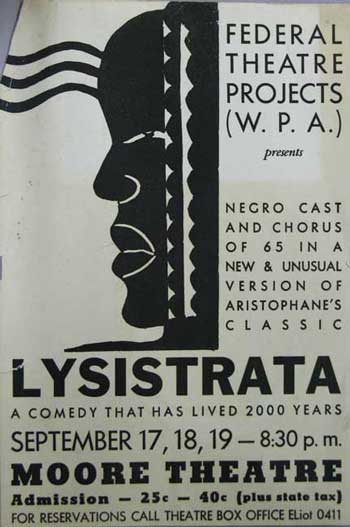

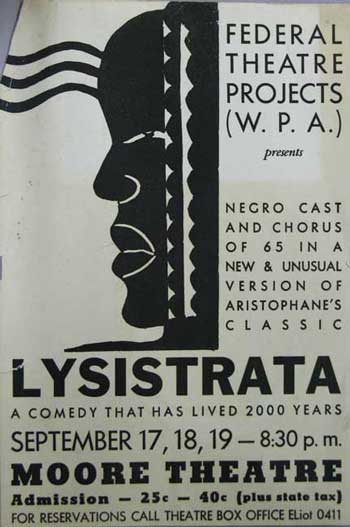

The Negro Repertory Company's production of Lysistrata produced a controversy between the national and local Federal Theatre Project leadership, and also displayed the paternalistic approach FTP officials held toward the Negro Repertory Company. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collections Division, Florence Bean James Papers, (accession # 2117-001) box 6, folder 11.)

The tenuous position of the Negro Repertory Company within the Seattle branch of the Federal Theatre Project, made all the more fragile by an ongoing power struggle between the Federal Theatre Project and the Works Progress Administration came to a head over their most famous and most humiliating production: Lysistrata. The Jameses hired company member Theodore Brown to adapt Aristophanes’ classical comedy, in which the women of Athens, Sparta, and Thebes unite to end the Peloponnesian war (a civil war fought between these three Greek city states).

In the play, the protagonist, Lysistrata, develops a two-pronged strategy toward the Greek men and their war-mongering. First, the women lay siege to and take possession of the Athenian treasury on the Acropolis, cutting the men off from funds needed to fuel their conflict. Secondly—and for which the play is famous—the women unite in a ban on sexual intercourse. They taunt and titillate their men, slinking around in scanty clothing, but refuse to satisfy the men’s desires until a peace is proclaimed—which, of course, it is.

Brown’s adaptation stayed close to the original script, with a few alterations. He added three choral numbers, which seem to have rapidly become one of the most popular features of Negro Repertory Company productions, to the play. He eliminated the lesbian homoeroticism in the script, where the women admire the beautiful body of a Spartan woman. And finally, Brown moved the action to Africa.

This last choice was perhaps a risky move, for though Orson Welles’s “voodoo Macbeth” was a great success in New York, the New York Living Newspaper project’s recent production of Ethiopia had been censored and rapidly shut down. Indeed, it is possible that Brown adapted Lysistrata to an African kingdom as a concession to his company’s inability to play Welles’s piece, rather than trying to ride the coattails of the New York production: the Negro Repertory Company had originally considered a production of Macbeth, but Brown believed that “they couldn’t handle it.”

All augured well for Lysistrata: scheduled for a three-day run at the prestigious Moore Theatre in downtown Seattle, advance ticket sales were brisk and the show opened on September 17, 1937 to a sell-out crowd of nearly 1,100 audience members. First night reviews were strong—the Seattle Star praised Brown for the “modern” update of the text, and the charm and humor that made for “an enjoyable evening in the theatre.” Surprisingly, the following afternoon, Lysistrata was closed—by the local Works Progress Administration.

The hierarchies of power between the Works Progress Administration and the Federal Theatre Project had never been clearly delineated. The two government institutions were supposed to function independently of each other, but in practice, the FTP frequently found itself subject to the WPA, which created both national and local frictions between both programs. Lysistrata served to solidify the independence of the Federal Theatre Project from the WPA, but unfortunately, the Negro Repertory Company’s production was sacrificed in the process.

The cast of Lysistrata. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collections Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection, (PH Collection #236), box 4, folder 13.)

Dan Abel, head of the WPA, had closed Lysistrata on the grounds that the play was bawdy and indecent, but without ever having seen it personally. Abel also attempted to establish himself as an official censor, who would read and approve all FTP production scripts before allowing them to be staged. The company was outraged, writing to FTP director Hallie Flanagan in New York for assistance. They claimed that Abel was discriminating against them, and trying to suppress their artistic achievement.

Hallie Flanagan and the employees of the Federal Theatre Project were livid. Four days after the closure, Hallie Flanagan’s National Administrator was assuring Guy Williams in Seattle that the Federal Theatre Project supported the Seattle NRC’s production one hundred percent, and five days after the closure, Flanagan’s assistant, Howard Miller, arrived in Seattle to settle the matter. The company, which continued to rehearse during the closure in hopes of reopening (indeed, Williams predicted that if the show could reopen, that it could easily run for four weeks), staged a rehearsal for Miller. Miller’s response, however, was negative.

Miller didn’t find the play offensive or bawdy; he claimed it was offensive in an adolescent kind of way, adding that any audience member who was familiar with vaudeville could not possibly be offended by the production. Miller did, however, criticize the production on other grounds, calling it “badly cast, badly directed, cheaply costumed,” and claiming it had “no focal point.”

A scene from Lysistrata. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collections Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection, (PH Collection #236), box 4, folder 13.)

When Miller met with Don Abel, the latter admitted that he had been in the wrong. However, Abel added that he could not reopen Lysistrata without needing to resign his position. Miller, in a gesture of conciliation between the FTP and WPA, agreed that Lysistrata should remain closed, on the condition that the WPA in Seattle finally relinquish control over the local FTP and stop trying to control the latter’s productions. Miller may have helped to smooth future relations between the FTP and WPA in Seattle through his negotiations, but the work of the Negro Repertory Company was buried in the process. Lysistrata was silenced in a single statement by a single man who not only had not ever seen the production, but was not even a member of the Federal Theatre Project itself.

Copyright (c) 2009, Sarah Guthu