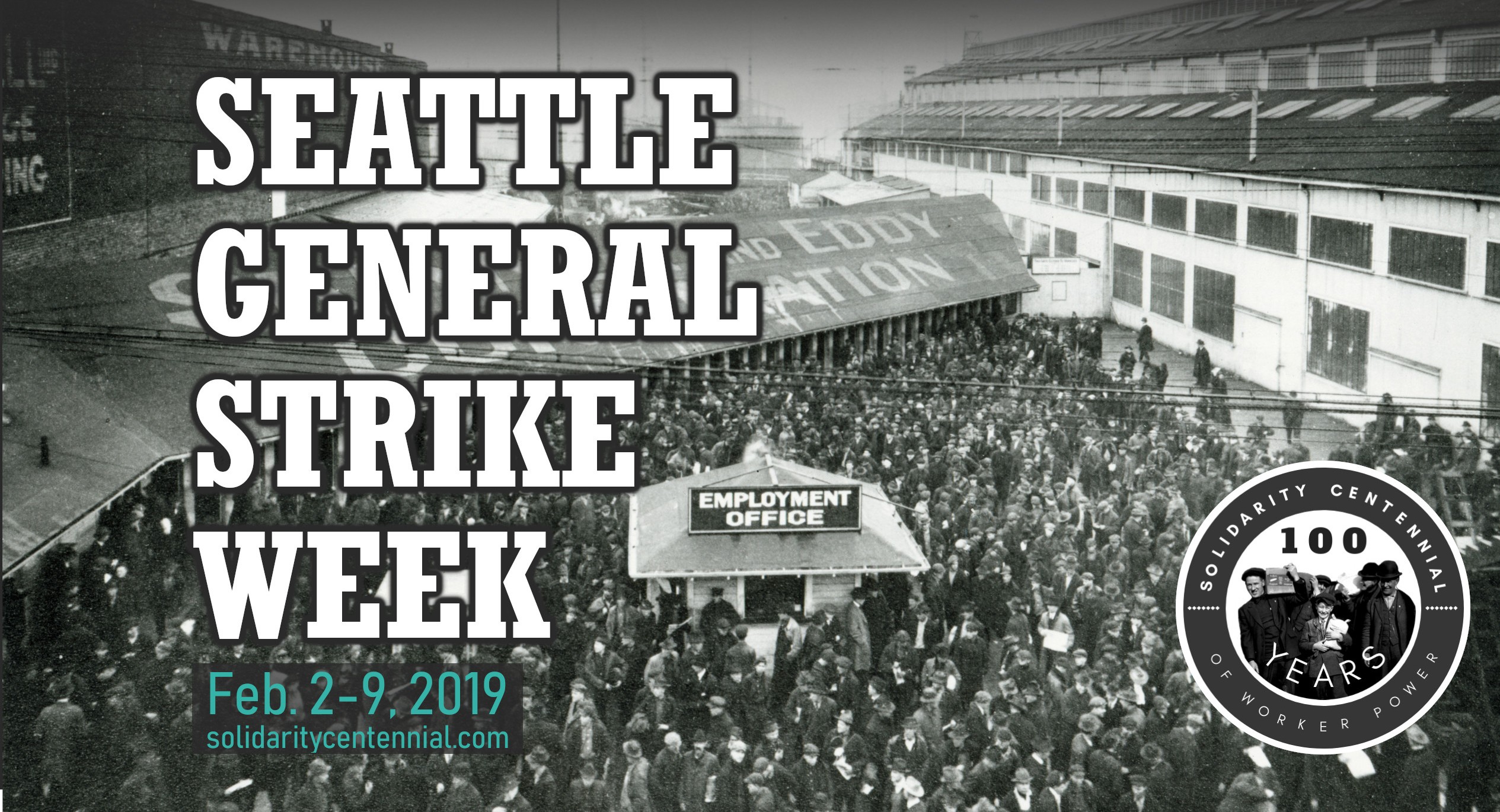

The Seattle General Strike of February 1919 was the first 20th-century solidarity strike in the United States to be proclaimed a “general strike.” It led off a tumultuous era of post-World War I labor conflict that saw massive strikes shut down the nation's steel, coal, and other industries and threaten civil unrest in a dozen cities. The Seattle General Strike Project is a multimedia website exploring this important event. It is part of the Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium based at the University of Washington.

