Snohomish County, like the rest of Washington State, has a long history of segregation and racial discrimination, dating back to the arrival of the first white settlers and continuing in the present day. Racial restrictive covenants, legally binding clauses in property records that prohibited all future owners from selling or renting the property to anyone other than a white person, were one tool used to promote segregation and exclusion. The language of these covenants was extremely explicit, and though some had termination dates, many were intended to ensure segregation of the property in question in perpetuity.

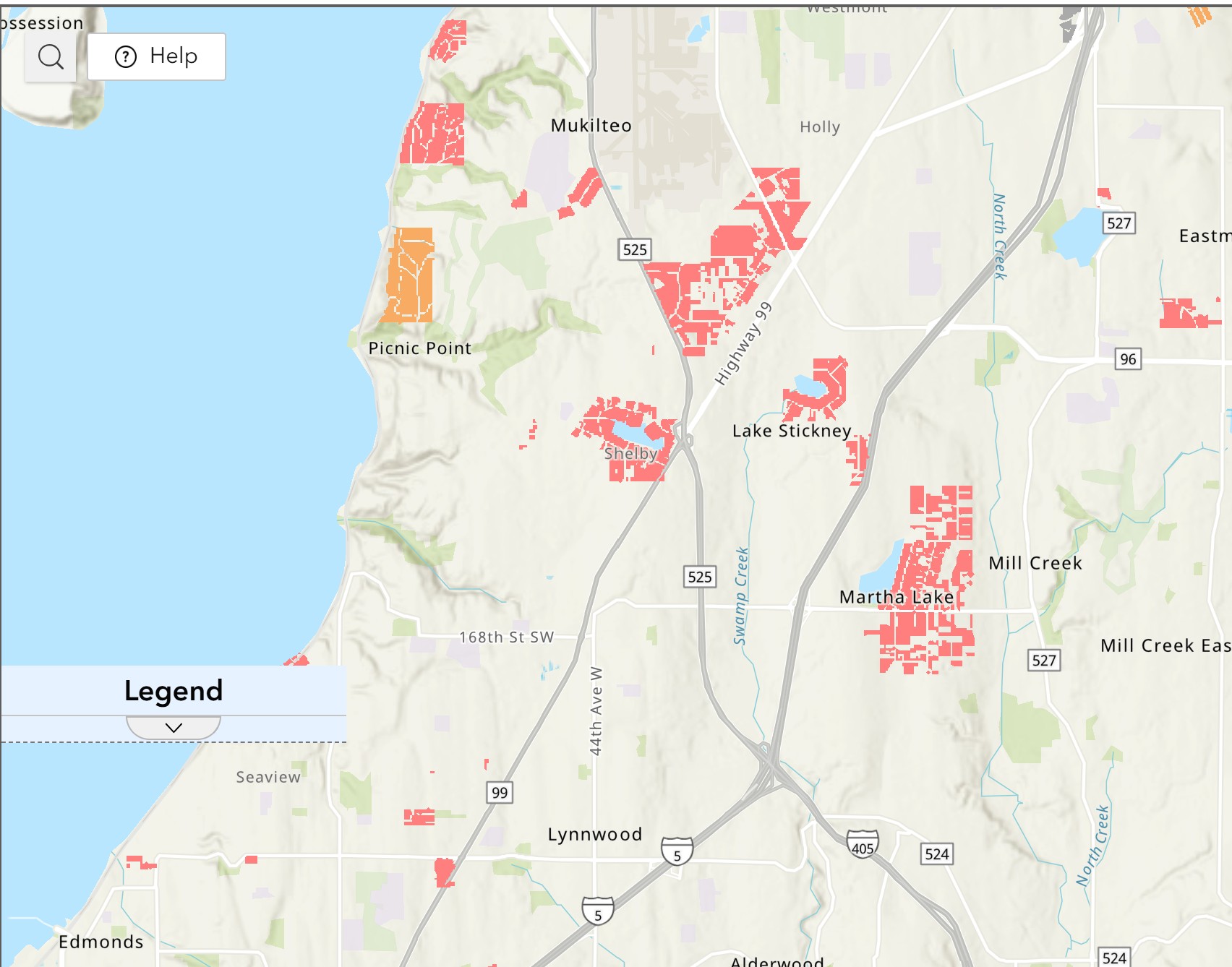

The Washington State Racial Restrictive Covenants Project has identified over 7,000 properties that were covered by such restrictions scattered throughout Snohomish County, the majority concentrated in the southwest part of the county across the line from Seattle and King County. The earliest documented restriction was applied in 1922, and they were prevalent in property records until discrimination in housing was made illegal by the 1968 Fair Housing Act. Though racial restrictions were widely used in the county, they were far from the only mechanisms of segregation and exclusion.

This essay details the history of racial restrictive covenants in Snohomish County alongside other forms of racial segregation and exclusion. In Snohomish County, the notion of exclusion is particularly salient because as late as 1970 the county population was 98% white. As this essay will demonstrate, the county’s whiteness was the result of active efforts to drive people of color out of the county and to make life difficult for those who remained.

Indigenous People and the Tulalip Reservation: Marginalization and Discrimination

