by Sarah Guthu

Burton James, right, in 1946, with workers for a "cultural survey" of Washington State, to determine what cultural activities residents engaged with. (Image courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry photograph collection.)Florence and Burton James were active theatre artists in New York City whose tastes tended toward those of the “art theatre” of the period. They were also outspoken proponents of their art’s social mission. Enticed to Seattle in 1923 by the promise of teaching positions at the city’s prestigious Cornish College of the Arts, the Jameses quickly established a reputation for doing good work with modern plays, with a commitment to the experimental “art theatre” of Ibsen, Chekhov, and Shaw. The Jameses would go on to play a crucial role in establishing the contemporary theatre scene in Seattle, as well as influencing the social and artistic productions of the regional branch of the Federal Theatre Project in the 1930s. Despite—or perhaps because of—their strong influence in Seattle’s alternative and progressive arts community, the Jameses were targeted in 1948 by the anti-communist Canwell Committee hearings and forced to give up their Playhouse and theater.

It was their artistic and political commitments that first ran the Jameses aground with the conservative Board of Directors at Cornish in their initial foray into Seattle’s theatre. An attempt in 1928 to produce Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author was shut down, and the Jameses took fire for the choice of a supposedly “immoral” play. Despite the Jameses’s protests—and that of influential people in Seattle’s theatre community, like University faculty member Glenn Hughes—the Board of Directors was unmoved. When their contracts expired that spring, the Jameses resigned. Fortunately, the talented couple remained in Seattle. Instead of returning to New York, the Jameses founded their own theatre company, the Seattle Repertory Company. In 1930, when Hughes was elected the head of the drama department at the University of Washington, he hired both the Jameses onto the staff: Burton as a technical director, and Florence as the director of the acting program. Also in 1930, an old tile house in the University District was converted into a theatre, which became the home of the Jameses’s work during the Depression. They called it the Seattle Repertory Playhouse, which still stands on the corner of University Way (“the Ave”) and 41st St. NE in the University District. After a renovation in 2009, the Playhouse was reopened as the Floyd and Delores Jones Playhouse and continues to operate as one of the University School of Drama’s three playing spaces.

Florence Bean James. Born in 1892, she came to Seattle in 1923 with her husband Burton to teach drama at Cornish School. (Image courtesy of the University of Washingon Special Collections Library)For the Jameses, the Seattle Repertory Company offered the opportunity to create a socially relevant theatre that would engage its surrounding community with artistic production. As they developed a repertory of modern classics, then, they also carefully included plays that addressed local social concerns. Hence, in 1930, when Florence directed and Burton starred in Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, the Jameses marketed their production specifically to Seattle’s Scandinavian community. It was a clever plan; Ibsen’s epic of Peer’s search for meaning and avoidance of responsibility in life, and the music composed by Edvard Grieg for the play, were Norwegian. Yet Peer Gynt was also a financial risk, and indicates something of the Jameses’s ambitions: considered by some to be “unstageable,” the unwieldy five-act script ranges geographically from Norway to North Africa, blending fantasy and dream seamlessly with reality. Writing in the 1890s, Ibsen’s script called for a stage technology that did not yet exist. The Jameses cut Ibsen’s script down from five acts to three and hired a small chamber group to perform Grieg’s music. The play was a hit. Audiences came from as far south as California, as far north as Canada, and east from Montana to see the show. Not only did the Jameses sell out their entire run of the production in 1929, they revived it four times, later that summer of 1929, and then again in 1936, 1939, and 1941.

The Jameses and the Playhouse were off to a good start. In 1931, a production of Goethe’s Faust played to over 10,000 audience members, and the Jameses dared to use a mixed cast—to popular acclaim—by using both African American and white actors in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. By 1932, they had their own locally recognized theatre, and had developed a subscription audience of over 20,000 people.

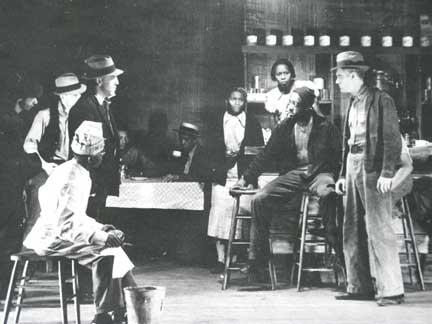

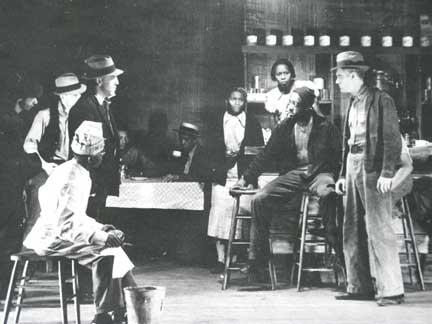

In 1933, the Jameses had another hit with In Abraham’s Bosom. This production was particularly important because it not only provided them another opportunity to work with Seattle’s African American community, but also fostered their relationship with members of Seattle’s African Methodist Episcopal Church. The Jameses’s work with the Church would lead to the creation of a Negro Repertory Company under the Depression-era Federal Theatre project, an undertaking that would later be used as proof of the Jameses’ communist sympathies when they were persecuted by “un-American” hearings in the 1940s. To produce In Abraham’s Bosom, a 1927 Pulitzer-Prize-winning play by Paul Green about an African American farmer whose attempts at self-improvement are thwarted by segregation, the Jameses recruited cast members from the choir of the local AME Church. The company proved so popular and the production so successful that the Jameses returned to this group of familiar faces when they began to compose the Negro Repertory Company troupe, casting their first production, Noah, largely from its ranks.

