With no digital records available, we read Deed Books in the state regional archives for Clallum, Grays Harbor, Island, Kitsap, and Mason counties. Our colleages at Eastern Washington University researched two southwestern counties and most eastern counties the same very slow way.

With no digital records available, we read Deed Books in the state regional archives for Clallum, Grays Harbor, Island, Kitsap, and Mason counties. Our colleages at Eastern Washington University researched two southwestern counties and most eastern counties the same very slow way.

All maps and data on these project pages should be considered preliminary. Additions and corrections are expected. This warning reflects the difficulties encountered as we searched through more than 7 million property documents in Washington counties. Here we explain the challenges and our methods.

Each county establishes its own rules for recording deeds and other property documents and its own ways of preserving records and making them available to the public. Some counties have managed to scan and digitize records, others have not. A few have microfilmed their records, but for a number of counties we were required to flip through tens of thousands of pages in bound volumes, trying to quickly spot sentences containing racial restrictions. We missed many. Also because of the enormous time and cost of this slow process, we reduced the search years when samples yielded few restrictions.

Clallum, Grays Harbor, Island, Kitsap, Mason, and Wahkiakum records were searched in this way, with results that should be regarded as incomplete. That caveat also applies to Skagit and Jefferson counties whose documents we read on microfilm, again by looking at thousands of images while trying to quickly notice a restriction buried in long paragraphs. Pacific County records were not accessible during our research schedule.

When digital copies were available there were also challenges. Our first step was to run the digital images through an Optical Character Recognition (OCR) program. We used Tesseract, an open-source program developed by Google. The quality of the digital images varies and some are too poor to be accurately rendered, making them inadequate for the next step which involved computer searches for suspect keywords. As a result, we missed many documents that included restrictions. In a comparison test involving a sample of records, we found that the slow in-person process of reading page by page in the bound volumes yielded more restrictions than the computerized search.

The records of King County were especially complicated. Years ago, King County Archives managed to scan its early records, but funds ran out as scanning reached 1930. All records from 1930 through 1972 remain on microfilm. We spent months reading microfilm but then were able to rent a high-speed microfilm scanner and with the Archives permission produced a digital version of most records from 1930-1953 (roughly 1.5 million scanned images). However, because the original microfilm quality was often poor, the subsequent OCR and search steps missed an unknown number of the documents that would have been identified with a more thorough search. Like the others, our King maps reflect an undercount.

Date range note: The OCR program we used cannot read hand-written text, so the date range of our research is limited. In most counties, typed records were introduced in the 1910s. Pierce was earlier (1907) and in that year we found the earliest restriction mentioned in this project. There may be earlier restrictions. We also may be missing restrictions recorded in the 1950s and after. As noted, we suspended research in counties lacking digital records when the yield thinned. For King county we also suspended research in the early 1950s and most others at the end of that decade. A more expansive search may turn up more restrictions.