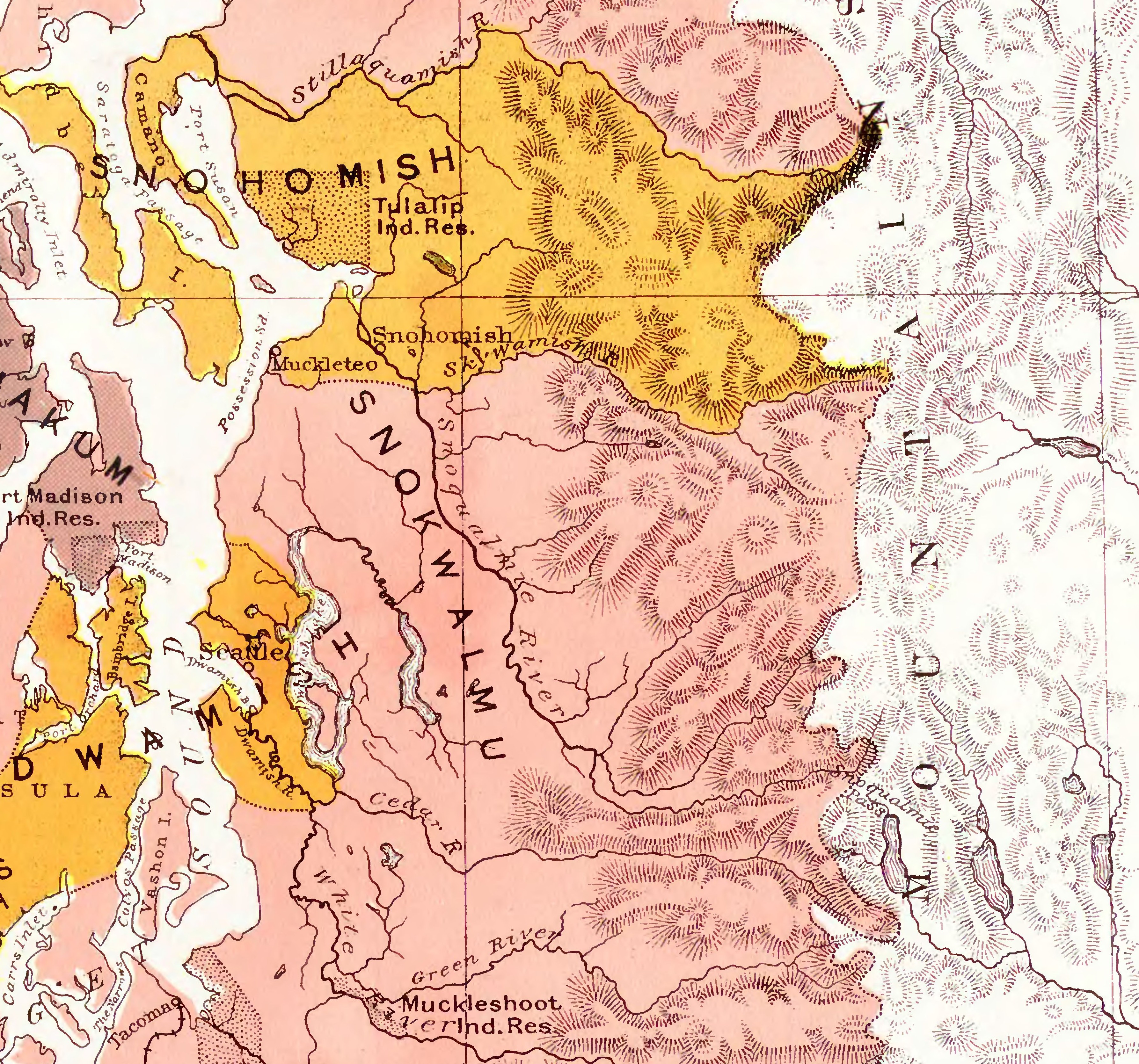

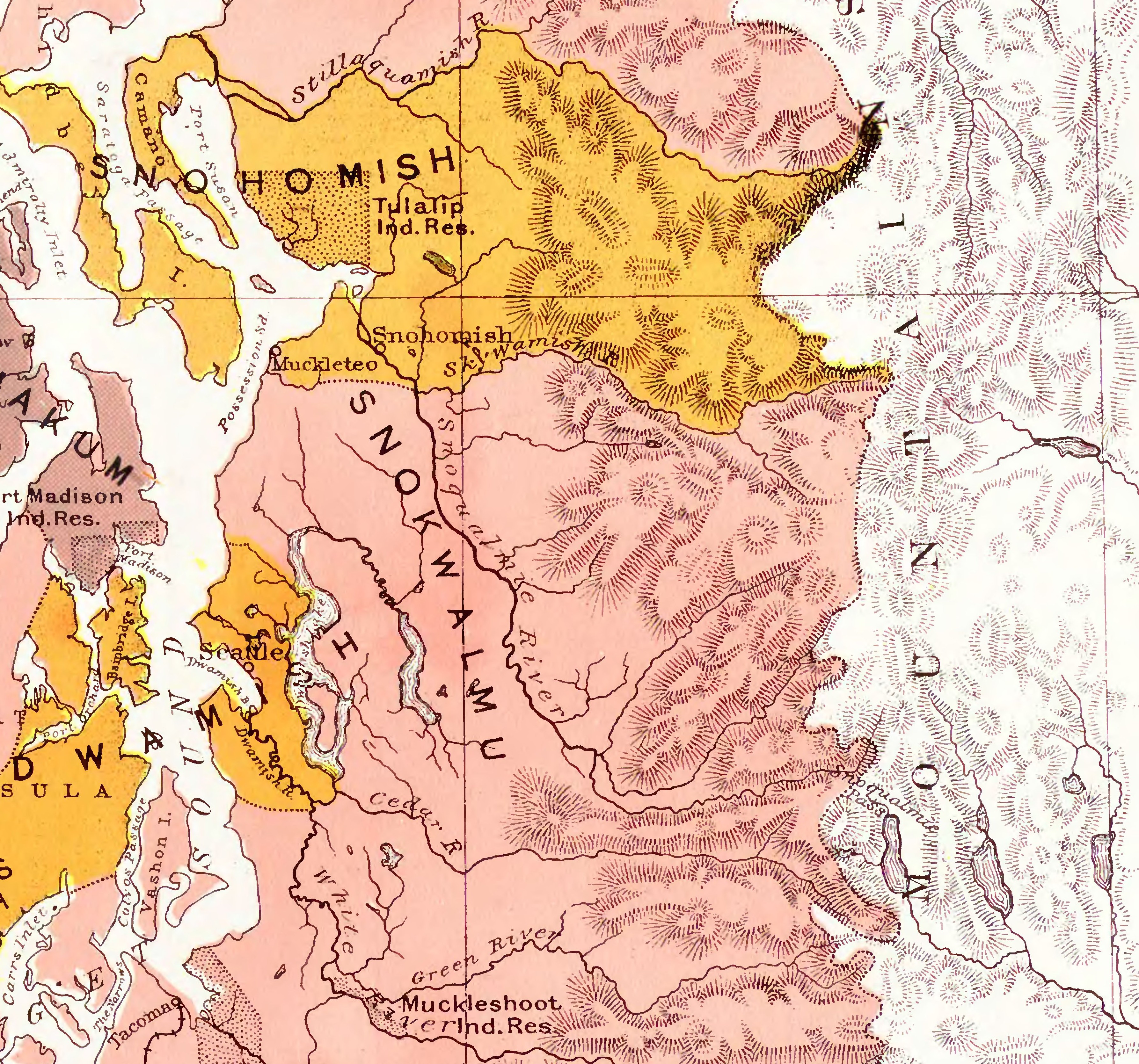

Detail from 1876 map by Department of the Interior shows tribal reservations and original tribal territories. Notice the the area designated for the Tulalip reservation. Decades later whites would be allowed to buy reservation parcels and even impose racist restrictions.

Detail from 1876 map by Department of the Interior shows tribal reservations and original tribal territories. Notice the the area designated for the Tulalip reservation. Decades later whites would be allowed to buy reservation parcels and even impose racist restrictions.

The earliest acts of racism and exclusion were committed by white settlers against the area’s indigenous inhabitants. The Snohomish, Skykomish, Snoqualimie peoples, along with other allied Coast Salish tribes, were confined to the 35 square mile Tulalip reservation through the 1855 signing of the Treaty of Point Elliott at Mukilteo. Tribes lost million of acres of land and waterways in the Puget Sound supposedly in exchange for the their right to self government and the preservation of traditional hunting and fishing rights.[1] Like other treaties between the U. S. government and indigenous peoples, these were empty promises.

In her memoir, Harriette Shelton Dover spoke of the poverty and hunger she experienced as a child growing up on the Tulalip reservation. “The white people who came here chose where they wanted to go. They took up a homestead and built a small house. They could farm. They had the choice. My parents and we Indian children-we had no choice, none whatever…we really were prisoners of war.”[2] This quote speaks to the harms wrought on indigenous people by the reservation system. Though this is a very different form of racial segregation and exclusion than the restrictive covenants that would begin to appear in the county in the 20th century, it too had the impact of excluding people of color from freedom to choose where and how they lived.

Harriet Shelton Dover (1904-1991) was the first woman elected to the Tulalip Tribal Council. Tulalip, From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community, was published after her death. In this photo (courtesy Tulalip Tribes & HistoryLink) she is wearing a cedar dress.

Harriet Shelton Dover (1904-1991) was the first woman elected to the Tulalip Tribal Council. Tulalip, From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community, was published after her death. In this photo (courtesy Tulalip Tribes & HistoryLink) she is wearing a cedar dress.

Dover also reported facing employment discrimination when she sought work off the reservation in Marysville as an adult in the 1950s. She remembers inquiring about a dishwashing job and being told there were no openings and to never come back, though she knew there was an opening and knew the woman they ultimately hired. She also recalls an incident where, when she arrived at a job interview, the personnel director got up and left when she saw her coming and refused to even speak to her.[3] She sums up these experiences: “So much for income. There was no chance to find work, to go to work, and to have regular work. Most people would not hire an Indian.”[4]