As the Depression continued and audiences dwindled, however, the Jameses became more radical in their politics and attempted to appeal to a poorer working-class audience and inspire them with plays about working people. In 1935 they offered a controversial production of Waiting for Lefty, Cliff Odets’s play about a union struggle and labor strike that involves audience participation, which was forcibly closed after only a single night.

Built in 1930, Seattle Repertory Playhouse was acquired by the University of Washington after the theatre closed in 1950. In 2009 it was remodeled and is now called the Floyd and Delores Jones Playhouse. (Image courtesy of University of Washingon Special Collections Library).Dwindling audiences and their proximity to the University itself also brought the Jameses into economic competition with Glenn Hughes in the School of Drama, one potential factor among many that led to the falling-out of Hughes and the Jameses. Florence would later attribute the breach to the Seattle Rep’s 1932 refusal to rent the Playhouse to Hughes for a University production of Ibsen’s Ghosts. Coming on the heels of the Playhouse success with Peer Gynt, the Jameses worried that Hughes’s production would be confused for a Seattle Repertory production by playgoers, and that if the production were successful it would weaken their ability to build a strong basis of financial support for their fledgling theatre company. Perhaps not surprisingly, Burton was let go from the University, though Florence would continue to teach until 1938. As the Playhouse developed its own acting school, the two theatres increasingly found themselves in competition not only for audiences, but for students. By 1934, Hughes, who had been on the original Board of Directors at the Seattle Repertory Playhouse, was no longer invested—literally—in the Jameses’s theatre efforts. That year, when the Playhouse’s bank note came up for annual renewal, Hughes refused to sign, citing that he was no longer on the executive board of the Playhouse and held differences of opinion.

As the Depression wore on and the Jameses searched for ways to continue to fund their theatre, they became interested in and eventually involved with the Federal Theatre Project, a national public works initiative that instituted regional theatres around the country as a way to mitigate the Depression-era unemployment in the arts. Originally, Burton James had attempted to compete with Glenn Hughes for the regional directorship of the project. Hughes, however, had the backing of the FTP national director Hallie Flanagan, and easily won the contest. However, Burton’s status in the community as a recognized theatre professional was useful to Hughes, who hired Burton to help him audition and construct the Federal Theatre Project’s company. Undaunted, the Jameses cast about for another way to be involved with the Federal Theatre Project, and proposed the formation of a Negro Unit at their theatre, a proposal both economically and ideologically attractive to the Jameses and to Flanagan, who happily endorsed the idea.

Though originally only contracted for two performances, the Jameses quickly realized the potential of the Negro Unit. Their first FTP production—Noah—was a popular success, reprised just months after its original production in the early spring of 1936. Their second production, Stevedore, which employed white and black actors in a play about a longshore strike, was so successful that the Jameses immediately sought permission to remount the production in their summer repertory theatre. Permission was granted, on the condition that the Jameses would produce an additional production with the Negro Repertory Company. The success of Seattle’s Negro Repertory Company was remarkable, particularly in city where the African American population hovered at 4,000 and never topped 5,000 and where racism continually undercut critical praise for the company. Racial politics inside of Washington’s FTP also created uneasy working conditions, as when the Seattle NRC was paired with a group of white actors from the Tacoma unit during the production of Power. In the face of these difficulties, the Negro Unit produced outstanding experimental and artistic theatre, gaining national acclaim for the Washington FTP and for the Jameses who hosted them.

Stevedore's cast brought white and African American actors together in a play about the tenuous solidarity built during labor strikes, and showcased the talents of the Negro Repertory Company. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection, (PH Collection #236), box 4, folder 18.)

Though perhaps never fully appreciated as a serious artistic venture, or as valued as their white counterparts, the Seattle Negro Repertory Company produced a string of outstanding pieces of theatre: Noah and Stevedore in 1936; the controversial production of Lysistrata later that year; Sinclair Lewis’ It Can’t Happen Here; a celebration of Paul Henry in Natural Man; and a final collaborative piece in 1938 produced by the troupe as a whole, An Evening with Dunbar. Originally slated for a mere two theatrical productions, the NRC was a sustainable and successful endeavor: though the Jameses sponsored the NRC only until 1937, the NRC was still working in 1939 when the plug was pulled on the Federal Theatre Project.