On the morning of February 6, 1919, Seattle, a city of 315,000 people, stopped working. 25,000 other union members had joined 35,000 shipyard workers already on strike. The city's AFL unions, 101 of them, had voted to walk out in a gesture of support and solidarity. And most of the remaining work force stayed home as stores closed and streetcars stopped running. The city was stunned and quiet. While the mayor and business leaders huddled at City Hall, eight blocks away the four-story Labor Temple, headquarters for the Central Labor Council and 60,000 union members, hummed with activity. An elected Strike Committee had taken responsibility for coordinating essential services. Thousands were fed each day at impromptu dining stations staffed by members of the culinary unions. The teamsters union saw to it that supplies reached the hospitals, that milk and food deliveries continued. An unarmed force of labor's "War Veteran Guards" patrolled the streets, urging calm, urging strikers to stay at home. On the second day, the Mayor threatened to declare martial law and two battalions of US Army troops took up position in the city, but the unions ignored the threat and calm prevailed. "Nothing moved but the tide," remembered a striker years later.

In that sense, the strike was a success. Big strikes in the past had usually led to big violence, but this one remained completely peaceful, and in doing so provided a model for later mobilizations. On the other hand, it was becoming clear that the sympathy strike was not working. Most of the local and national press denounced the strike, while conservatives called for stern measures to suppress what looked to them to be a revolutionary plot. More important, the federal officials charged with managing the shipyards, refused to negotiate. Some of the unions wavered on the strike's third day. Most others had gone back to work by the time the Central Labor Council officially declared an end on February 11. By then police and vigilantes were hard at work rounding up Reds. The IWW hall and Socialist Party headquarters were raided and leaders arrested. Federal agents also closed the Union Record, the labor-owned daily newspaper, and arrested several of its staff. Meanwhile across the country headlines screamed the news that Seattle had been saved, that the revolution had been broken, that, as Mayor Hanson phrased it, “Americanism” had triumphed over “Bolshevism.” That was not story that most of the strikers would tell, nor the lesson that generations of labor activists would draw from it. The Seattle General Strike lasted only six days, but, in a variety of different ways, has continued to be of interest and importance ever since.

This multimedia website explores the history and consequences of the Seattle General Strike of 1919. Below you will find original research articles, digitized newspaper articles and other important documents, photographs, and extensive bibliographic materials. Start by watching two short videos, one produced by KCTS, the other an excerpt from Witness to Revolution: The Story of Anna Louis Strong produced and directed by Lucy Ostrander. Then read Roberta Gold's article from the Encyclopedia of Labor History Worldwide and "An Account of What Happened in Seattle and Especially in the Seattle Labor Movement, During the General Strike, February 6 To 11, 1919" written by Anna Louise Strong and members of the General Strike Committee. Daren Salter has created a dramatic slide show that tells the story of the strike with photos and headlines illustrating key events. The most detailed account is the new centennial edition of the The Seattle General Strike by Robert L. Friedheim brought up to date with an introduction, photo essay, and afterword by James N. Gregory.

The Labor Archives of Washingon recently published a spectacular online exhibit about the strike which features a detailed timeline and includes dozens of photos, pamphlets, minutes of strike committee meetings, IWW leaflets, and reports of agents hired to spy on labor activists. and documents. Visit the UW Libraries Special Collections, Labor Archives of Washington exhibit website.

Here is our interactive map showing the locations of important events and union headquarters in 1919. Use it to plan a walking tour of downtown Seattle.

We are pleased to also feature a unique and deeply researched report by historians Robert Cherny and Seth Bernstein about SEATTLE/SEIATEL' “The American Commune” in the Soviet Union, 1922-1939 that was founded by veterans of the general strike and other Pacific Northwest radicals, many of Finnish origin, who left the United States in order to follow their politics to the new Soviet Union.

The Politics of Gender in the Writings of Anna Louise Strong by Rebecca Jackson

In 1977, Professor Rob Rosenthal interviewed 35 men and women who participated in or remembered the 1919 General Strike. Rosenthal has generously agreed to share these oral histories with the Seattle General Strike Project. These audio MP3 files and transcripts comprise a rare and valuable resource. The narrators speak not only about the events of 1919 but about later aspects of Pacific Northwest labor and political history. Dave Beck is the most famous of the men and women interviewed. Later to serve as President of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Beck was 24 years old at the time of the General Strike, newly discharged from the Navy and was part of a group of Teamsters who opposed the strike.

This lesson plan by Omar Crowder is designed for an 11th grade class. Click here. It satisfies national and state standards and requires students to write an opinion-editorial (op-ed) piece and give a class presentation. It is made available by the Northwest History Consortium of the Northwest Educational Service District. NWEWSD's area includes 35 public school districts and several private schools in Island, San Juan, Skagit, Snohomish, and Whatcom counties.