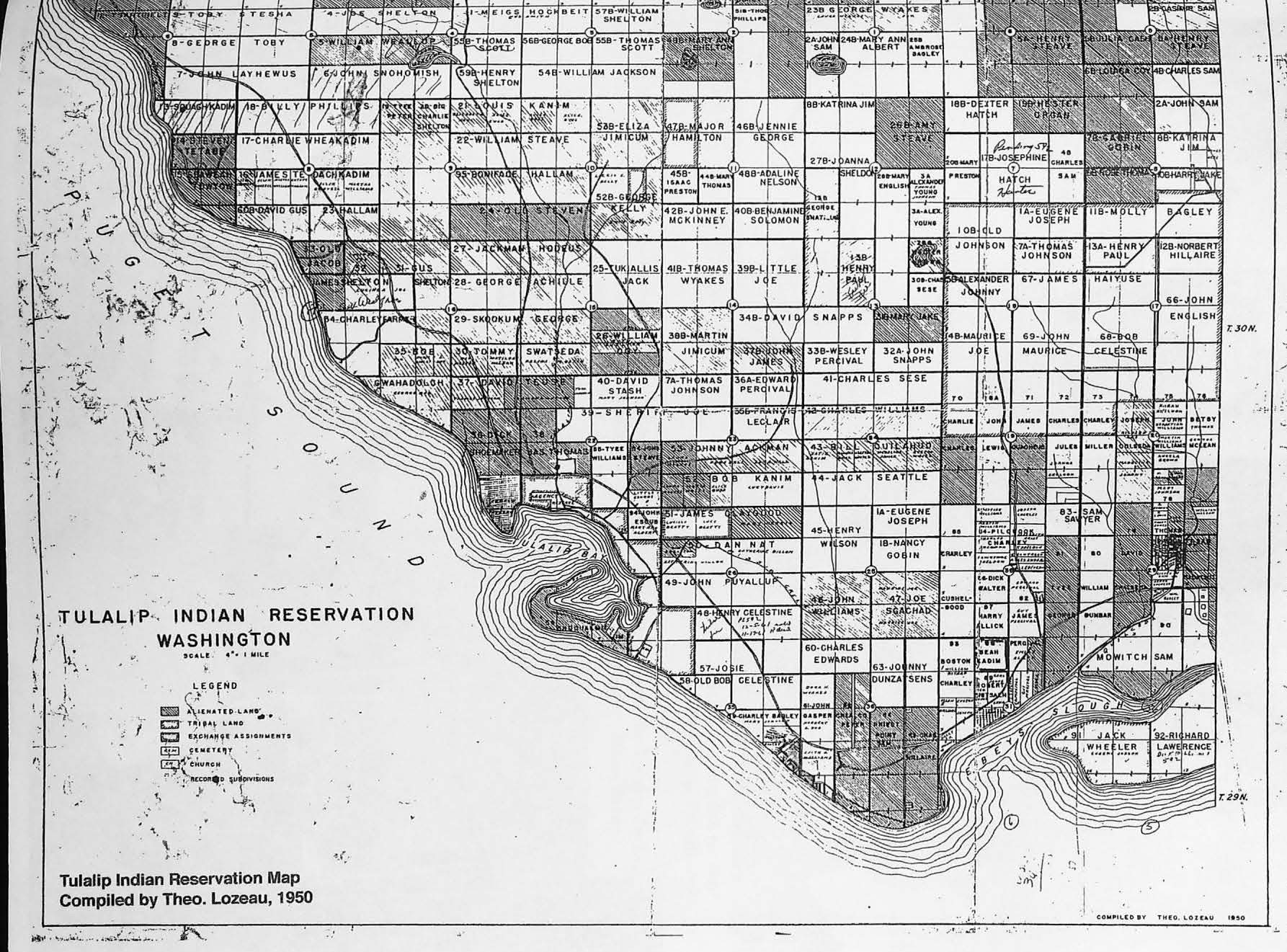

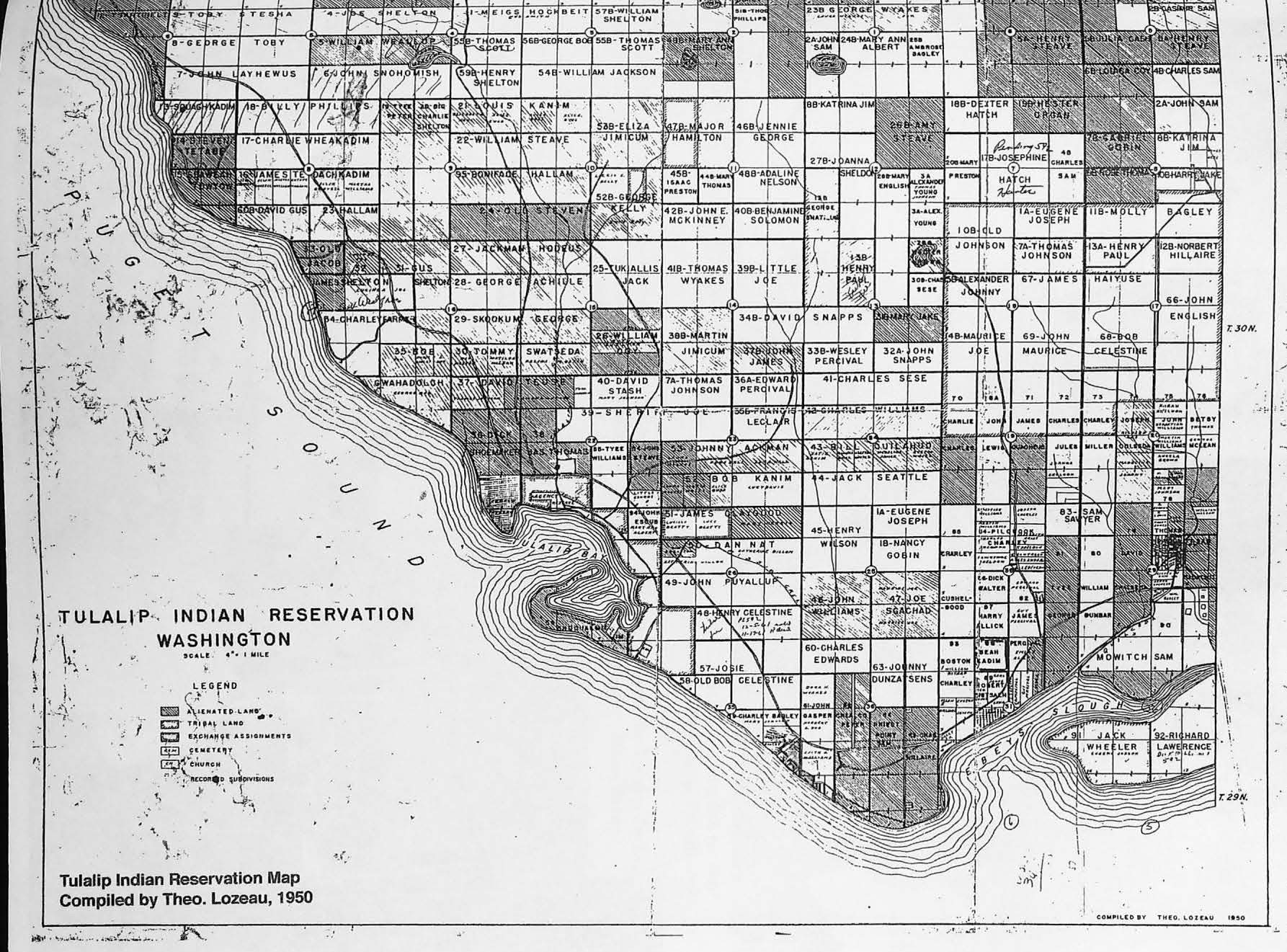

Additionally, in spite of the Treaty of Point Elliott’s apparent affirmation indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination on the reservation, they were often dispossessed of what little land had been guaranteed to them in the treaty. The Dawes Act of 1887 allowed the federal government to divide reservation land into allotments for individual tribal members. The Tulalip reservation was divided into 95 allotments, far fewer than the total number of indigenous families living there, leaving hundreds with no land of their own. To add insult to injury, in 1902, the Indian Agent forced all Tulalip people to move their allotments away from the bay, to parts of the reservation where there were few roads, houses, or waterways.[5]

Extreme poverty led many Tulalip to sell their land to non-indigenous people–today only about 60% of the reservation is owned by Tulalip tribal members.[6] Dover notes that not all land that passed out of indigenous hands was willingly given, as she recounts that a family friend once returned from living off the reservation to find that the Indian Agent had sold the forty-acre allotment of one of her family friends without his knowledge or consent.[7]

While white property developers had the opportunity to buy and sell reservation land, the Tulalip Board of Directors struggled to develop land for the tribe’s benefit or to receive revenue from developments on the reservation. In the 1940s, the board sought to develop the 300 acres of land at Mission Beach that had once been a residential school and lease it to generate some income for the tribe. They were told by an “area director” from Portland that the land “doesn’t belong to you…It isn’t yours. It never was and it never will be.”[8] This demonstrates the complete disregard that many government officials held for indigenous sovereignty and land rights. After some effort, the board finally received notice that the land that had been designated for them by treaty nearly a century prior was in fact theirs, and they surveyed the land into 50 lots.[9]

Map of the Tulalip Reservation in 1950. Dark parcels are labeled "alienated," meaning that they were owned by whites and outside tribal juridiction. (click for larger version)

Map of the Tulalip Reservation in 1950. Dark parcels are labeled "alienated," meaning that they were owned by whites and outside tribal juridiction. (click for larger version)

