Negro Repertory Company:

Stevedore

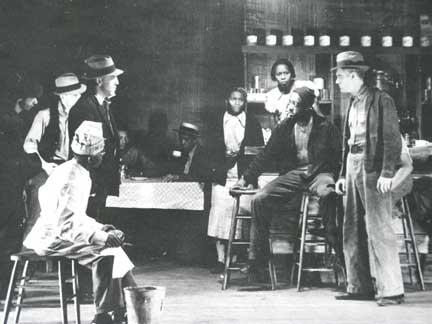

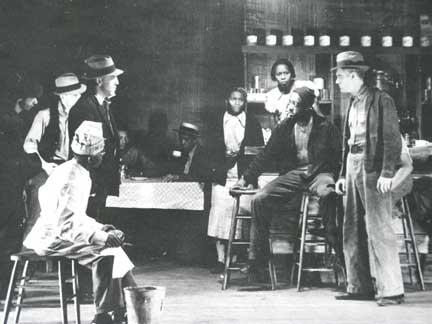

Stevedore's cast brought white and African American actors together in a play about the tenuous solidarity built during labor strikes. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection, (PH Collection #236), box 4, folder 18.)

When it was formed, the Negro Repertory Company may not have been considered a permanent adjunct of Seattle’s Federal Theatre Project. When Florence and Burton James at the Seattle Repertory Theatre made their contract agreement with Guy Williams, the assistant regional director of the Federal Theatre Project in Seattle, they only arranged to produce two shows—and had five months in which to do it. The NRC’s second production, Stevedore, in 1936, would win the young NRC national attention and respect and begin to change expectations for the group.

George Sklar and Paul Peter’s piece of labor agitation-propaganda (agit-prop) explored the confluence of class and racial prejudice. In the play, a white woman who threatens to expose her extramarital affair is beaten by her lover. Rather than reveal the truth—and her infidelity—the woman claims that a black man attempted to rape her. Police scour the city, picking up as many black men as they can, harassing them and putting them into lineups.

The blatant racism becomes a tool for Jeff Walcott, Superintendant of the Oceanic Stevedore Company, who manages to have his employee, Lonnie Thompson, arrested and put into a second lineup after Lonnie confronts Walcott for cheating his black employees out of some of their pay. Racial and class tensions mount as Walcott’s gang of hired thugs tries to attack Lonnie and a white member of Lem Morris’s union defects to Walcott rather than welcome Lonnie and his friends into the local branch. When Lonnie protests another groundless arrest, Walcott’s men try to kill him.

Though the black community doesn’t trust Lem Morris any more than any other white man, it’s Lem who gets Lonnie to safety as white mobs roam the streets, attacking black people and their properties. Ultimately, Lonnie argues, the community has to make a stand. As Walcott’s goons march to the black neighborhood in order to burn it down, Lonnie leads a resistance movement. The black residents build a barricade and resolve to fight. Though Lonnie is killed in the opening volleys between the two sides, Lem Morris arrives with his union workers in time to help the black community fight off their aggressors.

A scene from Stevedore. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection, (PH Collection #236), box 4, folder 18.)

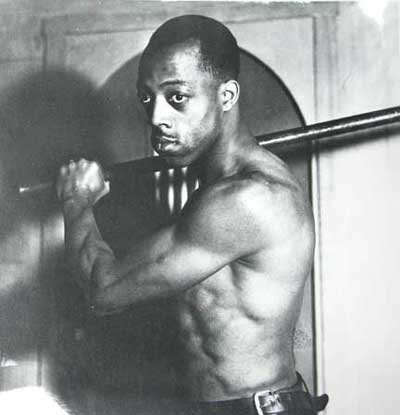

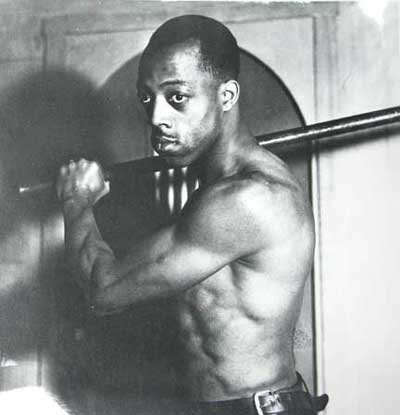

For her production, director Florence James added more music to the play. The chorus had been one of the most popular elements of the production of Noah she and Burton had staged in 1936. For Stevedore they added singing before every act, and employed the entire cast in song during the funeral scene. When casting, Florence utilized much from the Jameses’s very successful production of In Abraham’s Bosom. To play Blacksnake, James cast Joe Staton, who had been working up and down the West Coast. It was an important find for the Jameses, as Staton was a magnetic actor and stayed with the NRC, quickly emerging as a powerful lead for the company. However, even with such talented artists, it seems the Jameses still had to work hard to shape their new company into a professional performance group. Their work paid off: Stevedore was a hit.

The play so resonated with Seattle's audiences, who had experienced the 1934 longshore strike, that some members of the audience spontaneously joined the cast on stage to help build the barricades in the final scene. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection, (PH Collection #236), box 4, folder 18.)K

Seattle has always been a port city, and in 1934 had been an important site of the West Coast longshoremen’s strike. In short, Stevedore was a sensation in Seattle; it could not have been more relevant. Some members of Seattle’s small black community worried that the angry and aggressive laborers the play featured would frighten bourgeois whites and encourage racial stereotypes based on fear, but audience members kept coming—and coming back. One night, local dockworkers “bought out the show,” as Staton recalled. The night proved to be a stunning exemplar of Hallie Flanagan’s vision for the Federal Theatres: the theatre as a vivid, living, and relevant part of the community. When the call to arms came at the end of the play, the actors were astonished to find the Seattle longshoremen leaving their seats to join the actors onstage and help build the final scene’s barricade.

Joe Staton, who played the role of "Blacksnake" in the production, was one of the leading actors of the Negro Repertory Company. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection, (PH Collection #236), box 4, folder 18.)

Reviews were equally glowing. The Post-Intelligencer called the play “vital and virile” and “a knockout,” and praised the company for their talent and their ability to bring out the “tragedy, humour and passionate undertones” of the leading roles.

No wonder, then, that after Stevedore ran to 36 performances, the Jameses approached Guy Williams again, this time seeking permission to add the piece to their summer festival repertory. Williams agreed—on the condition that the Jameses commit to a third NRC production. The Seattle NRC was up and running. Stevedore (which the Jameses would reprise again the following year) and Natural Man would gain the NRC national attention and acclaim—and ultimately, Seattle’s Company would prove second only to the New York City Negro Unit in output for the FTP.

Copyright (c) 2009, Sarah Guthu