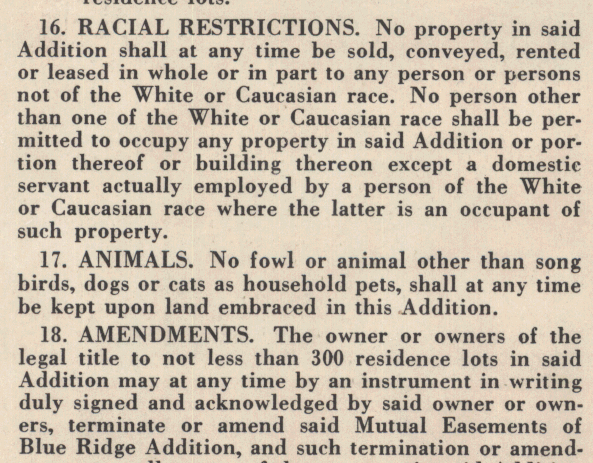

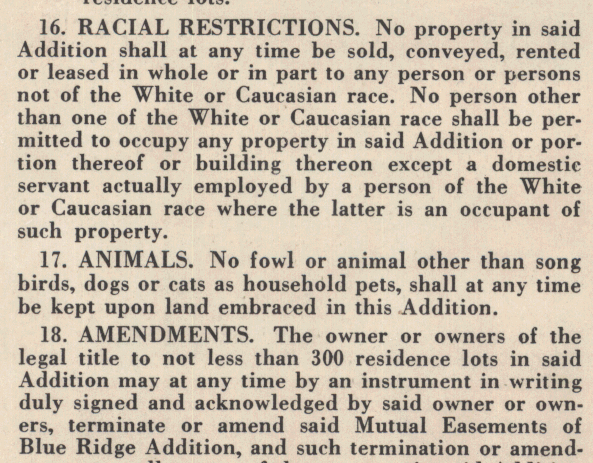

Excerpt from the list of restrictions in the homeowner's association bylaws for Blue Ridge, one of several neighborhoods in northwest Seattle and Shoreline developed and restricted by airplane industrialist William Boeing

by James Gregory

Excerpt from the list of restrictions in the homeowner's association bylaws for Blue Ridge, one of several neighborhoods in northwest Seattle and Shoreline developed and restricted by airplane industrialist William Boeing

by James Gregory

Racial restrictive covenants became a tool to restrict access and enforce segregation in cities and towns in Washington and across the United States in the early and middle 20th century. White supremacists had used other weapons in the late 19th century, including banning certain racial populations altogether. Early in its history, Seattle had an ordinance making it illegal for Indigenous Americans to reside within city limits. In the vicious mob campaigns of the late 1880s, Chinese people were driven out of towns and cities, including Seattle and Tacoma, and twenty years later the same brutal tactics were used in Bellingham to exclude South Asians. Nor would violence cease in the 20th century. Racial restrictive covenants were just one weapon in the arsenal of white supremacy.

In other states, segregationists initially used zoning laws to restrict access to property and housing (we have not yet found Washington examples). Restrictive covenants became the alternative promoted by real estate professionals after the Supreme Court ruled (1917) that segregation by zoning ordinance violated the 14th amendment.

Deed restrictions had many advantages. They could be enacted easily by registering a restriction with county authorities and at that point carried the force of law, enforceable as contracts in state courts. And they were supposed to be binding on future owners in perpetuity. Neighbors could challenges a sale or rental that violated the racial rules and get it reversed, at which point the new owner/renter would be evicted and the seller could be held liable for substantial damages.

This image from the brochure advertising properties for sale in the Shoreline community of Innis Arden assured would-be buyers that it was a "restricted community."

This image from the brochure advertising properties for sale in the Shoreline community of Innis Arden assured would-be buyers that it was a "restricted community."

Researchers in other states have found a few racial covenants dating from the 1890s. The earliest we have found so far in Washington is from 1907. They became much more common after 1926 when the Supreme Court ruled them to be enforceable contracts in the Corrigan v. Buckley decision. And even more popular during and after World War II as African Americans moved west in substantial numbers. Courts were supposed to stop enforcing them after the 1948 Shelley v. Kramer decision, but they remained perfectly legal until 1968 and we have found some counties recording new restrictive covenants as late as 1967.

The use of racial restrictive covenants was promoted in the first instance by real estate professionals, led by the American Board of Realtors (ABR). The ABR and its local affiliates conducted education campaigns starting in the 1920s and continuing into the 1950s to persuade land developers, neighborhood associations, and individual property owners to "protect" property with racial restrictive covenants.

In the mid 1930s, the Federal government joined the campaign. The Home Owners Loan Corporation drew "redlining maps" for major cities (including Seattle, Tacoma, Spokane) in 1936. These were intended to help banks and mortgage lenders determine safe and unsafe areas for investment. The color red marked neighborhoods deemed "hazardous" for lenders. Race was a primary condition of redlined neighborhoods and the HOLC awarded high scores to neighborhoods with restrictive covenants. So did the Federal Housing Association (FHA) which began underwriting home loans in the mid-1930s. FHA guidelines expressly advocated restrictive covenants. Another level of responsibility accrues to the state and local governments that allowed the restrictions to be recorded and gain legal status. Snohomish County recorded new restrictions as late as 1967.

Covenant types

Example of a restriction embedded in the plat itself. Click for readable copy.

Example of a restriction embedded in the plat itself. Click for readable copy.

The term racial restrictive covenant is used to describe several types of documents that property owners recorded with county auditor offices. They include:

The type of document has something to do with the age of neighborhoods. New subdivisions were easier to restrict than neighborhoods that had been established earlier. The developer of a new subdivision could easily add a restriction to the plat (a map showing streets and property lines) and register it with county authorities. The restriction would then apply to all properties and all future owners in perpetuity.

Often a racial restriction was one of a list of restrictions that might include prohibitions on pigs, cows, and horses, noxious enterprises, and various other matters, and might also dictate limits on set backs and building quality. Instead of a long list on the plat, the developer filed a separate document that county auditors call CC&Rs (conditions, covenants, and restrictions). Linked to the plat by a file number, CC&Rs have the same effect as a restriction in the plat itself, controlling what future owners can do with their property.