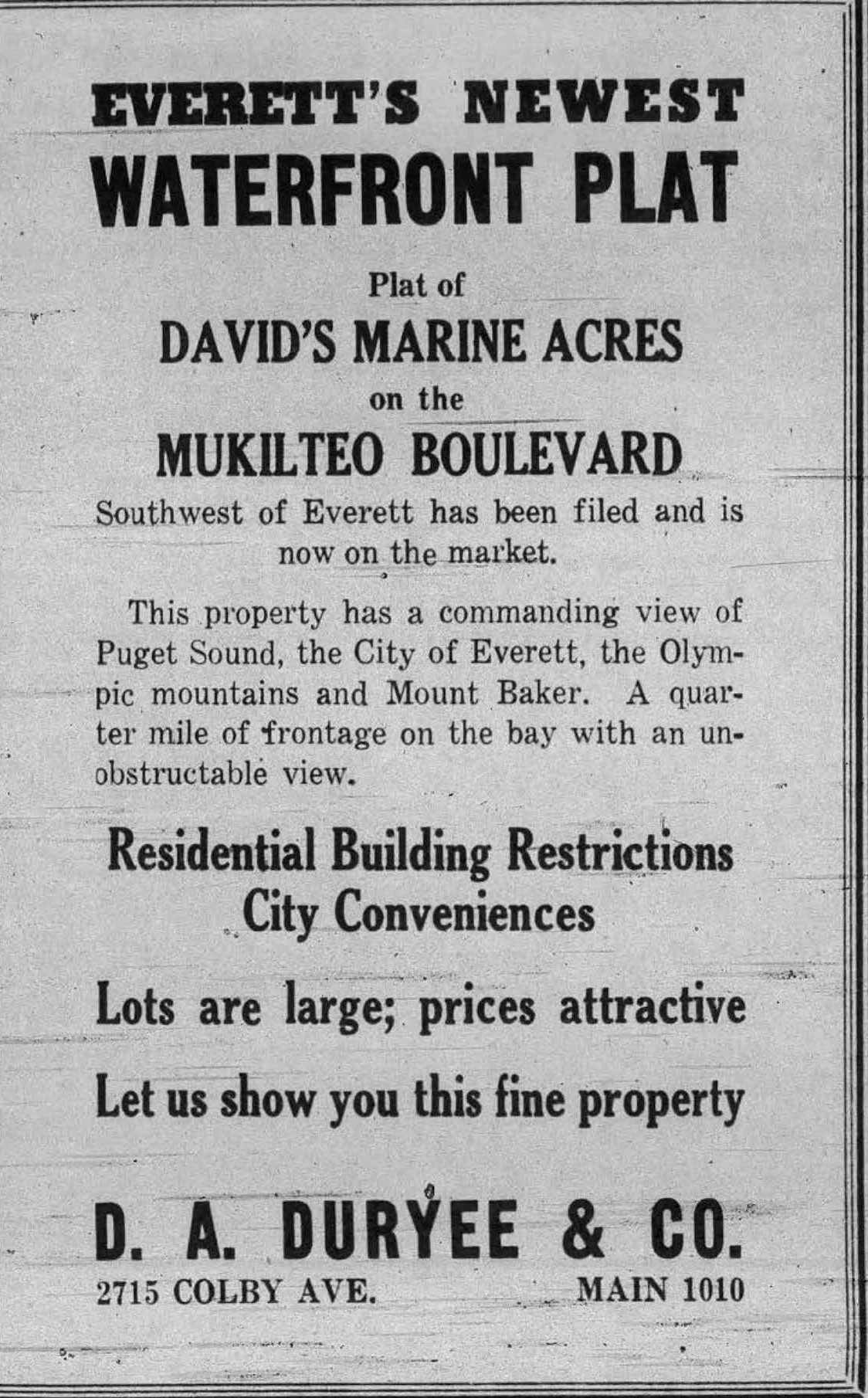

There was also the issue of the land at Priest Point which had been purchased by a real estate developer associated with Dan A. Duryee, whose companies developed several restricted subdivisions in the county. The developer purchased an allotment from a Tulalip man, but he also sold off the beach land that still belonged to the tribe. The Board of Directors believed they should receive some revenue from these sales, but they never did, as Dover states they did not pursue legal action against the developer given the large number of other issues they had to contend with.[10]

The Racial Restrictive Covenants Project has also found a racial restriction for a property in Charley Bagley’s Waterfront Tracts on the Tulalip reservation. In 1956, Delbert W. and Ione Morden sold their lot with the stipulation that “the deed given upon fulfillment of this contract shall contain restrictions against selling to anyone other than of the white race,” effectively excluding Tulalip people from being able to purchase a property on their own reservation.[11] Though this was only a single lot, rather than a full subdivision restriction, when taken with the other examples of native land dispossession here, it suggests the connectedness of the various ways in which white Americans in Snohomish County sought to exclude all but themselves from the economic benefits of land ownership.

