Genevieve Wanucha

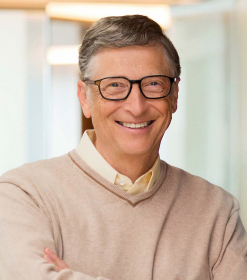

When Bill Gates visited for the 20th anniversary of the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, September 25–27, 2017, he spoke of his work to reduce the burden of childhood diseases in the developing world. In his keynote, he said that the GBD report, created by Dr. Christopher Murray and Dr. Alan Lopez of the UW Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), served as the impetus for the global health work of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation— now the world’s largest foundation, with $40 billion in assets. The Gates' work with UW researchers honed in on the most impactful ways to reduce human suffering around the globe. More than two decades later, the number of children under age 5 dying annually from diarrhea has dropped more than 75%.

I attended this conference to hear from this unique individual and his fascinating and impactful work—but, of course, I was listening for any mention Alzheimer's disease and related conditions. My ears perked up during the discussion after Bill Gate's keynote speech. Alzheimer's disease came up in the context of the dramatic shift in disease burden in rich and middle-income countries. For example, Gates referenced the huge challenge coming for the health systems of India and South Africa, which face both the remaining challenge of infectious disease and rising numbers of cases of diabetes, obesity, and Alzheimer's and related neurological conditions, diseases more common to rich countries.

I have been wondering ever since whether dementia - one of the fastest growing burdens on healthcare systems in developed countries-pushes this class of brain diseases into a target of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, even though the foundation focuses on communicable diseases.

Now we have the answer. Today, Bill Gates announced on his blog that he is "digging deep into Alzheimer's" by contributing (100 million dollars total) 50 million dollars of his own money into a private fund working to diversify the clinical pipeline and identify new targets for treatment. The Dementia Discovery fund, based in London, will not only pursue the amyloid and tau pathways of neurodegenerative diseases but also support startups exploring less mainstream approaches to treating dementia.

I believe that we can alter the course of Alzheimer’s. That’s why I’m investing in the Dementia Discovery Fund. https://t.co/7fcixpeJd5

— Bill Gates (@BillGates) November 13, 2017

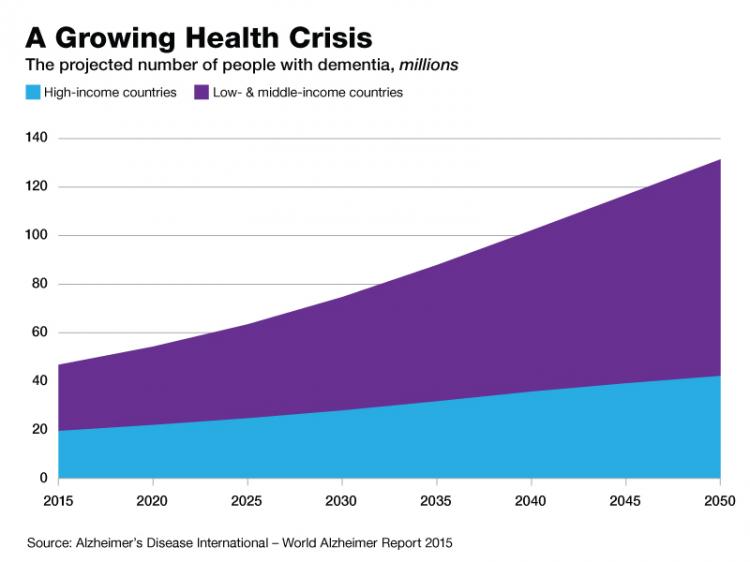

Indeed, his motivation comes from both the human (and personal) emotional toll of dementia and the more quantifiable financial and economic costs. "These costs represent one of the According to the Alzheimer’s Association, Americans will spend $259 billion caring for those with Alzheimer’s and other dementias in 2017," he writes. "Absent a major breakthrough, expenditures will continue to squeeze healthcare budgets in the years and decades to come. This is something that governments all over the world need to be thinking about, including in low- and middle-income countries where life expectancies are catching up to the global average and the number of people with dementia is on the rise."

*

As always, Bill Gates bases his action on a firm understanding of the science and lots of research. "What I’ve heard from researchers, academics, funders, and industry experts makes me hopeful that we can substantially alter the course of Alzheimer’s [in 10 years] if we make progress in five areas. These goals largely align with our vision at the UW Alzheimer's Disease Research Center/ UW Memory and Brain Wellness Center:

1. We need to better understand how Alzheimer’s unfolds- The brain is a complicated organ. Because it’s so difficult to study while patients are alive, we know very little about how it ages normally and how Alzheimer’s disrupts that process. Our understanding of what happens in the brain is based largely on autopsies, which show only the late stages of the disease and don’t explain many of its lingering mysteries. For example, we don’t fully understand why you are more likely to get Alzheimer’s if you’re African American or Latino than if you’re white. If we’re going to make progress, we need a better grasp on its underlying causes and biology.

2. We need to detect and diagnose Alzheimer’s earlier - Since the only way to diagnose Alzheimer’s definitively is through an autopsy after death, it’s difficult to identify the disease definitively early in its progression. Cognitive tests exist but often have a high variance. If you didn’t sleep well the night before, that might skew your results. A more reliable, affordable, and accessible diagnostic—such as a blood test—would make it easier to see how Alzheimer’s progresses and track how effective new drugs are.

3. We need more approaches to stopping the disease - There are many ways an Alzheimer’s drug might help prevent or slow down the disease. Most drug trials to date have targeted amyloid and tau, two proteins that cause plaques and tangles in the brain. I hope those approaches succeed, but we need to back scientists with different, less mainstream ideas in case they don’t. A more diverse drug pipeline increases our odds of discovering a breakthrough.

4. We need to make it easier to get people enrolled in clinical trials - The pace of innovation is partly determined by how quickly we can do clinical trials. Since we don’t yet have a good understanding of the disease or a reliable diagnostic, it’s difficult to find qualified people early enough in the disease’s progression willing to participate. It can sometimes take years to enroll enough patients. If we could develop a process to pre-qualify participants and create efficient registries, we could start new trials more quickly.

5. We need to use data better. Every time a pharmaceutical company or a research lab does a study, they gather lots of information. We should compile this data in a common form, so that we get a better sense of how the disease progresses, how that progression is determined by gender and age, and how genetics determines your likelihood of getting Alzheimer’s. This would make it easier for researchers to look for patterns and identify new pathways for treatment.

We'll be closely following along on this new effort to chase new theories and improve the efficiency of drug development and clinical trials. Any advances made in these 5 areas will benefit all of us.