by Catherine Roth

lynchingwwii111242-400.jpg)

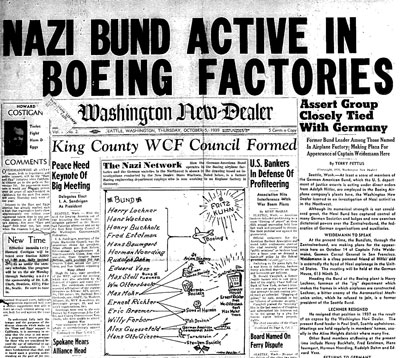

The WCF weekly newspaper, the New Dealer, often stressed the connection between Hitlerism in Europe and racism in America. This graphic is from November 12, 1942. excerpts from Roy's sociological survey.On July 25, 1941, Hugh DeLacy, the president of the Washington Commonwealth Federation (WCF), the left-wing caucus of the Democratic Party in Washington State from 1935–1945, wrote an impassioned letter to the Seattle Parks Board condemning the Board for the “denial of public bathing facilities to American children of the Japanese and Negro races” at Coleman Pool.[1] Less than a year later, however, the WCF’s cry for racial justice was absent upon the passage and implementation of Executive Order 9066, which resulted in the internment of Japanese Americans for the duration of America’s involvement in World War II.

The sharp contrast between the WCF’s forthright defense of Japanese American children in 1941 and its conspicuous silence surrounding the internment of Japanese Americans in 1942 is just one example that demonstrates the complexities of the organization’s stance on civil rights and race from 1935–1945. Although the WCF proclaimed itself a champion of civil liberties upon its conception, its commitment to the rectification of racial injustice and its promotion of civil liberties for racial minorities must be subject to the same critical analysis as the history of the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA). The WCF’s political and editorial advocacy of minority rights was—much like the CPUSA—consistently paired with anti-fascist or anti-imperialist rhetoric that preached a deep commitment to universal rights of all races on the grounds of defending democracy. This rhetorical component, inextricably linked to the WCF’s successful promotion of African American, Filipino American, Japanese American, and Chinese American civil rights, in conjunction with the organization’s silent consent of the Japanese American internment, reveals the WCF’s dedication to something deeper than pure racial justice. Below the surface of the WCF’s fight for minority rights lay the agenda of the Communist Party of the United States vis-à-vis the Soviet Union.

Background

More than 1,100 delegates attend 1940 Seattle convention of the Washington Commonwealth Federation. The WCF nominated candidates for state and local offices, functioning as a leftwing caucus within the Democratic Party. (February 8, 1940). Here is more about the WCF The Washington Commonwealth Federation (WCF) was a diverse organization that served as what historian Albert Acena called “a city party, the New Deal wing of the state Democratic Party, a bloc of state legislators, an anti-Fascist coalition and a People’s Front organization.”[2] It emerged in the wake of the Washington Commonwealth Builders, Inc. (CBI), an organization founded in 1934 by members of Technocracy, the Seattle Unemployed Citizens League, and other radical groups.[3] Modeled after Upton Sinclair’s End Poverty in California (EPIC) campaign, the CBI primarily aimed to influence the Washington Democratic party into passing a “production-for-use,” not for-profit, legislation that would take idle factories and farm lands and turn them into cooperatives. In autumn 1935, the organization, beset with debt, morphed into a larger, more inclusive organization: the Washington Commonwealth Federation.[4]

The WCF quickly proved to be a more effective delegate body than the CBI. By June of 1936, 514 reform, liberal, and activist groups, including Technocratic groups, the Youth Forum of Olympia, the People’s Advancement Club of Vashon, the Socialist Party, the Bellamy Club, the Share-the-Wealth Society, the Cooperative Commission Alliance, the Democratic Precinct Club, and the Washington State Veterans, had become WCF affiliates.[5] The single most influential affiliate over the years, however, proved to be the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA).

Although the CPUSA’s revolutionary agenda initially stood in contrast to the CBI’s radical reformist “production-for-use” legislation, the rise of fascism abroad in Germany, Italy, and Japan, as well as at home in organizations such as the Silver Shirts, the American Legion, and the Liberty League, lead the CPUSA to “drop its rigid sectarianism and soft pedal its revolutionary rhetoric,” according to Acena.[6] The local CPUSA embraced the Popular Front, a CP strategy born at the Seventh World Congress of the Comintern in Moscow in the summer of 1935 that promoted an alliance between all local communist parties and political reform groups in opposition to the rise of fascism. As the local chapter of the CPUSA curtailed its revolutionary agenda, it grew to view the WCF as an ideal organization to implement the Popular Front strategy.[7] By 1936, the WCF had lifted its initial ban on all organizations affiliated with the Communist Party, and as the CPUSA presence was progressively felt during the late 1930s, Howard Costigan, the founder of the CBI and the executive director of the WCF, grew increasingly cozy with the CPUSA.[8]

