Kitsap County, located on the western shores of the Puget Sound, has long held strategic importance in Washington State’s military and economic landscape. With the establishment of the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard (PSNS) in Bremerton in 1891, the county was set to become a center of naval power and shipbuilding activity. The shipyard’s expansion during World War I and World War II transformed Bremerton and surrounding cities into booming hubs of the wartime industry, drawing workers from across the country including the first significant population of African Americans.[1] Yet opportunity and exclusion went hand in hand, and while Kitsap County welcomed new residents during times of industrial growth, it also employed formal and informal mechanisms to segregate, displace, and marginalize communities of color. From racially restrictive covenants and zoning policies to community-level resistance and resilience, the region’s history is one of both structural racism and grassroots resistance. Through the stories of Suquamish land dispossession, Sinclair Park, Chinese exclusion, and postwar Black displacement, one can place restrictive covenants within the wider system of racial and geographical control.[2]

Indigenous Removal and Early Racial Segregation

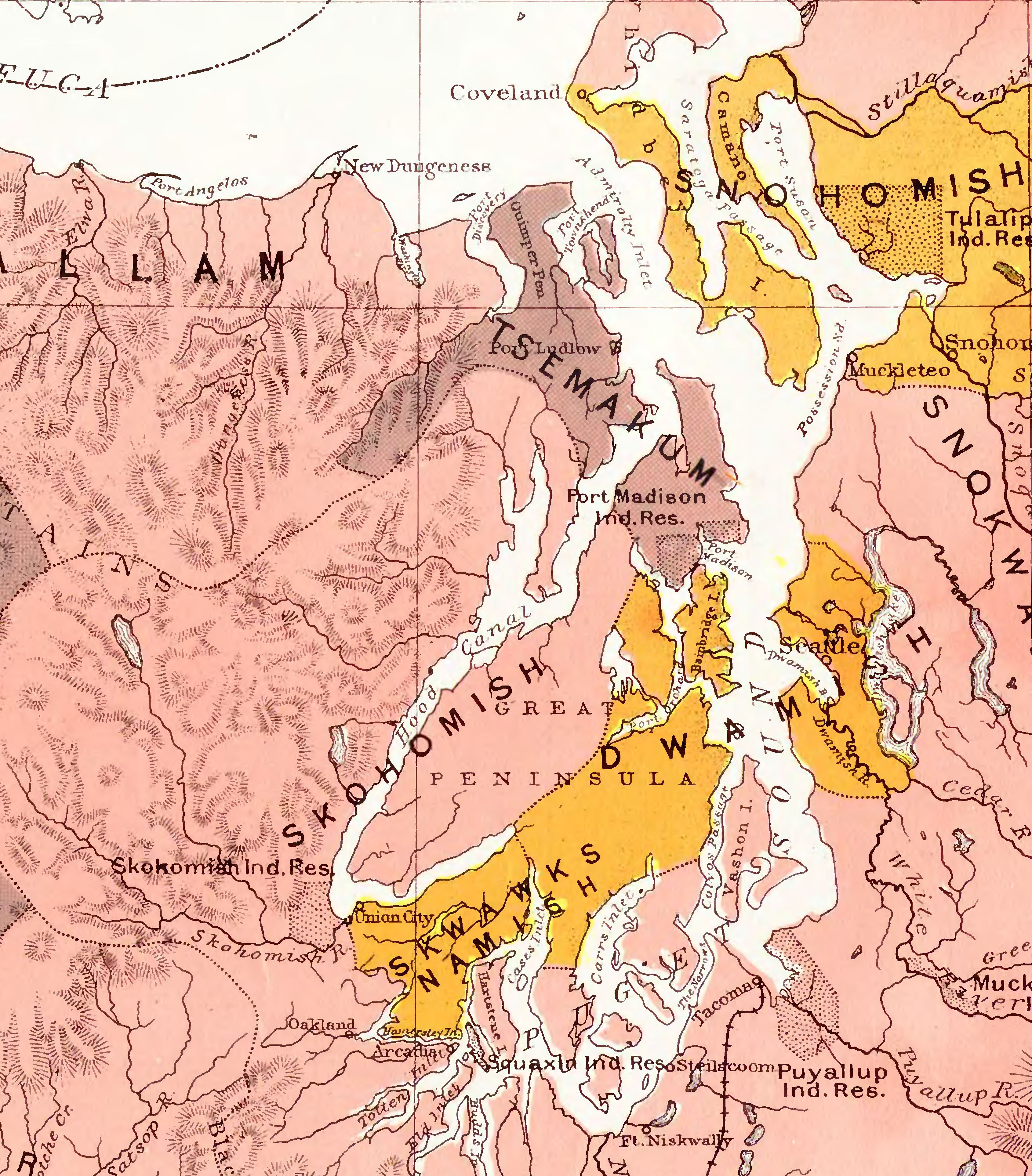

Before the United States seized the area, what would later become Kitsap County was home to Indigenous communities, including the Suquamish people, who lived on land along Dyes Inlet and other waterways. The Skokomish and the S’Klallam peoples lived further north.[3] In the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott, all were forced to cede most of their land to white settlers. The Suquamish were supposed to relocate to the Port Madison Reservation on Bainbridge Island. Though some Native people remained in mill towns or worked in logging and fishing, the transition from land-based autonomy to dependency on wage labor marked the beginning of racialized displacement in the region.[4] White settlers quickly claimed land under federal distribution programs, and lumber companies established mills at Port Orchard, Port Gamble, and Port Blakely, shipping wood products to build California’s growing cities.