Some subdivisions are governed by Home Owners Associations (HOAs) to which every property owner belongs, and which is legally empowered to set rules and restrictions for the entire area. Condominiums are also governed by HOAs. HOA bylaws usually can be changed by a super majority of the community's owners. The neighborhoods of Broadmoor, Windermere, Blue Ridge, and Innis Arden are examples of HOA communities in the Seattle region that had long lasting racial restrictions in their bylaws.

It was more complicated to impose restrictions on older neighborhoods. Neighborhood associations might organize petition campaigns to convince fellow residents to bind their property with a racial covenant. One of the best documented efforts restricted most blocks in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle. Starting in 1927, the Capitol Hill Community Club organized a three-year campaign during which 964 property owners signed a petition covenant restricting 183 blocks with the following covenant:

“The parties hereto signing and executing this instrument and the several like instruments relating to their several properties in said district, hereby mutually covenant, promise and agree each with the other, and for their respective heirs and assigns, that no part of the lands owned by them as described following their signatures to this instrument, shall ever be used or occupied by or sold, conveyed, leased, rented or given to Negroes, or any person or persons of the Negro blood.”

This petition was set to expire after 21 years, which made it different than the restrictions that were supposed to stay with the property in perpetuity.

The fifth type of covenant involved individual deeds of sale. To make sure that each property owner fully understood the restrictions, many developers would include them in the deed of sale either in addition to a CC&R or in place of it. Here is an example.

Terms and Targets

Examples of restrictive covenants.

Examples of restrictive covenants.

The language used in restrictions varied widely, as did the targeted populations. Most restrictions in Washington state used a "white/Caucasian only" formula as in this one covering subdivisions developed by William Boeing, founder of Boeing Aircraft: “No property in said addition shall at any time be sold, conveyed, rented, or leased in whole or in part to any person or persons not of the White or Caucasian race.”

But some developers wanted more specificity, perhaps worried that the definition of "White or Caucasian race” was not clear. Instead of stating who would be included, they specified who would be banned.

The lists could be elaborate and shocking. The Pope and Talbot timber company subdivided vast acreages in King and Snohomish counties and usually applied the following:

"neither the said premises, or any house, building or improvement hereon erected, shall at any time be occupied by persons of the Ethiopian race, or by Japanese or Chinese, or any other Malay or Asiatic race, or any person of extraction or descent of any such race, save and except as domestic servants in the employ of persons not coming within these restrictions."

[Note: In the terminology of the 1920s-1940s "Ethiopians" meant all African ancestries; "Malays" meant Filipinos; "Mongolians" meant all East Asian ancestries; "Hindus" meant all South Asians. The exemption for domestic servants was very common in all of the counties we have researched.]

In one way or another, every restrictive document we have found in western Washington counties banned African Americans, and almost as frequently people of Asian ancestries. Although the "White/Caucasian only" language would have excluded Indigenous Americans, only in Olympia and Thurston County were Native peoples specifically mentioned.

A 1925 subdivision in Olympia, the state capital, employed this disturbing language:

"said premises shall never be sold, leased, or rented to any Negro, Mulatto, Indian, Chinaman, Japanese, or person of the so-called Yellow races.” Other Olympia developers, perhaps urged by the Board of Realtors, later adopted this phrasing, making it fairly common in Thurston County, used even in some of the subdivisions created by Olympia Federal Savings and Loan.

The range of targets and language is widest in King County where we also found some restrictions banning people outside the conventional racialized categories. Hawaiians were named in a few subdivisions, Italians added to the list of banned groups in a 1911 covenant, and "aliens" named in two more. And in the upscale Seattle neighborhood of Blue Ridge, the homeowners association banned descendants of anyone born in the "Turkish empire."

Jews were named in documents covering 18 out of the 620 subdivisions known to have been partly or fully restricted in King county, involving 2,000-2,500 properties. We were surprised that these numbers were not larger, and surprised again when we failed to find similar restrictions in other counties. This, of course, was not the only mechanism of discrimination that Jewish Americans faced.

It appears that antisemites used deed restrictions mostly in a particular category of neighborhood: high-end, and often gated, communities. Broadmoor, a gated neighorhood with a golf course, and the Sand Point Country club are Seattle examples. The Sand Point restriction read: "No tract shall be sold, conveyed, rented or leased, in whole or in part, to any Hebrew or to any person of the Malay, Ethiopian or any other negro or any Asiatic race; or any descendant of any thereof, except only employees in the domestic service on the premises of persons qualifies as herein provided as occupants."

Antisemitic restrictions sometimes refered to "Hebrews" or "Semites," but also could say that only those of the "white Gentile race" were allowed. One small subdivision near Bellevue allowed only "persons of the Aryan race."