The Communist Party of the USA and Civil Rights

This woodcut from the Voice of Action, a Seattle weekly published by the Communist Party, shows the anti-racist agenda of the CP in the early 1930s. It accompanied a Feb 12, 1935 article about the Todd bill that would have banned mix-race marriages in Washington State. Click to read more on the Communist Party and its practices.. The involvement of Communists in the WCF is significant for numerous reasons; of particular interest here is how the Communists informed the WCF’s stance on civil rights. Since its conception in 1919, the CPUSA addressed the “race question” with ardor, particularly focusing on the status of African Americans. The Party argued that racial animosity and violence was caused by capitalists aiming to keep both black and white workers exploited and divided. Throughout the 1930s, the CPUSA’s “war on white chauvinism” resulted in the Party’s support of black candidates for office, admittance of Japanese American and African American members to the Party, and a commitment to challenging vigilante violence and institutionalized discrimination. The most commonly noted campaigns include the Scottsboro Boys defense in 1931 and the campaign to elect James W. Ford as Vice President in 1932. Earl Ofari Hutchinson, author of Blacks and Reds, notes that in the 1930s, “Communist Party members could rightfully boast that they broke American racial taboos.”[9]

The Party has been critiqued, however, for faithfully following the twists and turns of the Soviet Union’s policies—often times at the expense of racial minorities. As the CPUSA’s general program was revised in accordance to Popular Front policy, the Party simultaneously altered its strategy of defending the civil rights of racial minorities. After a decade of advocating self-determination for African Americans from a colonized “black belt” in the South, the CPUSA abandoned its revolutionary theory and rhetoric and focused, historian Wilson Record states, on the “immediate needs” of the African American community while simultaneously “directing” racial minorities into the “general united front camp against ‘war and fascism.”[10] The Party made a number of invitations to moderate African American organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Urban League (NUL) during the Popular Front, proposing combined action on pressing civil rights issues.[11] Though the Party was successful in creating the National Negro Congress and in winning key reforms, in analyzing Popular Front organizations like the WCF and the CPUSA’s editorial campaigns, we can see how the underlying policies of the Soviet Union were able to cloud the Party’s dedication to civil rights for racial and ethnic minorities.

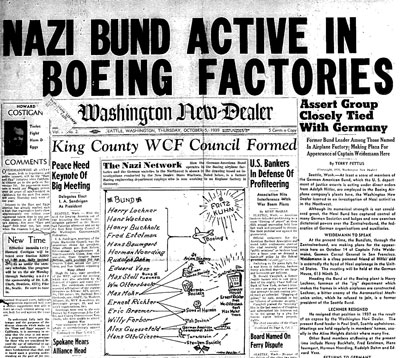

The Hitler-Stalin pact did not stop the New Dealer from exposing the dangers of fascism, as seen in this article from October 5, 1939. Click to enlarge.The Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of 1939 restricted the CPUSA’s practical interest in minority rights. The Pact, which allied the Soviet Union with Nazi Germany, compelled the CPUSA to drop its efforts to build a Popular Front with liberal and reformist organizations and instead focus its ire on American imperialism, labeling interventionists as “bureaucratic sell-outs” with aims to prevent the United States from entering an “imperialist war.”[12] Again, the overarching policy shift required a revision of the CPUSA’s strategy of defending minority rights. Abandoning the progress made with organizations such as the NAACP and the NUL, the Party instead asserted that these organizations were “paid agents of the Roosevelt administration, whose job was to line up… support for the ‘imperialist war.”[13] During the Nazi-Soviet Pact years, the CPUSA carried on an intensive anti-war propaganda campaign; this campaign was reflected in its minority rights crusade. The CPUSA reinstated the self-determination doctrine for African Americans, as they again “became a nation under the heel of American imperialism.” The Party additionally insisted that the “rights of racial minorities were not involved in the European war” and that they should not support the Allied nations or the United States in the war effort.[14]

The Hitler-Stalin pact did not stop the New Dealer from exposing the dangers of fascism, as seen in this article from October 5, 1939. Click to enlarge.The Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of 1939 restricted the CPUSA’s practical interest in minority rights. The Pact, which allied the Soviet Union with Nazi Germany, compelled the CPUSA to drop its efforts to build a Popular Front with liberal and reformist organizations and instead focus its ire on American imperialism, labeling interventionists as “bureaucratic sell-outs” with aims to prevent the United States from entering an “imperialist war.”[12] Again, the overarching policy shift required a revision of the CPUSA’s strategy of defending minority rights. Abandoning the progress made with organizations such as the NAACP and the NUL, the Party instead asserted that these organizations were “paid agents of the Roosevelt administration, whose job was to line up… support for the ‘imperialist war.”[13] During the Nazi-Soviet Pact years, the CPUSA carried on an intensive anti-war propaganda campaign; this campaign was reflected in its minority rights crusade. The CPUSA reinstated the self-determination doctrine for African Americans, as they again “became a nation under the heel of American imperialism.” The Party additionally insisted that the “rights of racial minorities were not involved in the European war” and that they should not support the Allied nations or the United States in the war effort.[14]

After Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, the position of the CPUSA flipped again, as the Soviet alliance with Germany crumbled. The Party joined what became the Second Popular Front campaign and argued that war was necessary for “national liberation, for survival, and for the preservation of the democratic institutions of people all over the globe.”[15] Again the “race question” was revised as the CPUSA asserted that the “struggle for the rights of the Negro people [was] an inseparable part of the struggle against fascism and reaction.”[16] During the pro-war years, the CPUSA again abandoned the doctrine of self-determination for African Americans and focused on achieving basic rights for racial and ethnic minorities, particularly focusing on cases of discrimination in the war industries and the armed forces.[17] Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Party’s adamant pro-war stance led the CPUSA to expel their Japanese American members as well as support the internment of Japanese Americans.[18]

The Washington Commonwealth Federation and Civil Rights

Similar to the CPUSA, the Washington Commonwealth Federation’s proclaimed commitment to minority rights requires careful analysis. Largely silent on issues of race throughout the 1930s, it was not until the Second Popular Front formed in 1941 that the WCF took an active interest in issues pertinent to racial minorities, doing so through its influence on state politics and through editorials in its organ (The Sunday News from 1936–1938, The Washington New Dealer from 1938–1943 and The New World from 1943–1945.) The WCF’s enthusiasm for minority rights, however, dripped with grandiose and sensational anti-fascist or anti-imperialist rhetoric that mirrored the CPUSA’s agitprop style and took away from the personal and practical issue at hand. As historian Albert Acena states, the WCF used civil rights as a “rubric” to keep watch for fascist activities.[19] This is demonstrated in three periods of change that coincide with the alteration of CPUSA’s agenda.

The Formative Years, 1935–1937

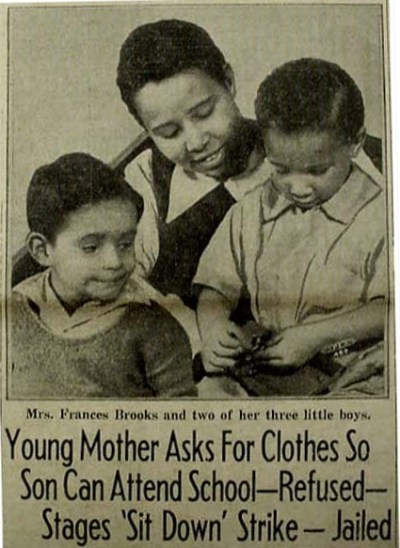

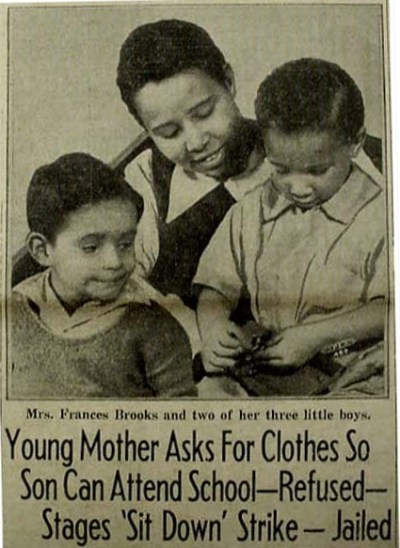

Mrs. Francis Brooks became a relief-struggle celebrity after losing her job with the Negro Federal Theatre Project as a result of funding cutbacks. Arrested for her relief office "sit down strike," she received an outpouring of sympathy. A delegation of 26 women from the Washington Commonwealth Federation attended her court hearing. Sunday News February 14, 1937The WCF paid little heed to minority civil rights cases in its formative years. The most prominent example that reveals the peripheral status of minority rights occurred in March of 1935, as the CBI was beginning its transformation into the WCF. John Scott, an eighteen-year-old African American male who was accused of raping a thirteen-year-old white female, was subjected to police beatings and was threatened with lynching unless he confessed to the rape. The local NAACP, drawing a connection to the famous Scottsboro case, raised a defense fund of $300 to support Scott.[20] Though the NAACP eventually dropped the case because it was “not meritorious enough,” the potential for Scott’s case to become the “Pacific Northwest Scottsboro Case” was never acknowledged by the CBI/WCF. Indeed, during the period from 1935–1937, the CBI/WCF chiefly focused on workers’ rights, largely limiting its civil rights work in 1936 to “repeal[ing] the criminal syndicalism law, a labor code, probation of city gag ordinances, and legislation to keep state police on highways.”[21] The platform formulated at the 1936 convention committed the WCF to the “full protection of civil liberties to preserve…democratic rights and to ward off the threat of fascism.”[22] The platform, though lacking a commitment to minority rights, reveals the WCF’s early pairing of civil rights with anti-fascism. This pairing can be found in all the WCF’s advocacy for civil rights up until the Nazi-Soviet Pact in 1939, revealing a close connection to the CPUSA’s agenda and policies.