By the late 1800s, labor migration introduced new racial dynamics. Chinese workers, many stranded after the transcontinental railroad’s completion, found work in Kitsap’s logging camps and laundries. However, widespread anti-Chinese violence and exclusionary laws, including the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, led to systematic expulsions of Chinese workers from Kitsap’s mill towns by the 1890s. By 1900, only 51 Chinese residents remained in Kitsap County.[5]

Japanese immigrants began arriving shortly thereafter, initially taking jobs in timber and agriculture and then operating their own farms. Many settled on Bainbridge Island, specializing in growing strawberries. By 1920, Kitsap County’s Japanese population had grown to 105 individuals, and by 1940 it reached approximately 276, concentrated around Bainbridge Island, Port Orchard, and Silverdale. State-level alien land laws in the 1920s prohibited Japanese immigrants from owning property, forcing many families to place land in the names of U.S.-born children or rent from white owners. During World War II, Executive Order 9066 led to the forced removal and incarceration of all Japanese Americans from Bainbridge and others from elsewhere in Kitsap County, with many never returning.[6]

One striking case was that of Takuji Yamashita, a Japanese immigrant who graduated from the University of Washington Law School in 1902. Although he passed the oral bar exam, he was denied admission to practice law in Washington because he was not considered “white” under federal naturalization laws. The Washington State Supreme Court upheld this decision, excluding Yamashita from a legal career despite his qualifications.[7] His story illustrates how laws enforced racial boundaries, dictating both where people could live and what professions they could enter.

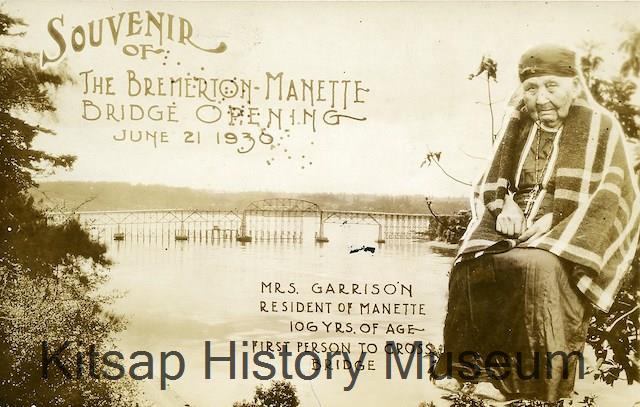

African American residents arrived in Kitsap County in small numbers through naval service and labor migration. In 1860, the census listed five Black men, including John Garrison, a lumberman whose Native American partner, Piapach, became a civic symbol when she rode across the Manette Bridge during its dedication.[8] Piapach’s public act stood as a rare symbol of Indigenous and Black presence in a white-dominated civic space. But few Black Americans followed Garrison, even as shipbuilding during World War I drew white workers to the area. The 1930 census recorded only 104 Black residents in Kitsap County. It was not until the wartime labor mobilization of the 1940s that Kitsap’s Black population began to grow substantially.[9]