Confirmation and data entry

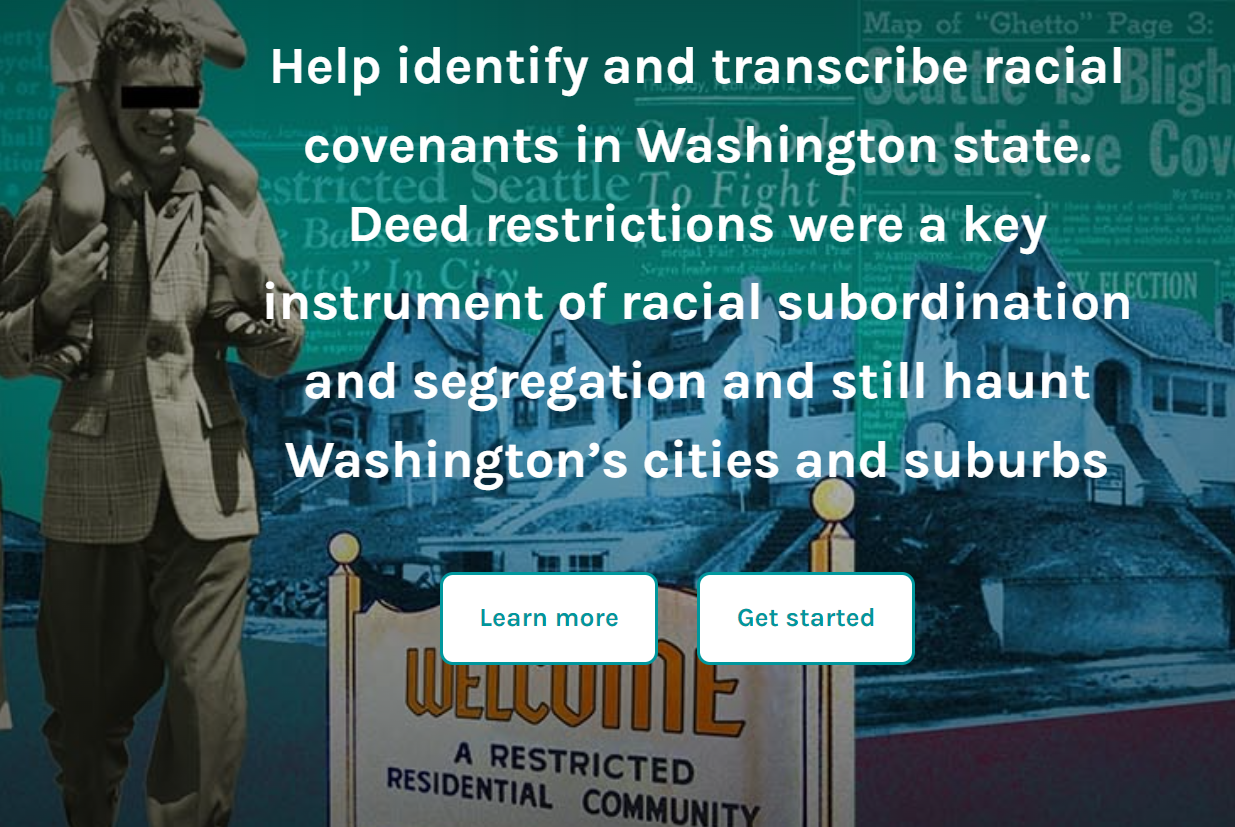

More than 1,900 volunteers helped us confirm restrictive documents and enter data using the Zooniverse crowd-research platform.

More than 1,900 volunteers helped us confirm restrictive documents and enter data using the Zooniverse crowd-research platform.

Computer searches miss restrictions and also eroneously flag documents. Confirmation is essential. Our research team handled some of this, but we also had help from more than 1,900 community volunteers who assisted by reading deeds and recording the information we needed to map the restricted parcels and subdivision. To coordinate this crowd-source work, we used the Zooniverse platform. Zooniverse is a citizen science web portal operated by the Citizen Science Alliance. It is home to some of the Internet's largest, most popular, and most successful citizen science projects. Millions of volunteers from around the world have helped with projects like ours.