In addition to their commitment to the Negro Repertory Company and expanding Seattle’s theatre offerings to include its African American community, the Jameses expanded theatre audiences in Washington to include younger generations. The Washington State Theatre operated during the same years as the Negro Repertory Company (1936-1939), under the auspices of the Seattle Repertory Playhouse with funds from the Rockefeller Foundations. With this program, the Jameses brought theatre to high school students, many of whom had never seen a live theatrical production before. The Jameses toured state high schools, bringing performers to play to packed standing-room-only auditoriums. In rural areas, school buses were used to transport students from various towns to Washington State Theatre performances. Students were treated to both performances and to post-production talks with the actors, who would remain in costume for these post-performance discussions. Further commitment to education and artistic excellence led the Jameses to develop the first resident theatre school at the Seattle Repertory Playhouse in this period as well, which continued to strain relations with Glenn Hughes as the two training programs competed in the same neighborhood for the same student pool. In the beginning, the Jameses’s friends had joked that the Seattle Repertory Company was “a child they’d never be able to raise.” Year after year, as they celebrated the Playhouse’s anniversaries, the Jameses reminded the community of this joke and how patently wrong the predictions had been.

Florence James being forcibly evicted from the Canwell Committee hearings 1948. The Jameses were charged with being Communists, and their theatre, the Seattle Repertory Playhouse, with beinga "Communist front" organization. When her lawyer's request to re-examine previous witnesses was denied, Florence James protested, and was evicted from the courtroom and charged with contempt. (Image courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry photograph collection.)

The closure of the Federal Theatre Project removed financial support for the Negro Repertory Company, effectively ending its existence, and the Jameses' Washington State Theatre ended in the same year, 1939. Yet the Jameses continued to produce theatre in the 1940s and the early Cold War years, appearing never to allow the changing currents of politics and increasing culture of anti-communist suspicion to daunt their social idealism and pro-labor stance. In July 1948, the Jameses and Albert Ottenheimer (a UW alumnus who had served as press agent, actor, director and playwright with the Seattle Repertory over the years) were called before the Washington State Legislature’s Fact-finding Committee on Un-American Activities, a precursor to the more famous federal hearings. The Committee, led by Albert Canwell of Spokane, was investigating the influence of communism on the University of Washington campus. Forty professors were subpoenaed, though only eleven were ever called to testify. The Jameses and Ottenheimer were the only individuals called to account for themselves before this University investigation who were not members of the University faculty: Glenn Hughes had fired Burton sixteen years previously in 1932, and Florence ten years previously in 1938.

The testimony against the Jameses was thin. George Hewitt, the primary source of testimony on the Jameses, claimed that he had seen Florence in Moscow in 1932 and that she had been named by members of the Communist Party in Moscow as a contact in the Northwest. While it is true that Florence visited Moscow, she did not do so until 1934. Florence had visited the Moscow Art Theatre, certainly, but there is no evidence that she had visited the Comintern, as Hewitt claimed.

George Hewitt, an ex-Communist from New York, was the primary source of testimony for the Canwell Committee's charges against the Jameses, alleging that they were offficial members of the Communist Party. Hewitt is shown here testifying in Seattle. (Image courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry photograph collection.)

The Jameses’s response to this unsubstantiated attack was to refuse to recognize the legitimacy of the Canwell Committee. When asked the “sixty-four dollar question,” as it became known—“Are you or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?”—both Florence and Burton refused to answer on the grounds that the question itself violated their civil rights to freedom of political affiliation. Rather than being convicted of un-American activities, then, both were indicted for contempt of the Committee. With Ottenheimer and three University professors also cited for contempt for refusing to answer, the “Seattle Six,” as they became known in national headlines, fought through the legal system, trying to clear their names. When Florence’s trial came up in October, she and her lawyer made an aggressive attack on the Committee itself, accusing the system of prejudice and challenging its legitimacy, a tactic that nearly won her case. Florence’s jury debated for twenty-nine hours and ultimately was unable to bring a verdict. Unfortunately, Florence’s second trial in July of 1949 was not as successful and she was found guilty, fined $125, and given a thirty-day jail sentence, which was suspended. Burton was fined $250 and also given a thirty-day sentence, which was suspended on medical conditions shortly before his death.

The consequences for the Playhouse and the Jameses’s theatre company were dire. Subscribers dropped their subscriptions and the Jameses’s attempt to rally community support in a “Committee of 500” (each of 500 individuals sending $10 to help meet the theatre’s financial needs) was met with suspicion rather than support or patronage. The Jameses had sold their theater and were renting it when the new owner sold the space to the University of Washington. Some called it a coup, accusing Hughes of undercutting and buying out the competition. Before his death, Burton would accuse Glenn Hughes of “cultural vandalism,” but the University maintained that Hughes had strongly protested the acquisition. Nevertheless, the last production of the now-bankrupt Seattle Repertory Playhouse, Pygmalion, closed on December 30, 1950, and the University acquired the space. Burton died within eleven months, and friends attributed his rapid decline to a broken heart. Florence relocated to Saskatchewan, Canada, joining the Saskatchewan School of Arts as a drama instructor in 1953, and helping to found the Globe Theatre. She died in 1988, at the age of 95, highly acclaimed for her contributions to Canadian arts and theatre.

Copyright (c) 2009, Sarah Guthu

For a longer history of the Federal Theatre Project and the Seattle unit in particular, see Barry B. Witham, The Federal Theatre Project: A Case Study (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003).