Wartime Migration and the Construction of Segregation

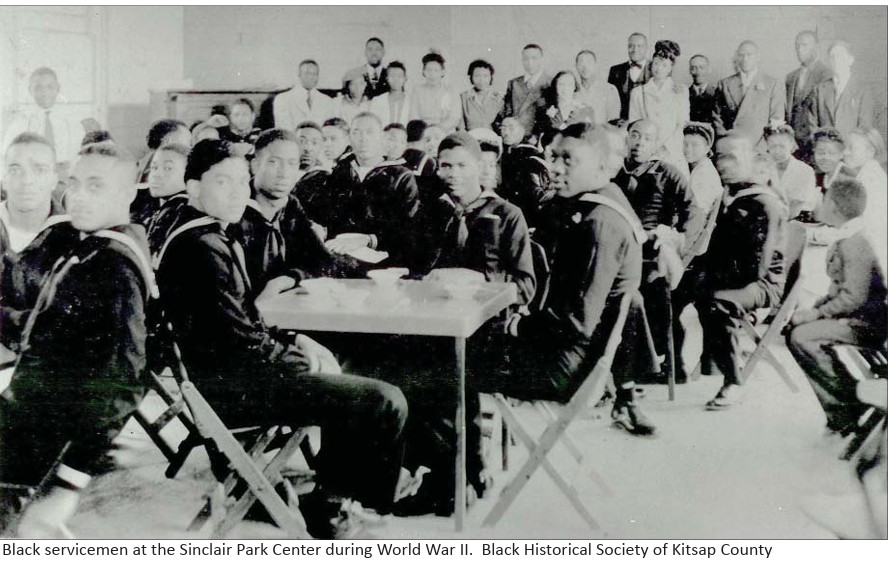

The Second World War caused an unprecedented demographic transformation in Kitsap County. Driven by naval construction and wartime contracts, Bremerton’s population exploded from 15,000 to over 35,000 in just five years.[10] Most of the newcomers were white, but some Asian, Indigenous, and Latinx Americans, and a large number of African Americans from the South and Midwest were drawn by shipyard jobs. By 1945, the Black population of Bremerton and Kitsap County was estimated at 4,500, up from only 118 just five years earlier.[11] Yet while federal labor needs demanded Black workers, local institutions and industries often resisted integration. Unions like the Aeronautical Mechanics Union (IAM) and employers like Boeing Aircraft stonewalled Black and women workers despite Roosevelt’s 1941 executive order for fair employment practices.[12] The Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and other ship building operations complied with the fair employment orders and hired Black workers, though mostly into the least desirable positions.

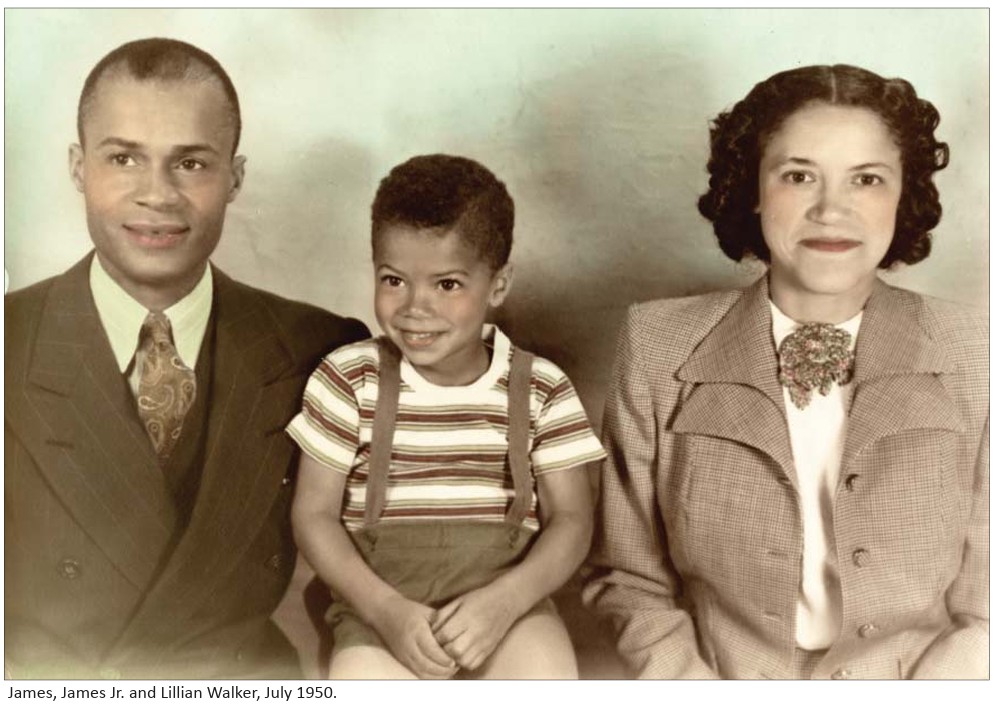

"Bremerton was a white supremacist town," explained Lillian Walker in an autobiography co-authored with John C. Hughes. "I'd never experienced anything in Illinois like we encountered when we came here." She had moved west with her husband James to work in the shipyards in 1941. Incidents of sudden and unwarranted attacks by gangs of whites were common. “One morning, utterly without provocation, two sailors jumped James Walker” just outside a movie theater where the couple worked a second job as janitors.[13]