Enforcement/Resistance

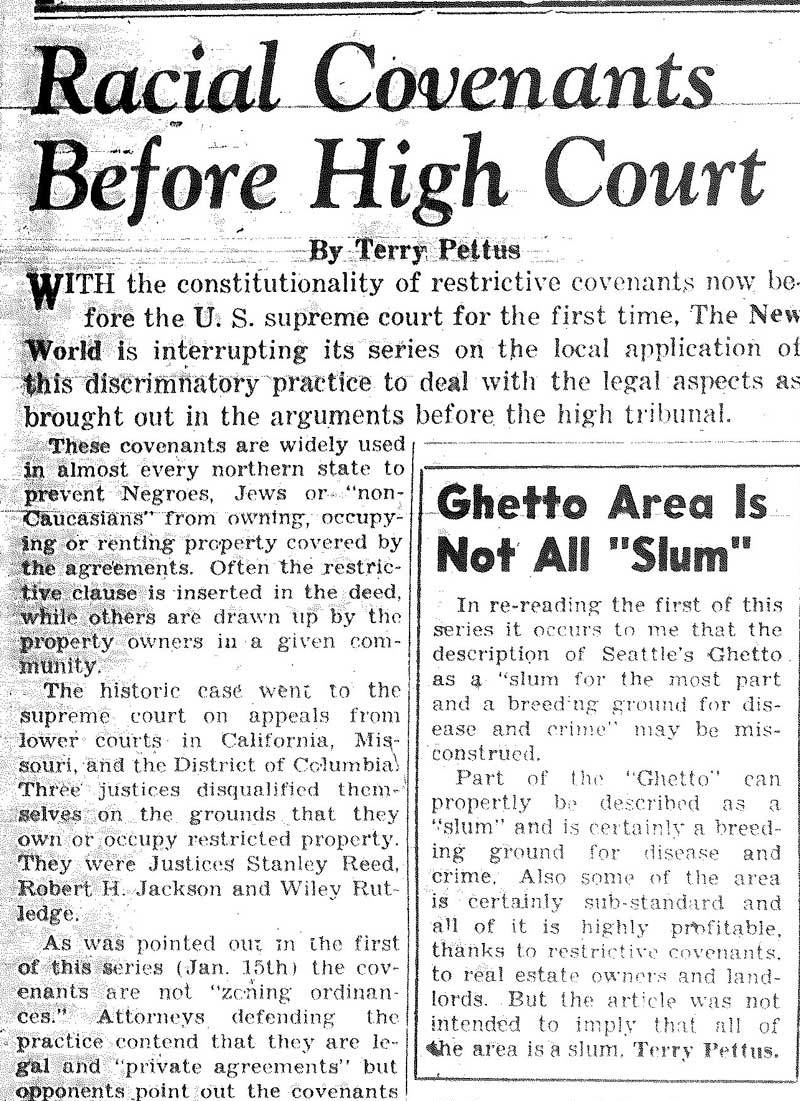

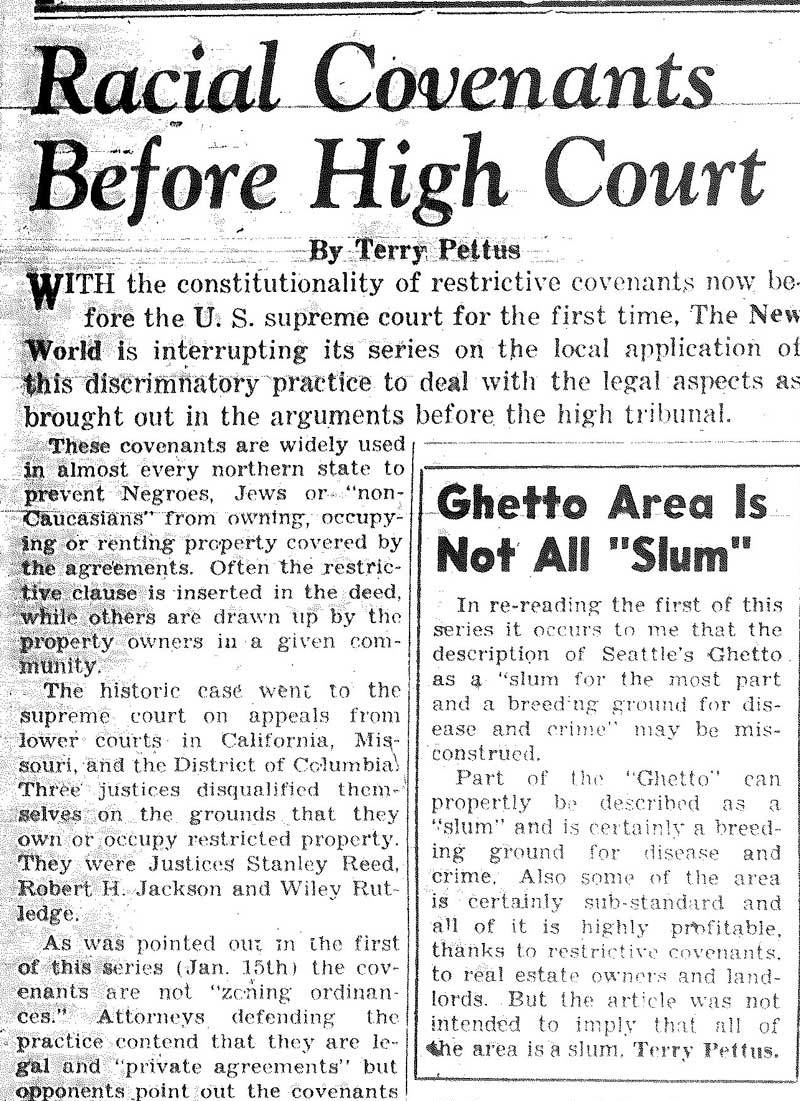

Click for larger version of article from the March 6, 1941 issue of the Washington New Dealer, a weekly associated with the Washington Commonwealth Federation and the Communist Party.

Click for larger version of article from the March 6, 1941 issue of the Washington New Dealer, a weekly associated with the Washington Commonwealth Federation and the Communist Party.

The NAACP, which had won the 1917 Buchanan v. Warley decision confirming the unconstitutional status of zoning ordinances that mandated racial segregation, worked for three decades to convince the Supreme Court to reach the same conclusion about racial deed restrictions. The Court rejected NAACP arguments about the 14th Amendment in the 1926 Corrigan v. Buckley case based on a Washington DC restrictive covenant and refused to revisit the ruling until the 1940s. But court decisions were of limited importance. Rarely did segregationists need to file lawsuits to block families of color from moving into a restricted neighborhood. That was handled by realtors who refused to show properties and warned off potential renters or buyers. And it was backed up by the threat of ostracism, harrassment, and violence that would likely greet a newcomer of the wrong background.

What happened to the Brooks family in 1941 illustrates the point that there were multiple means of enforcement. A civil rights activist, Carl Brooks and his family purchased a house in the restricted neighborhood of Lago Vista in Shoreline, north of Seattle's city limits. Instead of going to court, the Lago Vista Community Club organized a campaign of harrassment to force the Black family to leave. According to one source, the County sheriff supported the campaign -- an indication that his office treated Shoreline and other northern suburbs as "sundown zones" -- until the violence escalated. The Washington New Dealer reported the rest: "The campaign of intimidation and violence to force the Negro family to leave the modest home they purchased last October was climaxed on the night of Wednesday, February 26, when dynamite was thrown at the house in which two children were sleeping."