Mrs. Francis Brooks became a relief-struggle celebrity after losing her job with the Negro Federal Theatre Project as a result of funding cutbacks. Arrested for her relief office "sit down strike," she received an outpouring of sympathy. A delegation of 26 women from the Washington Commonwealth Federation attended her court hearing. Sunday News February 14, 1937The WCF paid little heed to minority civil rights cases in its formative years. The most prominent example that reveals the peripheral status of minority rights occurred in March of 1935, as the CBI was beginning its transformation into the WCF. John Scott, an eighteen-year-old African American male who was accused of raping a thirteen-year-old white female, was subjected to police beatings and was threatened with lynching unless he confessed to the rape. The local NAACP, drawing a connection to the famous Scottsboro case, raised a defense fund of $300 to support Scott.[20] Though the NAACP eventually dropped the case because it was “not meritorious enough,” the potential for Scott’s case to become the “Pacific Northwest Scottsboro Case” was never acknowledged by the CBI/WCF. Indeed, during the period from 1935–1937, the CBI/WCF chiefly focused on workers’ rights, largely limiting its civil rights work in 1936 to “repeal[ing] the criminal syndicalism law, a labor code, probation of city gag ordinances, and legislation to keep state police on highways.”[21] The platform formulated at the 1936 convention committed the WCF to the “full protection of civil liberties to preserve…democratic rights and to ward off the threat of fascism.”[22] The platform, though lacking a commitment to minority rights, reveals the WCF’s early pairing of civil rights with anti-fascism. This pairing can be found in all the WCF’s advocacy for civil rights up until the Nazi-Soviet Pact in 1939, revealing a close connection to the CPUSA’s agenda and policies.

The Popular Front Years, 1937–1939

As the Popular Front years advanced and as the CPUSA influence on the WCF grew stronger, the WCF took an increased interest in issues of racial injustice. By 1938, the WCF had expanded its position on civil rights in its constitution to include the “protection of the rights of workers to organize, strike, picket and bargain collectively; protection for the rights of all social, racial, religious, and economic groups; and protection of the rights of teachers to teach in accordance with their knowledge and convictions” [emphasis added].[23] This interest was reflected in a number of cases, namely the defeat of House Bill 301 and the defense of Berry Lawson.

The WCF is credited for assisting in the defeat of House Bill 301, an anti-intermarriage bill first proposed in the state legislature in February of 1935 that, if passed, would “prohibit the marriage of persons of Caucasian ancestry to Negroes, Orientals, Malays and persons of Eastern European extraction.”[24] Though the WCF paid no heed to the bill in 1935, when a second anti-interracial marriage bill was introduced in 1937, the WCF joined the multiracial coalition of whites, blacks, and Filipinos that fought and defeated the measure.[25] Though Acena argues that the WCF’s role in the defeat was overstated (particularly in The Sunday News), that the organization used its influence on state politics to assist a multiracial coalition working to defeat a racially discriminatory measure reveals one way that the WCF defended racial minority rights in the spirit of the Popular Front. [26]

The NAACP's prosecution of three Seattle policemen accused of killing an unarmed African American man, Berry Lawson, was a watershed for civil rights cases during the Depression. Here, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reports on the case, April 8, 1938. Click to read about the Lawson case. The largest racial justice case that the WCF took interest in during the Popular Front period was that of Berry Lawson, a twenty-one-year-old African American transient hotel waiter who died after a severe and unjustified beating by three police officers in the spring of 1938. In reaction to the murder, the African American community organized a “committee of community representatives” including Republican, Democrat, and Communist men and women. In the spirit of the Popular Front, the WCF joined this campaign to take on the issue of police brutality, increasing the exposure of the case in numerous articles in The Sunday News. The WCF did not just follow the case to its conclusion when the three police officers were charged, however. An article titled “Negroes, Angered at Lawson Death, Demand End of Police Brutality” quoted Carl Brooks, an African American affiliate of the WCF, stating that the brutal tactics of the policemen who murdered Lawson “[could] only lead to fascism.”[27] The WCF, in accordance with the CPUSA’s agenda to thwart the rise of fascism, persisted in tying civil rights violations to fascist tendencies.