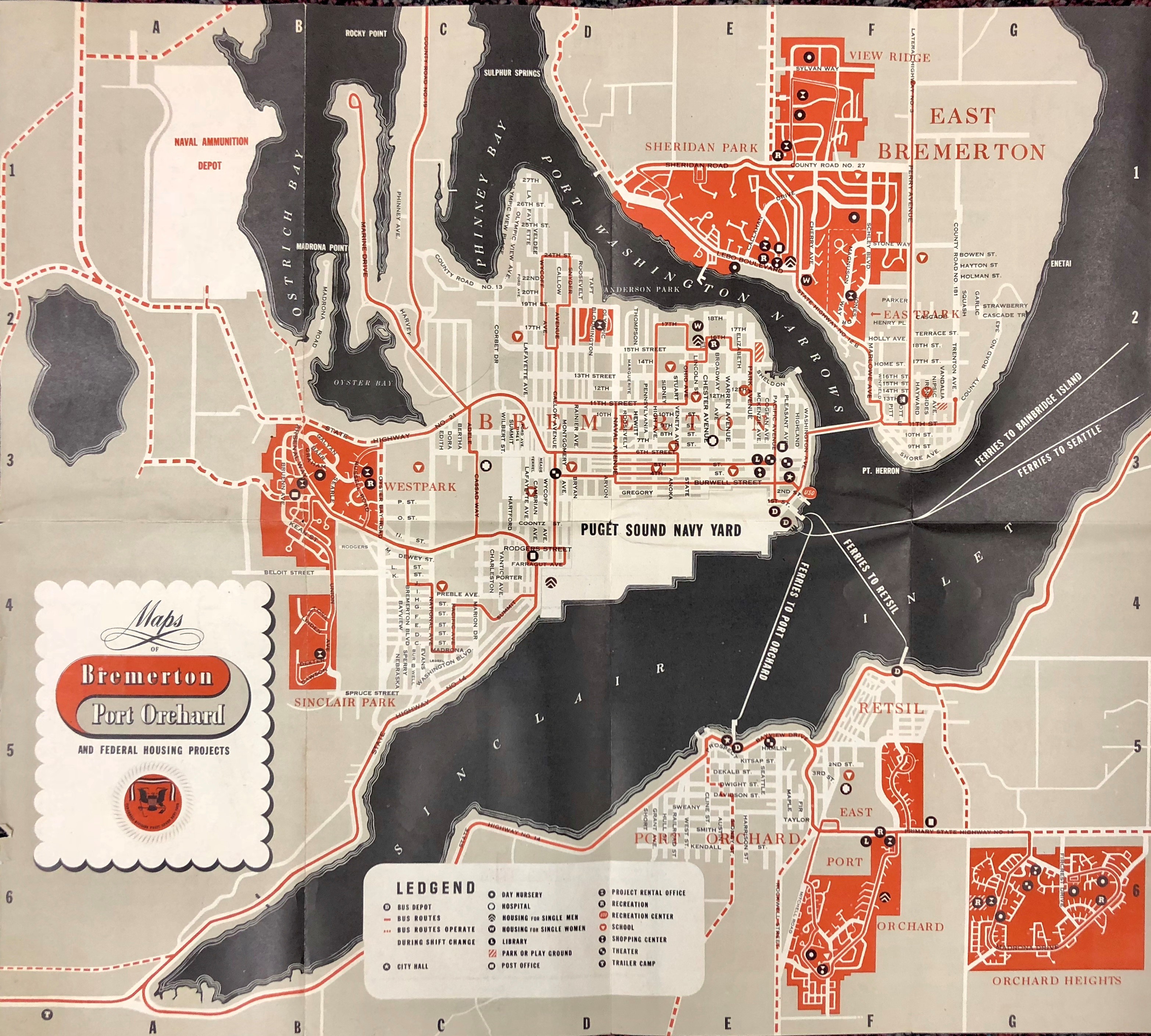

Black Navy personnel and war workers were excluded from most restaurants, bars, barber shops, and other establishments, many of which prominently displayed “Whites Only” signs. Housing was equally difficult. Bremerton’s shipyard operated around the clock, but existing housing was far from adequate for the sudden influx of workers and families. The federal government rushed to build new housing, leading to segregated developments managed by the Bremerton Housing Authority (BHA), established in 1940. Black families were steered into Sinclair Park, while white residents occupied projects like Westpark or Sheridan Park. The BHA also enforced discriminatory policies against Asian immigrants, even excluding Taiwanese families based on assumptions of “foreign” status.[14]

Though Sinclair Park was constructed as temporary wartime housing, the community that grew there was anything but transient. Residents formed deep social bonds and established significant cultural and civic institutions. Sinclair Park became home to local chapters of the NAACP, the Carver Club, and Elks chapters. The Sinclair Park Community Center, designed by the Seattle architectural firm NBBJ, emerged as a vital social and civic hub, offering educational programming, youth oratorical contests, neighborhood events, and religious services.