Racial Exclusion and Attacks on Asian Workers

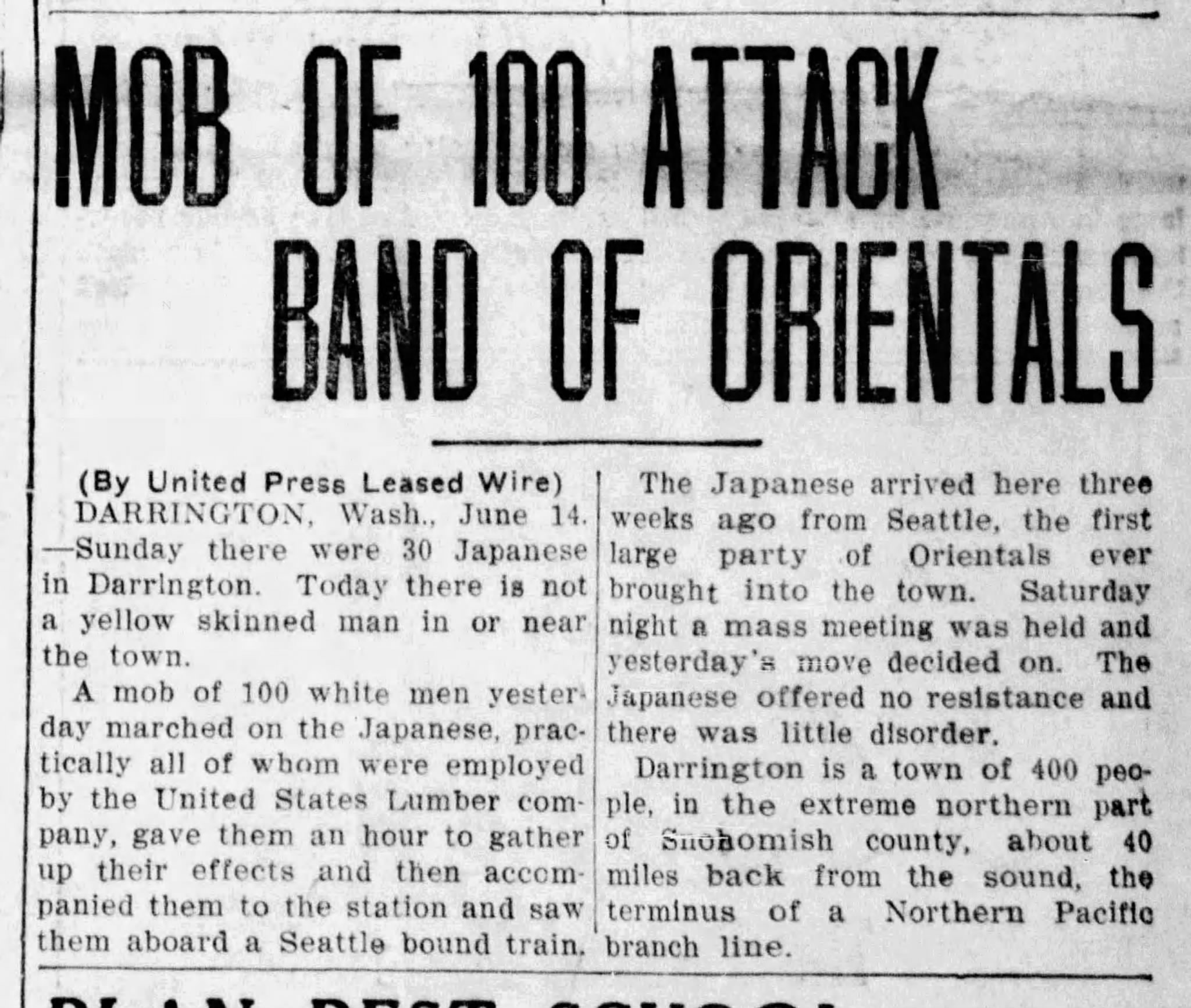

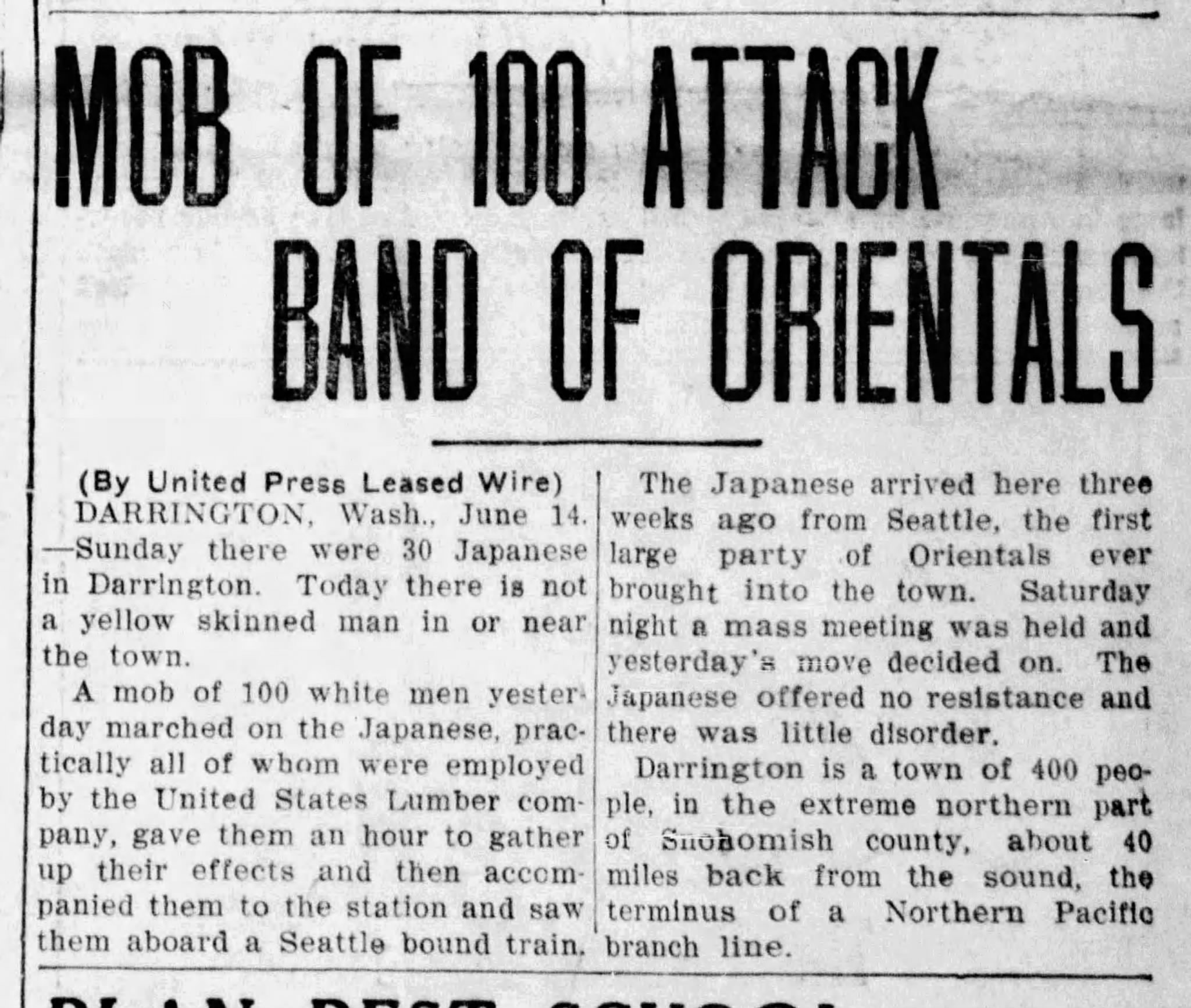

Spokane Press June 14, 1910

Spokane Press June 14, 1910

The early 20th Century in Snohomish County was marked by efforts to exclude ethnic minorities from making the county their home and to forcibly remove those who were already there. This primarily took the form of white resistance to Asian labor.

In 1907, following anti-Asian riots in Bellingham and Vancouver B.C. and against the backdrop of impending mill closures, white Everett residents violently drove South Asian workers out of the city. In September of that year, the Everett Trades Council presented a request to the mayor that all Asians and especially people from India be removed.[12] Animosity continued to build towards Indians, who the whites called "Hindus" but were mostly followers of the Sikh faith, until, on November 2nd, a mob of several hundred white workers gathered to destroy Indian workers’ housing. The stated purpose of the demonstration was to terrify the Indian workers and force them to flee the city.[13] Fearing for their lives, the Indian workers sought temporary refuge in city jail and then left the city two days later.

A letter to the editor of the Everett Daily Herald states that, “while everyone who believes in fair play condemns Saturday night's anti-Hindu demonstration, there cannot but be a feeling of general satisfaction over the departure of the Hindus from this city as a result.”[14] The actions of the mob and the coverage it received in the Herald indicate that public opinion was generally against the presence of Indian workers in the city, and this riot is a clear example of how racist sentiment manifested in violence that kept people of color out of the county.

With South Asians gone, Japanese people became the next target. In 1910, an anti-Japanese meeting was held in Everett in response to the increasing number of Japanese workers in neighboring Mukilteo. Attendees of the meeting created an “All-American League” and speakers proclaimed that “the United States must be maintained as a white man’s country at all hazards.”[15] That same year, a mob of 100 white men drove the 20-30 Japanese workers living in Darrington out of the small mill town by marching them to a train bound for Seattle. The Japanese workers had arrived only three weeks prior to work for the United States Lumber Company and had been the first people of Asian descent to live in Darrington.[16]

Efforts to exclude Japanese workers continued for the next two decades. In 1924, a committee of white residents of Lake Stevens appealed to the head of the Rucker Brothers Mill protesting its decision to hire a crew of Japanese laborers to reopen the mill after an eight month shutdown. W. J. Rucker, the head of the mill, claimed that the decision was made by a subcontractor, but there was still general public hysteria in the town that soon all 200 white mill workers would be replaced with Japanese workers.[17] When the Japanese crew arrived, whites forced them to quit and drove them away. News coverage of the protests referred to the hiring of Japanese workers as a “Japanese invasion” and a “yellow flood.”[19]

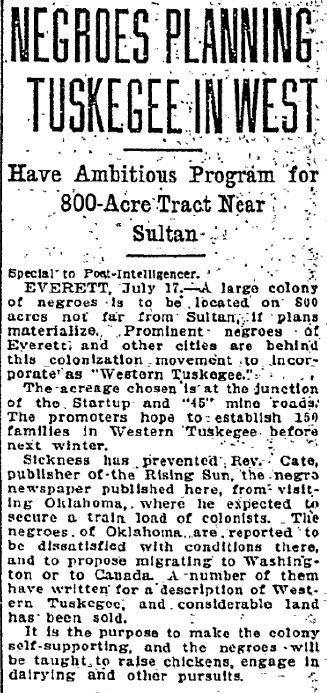

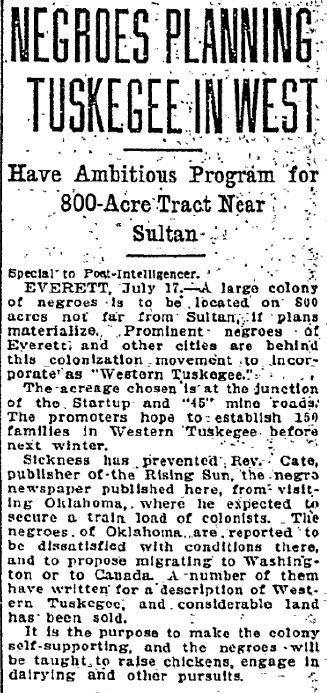

Seattle Post-Intelligencer July 18, 1911

Seattle Post-Intelligencer July 18, 1911

A small number of African Americans had settled in Everett early in the century and in 1911 news broke that a farm colony to be called “Western Tuskegee” was to be developed near Sultan, 25 miles east of Everett on the Skykomish River. The developers hoped to attract 150 Black families from Oklahoma and other states. The announcement was made by Rev. Thomas Cate, pastor of the Bailey Chapel A.M.E. church in Everett, but the company behind the plan was owned by two white men. The announcement received a quick response from white farmers in the area. Members of the Fern Bluff Grange passed a resolution condemning the settlement, issuing a bizarre statement that began with “while racial prejudice is wrong and should never be encouraged, there is, however, legitimate racial antipathy mutually existing between the white and negro races which is moral and salutary.” The resolution goes on to state that the grange is not trying to pass any judgement on the “moral or industrial qualities” of potential settlers, but that the presence of the two races together in the same area would be “detrimental to the community.”[20] The Tuskegee colony plan may or may not have had any chance of happening, but the reaction to it showed how difficult it was for African Americans to settle in the county.

The Mukilteo Japanese Community

In one part of Snohomish County, however, initial resistance to Japanese labor gave way for a time as a significant Japanese American community developed in Mukilteo. Japanese immigrants came to Mukilteo to work at the Crown Lumber Mill around the turn of the century, and by 1905 150 of the town’s 350 residents were Japanese.[21] At first, white workers reacted the way their counterparts did in other parts of the county. When the mill changed ownership in 1905, whites threatened to drive Japanese out of the mill but Japanese workers resisted, arming themselves with rifles in self-defense.[22] Two years later in 1907, the Everett Daily Herald reported on a “row” between white and Japanese workers in which a Japanese man was carried out on a plank, “badly whipped.”[23] In addition to being harassed and sometimes attacked by white workers, Japanese mill workers were also confined to segregated housing in a ravine near the mill that white residents called the “Jap Gulch” (now referred to as the Japanese Gulch). Megan Asaka notes that such dirty and rundown encampments as this “served not only to physically separate the Japanese workers from the white workers, but also to reinforce their status as disposable labor.”[24]

Students at Rose School in 1930 (photo: Mukilteo Historical Society)

Students at Rose School in 1930 (photo: Mukilteo Historical Society)

Gradually tensions eased and as Japanese wives and brides arrived after the 1908 "Gentlemen’s Agreement" restricted immigration of male laborers, the Japanese American community began to stabilize. Crown Lumber allowed married couples to move into company homes that had been abandoned by white workers. Additionally, while single men remained in segregated housing in the gulch, the presence of Japanese families in schools and churches increased acceptance amongst the white population.[25] Japanese and white children attended school together, as evidenced by Rosehill Elementary School photos from the 1920s, and one white resident held a class to teach a small group of single Japanese men English.[26]

However, despite this growing social acceptance, the economic status of Mukilteo’s Japanese community remained precarious compared to both American-born white residents and recent European immigrants. Washington’s alien land laws prevented Japanese immigrants, who were ineligible for citizenship, from being able to buy homes, forcing Japanese Mukilteo residents to live primarily in company housing or boarding houses.[27] When the Crown Lumber Mill closed in 1930, many Japanese residents were forced to move to find work and housing elsewhere, causing the community to shrink throughout the 1930s.[28] The internment order of 1942 dealt the final blow, as the federal government forcibly relocated and incarcerated any people of Japanese descent who remained.

This example demonstrates how a lack of access to homeownership opportunities, in this case due to state and national laws, created instability and impermanence for people of color even in the presence of some level of social acceptance. It is also worth noting that property developers began to file racially restrictive covenants in Mukilteo in the early 1940s and the subdivision of Hagen’s Waterfront Tracts, which was developed and fully restricted by Engward H. and Jeanett B. Hagen in 1941, is located by the Japanese gulch, where many Japanese residents still lived in the year before internment.