Still, it was not uncommon for the walls of restriction to crumble in areas near existing Black or Asian neighborhoods, especially in 1940s as the second Great Migration brought more and more African Americans to cities of the North and West. A two-block area in the Central District of Seattle had been restricted by a neighborhood petition in 1928, but by the 1940s the deed provisions were ignored as Black and Filipino families moved into the area.

This 1948 story in the New World, a weekly associated with the Washington Commonwealth Federation and the Communist Party, helped push the campaign to resist racial restrictive covenants.

This 1948 story in the New World, a weekly associated with the Washington Commonwealth Federation and the Communist Party, helped push the campaign to resist racial restrictive covenants.

Organized opposition to racist covenants increased in the 1940s with the Communist Party, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and several moderate civil rights groups joining the NAACP in calling attention to these instruments of segregation and exclusion. In Seattle, the Christian Friends of Racial Equality, a female-led coalition of Black, White, and (interestingly) Jewish women and men launched an information campaign in 1946 to discourage the recording of new restrictive covenants. The campaign enjoyed some success. The real estate industry paid little attention and developers continued to plat new subdivisions with restrictions, but some neighborhood petition campaigns failed when a small but significant number of white homeowners refused to sign. The most important example involved Capitol Hill, a Seattle neighborhood whose 183 blocks had been locked down by petition covenants that expired in 1948. The Capitol Hill Community Club's campaign to renew the restrictions generated less support than expected and while some restrictions were renewed, others were not.

As the Supreme Court heard arguments in the Shelley case, the New World began to profile the problem in Seattle

As the Supreme Court heard arguments in the Shelley case, the New World began to profile the problem in Seattle

The NAACP won its battle against restrictive covenants in the summer of 1948, when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of a St. Louis couple, J.D. and Ethel Shelley, who had purchased a house that was under a restriction. The Court ruled that the covenant was a private contract that had no standing in a court of law because enforcement by the state of Missouri or any other state would violate the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. Journalists often mistakenly assert that the Shelley v. Kramer decision made racial covenants illegal. Not at all. They remained legal and effective for another twenty years until Congress passed the Fair Housing Act in 1968.

The Shelley decision did not stop developers from writing restrictions into new deeds in the 1950s and 1960s and most counties continued to record them. Equally important, whites-only neighborhoods continued to enforce their covenants by other means. Catherine Silva has detailed an example. In 1952 (four years after Shelley) the Ornstein family purchased a home in a Seattle neighborhood which had been covenanted against Jews as well as people of color. The leader of the community club sprang into action, citing the restrictive covenant and vowing “the community will not have Jews as residents.” Civil rights groups, including the Jewish Anti-Defamation League and a nearby Methodist Church, tried to help, but in the end the threats worked. The Sand Point Community Club defended its racial covenant and the Ornstein family moved away. Six years later, in 1958, a mixed-race couple who had bought property in the University District of Seattle, gave up and moved away after a cross was burned in their front yard near the bedroom where their children slept.

Legacies

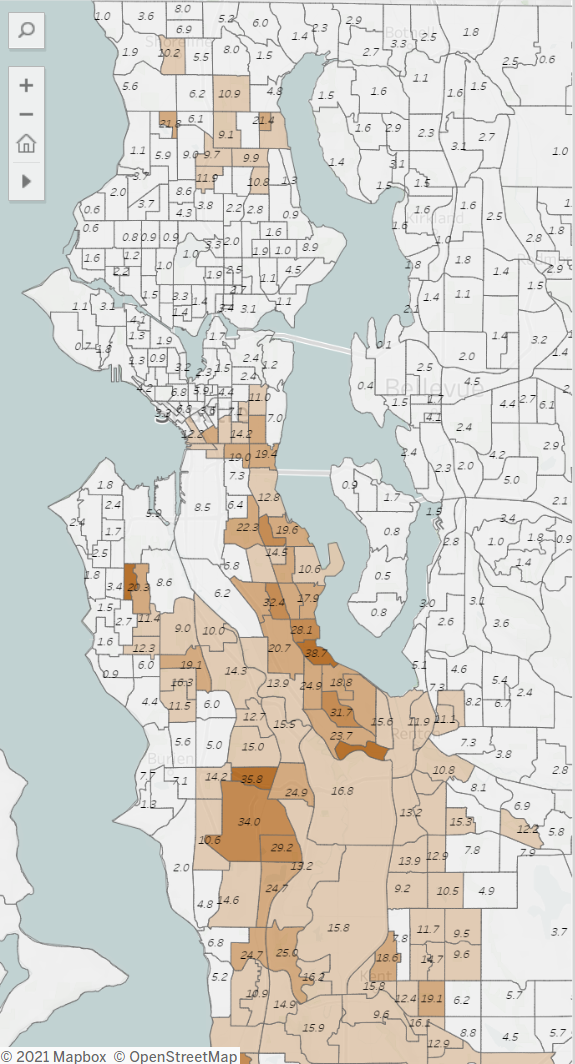

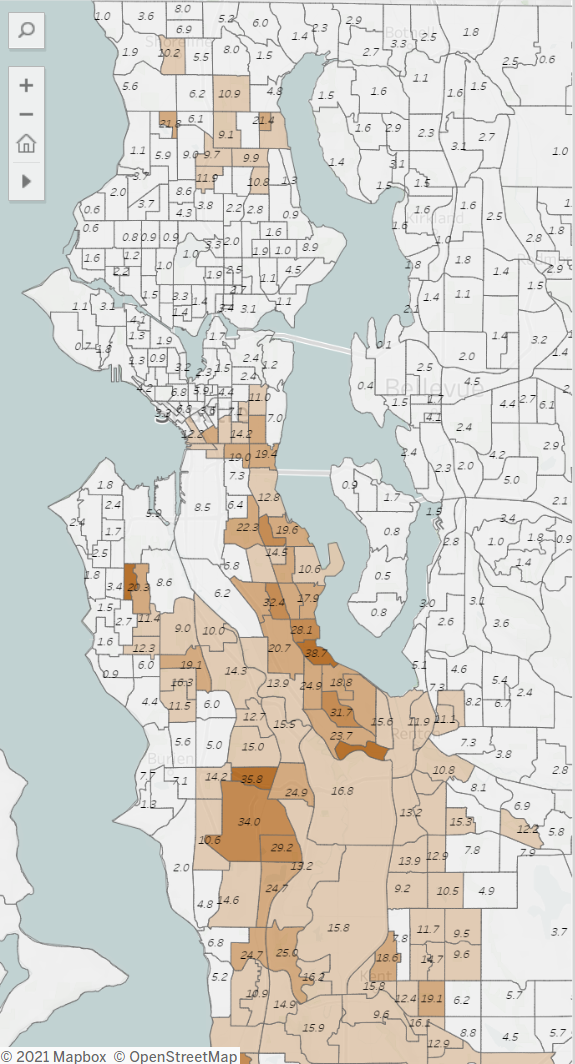

2020 distribution of African Americans in King County. This is one of the dozens of maps showing race and segregation for Black, Asians, Hispanics, Indigenous, and White persons in Washington counties 1940-2020.