One of the most notable stories is that of Quincy Jones, who lived in Sinclair Park as a child and discovered music on a piano in the community center. He later described the experience as transformative: “That piano changed my life,” he said. “That was where the music first hit me.”[15] Another resident, Marie Greer, was an active participant in civic life, helping to organize plays, oratorical contests, and neighborhood activities that gave young Black children a sense of purpose and community pride.[16]

The community was also deeply political. On May 23, 1943, local activists and community members formed the Bremerton branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), led by Reverend Chester Cooper. Founding members included Lillian and James Walker, Al and Hazel Colvin, Elwood and Marie Greer, Loxie and Alyce Eagans, and others. They used the NAACP as a platform to fight segregation and discrimination in both housing and employment. “We talked to people in Seattle that were in charge. We knew that we needed help,” Lillian Walker recalled. “It was just more than two or three of us that were fighting by ourselves.”[17]

The Bremerton NAACP later gave rise to the Carver Civic Club, a civil rights organization for Black women that still exists today.[18] The years following World War II also saw rising local civil rights activism and resistance to racial barriers. In 1947, Bremerton’s Black community organized a mass protest against the exclusion of African Americans from local taverns, an early example of direct-action civil rights protests in the county. [19]

Restrictive Covenants Across Kitsap County

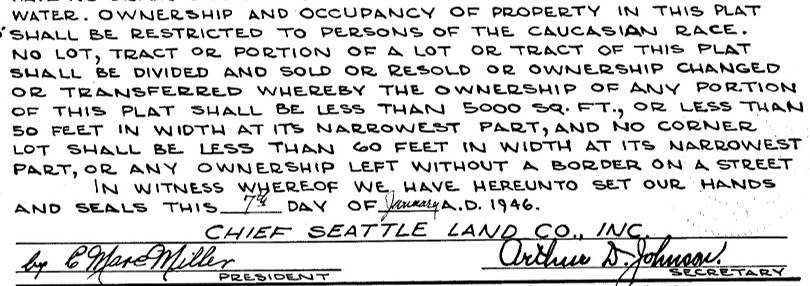

Restrictive covenants were legally binding agreements in property deeds barring individuals from buying, renting, or occupying homes based on race, religion, or national origin. Recorded with county authorities, these documents imposed conditions on future owners and were meant to forever restrict who could buy, rent, or occupy the property. They were enforceable in court. Neighbors could challenge a sale or rental that violated the racial rules and get it reversed, at which point the new owner/renter would be evicted and the seller could be held liable for substantial damages. These restrictions worked hand in hand with redlining policies and local zoning laws to create racially exclusive neighborhoods.[20]

In Kitsap County, the first known restrictive covenants appeared in the 1920s, targeting waterfront properties and scenic developments. By the 1930s and 1940s, restrictive language had spread to subdivisions in Bremerton, Port Orchard, and Bainbridge Island.[21] Deeds across Kitsap neighborhoods often barred “Blacks,” “Orientals,” or “anyone not of the Caucasian race” from ownership or occupancy.[22]

The Racial Restrictive Covenants Project’s maps reveal clusters of these covenants in East Bremerton, near Rolling Hills Golf Course, Lions Park, and throughout neighborhoods like Sheridan Park and Navy Yard City. On Bainbridge Island, restrictive covenants were attached to residential tracts near Wing Point and Rolling Bay. The covenant texts often used identical language, reflecting how developers and real estate firms coordinated to keep neighborhoods racially exclusive.[23]

Prominent Restrictors in Kitsap County

James W. Carr was one of the earliest restrictors, active in the 1920s and 1930s. His name appears on deeds in East Bremerton subdivisions that barred occupancy by anyone “not of the Caucasian race.”