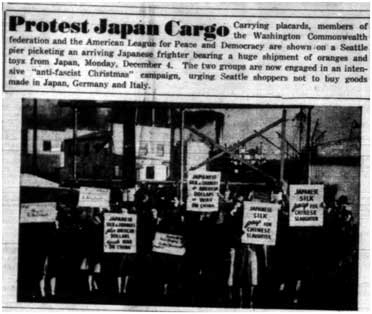

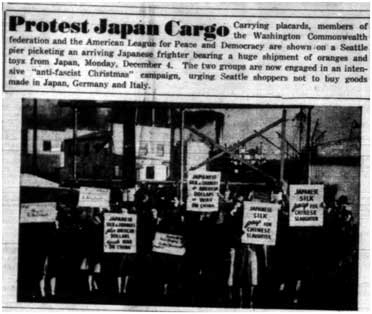

The front page of the Sunday News, the Washington Commonwealth Federation's newspaper, called for a boycott of Japanese goods in protest of the Japanese empire's attacks on China, and was influenced by the Communist Party's anti-fascist political orientation in 1938. The Sunday News called it here an "anti-fascist Christmas campaign," urging boycotts on Japan, Germany, and Italy. This photograph is from December 17, 1938. Click to read more about the boycott. A further example of how the WCF’s pro-civil rights, anti-fascist campaign mirrored the CPUSA’s policies can be seen in the WCF-led boycott against Japanese-made goods, beginning in 1937. The boycott, part of a larger national movement supported by the CPUSA, aimed to “unload the aggressor’s guns” by ending the Japanese invasion of China. [28] The boycott was successful—by the end of December 1937, there was a reported $800,000 shrinkage in Japanese imports in Seattle alone, the “chief sufferers” being novelties, toys, porcelain and crockery.[29] The WCF ran an article in The Sunday News to remind readers that “boycotting goods made in Japan [did] not mean boycotting friends and neighbors and good citizens.” The WCF’s condemnation of bigotry towards citizens’ Japanese American neighbors, however, was not written purely out of concern for Japanese American citizens, but also revealed a deeper interest in thwarting the spread of fascism. The article goes on to state that condemning Japanese Americans as part of the boycott would force them to rely on Japanese, and not American protection, strengthening support for the “fascist” Japanese empire: “to boycott them [would] drive them… into dependence upon Japan.”[30] This continued pairing of civil rights violations with fascism portrays the WCF’s alternative motive in its constitutional commitment to protecting the “ rights of all social, racial, religious, and economic groups.”

The Nazi-Soviet Pact Years, 1939–1941

Though all-inclusive constitutional dedication to civil rights developed by the WCF during its Popular Front years remained in the constitution until the organization’s disbandment, the WCF’s promotion of civil rights continued to fluctuate in conformity with the CPUSA’s ever-changing stance on race and civil rights. During the era of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact from 1939–1941, the WCF became engaged in anti-war, anti-imperialism campaigns similar to the CPUSA, declaring in The Washington New Dealer that it would “aid labor, farmers, and all progressive forces in America to throw across the road to war a blockade for peace, an unyielding barrier of the common people.”[31] The WCF’s proclaimed goals during the Nazi-Soviet Pact years were revised suddenly to “eliminate profits from war, a new social security, new economic justice, better housing, adequate old age pensions, public medicine, equal educational opportunity, federal insurance, jobs for the unemployed, and civil rights for all.” [32] The WCF civil rights campaigns during this period predominately focused on workers’ rights, particularly the right to free speech and the right to organize, again largely ignoring matters of racial justice.[33] When the WCF did concern itself with minority rights, the focus was largely on national cases of discrimination and nation-wide movements that reflected the new anti-imperialist stance. Indicative of this stance was an article published just months before the German invasion of the Soviet Union that detailed the coalition of 160 of the “most outstanding artists, educators, churchmen, and professionals among the Negro people” who in early June of 1941 signed a statement that “branded both sides of the war imperialistic, anti-Negro and anti-Democratic” and claimed that Jim Crowism fueled the “war drive.”[34] The neglect of local issues of racial discrimination and violence as well as the commitment to the CPUSA’s new anti-war agenda led the WCF to the same critique as the CPUSA: the Washington Commonwealth Federation’s twists and turns in its minority rights advocacy exhibits an agenda-driven nature that often overlooked the personal and practical issue of racial violence and discrimination that existed in Washington state before and after the Nazi-Soviet Pact period.