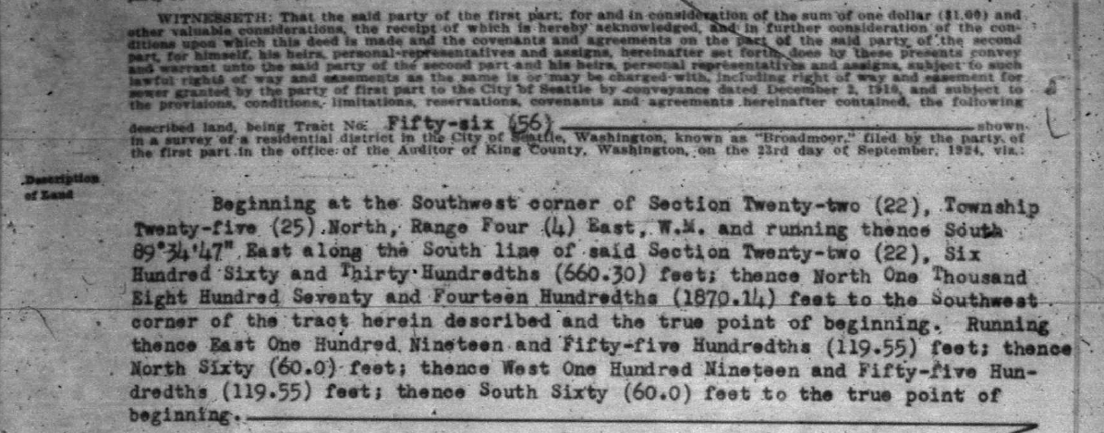

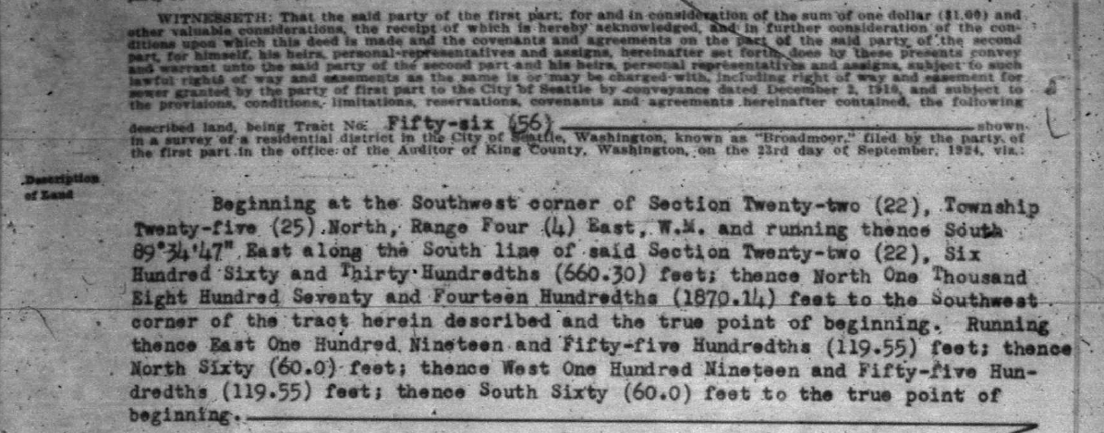

For confirmed documents we recorded the wording of the racial restriction, the name of sellers and buyers, date of sale or recording, and location information. Locations are complicated. Because addresses change, counties record locations using the name of plat that was registered when the subdivision was created, along with block and lot numbers within the plat. But some of documents were recorded in areas that had not been platted, so their locations are written as what surveyers call "Metes and Bounds" which are difficult to translate into contempory terms, as can be seen below. We have managed to translate and map only some of these restrictions.

Mapping methods and limitations

To produce maps we needed to match original property descriptions with current parcel data maintained by counties. This can be difficult because property lines may have changed over time and even when they did not, we often needed to go back and forth between old plat maps and current parcel maps to find individual lots. Errors were inevitable and our maps should be used with caution.

The steps so far described consumed thousands of work hours by a staff of talented University of Washington students. In the four years that the project was funded (July 2021-June 2025), the team searched roughly seven million documents, confirming almost 15,000 restrictive property documents covering almost 80,000 parcels. Unfortunately, we were not able to complete everything that we hoped. As the end of funding approached, it was necessary to triage our plans.

Many restrictive documents involved more than one parcel, often entire plats/subdivisions. We prioritized showing these areas in maps. The rest were deeds to individual properties and here we made a choice.