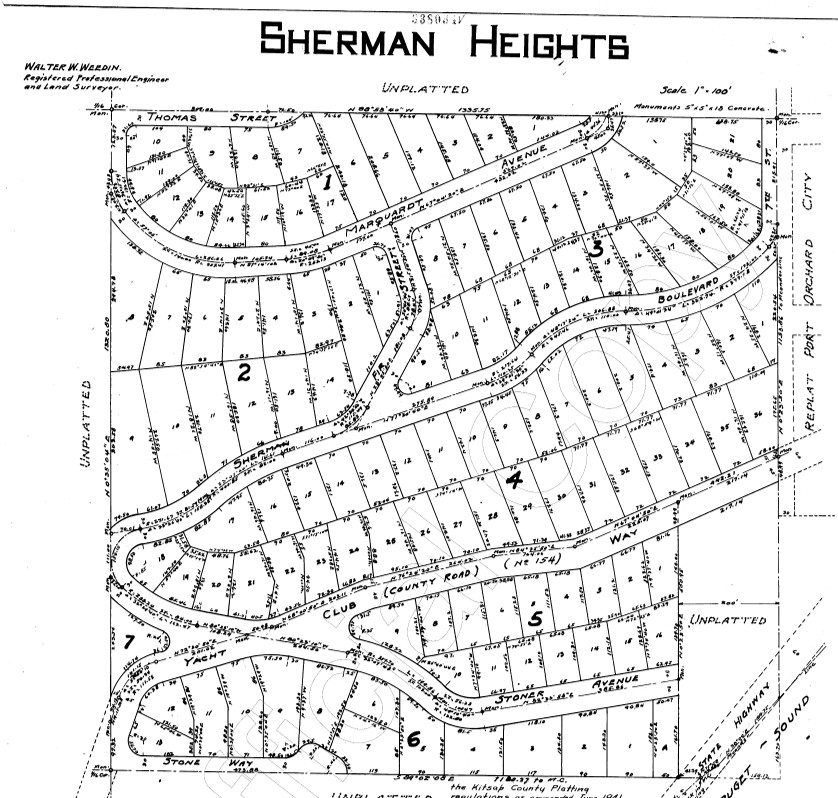

Fred and Charlotte Sherman also imposed early racial restrictions in Bremerton, filing deeds prohibiting property sales or leases “except to persons of the white or Caucasian race.” They were involved in property platting during Bremerton’s early suburban expansion, contributing to the county’s initial wave of racially exclusive housing.

Emma McDonald is documented as a restrictor in the 1930s, adding covenants in small subdivisions around Manette and East Bremerton.

In the 1940s, as Kitsap County’s population surged during wartime, new major restrictors emerged. Fulmer and Company became one of the most prolific restrictors, placing covenants particularly in East Bremerton. Their deeds prohibited occupancy by “anyone other than of the white or Caucasian race,” a formula echoed in numerous Kitsap neighborhoods, including Sheridan Park and Navy Yard City.

Island Lake Park Development Company imposed racial restrictions in subdivisions around Silverdale and Island Lake, using nearly identical language barring nonwhite residents. The covenant maps show significant clusters tied to this developer’s projects.

Port Blakely Mill Company was historically a lumber company and landowner on Bainbridge Island. As the timber economy shifted toward residential development, Port Blakely imposed covenants that shaped Bainbridge’s racial geography well into the postwar years.

The last restrictions we have found in Kitsap County date from 1948. That year, Island Lake Park Development Co., Port Blakely Mill Co., and Chief Seattle Land Co. all recorded covenants, marking the end of formal covenant writing in the county. Our research in subsequent years was limited so there may have been restrictions added in the 1950s, but the practice became less common after the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1948 ruling in Shelley v. Kraemer. The decision instructed courts to no longer enforce restrictive covenants, but the restrictions themselves remained legal until 1968 when Congress passed the Fair Housing Act.

These developers’ actions were not isolated. Instead, they were part of a larger network of real estate firms, title companies, and homeowner associations that institutionalized racial exclusion across Kitsap County. The language of these deeds, often identical from one subdivision to the next, demonstrates how widespread and systematic these practices were.

Dismantling Sinclair, Displacing Community

By 1950, Sinclair Park was marked for closure. Its units were auctioned off and floated across Puget Sound to become summer cabins. The land was transferred to the National Guard. By 1960, Kitsap’s Black population had dropped to 1,243, about one fourth of the peak population of 1945.[24] The community center, once a nucleus of civic life, was converted into a military facility and eventually demolished. One of Kitsap’s most important Black spaces vanished from the map.[25]

This erasure was intentional. County officials knew they were dismantling a community and pushing Black residents out. Sinclair’s demolition displaced families and erased a vibrant Black wartime community from public memory. Today, contemporary art projects and museum exhibits are working to restore this legacy, preserving oral histories and family archives.[26] The absence of Sinclair in urban planning documents illustrates how exclusion can persist not only through action but through deliberate omission. Without preservation efforts, places like Sinclair risk becoming invisible, leaving future generations unaware of the networks and stories once rooted there.

As Black Americans left Kitsap, Filipinos, some connected to naval service and others working in agriculture, began to increase their presence. They numbered 604 in 1960. Some Japanese Americans (271) returned after internment, and the Indigenous population reached 745. Nevertheless, the county remained 96.5% white in 1960.[27]

Even as Sinclair Park disappeared, Kitsap residents of color continued to press for change. In 1953, Reverend Chester Cooper, a leader of the NAACP, led efforts to challenge segregation in public spaces and employment. Community organizing persisted throughout the decade, laying groundwork for later open housing campaigns and civil rights advocacy.[28] In 1963, the Kitsap County Council for Human Rights was established, making it one of the earliest county-level human rights councils in Washington State. This council became instrumental in investigating discrimination complaints and advising local government on civil rights issues.[29] Yet even as laws changed, “gentlemen’s agreements” and redlining persisted in Bremerton and elsewhere in the county for decades. Lillian Walker of the NAACP recalled real estate men trying to steer Black families to buy homes only along the Sinclair Inlet, where most Black families lived.[30]