KKK Activity in Snohomish County

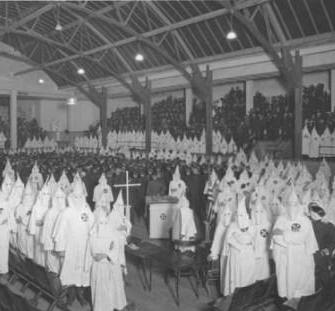

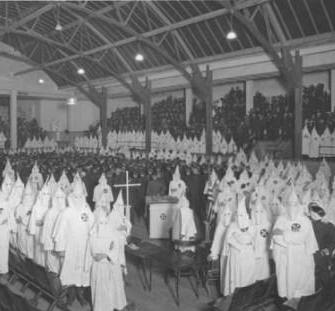

Klan mass initiation ceremony in downtown Seattle, 1923 (photo: Washington State Historical Society)

Klan mass initiation ceremony in downtown Seattle, 1923 (photo: Washington State Historical Society)

The Ku Klux Klan was reborn after World War I and became immensely popular and powerful, claiming four million members nationwide in the 1920s. In 1922, the Everett Daily Herald received an anonymous letter, signed “Kligrapp of the Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan,” denying that a “warning letter” which was sent to a Black person in Everett came from any of the Klan’s members.[29] The Herald noted that this letter confirmed the existence of a Klan chapter in the area. Less than a month later, men in Klan attire entered the First Baptist church during services and gave money, a letter, and an American flag to the reverend. The letter expressed support for Baptist and other protestant churches and condemned “immoral conditions” in the city and county. It went on to say that “we intend to make our city and county a better place to live. Our civil authorities must clean up these conditions or retire from office” and was signed by “Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.”[30] These relatively minor incidents foreshadowed a growing base of support for the KKK within the county.

On July 12, 1924, a large KKK initiation ceremony just East of Stanwood drew around 8,000 Klansmen and 2,000 spectators. “Several thousand” people were initiated into the Klan at the event and participants burned three large crosses.[31] Two years later, on June 26, 1926, hundreds of Klansmen marched through downtown Everett as thousands of onlookers watched. At the end of the march, the Klansmen burned a cross at the intersection of Hewitt and Colby Avenues in South Everett, near Port Garner.[32] That same day, the Klan hosted a picnic near Silver Lake, attended by members from Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia, at which an estimated 200 people were initiated into the Klan.[33] The Klan in Snohomish County and the rest of the Pacific Northwest villified Catholics and Jews as well as Blacks and Asians but their cross-burnings and mass rallies must have been especially terrifying to people of color.

Restrictor Spotlight:

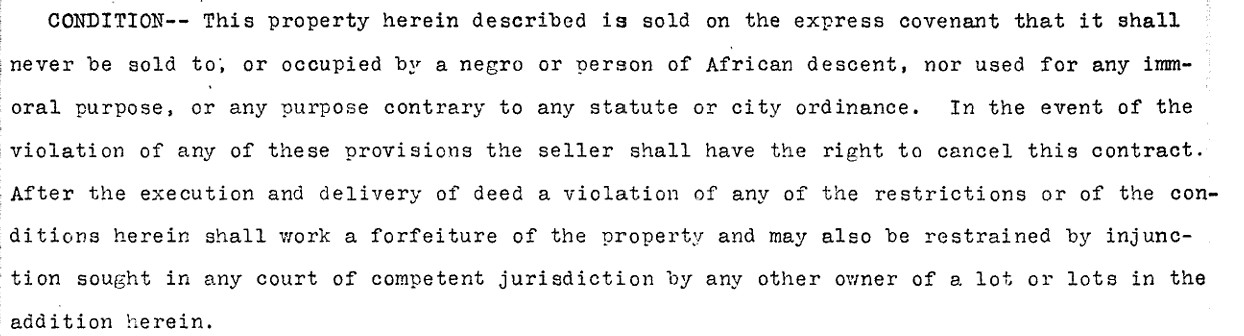

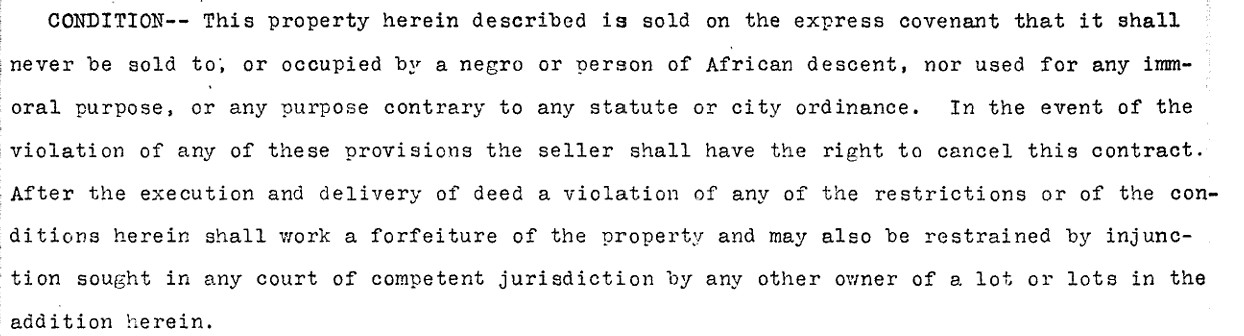

This restriction for properties in the Olympic View subdivision in Edmonds enumerates the penalties that homeowners would face if they violated the restriction. Click to read the 1925 deed of sale by Union Land Company.

This restriction for properties in the Olympic View subdivision in Edmonds enumerates the penalties that homeowners would face if they violated the restriction. Click to read the 1925 deed of sale by Union Land Company.

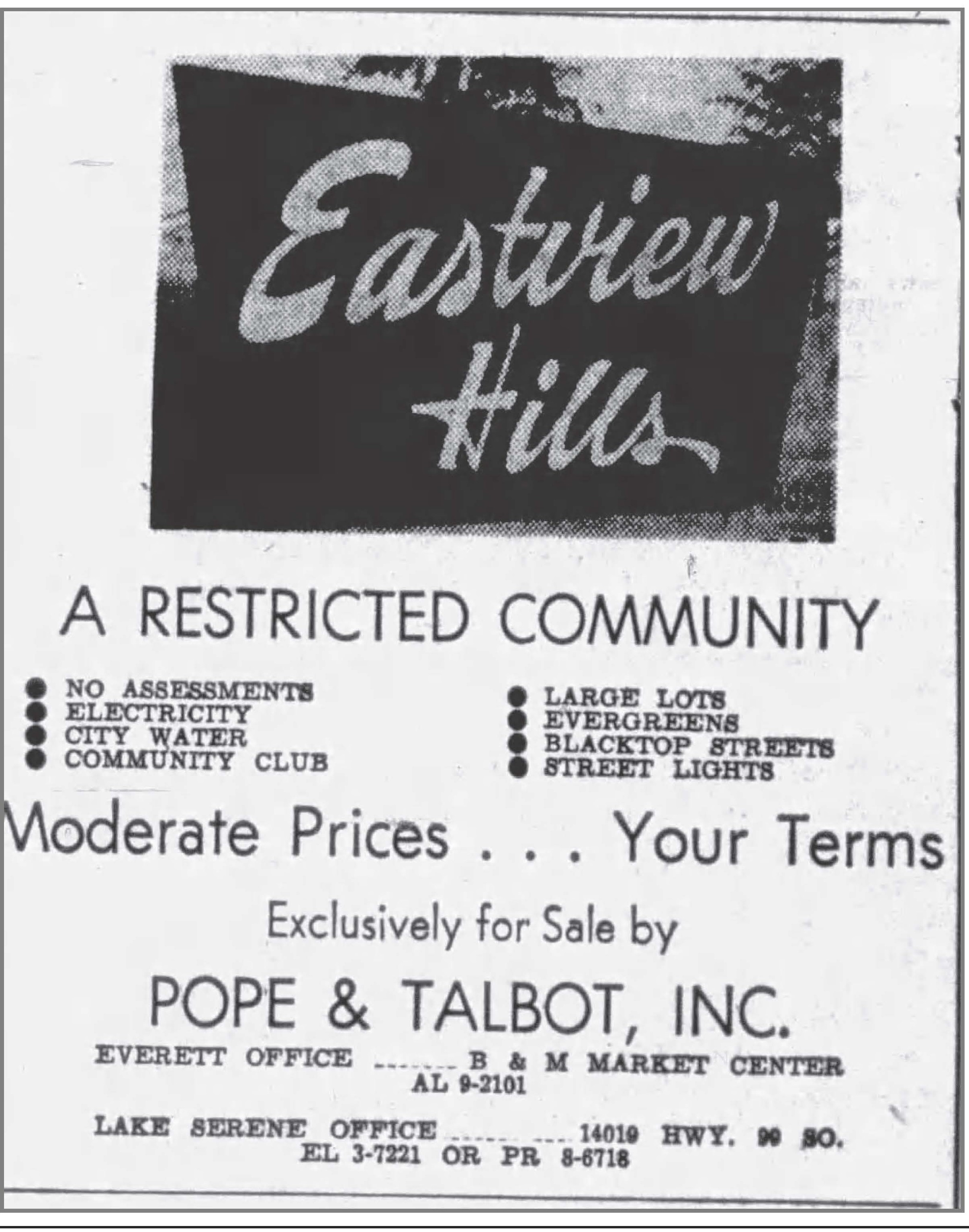

The developers and property owners who restricted thousands of parcels in Snohomish County to whites only also sought to keep people of color out of the county, and to limit the housing opportunities for those who did live there. Among the most prolific restrictors in the county were Pope & Talbot, the Everett Improvement Company, the Clifford Family, and C. D. Hillman. These companies and individuals played a significant role in shaping the development of Snohomish County.