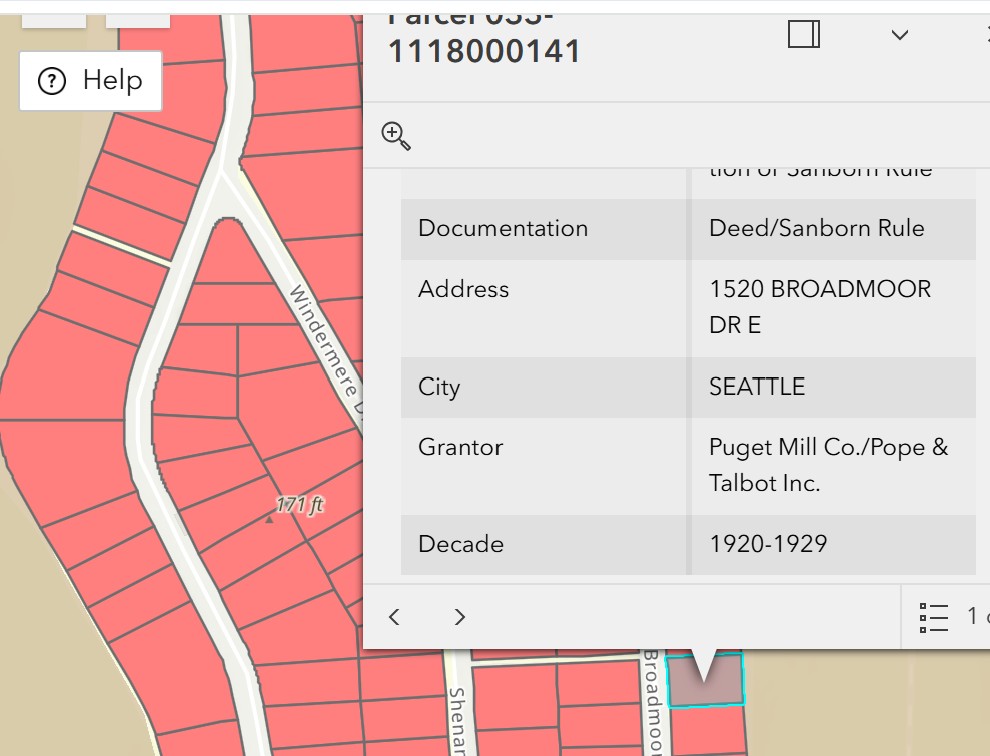

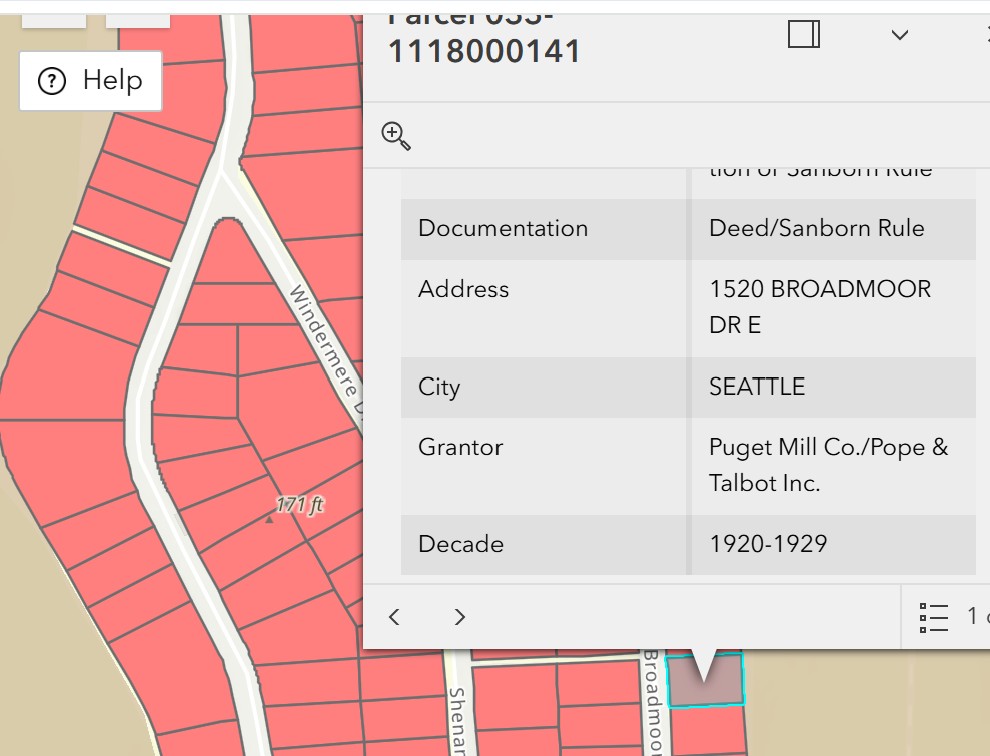

This detail from our King County map shows a Broadmoor parcel and our use of the Sanborn rule.

This detail from our King County map shows a Broadmoor parcel and our use of the Sanborn rule.

In a number of subdivisions, the developer sold hundreds of properties, each with identical restrictions embedded in deeds of sale. Our searches located most of these deeds but for reasons explained above some remain missing. Rather than trying to plot each one individually we marked all properties in these subdivisions as restricted. This saved time and also matches the legal principle that would have been invoked in court during the decades when covenants were legally enforcable.

On our maps these parcels are labeled as restricted by the "Deed/Sanborn rule." Courts usually ruled that restrictions were enforceable even if not mentioned in a deed of sale if the developer had routinely imposed them in earlier sales, holding that buyers should have known the rules. This derived from a 1925 Michigan Supreme Court decision in Sanborn v. McLean. Above is an example of how we use the Sanborn shortcut in the Broadmoor neighborhood of Seattle where we found 281 restrictive documents, all imposed by Pope & Talbot timber company when they developed the area in the 1920s. Today Broadmoor includes 320 parcels according to county maps. We label all of them restricted according to the Sanborn rule.

Acknowledgements

Our colleagues at Eastern and Washington University carefully read the deed volumes for Clark and Wahkiakum counties, both in our western Washington zone. In turn we handled all of the computational work for eastern counties, running OCR programs, computer searches, and Zooniverse set-up for Chelan, Columbia, Douglas, Franklin, Garfield, Okanagon, Spokane, Stevens, Whitman, and Yakima counties