2020 distribution of African Americans in King County. This is one of the dozens of maps showing race and segregation for Black, Asians, Hispanics, Indigenous, and White persons in Washington counties 1940-2020.

Since 1968, housing discrimination has been illegal. It has also been much too common. The Fair Housing Act and other civil rights laws against discrimination on the basis of race, sex, age, and disability are notoriously hard to enforce. In Washington cities and suburbs, it was decades before patterns of racial segregation began ease and the most recent (2020) census shows that not even the passage of half a century has erased the effects of racial restrictive covenants and other instruments of exclusion and segregation.

Racial restrictive covenants maintained much of their threat even after they became void. Many neighborhoods that had been restricted as a matter of law have kept that reputation decades and generations later. Biased "steering" by realtors, discriminatory behavior by parties selling or renting properties, stares and snubs by neighbors have continued to block open access through the years.

Another legacy is perhaps more important. Today's extreme disparities in homeownership and family wealth have everything to do with restrictive covenants and other instruments of exclusion that suppressed property ownership for persons of color through much of the 20th century. It was not just that families could not live in certain areas. Restrictions narrowed buying opportunites of any kind. And redlining doubled the damage, limiting access to loans and mortgages. In the era (1940-1970) when homeownership became standard for White families, including those of modest income, familes of color were shut out. And when restrictions finally began to ease, it was too late. Price appreciation since the 1970s has meant that one needs either a high income or property to exchange, or inter-generational wealth in order to purchase a home.