The World War II Years, 1941–1945

The New Dealer condemned employment discrimination in this Feburary 26, 1942 article. Click to enlarge. Perhaps the best examples of how the WCF’s stance on civil rights and racial justice fluctuated in accordance with the CPUSA can be seen during the World War II years. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in late June of 1941, the WCF, true to its ties to the CPUSA, quickly revised its anti-war, anti-imperialism stance to adamantly encourage aid to the Soviet Union in its war against Hitlerism. Soon after, the WCF joined in the Second Popular Front effort to defeat fascism at home and abroad, and its interest in instances of racial injustice increased dramatically during the Second Popular Front period. Like the CPUSA, the WCF focused on instances of discrimination in the war industry and watched for opportunities to link racial injustice to “fascist” activities that aided the Axis.

The New Dealer condemned employment discrimination in this Feburary 26, 1942 article. Click to enlarge. Perhaps the best examples of how the WCF’s stance on civil rights and racial justice fluctuated in accordance with the CPUSA can be seen during the World War II years. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in late June of 1941, the WCF, true to its ties to the CPUSA, quickly revised its anti-war, anti-imperialism stance to adamantly encourage aid to the Soviet Union in its war against Hitlerism. Soon after, the WCF joined in the Second Popular Front effort to defeat fascism at home and abroad, and its interest in instances of racial injustice increased dramatically during the Second Popular Front period. Like the CPUSA, the WCF focused on instances of discrimination in the war industry and watched for opportunities to link racial injustice to “fascist” activities that aided the Axis.

While in June of 1941 the WCF was running articles about how the war drive in the United States was imperialistic and anti-democratic, just a month later, articles in The Washington New Dealer began attacking Nazi Germany once again, with a renewed support for defeating Nazism abroad and at home. In July, Hugh DeLacy and the WCF joined with the NAACP, Christian Friends for Racial Equality, and University of Washington black students to challenge the Parks Board’s discrimination against African Americans and Japanese Americans at Seattle’s Coleman Pool, arguing that the ban was “flagrantly un-American and so nearly akin to the vicious and equally unfounded racial theories of Hitler Nazi thugs.”[35] The bombing of Pearl Harbor in December of 1941 and the United States’ official entrance into World War II enhanced the urgency and frequency of the WCF’s involvement in racial justice campaigns.

If the Berry Lawson case represented the WCF’s interest in local, progressive challenges to racial injustice during the first Popular Front in the 1930s, the case of William Thompson reveals the WCF’s renewed interest and involvement by 1943. William Thompson was an African American war worker who was, like Lawson, brutally and unjustifiably beaten by police officers after an unwarranted arrest. The New World, the WCF’s organ in 1943, cited the case as the “most shocking attack on Negro people since Berry Lawson.” The New World editorial advocated the firing of the police officers, calling their actions “a crime against our nation fighting for its life against a savage foe.”[36] In addition to numerous editorials following up on the Thompson case, the WCF mailed the Mayor of Seattle a copy of President Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 Executive Order 8802, which prohibited discrimination in defense industries.[37]

Housing terror was more than a "little nasty." WCF and Communist Party activist Carl Brooks and his family were driven out a Lake City area neighborhood when their house was destroyed in this attack. New Dealer March 6, 1941. (Click to enlarge)Further examples of this increased activism for African American civil rights can be seen in the WCF’s challenges to the casual discriminatory practices that historian Quintard Taylor refers to as the “little nasties,” which “[served] to remind African Americans of their inferiority in an overwhelmingly white city.”[38] Like the CPUSA, the WCF took on cases of racial discrimination in the defense industries. On May 20, 1943, The New World reported an attempt to “provoke racial warfare” on the job at the Pacific Car & Foundry Company. The newspaper duly noted that “the person or persons who [sought] to create discord on the production front [were] consciously or unconsciously siding with the enemy…this itself [helped] Hitler.”[39] The WCF challenged housing discrimination as well, confronting Charles Ringer, a captain and air raid warden who, according to The New World, circulated petitions in opposition to the integration of African Americans in the Holly Park housing project that was funded by the federal government. Branding Ringer an “enemy of Democracy,” the New World campaigned for his removal, which the Seattle Mayor conceded to.[40]

Housing terror was more than a "little nasty." WCF and Communist Party activist Carl Brooks and his family were driven out a Lake City area neighborhood when their house was destroyed in this attack. New Dealer March 6, 1941. (Click to enlarge)Further examples of this increased activism for African American civil rights can be seen in the WCF’s challenges to the casual discriminatory practices that historian Quintard Taylor refers to as the “little nasties,” which “[served] to remind African Americans of their inferiority in an overwhelmingly white city.”[38] Like the CPUSA, the WCF took on cases of racial discrimination in the defense industries. On May 20, 1943, The New World reported an attempt to “provoke racial warfare” on the job at the Pacific Car & Foundry Company. The newspaper duly noted that “the person or persons who [sought] to create discord on the production front [were] consciously or unconsciously siding with the enemy…this itself [helped] Hitler.”[39] The WCF challenged housing discrimination as well, confronting Charles Ringer, a captain and air raid warden who, according to The New World, circulated petitions in opposition to the integration of African Americans in the Holly Park housing project that was funded by the federal government. Branding Ringer an “enemy of Democracy,” the New World campaigned for his removal, which the Seattle Mayor conceded to.[40]

