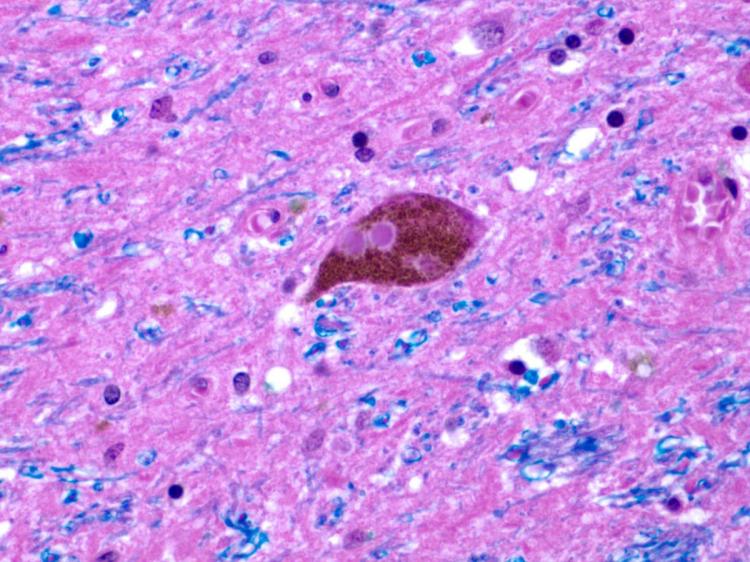

A stained slice of brain tissue with a Lewy body, a common form of pathology in Parkinson's disease. Courtesy Paul Crane

In the largest ever study on the topic, UW Medicine researchers have found no link between a serious head injury and later life Alzheimer-type dementia—but the research, published in the current issue of JAMA Neurology, did discover a three-fold elevated risk for Parkinson’s disease. Dr. Paul Crane gives us context for news that goes against conventional medical wisdom.

Dr. Paul Crane, Professor in the UW Department of Medicine, works in the field of Alzheimer's research. Since 2002, he has been involved with the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study, a 30-year collaboration of UW and Group Health Cooperative to advance understanding of factors associated with outcomes of dementia and cognitive decline.

To draw conclusions about life events and later dementia, you must need to study a lot of people. How did the design of this new study accomplish this feat?

We leveraged three valuable resources, the UW and Group Health Adult Changes in Thought Study (ACT) and the Rush University Religious Orders Study and Memory and Aging Project led by Dr. David Bennett. Starting in the 1990s, all three of these ongoing studies enrolled participants who were free of dementia, and followed them every one or two years until dementia and/or death and autopsy.

These long-running studies have substantial power to reveal how certain exposures influence risk for dementia and development of neuropathology findings in the brain at autopsy. Because the participants are not selected on the basis of vulnerability to disease or injury, findings from these cohorts are fairly generalizable to the general population.

For this investigation, each study asked participants at the time of enrollment and at each study visit about exposure to head injury. We focused on traumatic brain injuries (TBI) accompanied by a loss of consciousness, and we considered two severities: people with a loss of consciousness that lasted up to 60 minutes, and those with a loss of consciousness that lasted more than an hour. Each of the studies collected extensive clinical data during life. Across all three studies, we had access to neuropathology findings from almost 1,600 brains.

The neuropathology team led by Dr. Dirk Keene, Associate Professor in the UW Department of Pathology, performed careful and extensive neuropathological characterization of the brain tissue from the ACT study, quantifying the plaques and tangles of Alzheimer disease, Lewy bodies, which are commonly seen in Parkinson's disease, and other signs of pathology. At the same time, Dr. Julie Schneider, Professor of Pathology at Rush, performed careful and extensive neuropathological characterization of the brain tissue from the ROS and MAP studies.

We used these data to evaluate associations between head injury with loss of consciousness and risk of clinical and neuropathology outcomes.

It’s a common story that a traumatic brain injury can lead to later Alzheimer’s dementia in the general population. But in reality, the data has been inconclusive. What does this new research have to say about that?

We had a lot of power to find that story and we didn’t. We found no association at all between head injury during life with Alzheimer-type dementia or the plaques and tangles of Alzheimer disease in the brain. These conditions are very common by the end of life, so we had enough power to find associations between head injury and these Alzheimer’s disease outcomes, had they been there. It is a pretty strong negative study and contrary to what the field has found.

Interestingly, we did find an association between head injury with loss of consciousness for an hour or more and the risk for Parkinson’s disease. That association has been reported before, but not through a similar study design or with comparison to Alzheimer’s risk in the same population. We found that this type of serious head injury raises the risk for progression of parkinsonian symptoms, clinical Parkinson’s disease, and Lewy bodies in the brain at the time of death. Strikingly, we didn’t find this relationship with clinical Alzheimer’s disease, even though it is ten fold as common as Parkinson's Disease, or with plaques and tangles, which are more common than Lewy bodies.

We noticed that the people with a head injury lasting an hour or more were often younger than 25 years at time of injury. So we did a secondary analysis, and found the same thing. So, our study specifically earmarks a head injury before age 25 as being associated with Parkinson’s disease risk at least 40 years later, in a way it wasn’t before.

How big of a risk are we talking about? Is it something to worry about?

We were only able to detect the signal of Parkinson’s risk because the population was so large. The population-attributable risk—what proportion of Parkinson disease in the overall population is due to head injury—is going to prove to be fairly low because only twenty percent of our cohort had head injury exposure, and not all of them got Parkinson’s, of course. So, there’s an increased risk, but not to an infinite one.

I don’t know if this information changes what we need to do for people. It seems to me that if we can avoid head injuries, this study gives yet more rationale for doing so, especially considering our finding that children and teens with a head injury carry an increased risk of later life Parkinson’s. Will this information change the behavior of a 17 year-old? I doubt it. Will it change the behavior of adults responsible for allowing school districts to offer football? I hope so. This new information suggests that head injuries sustained early in life lead to increased risk for Parkinson’s disease late in life. Our findings are similar to others that suggest quite clearly that activities with high risk of head injuries should probably be avoided.

Does this study say anything about early-onset Alzheimer’s disease that occurs before age 65?

Our paper neither confirms nor denies any relationship with earlier onset neurodegenerative disease. The exposure we studied was the most common head injury exposure, which is a head injury followed by what appears to be a return to the prior level of cognitive function and the prior level of activity. There are some people with head injuries –especially severe head injuries – who never return to their prior level of functioning. These people with lingering effects of a head injury would be ineligible to join the ACT study. Since people needed to be free of dementia to join any of the studies included here, and enrollment age was at least age 65, by definition we could not say anything about early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Dr. Dirk Keene studies brain tissue under the microscope

Were there any memorable challenges in the course of this study?

One of the differences between the UW and the Chicago study designs became very relevant. The Chicago groups measure Parkinsonism in every participant with a special exam of arm and leg movement. They also ask people if they have ever had a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. We haven’t done that in Seattle with ACT, but because our participants come exclusively from Group Health, we have extensive medication and clinical records. So, we had to come up with a creative solution. I worked with Dr. James Leverenz of the Neurology Department of the Cleveland Clinic to go through all of the medications available at the Group Health formulary over the years, and we ended up identifying combinations of medications used to treat Parkinson disease along with relevant clinical relevance.

We also worked to address some differences in the neuropathology evaluation protocols between the Rush studies and the ACT study, which enabled us to leverage the extensive data from these three large studies together and, therefore, comment on the relevance of relatively uncommon exposures such as TBI. We are hopeful that many future studies will benefit from these initial efforts to harmonize the neuropathology data across these studies. —Genevieve Wanucha