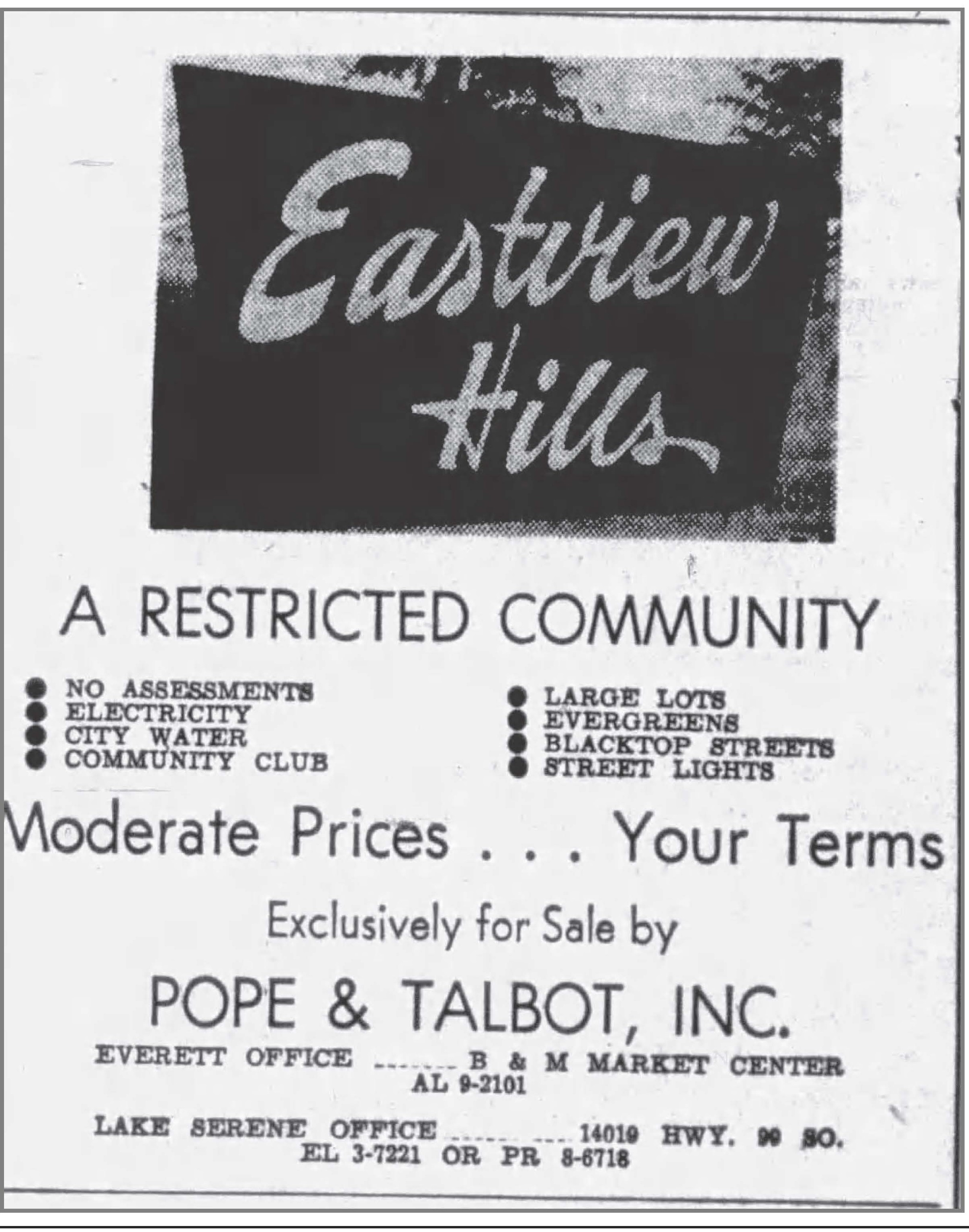

Pope and Talbot ad for Eastview Hills in southwest Everett, 1961

Pope and Talbot ad for Eastview Hills in southwest Everett, 1961

Pope & Talbot, known as the Puget Mill Company prior to the 1940s, was a lumber company founded in San Francisco in 1849. As in other parts of Western Washington, lumber companies were hugely influential in the development of Snohomish County with many of its towns and cities growing up around lumber and cedar shingle mills. Everett claimed to be the shingle capital of the world in the early 1900s. After logging an area, companies like Pope & Talbot then sold the land as residential property, often applying racial restrictions to their developments. Pope & Talbot restricted an estimated 766 parcels in Snohomish County, along with hundreds more in King County including the Broadmoor neighborhood of Seattle and in Lake Forest Park to the northeast of the city. Their Snohomish County subdivisions were located primarily in the suburban areas to the south of Everett, with the earliest being developed in 1927 and the latest being developed in 1949.

An unanswered mystery surrounding Pope & Talbot is why they applied racial restrictions to some properties and not others. The company was responsible for almost all of the early development of Alderwood Manor, an area that today includes Alderwood Mall, but only imposed racial restrictions in the deeds of sale for Alderwood Manor Division No. 22, one of the later subdivisions. A possible answer to this question is that Alderwood Manor No. 1-21 were developed from 1917-1928 before restrictive covenants became popular, while Alderwood Manor No. 22 was developed after World War II when the real estate industry vigorously advocated these instruments of exclusion. However, this cannot fully account for the discrepancy, as Pope & Talbot (then Puget Mill Company) began restricting other properties by deed in 1927 and presumably would still have been selling lots in the Alderwood Manor divisions developed in the 1920s at that time. Their pattern in Alderwood Manor stands in sharp contrast to their other Snohomish County developments, as they restricted all five of their Shelby subdivisions in Picnic Point, developed from 1927-1947 and all four of the Paine Field additions, developed in the late 1940s. In spite of this inconsistency, Pope & Talbot was the most prolific single restrictor in the county.

The Everett Improvement Company was incorporated in 1900 after Great Northern Railway executive James Hill acquired it from John D. Rockefeller and other investors who had hoped to make a fortune developing the port of Everett after the railroad pushed north from Seattle. At the time, the city was struggling to recover from the Panic of 1893 and many contemporaries credited the Everett Improvement Company and its first president, J. T. McChesney, with reviving the city.[34] In 1927, the Seattle Daily Times asserted that “This company built Everett as it is today. The company owned all the land in the beginning and sold the water and street car systems to the city.”[35] The company apparently saw no need for racial restrictions in its early years, but in 1940, with World War II raging and people moving to Puget Sound for defense jobs, the company began applying race exclusions to their new residential subdivisions, restricting a total of 713 properties to whites only.

