Seattle 1921-1940: From Boom to Bust (Seattle: Charles Press, 1992).

- Harold Clurman, The Fervent Years: The Group Theatre and the Thirties. (New York: Da Capo Press, 1983).

- Florence Bean James, Fists Upon a Star: Drafts for an autobiography (pre-1978), held in the Florence Bean James Papers, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Accession 2117.

- Seattle Repertory Playhouse manuscript collection, 1928-1950, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Accession 1481.

- Clifford Odets, Waiting for Lefty (New York: Dramatists Play Service, 1935).

- The Great Depression in Washington State Project, http://depts.washington.edu/depress/

- Ronald Oakley West, "Left Out: The Seattle Repertory Playhouse, Audience Inscription and the Problem of Leftist Theatre during the Depression Era" (Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis,-University of Washington, Seattle,1993.)

[1] Harold Clurman, The Fervent Years: The Group Theatre and the Thirties, (New York: Da Capo Press, 1983).

[2] “Playhouse Logs”, 1556-3, folder 5 pg. 341.

[3] Florence James, “Fists Upon a Star” drafts, Pg. 11.

[4] Sarah Guthu, “Florence and Burton James and the Seattle Repertory Playhouse,” Great Depression in Washington State Project, 2009, < https://depts.washington.edu/depress/theater_arts_james.shtml>.

[5] Florence James, “Fist Upon a Star”, drafts, pg. 28.

[6] “The Fervent Years”, pg. 12.

[7] “The Fervent Years”, pg. 117.

[8] “The Fervent Years”, pg. 118.

[9] “Waiting for Lefty”, pg. 31.

[10] “The Fervent Years”, pg. 147.

[11] “The Fervent Years”, pg. 148.

[12] “The Fervent Years”, Pg. 148.

[13] “Playhouse logs”, 1556-3, folder 5 pg. 340-1.

[14] “Seattle 1921-1940: From Boom to Bust”, Berner, pg. 293.

[15] Waterfront Workers History Project, http://depts.washington.edu/dock/34strike_intro.shtml.

[16] “Seattle 1921-1940: From Boom to Bust”, Pg. 346.

[17] “Fist Upon A star” notes, Florence James.

[18] “Fist Upon A Star” notes, Florence James.

[19] “Fist Upon A Star” notes, Florence James.

[20] “Fist Upon A Star” notes, Florence James.

[21] “Fist Upon A Star” notes, Florence James.

[22] Playhouse Logs, folder 6, pg. 339.

[23] Playhouse Logs, folder 5, pg. 300.

[24] Playhouse Logs, folder 5, pg. 327.

[25] Playhouse logs, fold 6, pg. 197.

[26] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 197.

[27] “Fist Upon A Star” draft, Florence James.

[28] “Fist Upon a Star” drafts, Florence James.

[29] Playhouse Logs, folder 6, pg. 21.

[30] The Great Depression in Washington State, “Florence and Burton James and the Seattle Repertory Playhouse”, Sarah Guthu, http://depts.washington.edu/depress/theater_arts_james.shtml.

[31] “Fists Upon a Star” drafts, Florence James.

[32] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 175.

[33] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 52.

[34] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 54, 186.

[35] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 60.

[36] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 92.

[37] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 179.

[38] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 186.

[39] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 188.

[40] Berry Witham, speech, Jones Playhouse, Seattle, 2/18/10.

[41] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 190.

[42] “Fists Upon a Star” drafts, Florence James.

[43] “Seattle 1921-1940: from boom to bust”, pg. 339.

[44] “Fists Upon a Star” drafts, Florence James.

[45] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 197.

[46] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 203.

[47] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg 124-225.

[48] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 205.

[49] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 250.

[50] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 214.

[51] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 256.

[52] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 256.

[53] Playhouse logs, folder 5, pg. 340.

[54] Playhouse logs, folder 6, pg. 256.

[55] “Fists upon a Star” drafts, Florence James.