Additionally, the WCF editorialized and campaigned to ease the plight of the Chinese under attack by Japan. Washington Congressional Representative and WCF affiliate Warren G. Magnuson led the 1943 campaign in Washington D.C. to lift a sixty-year-old ban against Chinese immigration to the United States. Citing the inability of the U.S. to extend military aid to allied China, proponents argued that the repeal of the legislation was the “least that [could] be expected.”[41] The repeal of the discriminatory ban on immigration, framed in terms of war alliances, further revealed that the WCF’s support of minority rights in this period was predominantly based on the principles of anti-fascism and democracy.

Moreover, the Cannery Workers’ WCF affiliate campaigned for the passage of the Randolph Bill in 1943, which would grant full citizenship rights to Filipinos. A. E. Harding, the International Representative of the United Cannery Agricultural Packing and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA) wrote a letter to Senator Thomas Rabbitt, the Washington State Senator and executive secretary of the WCF, who supported the Randolph Bill. Stating that “the majority of the men who fought in Bataan were Filipinos, not white Americans as is the general assumption,” Harding employed war rhetoric to convince Rabbitt that Filipinos deserved citizenship.[42]

Even in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the WCF appeared committed to defending innocent Japanese Americans by providing editorial space in The Washington New Dealer for Japanese Americans to pledge their allegiance to America. The New Dealer featured an article by James Y. Sakamoto of the Japanese American Courier titled “Japanese-Americans Loyal to the U.S.,” in which he stated, “…There are certain fundamental truths from which we cannot depart. One of them is that we were born in these United States as American citizens.”[43] The WCF also addressed the rising prejudice against Japanese Americans in a response to an opinion piece published in The New Dealer. When William Gibson of Vancouver, Washington wrote in to state, “If… an alien cannot be a citizen, then their offspring should not become a citizen by birth,” The New Dealer wrote in response, “The New Dealer has and will continue to be ‘pretty strong’ for the plain people of every land in the struggle against Fascism… [T]here is a big difference between opposing the repressive governments of Japan, Italy and Germany and taking reprisals against the Americans of those racial extractions.” Another article titled “Fascism and Racism” reminded readers that the war was not a “Racial War,” stating that “as never before, all patriotic Americans must guard against any type of racist angle being given our present national policy. The enemies are, as never before, Fascism and its ally, Racism.”[44]

The editorial defense of American citizens of Japanese descent, however, did not reach fruition in legislative action. As Japanese Americans were relocated to incarceration camps across the Western interior, the Washington Commonwealth Federation remained conspicuously silent, much like the CPUSA. On April 1, 1942, The New Dealer stated in a minuscule article on the third page that 225 Japanese had been “smoothly” evacuated from Bainbridge Island.[45] On February 17, 1942, The New Dealer ran an article entitled “Our Enemy Aliens.” The article promoted James Sakamoto’s accommodationist approach to the relocation, saying, “…this is war. There is no use getting panicky. They must obey.”[46] These two articles expose the WCF’s interpretation of and collusion with Japanese American internment: it was not a breach in civil rights but a wartime necessity. This pro-war stance, in blinding disregard of an egregious breach of civil rights, once again highlights how the WCF’s advocacy for civil rights of “all races” was overwhelmed by the agenda of the CPUSA vis-à-vis the Soviet Union.

Conclusion

Though constitutionally the Washington Commonwealth Federation proclaimed itself a defender of civil rights for all “social, racial, religious, and economic groups,” the twists and turns of its interest in and defense of minority rights raises questions about its sincerity and potential motives. There is, of course, no denying the legislative and editorial accomplishments of the organization in its civil rights advocacy—the WCF was one of the few predominately white organizations in Washington State willing to take on issues of inequity and racial discrimination and violence. Its alliance with organizations such as the NAACP and its admittance of the Filipino Cannery Union to the WCF, as well as its defense of individuals like Berry Lawson, William Thompson, and of Japanese American and African American children during the 1930s and 1940s demonstrates a true commitment to civil rights and racial equality.

However, the WCF’s support for the internment of American citizens of Japanese descent, while concurrently advocating for civil rights, must be analyzed. The rhetorical patterns and political phases of the WCF’s minority rights advocacy consistently matched the changing policy of the Communist Party of the United States. From the WCF’s intense Popular Front anti-fascist campaigns to the blindingly patriotic advocacy for U.S. involvement in World War II, it is clear that the WCF was not completely genuine in its promotion of racial justice. More often than not, the WCF followed the twists and turns of the CPUSA, using minority rights and civil rights issues advantageously to advance whatever cause was pertinent to the Soviet Union.