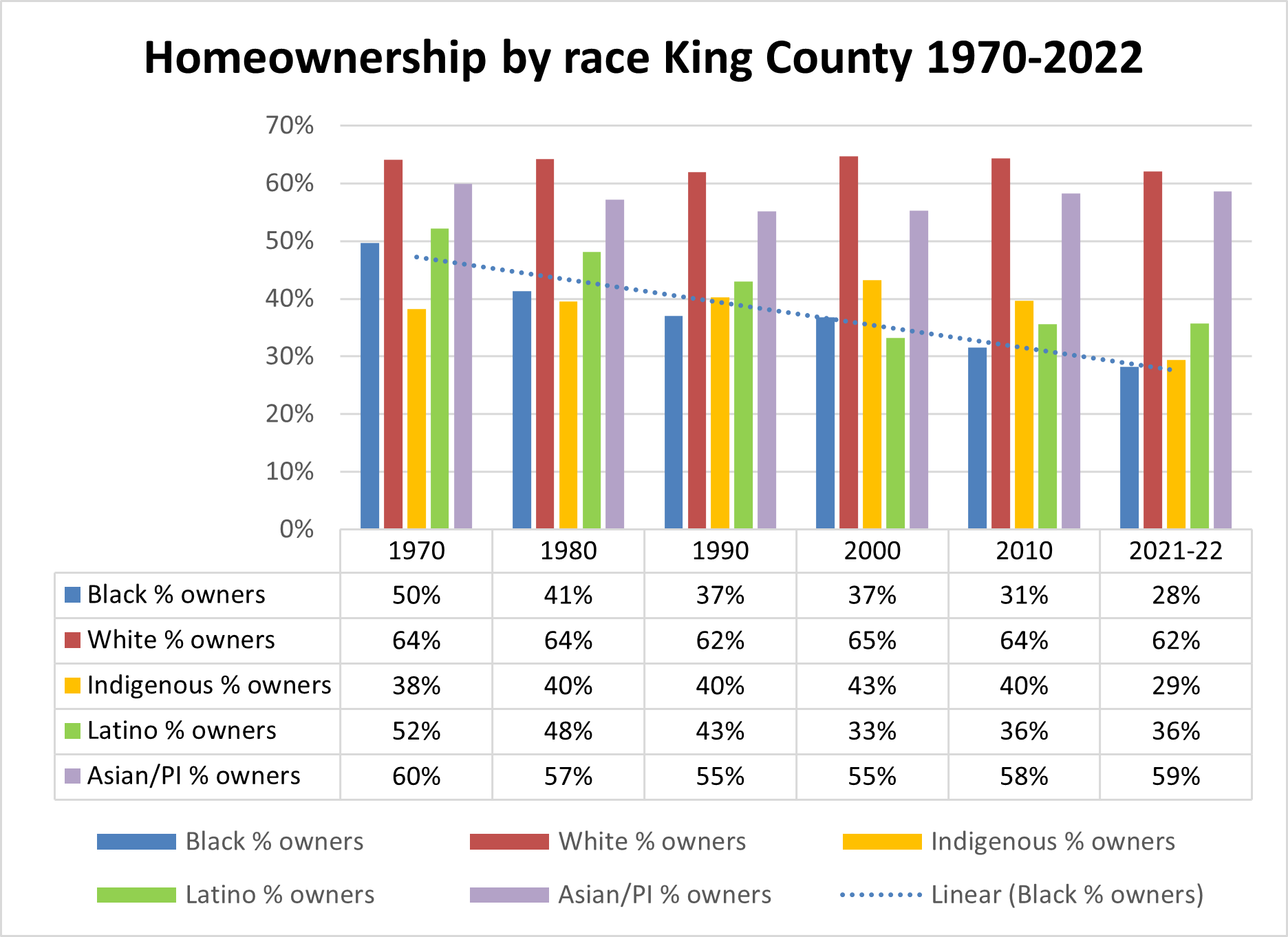

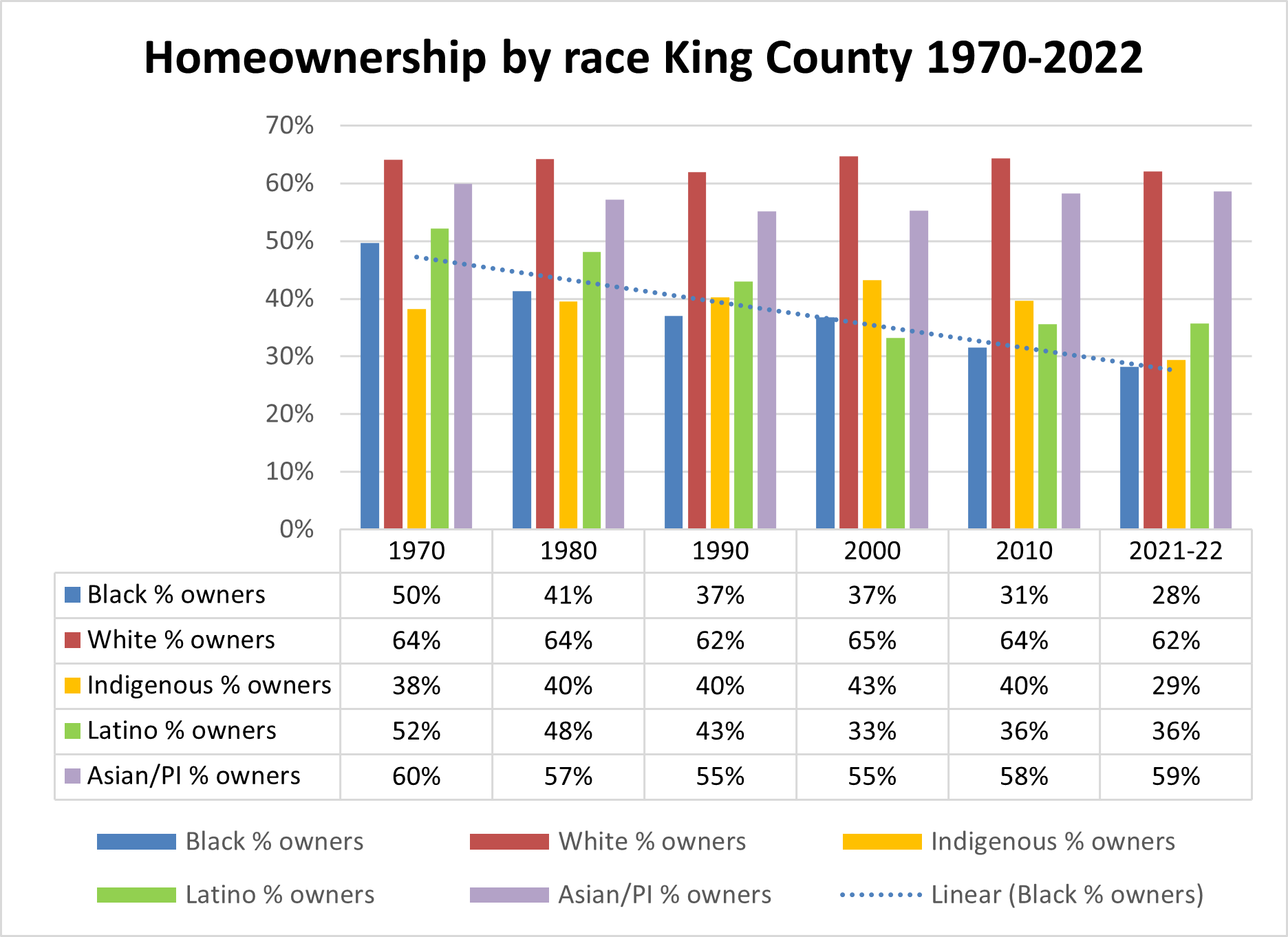

Homeownership rates by race Seattle/King County 1970-2022. Click to see more King County data. .

Homeownership rates by race Seattle/King County 1970-2022. Click to see more King County data. .

The chart at right shows the disparate homeownership rates for Seattle/King County. Notice that while most White families have owned homes, most Black, Latino, and Indigenous families do not. In the most recent census data the disparity is beyond alarming: 62% of White families are homeowners compared to only 28% of Black families. Fifty years ago, in 1970, 50% of Black families owned homes. Since them it has fallen decade after decade, accelerating since 2000, falling from 37% to only 28% in the last 20 years. The story is similar in other counties (here are charts for Pierce and Snohomish counties).

The disparate rate of homeownership is only part of the problem. The homes owned by Black, Indigenous, and Latino families tend to be worth less than those owned by Whites. In 2020, the small number of Black families in King County able to purchase a home (28%) owned property whose median value was just 75% of the median value of White-owned homes. This value disparity is not new. Since 1970 Black-owned homes have always been worth much less than homes owned by Whites.

