Negro Repertory Company:

An Evening With Dunbar

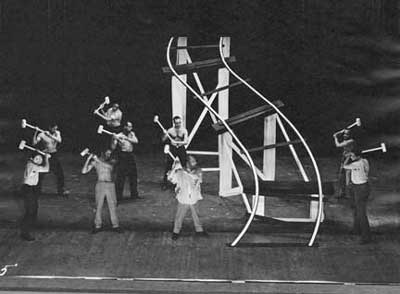

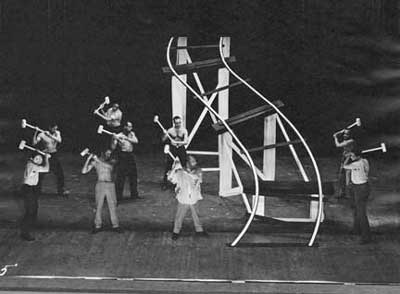

The Act II "work scene" from the Negro Repertory Company production of An Evening with Dunbar in Seattle, 1938. The gang is singing work songs and hammering with fluorescent-painted hammers. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection #236), box 4, folder 9.)

In late 1937, the future of the Negro Repertory Company was uncertain. After Esther Porter was transferred from the Company to run Hallie Flanagan’s Experimental Theatre at Vassar, the NRC unit was left without an official supervisor to direct its activities. Undaunted, the remaining twenty-three members of the NRC joined forces in the summer of 1938 and began to plan and collaboratively develop a new production based on the life of acclaimed African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar.

With only cursory supervision from Edwin O’Conner (the current director of the Federal Theatre Project in Seattle), Company members Joe Staton and Robert St. Claire stepped into leadership roles and guided the development of An Evening with Dunbar, while the company’s talented composer, Howard Biggs, wrote and orchestrated the musical score.

At first the Company planned to tell the story of Dunbar’s brief life (he died in 1906 from tuberculosis, at the age of thirty-three) as a narrative, but they soon discarded the idea as they found that the small Federal Theatre stage couldn’t accommodate their needs. Instead, the Company turned the spotlight on Dunbar and created an homage to the man and his work.

The Company developed a piece of theatre about the events of a small Southern community that could be depicted by thematic groupings of Dunbar’s poetry . Dunbar served as a kind of narrator, observing and commenting on the action, but not interacting with the other characters on stage. Led by Staton and St. Clair, the NRC set Dunbar’s poems to music and developed a loose framework to link the pieces together.

The party scene in Act III of An Evening with Dunbar, 1938. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection #236), box 4, folder 9.)

The production was truly collaborative. Staton continued revising the piece throughout its long rehearsal schedule over the summer and autumn of 1938 in order to incorporate each actor’s suggestions and discoveries made during improvisational work.

When the production finally opened, a list of members of the NRC was printed instead of the usual cast list. Dunbar was also well-researched. The Company chose to set their piece at the turn of the century, and to increase the authenticity of their presentation, they sought out “old-timers” in the community who could tell them about church behavior in the antebellum South, call-and-response singing on chain gangs, manners, and even dance steps.

The show opened and closed with choral numbers. The first scene, with a young, healthy Dunbar, featured wooing rivals and presented a glimpse of the religious life of the community. The second scene, with a visibly weaker Dunbar, took up the theme of work: as the lights came up for the scene centered on the poem Bucket Boy, the audience watched the cast swing hammers painted with bright fluorescent paint, referencing chain gang labor.

Joe Staton in Evening With Dunbar. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection #236), box 4, folder 9.)

After the song, brief dialogue segued to Dunbar’s The Letter. An announcement that “the boss” was returning quickly brought the cast back to work and working songs, as the lights slowly dimmed and died on their working bodies and bright hammers.

In the final scene, a feeble Dunbar read The Sum, a poem reflecting on work and life’s meaning. The cast dramatized Dunbar’s 200-line poem, The Party, incorporating two dance numbers and other poems translated to song, before closing the play with a recitation of Good Night to a dying Dunbar.

Staton found the work difficult to cast. As Dunbar didn’t limit the cast to the stereotypical roles “white” dramas of the period traditionally offered to black performers, Staton found the members of the Company overwhelmingly qualified to play many roles. The party scene was particularly well-suited to the NRC’s talents, and months of improvisation led to rich characterization and attention to detail in this ensemble production.

With high hopes for the production, Edwin O’Conner took a financial risk on the NRC and arranged for the production to run at the larger Metropolitan theatre in Seattle, instead of the FTP’s own smaller and less-frequented stage. With less than a month before opening, then, Staton and the NRC had to change their staging to accommodate the new, larger space.

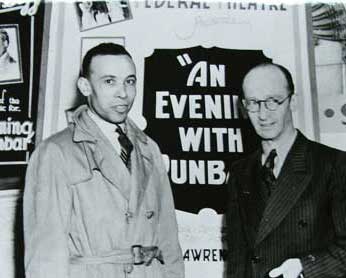

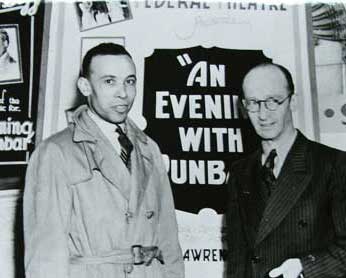

Urban League secretary Joseph Jackson, left, and unidentified man pose in front of the theatre during An Evening with Dunbar's run. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection #236), box 4, folder 9.)

Nevertheless, their hopes were not disappointed. Dunbar had the largest advance sales of tickets of any FTP production since the two companies had consolidated their operations the year before. Praise for the production was lavish, and though at times undercut by currents of racism, the ensemble cast and their new director were successes – and Howard Biggs, the company’s talented composer, finally won acknowledgment for his contributions to the unit.

Copyright (c) 2009, Sarah Guthu