Copyright (c) 2009, Catherine Roth

HSTAA 353 Spring 2009

[1] Hugh DeLacy, letter to Parks Board. Robert E Burke Collection, Special Collections, Suzzallo Library, Seattle, Washington. Box 3, Fol. 28.

[2] Albert Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front, University of Washington Diss, 1975, abstract.

[3] Harvey Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism: The Depression Decade (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 253.

[4] Background information largely gathered from Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation; Klehr, Heyday, pp. 253-54.

[5] Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union Local 7 Records, Special Collections, Suzzallo Library, Seattle, Washington. Box 34; Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation, 91, 123.

[6] Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation, 101.

[7] Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation, 101-102.

[8] See Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation.

[9] Earl Ofari Hutchinson, Blacks and Reds: Race and Class Conflict 1919-1990 (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1995), 2.

[10] Wilson Record, The Negro and the Communist Party (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1951), 130-131.

[11] Record, The Negro and the Communist Party, 186.

[12] Record, The Negro and the Communist Party, 186.

[13] Record, The Negro and the Communist Party, 186.

[14] Record, The Negro and the Communist Party, 187, 188.

[15] Record, The Negro and the Communist Party, 209-210.

[16] James W. Ford, as quoted in Record, The Negro and the Communist Party, 212.

[17] Record, The Negro and the Communist Party, 213-215.

[18] Fred Wei-han Ho and Bill V. Mullen, eds, Afro-Asia: Revolutionary Political and Cultural Connections Between African Americans and Asian Americans (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 166-168, 189.

[19] Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation, 396-7.

[20] Quintard Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994), 93.

[21] The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) November 15, 1936.

[22] Platform, 1936. Robert E Burke Collection, Special Collections. Box 1, Fol. 2.

[23] Constitution, 1938. Robert E Burke Collection, Special Collections. Box 1, Fol. 2.

[24] Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community, 93.

[25] Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community, 94, 265.

[26] Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation, 154.

[27] “Negroes Angered at Lawson Death Demand End of Police Brutality,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA), April 1938.

[28] “Hundreds March in Everett Japanese Boycott Parade,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA), February 5, 1938.

[29] “Boycott Shrinks Japan Shipments Via Seattle $100,000 Monthly,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA), February 12, 1938.

[30] “Boycott and Race Prejudice,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA), Jan 19, 1938.

[31] “WCF Convention Call,” The Washington New Dealer (Seattle, WA), December 14, 1939.

[32] “WCF Convention Call,” The Washington New Dealer (Seattle, WA), December 14, 1939.

[33] See The Washington New Dealer, September 1939–June 1941.

[34] Jim Crowism Flourishing in War Drive, The Washington New Dealer (Seattle, WA), June 5, 1941.

[35] Robert E. Burke Collection. Box 3, Fol. 28; Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community, 168.

[36] “Police Slug Negro War Worker,” The New World (Seattle, WA), June 10, 1943.

[37] “Probing Beating of Negro Worker,” The New World (Seattle, WA), July 1, 1943.

[38] Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community, 80.

[39] “Racial Warfare Rapped,” The New World (Seattle, WA), May 20, 1943.

[40] Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation, 39; “Remove the Negro-Baiter,” The New World (Seattle, WA), June 17, 1943.

[41] “Ban on Chinese Repealed,” The New World (Seattle, WA), Oct 21, 1943.

[42] The Cannery Workers and Farm Laborer Union Local 7 Records, Box 34.

[43] “Japanese-Americans Loyal to U.S,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA), December 25, 1941.

[44] “Fascism and Racism,” The New Dealer (Seattle, WA), Feb, 1942.

[45] “Army Evacuates 225 Japanese,” The New Dealer (Seattle, WA), April 1, 1942.

[46] “Our Enemy Aliens,” The New Dealer (Seattle, WA), February 17, 1942.

lynchingwwii111242-400.jpg)

Mrs. Francis Brooks became a relief-struggle celebrity after losing her job with the Negro Federal Theatre Project as a result of funding cutbacks. Arrested for her relief office "sit down strike," she received an outpouring of sympathy. A delegation of 26 women from the Washington Commonwealth Federation attended her court hearing. Sunday News February 14, 1937

Mrs. Francis Brooks became a relief-struggle celebrity after losing her job with the Negro Federal Theatre Project as a result of funding cutbacks. Arrested for her relief office "sit down strike," she received an outpouring of sympathy. A delegation of 26 women from the Washington Commonwealth Federation attended her court hearing. Sunday News February 14, 1937