An extraordinary staff of University of Washington students and recent students made all of this possible. The initial team in summer 2021 consisted of Sophia Dowling and Jazzlynn Woods handling research with Nicholas Boren designing software and computations, and Madison Heslop serving as project coordinator. In 2022, Alvin Bui, Samantha Cuts, Erin Miller, and Liz Peng joined as Madison and Jazzlynn left UW, Liz designing maps while Alvin served as coordinator. With renewed funding in 2023, we reorganized and expanded. Sophia Dowling became project manager while Sophie Belz, Ella Gouran, Isabel Smith, and David Cunningham replaced Erin and Samantha who were graduating. Nicholas, who had served as software engineer since the start, graduated in 2024 and first Runsen Wu, then Nandini Baliyan took over that critical work. Amanda Miller became project manager when Sophia left, and was joined by Ari Conboy, Emma Montovani, Bryce Penick, and Annika Tuohey for the final year of project as funded under HB1335. Please see their staff profiles.

And one more thank you. Dr. Eric Johnson is Director of Technical Services and Affiliate Assistant Professor in the Department of History. His advice and help have been indispensible.

With no digital records available, we read Deed Books in the state regional archives for Clallum, Grays Harbor, Island, Kitsap, and Mason counties. Our colleages at Eastern Washington University researched two southwestern counties and most eastern counties the same very slow way.

With no digital records available, we read Deed Books in the state regional archives for Clallum, Grays Harbor, Island, Kitsap, and Mason counties. Our colleages at Eastern Washington University researched two southwestern counties and most eastern counties the same very slow way. More than 1,900 volunteers helped us confirm restrictive documents and enter data using the Zooniverse crowd-research platform.

More than 1,900 volunteers helped us confirm restrictive documents and enter data using the Zooniverse crowd-research platform.