Legacy and Ongoing Inequity

The legacies of exclusion and segregation remain visible across Kitsap County, with continuing disparities in housing and economic opportunity for communities of color. The county population has grown steadily in the decades since the 1960s and the percentage of nonwhite persons has increased as well. 96% white in 1970, the 2020 census found almost 25% of residents claiming other identities, especially Hispanic/Latino, Asian, and “two or more races.” Black and Indigenous populations had grown more slowly, comprising 2% and 1% respectively.[31]

Segregation maps indicate housing patterns in many historically white neighborhoods have remained largely unchanged and Opportunity Index scores remain lowest in historically diverse neighborhoods, revealing disparities in education, health, and transportation access.[32]

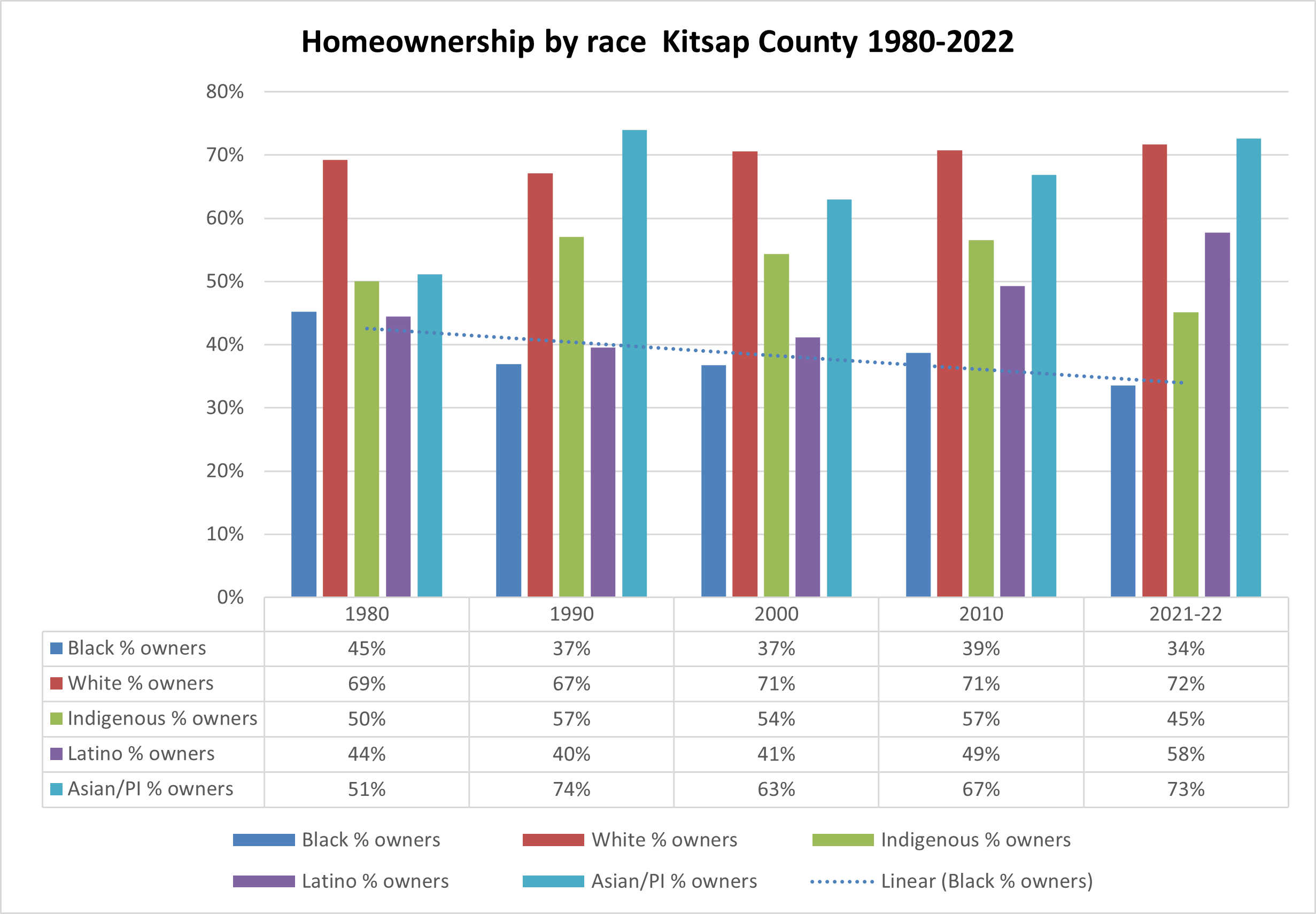

Homeownership rates reported by this project show in stark terms the continuing effects of racial restrictive covenants, redlining, and other racist housing practices. In the most recent data from 2022, 72% of White households owned their homes while only 34% of Black households were homeowners. The rate for Indigenous families (45%) and Latino families (58%) were somewhat better, while Asian families (73%) matched the rate for Whites.