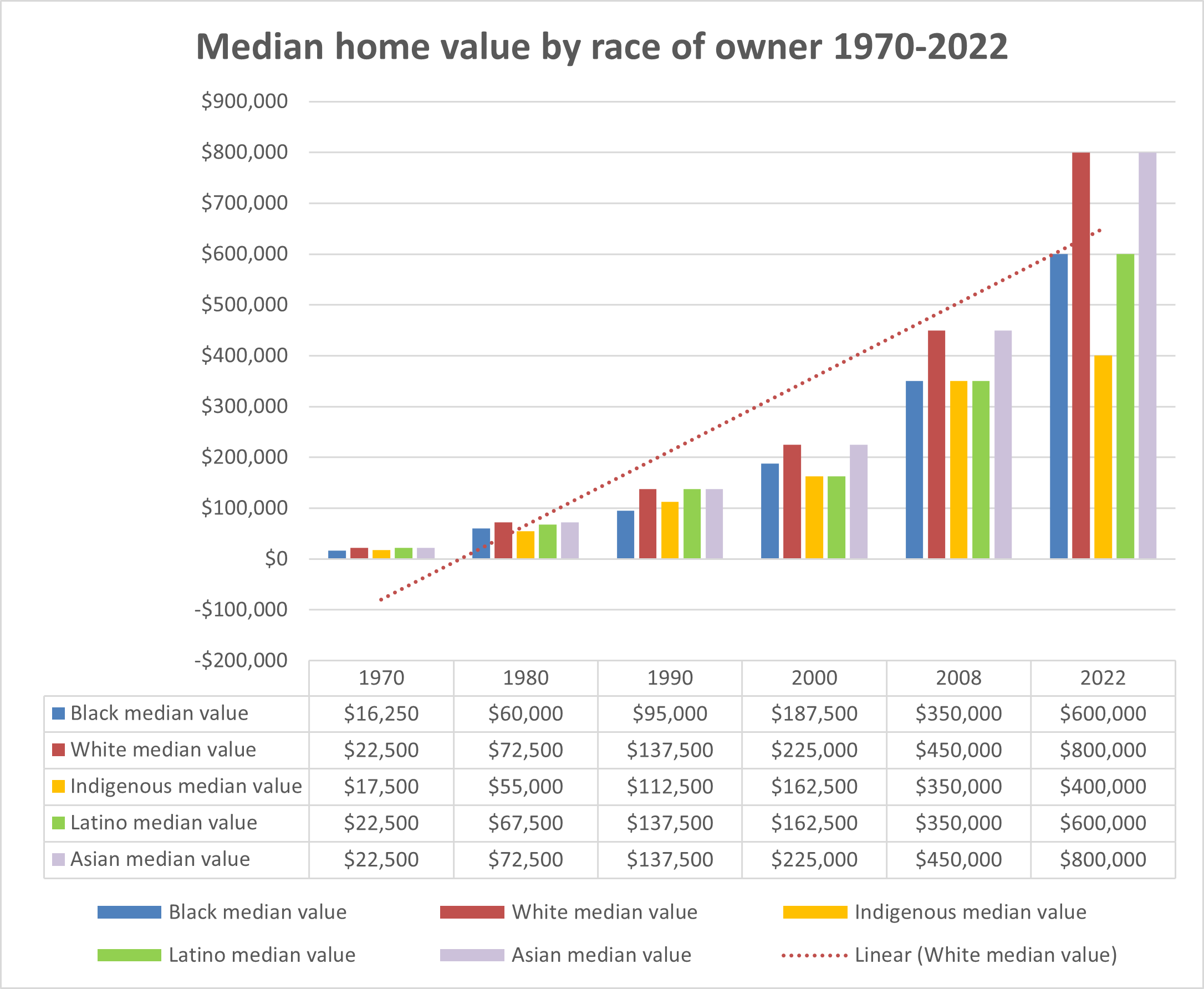

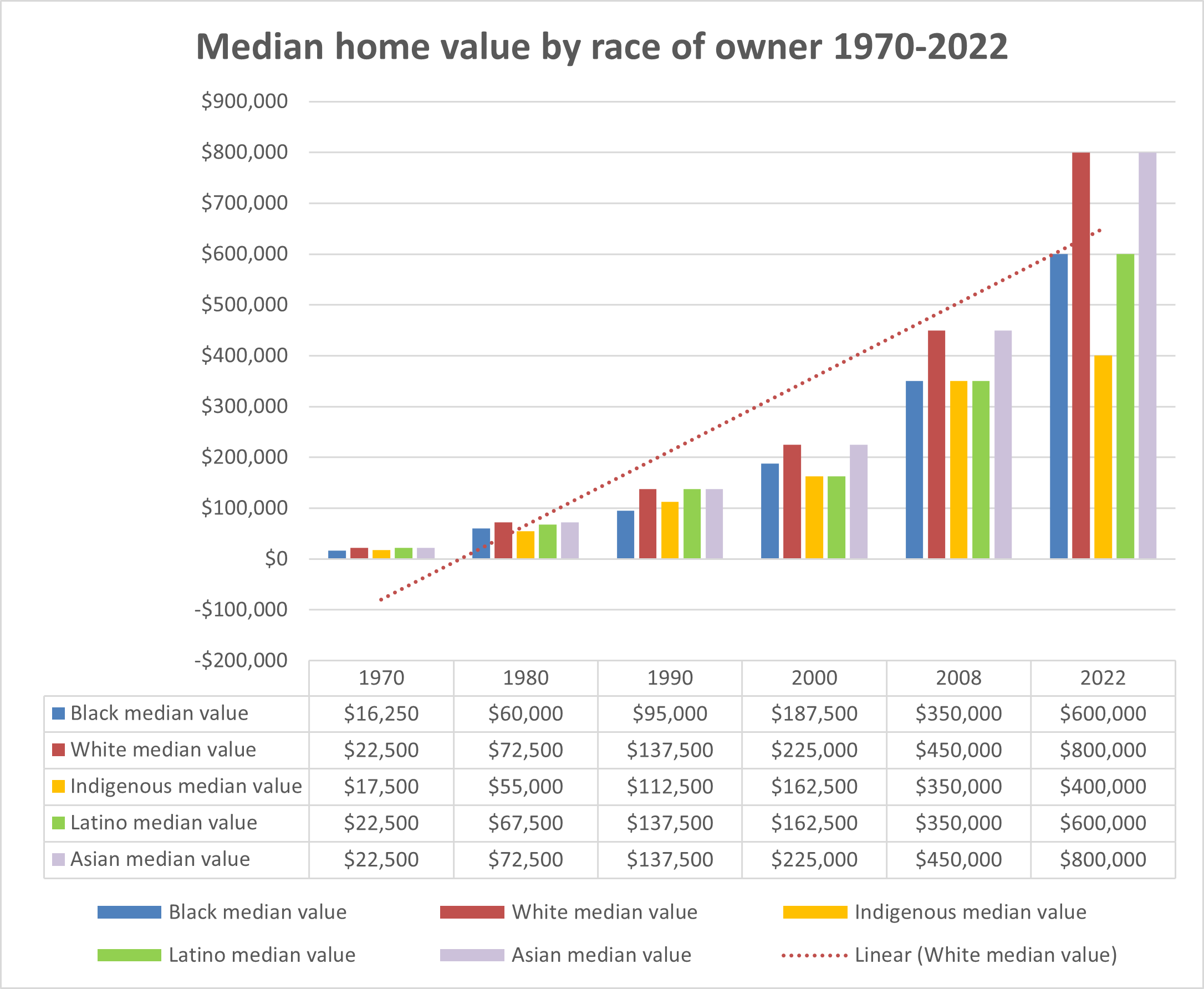

Median home prices by race Seattle/King County 1970-2022. Click to see more King County data. .