Conclusion

The racial restrictive covenant maps of Kitsap County are more than archival documents; they are mirrors reflecting the deliberate shaping of neighborhoods by race. From Suquamish dispossession to the vibrancy and eventual dismantling of Sinclair Park, these maps and the stories behind them illuminate a layered history of exclusion and resilience. The Racial Restrictive Covenants Project has revealed just how systematic and widespread these restrictions were, offering vital tools for reckoning with the county’s past.

Looking at these maps helps us understand why racial inequalities persist today. Neighborhoods were not formed solely by chance or individual choice but often through deliberate acts of exclusion. Confronting this legacy calls for concrete action: investing in historically marginalized neighborhoods, reforming zoning laws to allow more diverse housing, and preserving stories like those of Sinclair Park. Only by recognizing how the past shapes the present can Kitsap County move toward genuine equity and inclusion for all its residents.

[1] Fredi Perry, Bremerton and Puget Sound Navy Yard (Bremerton, WA: Perry Publishing, 2002), 3–4.

[2] Perry, Bremerton and Puget Sound Navy Yard, 3-4.

[3] Perry, Bremerton and Puget Sound Navy Yard 3.

[4] Perry, Bremerton and Puget Sound Navy Yard 4.

[5] Perry, Bremerton and Puget Sound Navy Yard 7-9.

[6] Nicole Grant, “White Supremacy and the Alien Land Laws of Washington State,”, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. https://depts.washington.edu/civilr/alien_land_laws.htm

[7] Perry, Bremerton and Puget Sound Navy Yard 180.

[8] Perry, Bremerton and Puget Sound Navy Yard 6.

[9] Perry, Bremerton and Puget Sound Navy Yard 6.

[10] Washington State Census Board, Population Trends: Towns and Cities of Washington State: April 1, 1940 to February 1, 1945 (Seattle: Washington State Census Board, 1946).

[11] John Caldbick, “Bremerton – Thumbnail History,” HistoryLink.org https://www.historylink.org/file/9583

[12] Sarah Davenport, “The Battle at Boeing: African Americans and the Campaign for Jobs 1939-1942,” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project https://depts.washington.edu/civilr/boeing_battle.htm

[13] Lillian Walker, Washington State civil rights pioneer : a biography & oral history (Olympia: Washington State Legacy Project, Office of the Secretary of State, 2010) http://finditconsumer.wa.gov/legacy/stories/lillian-walker/

[14] Gabriel Spitzer, “Bremerton’s segregated wartime housing project,” KNKX Public Radio, January 11, 2020. https://www.knkx.org/other-news/2020-01-11/bremertons-segregated-wartime-housing-project-hosted-a-vibrant-african-american-community

[15] Bremerton Housing Authority. “Sinclair Park: Bremerton ’s African American Wartime Community.” August 2023. https://bremertonhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Kitsap_Black_History_Article_re_Sinclair_Park.pdf.

[16] Kitsap History Museum. “Black Trailblazers of Kitsap.”. https://kitsapmuseum.org/black-trailblazers-of-kitsap/.

[17] Lillian Walker, Washington State civil rights pioneer

[18] Kitsap History Museum. “Black Trailblazers of Kitsap.”

[19] Kitsap County Council for Human Rights. Kitsap County Timeline of Human Rights. November 1, 2021.

[20] City of Port Orchard. Port Orchard Racially Disparate Impacts Analysis 2020 Report. Port Orchard, WA: City of Port Orchard, 2020

[21] Port Orchard Racially Disparate Impacts Analysis 2020 Report.

[22] Kitsap History Museum. Historical Context Statement. May 2022. https://kitsapmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/historyical-context_3.pdf.

[23] Racial Restrictive Covenants Project Maps, University of Washington, https://depts.washington.edu/covenants/.

[24] Population data from National Historic Geographic Information System (IPUMS-NHGIS)

[25] Kitsap History Museum; HistoryLink. “File #9583.” https://www.historylink.org/file/9583

[26] David Vognar; Kitsap Sun. “Art as a History Lesson.” https://products.kitsapsun.com/archive/2004/02-22/407804_a_community_apart.html

[27] Population data from National Historic Geographic Information System (IPUMS-NHGIS).

[28] Kitsap County Council for Human Rights Timeline, 2021

[29] Kitsap County Council for Human Rights Timeline, 2021

[30] Legacy Washington. “Lillian Walker: Bremerton Civil Rights Pioneer.” http://finditconsumer.wa.gov/legacy/stories/lillian-walker/.

[31] For census population numbers see Mapping Race and Segregation in Kitsap County, Washington 1980-2020.

[32] Port Orchard Racially Disparate Impacts Analysis 2020 Report.