Median home prices by race Seattle/King County 1970-2022. Click to see more King County data. .

That fact helps explain the declining ownership rates of Black families. The chart at right shows the exponential increase in property values since 1970 in King County. Think about what that meant for families who had been locked out of the housing market. In 2022, the median home in King County was valued at more than 35 times as much as in 1970 ($790,000/$22,500 = 3511%). This far exceeded overall inflation and the rate of increase in family incomes (940%). A family selling a full-valued home could take advantage of this rocketing market, exchanging one house for another or dispersing housing assets through inheritance. But a family trying to buy for the first time in the post-restriction decades (and those selling undervalued homes) needed much higher incomes to buy property.

Especially since the 1990s, home buying has required different resources than it did in the golden age of mass homeownership after World War II (1940-1970) when Federal Housing Authority (FHA) assistance helped most White families become homeowners. Buyers have needed wealth to get started; wealth in the form of inheritance or high-paying jobs. Highly paid business-class and professional-class migrants from California, New York, and across the Pacific have been able to join this pricey housing market, while those with modest incomes and without family property wealth have lost out.

Daylighting restrictions

While their shadow continues to shape housing opportunities, the covenants themselves have been largely forgotten until recently. Title companies usually do not report them in the title insurance reports they provide buyers when a property is changing hands. As a result, most residents know little about the instruments of exclusion and segregation that may be part of their neighborhood history.

Starting in 2005, the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project began to document and expose what had been hidden and forgotten. Locating property restrictions was difficult. With no digital records available, we sampled microfilm copies of deeds and documents in the King County Recorders Office and County Archives. This was the first significant effort in any major city in the United States and as we published initial results it drew attention, both in news media and from the Washington legislature which passed in 2006 the first of four state laws inspired by our findings. That initial online database of restrictive covenants also inspired similar projects at universities and in cities across the country which now coordinate through the National Covenants Research Coalition.

Some counties have not had the funds to digitize property records. The UW and EWU teams searched the volumes one page at a time, looking for racist clauses

In May 2021, the Washington legislature passed HB 1335 supporting this project and charging our team at the University of Washington and the team at Eastern Washington Univerity with identifying and mapping neighborhoods covered by racist deed provisions and restrictive covenants across the state.

To fulfill this requirement we have searched an estimated 7 million documents with the help of county auditor/recorder offices. Some records were already in digital format, allowing our software experts to conduct computer searchs for restrictive terms. With the cooperation of the King County Archives we scanned more than one million records ourselves. But for some counties we needed to look through original records in bound volumes maintained in county offices.

Even for digital records, computers can only do some of the work. Suspect documents need to be confirmed and data recorded. Fortunately, we have been aided in these tasks by more than 1,900 community volunteers who joined the effort after hearing public presentations by student members of our staff.

To date the project has identified documents covering nearly 80,000 properties. We report results for 16 counties in western Washington: King, Pierce, Snohomish, Thurston, Kitsap, Clark , Cowlitz, Island, Skagit, Mason, San Juan, Whatcom . We found few racial restrictions in the property records of Grays Harbor, Jefferson, Lewis, and Skamania counties. The Eastern Washington University team is handling eastern counties. Follow the link below to see maps for all counties. We will report further results as we can.

Further reading

"Enforcing Neighborhood Segregation in Seattle: The History of Seattle Covenants" by Catherine Silva

"Segregated Seattle," Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project

Mapping Prejudice: Visualizing the Hidden Histories of Race and Privilege in the Built Environment, University of Minnesota

Dividing the City: Race-Restrictive Covenants in St. Louis and St. Louis County, University of Iowa

Mapping Segregation in Washington D.C.

Patchwork Apartheid: Private Restriction, Racial Segregation, and Urban Inequality by Colin Gordon (Russell Sage Foundation, 2023)

Saving the Neighborhood: Racially Restricted Covenants, Law, and Social Norms by Richard R.W. Brooks and Carol M.R. Rose (Harvard University Press, 2013)

The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein (Liveright, 2018)

Excerpt from the list of restrictions in the homeowner's association bylaws for Blue Ridge, one of several neighborhoods in northwest Seattle and Shoreline developed and restricted by airplane industrialist William Boeing

Excerpt from the list of restrictions in the homeowner's association bylaws for Blue Ridge, one of several neighborhoods in northwest Seattle and Shoreline developed and restricted by airplane industrialist William Boeing This image from the brochure advertising properties for sale in the Shoreline community of Innis Arden assured would-be buyers that it was a "restricted community."

This image from the brochure advertising properties for sale in the Shoreline community of Innis Arden assured would-be buyers that it was a "restricted community." Example of a restriction embedded in the plat itself. Click for readable copy.

Example of a restriction embedded in the plat itself. Click for readable copy. Examples of restrictive covenants.

Examples of restrictive covenants.

This 1948 story in the New World, a weekly associated with the Washington Commonwealth Federation and the Communist Party, helped push the campaign to resist racial restrictive covenants.

This 1948 story in the New World, a weekly associated with the Washington Commonwealth Federation and the Communist Party, helped push the campaign to resist racial restrictive covenants. As the Supreme Court heard arguments in the Shelley case, the New World began to profile the problem in Seattle

As the Supreme Court heard arguments in the Shelley case, the New World began to profile the problem in Seattle 2020 distribution of African Americans in King County. This is one of the dozens of maps showing race and segregation for Black, Asians, Hispanics, Indigenous, and White persons in Washington counties 1940-2020.

2020 distribution of African Americans in King County. This is one of the dozens of maps showing race and segregation for Black, Asians, Hispanics, Indigenous, and White persons in Washington counties 1940-2020.