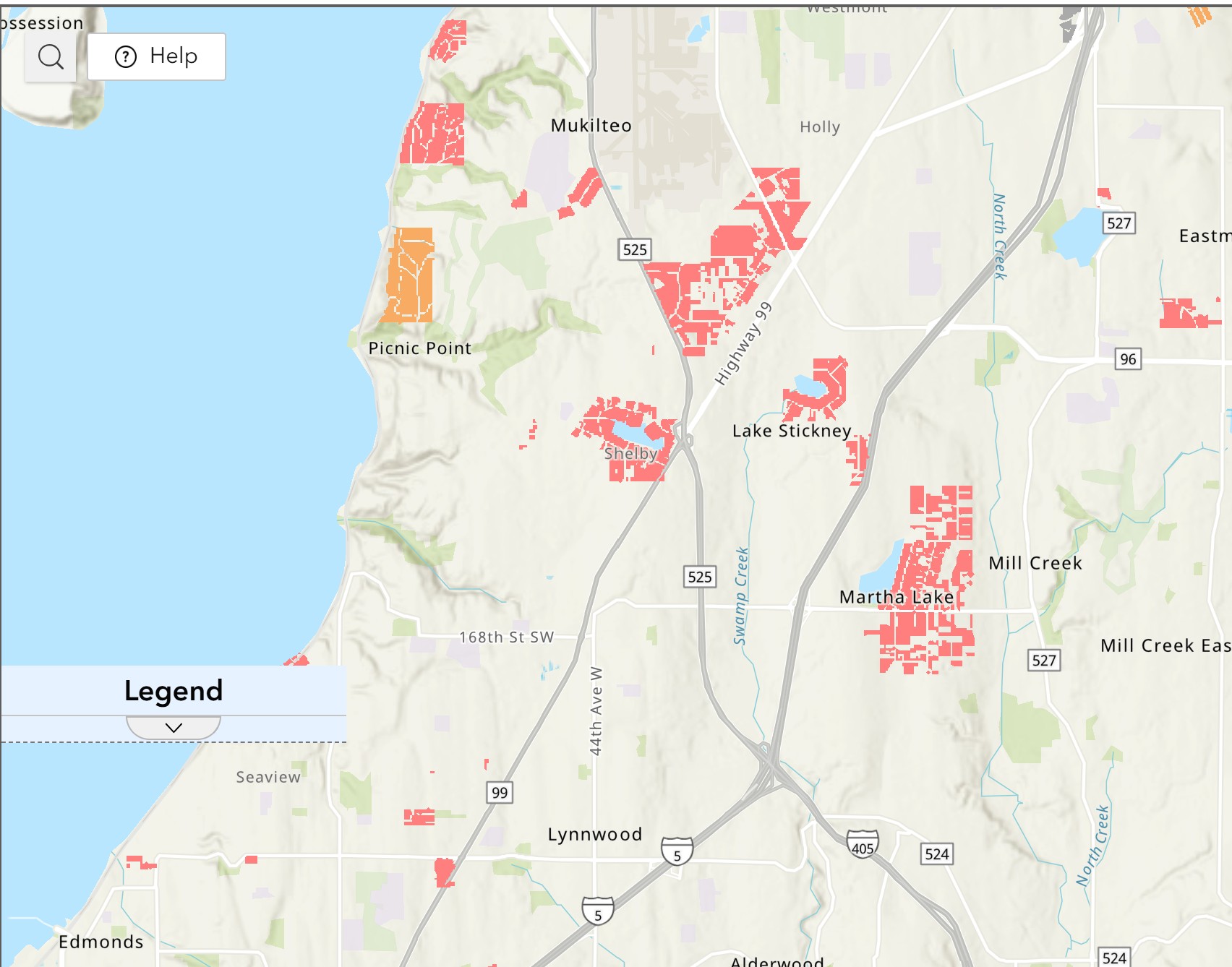

Subdivisions near Martha Lake and Lake Stickney were among the hundreds of parcels developed and restricted by Clifford family companies.

Subdivisions near Martha Lake and Lake Stickney were among the hundreds of parcels developed and restricted by Clifford family companies.

The Cliffords were a prominent family in the Puget Sound real estate industry, and both Edward Clifford and his sons, Edward A. Clifford and Richard Clifford, developed and restricted properties in Snohomish County. Edward Clifford Sr. was the secretary of the Clifford-Tulloch company, which restricted the Lake Roesiger Beach subdivisions in the late 1930s. Beyond Snohomish County, the company also purchased 143 restricted parcels on Whidbey Island from the Tyee Land Company in 1940, and Edward Sr. and his wife Myrtle restricted the Fair Oaks Beach subdivision outside of Olympia in the 1940s. Edward was extremely active in public life. He ran for governor of Washington as a Republican in 1924, and served on the Roosevelt Federal Savings and Loan Association from 1936-1944.[36]

His son, Edward A. Clifford, was an attorney and graduated from the University of Washington’s Law School in 1933.[37] Like his father, he had political ambitions–he ran for King County Assessor in 1938 and again in 1942, though he does not seem to have won either race. In Snohomish County, he and his wife Josephine restricted several Martha Lake subdivisions, the Shasta Park Tracts divisions, and Lake Stickney Tracts between 1946 and 1958. They also developed and restricted properties in Skagit, Mason, and King Counties, demonstrating the geographical reach of developers like Clifford, and thus the widespread impact of their decision to add racial restrictions to their properties.

His younger brother Richard and his wife Edith developed Shasta Park Tracts divisions one and two with Edward and Josephine in Brier in the 1940s. Richard and Edith also independently developed and restricted the Pleasant Beach subdivision on Lake Lawrence in Thurston County, outside of Yelm, in the 1940s. At the time of his death in 1987, Richard lived in the historically fully restricted subdivision of Sand Point Country Club in Seattle. Taken altogether, the Cliffords restricted nearly a thousand properties in Snohomish County, a county in which none of them ever appear to have lived.

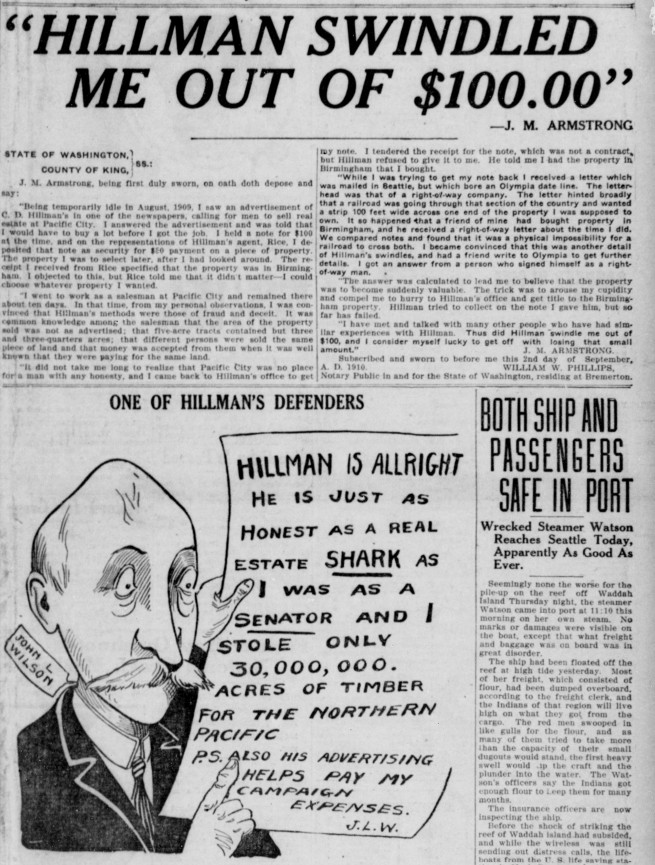

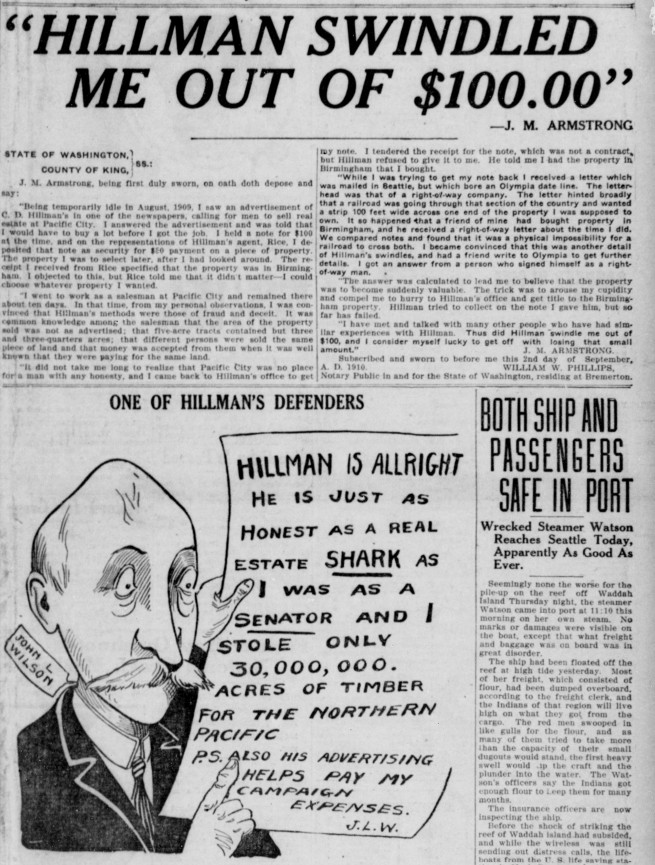

Seattle Star article describes C.D. Hillman's fraudulent schemes, September 3, 1910(click for enlarged view )

Seattle Star article describes C.D. Hillman's fraudulent schemes, September 3, 1910(click for enlarged view )

The final restrictor who warrants attention is Clarence Dayton “C. D.” Hillman. Hillman was born in rural Michigan and moved to California with his brother in 1891. He arrived in Seattle in 1897, where he began to buy properties in the city and its surrounding areas and sell them under misleading and often downright false pretenses to wild success, as he became a multi-millionaire within a few years of his arrival.[38] He was one of the first known restrictors in Western Washington, as he was filing deeds with racial restrictions in Pierce and King Counties as early as 1905. He began developing subdivisions in Snohomish County in 1904, and may have been applying restrictions to them as well, but because this project only has access to deed records for Snohomish County going back to 1919, this cannot be said for certain.

Hillman's developments in what is now Warm Beach, north of the Tulalip reservation, are of particular interest. Hillman bought large swaths of land in the area and developed them as C. D. Hillman’s Birmingham Water Front Addition, Divisions 1 and 2 in 1909 and 1910, respectively. Much of the land had been logged, so he planted Himalayan blackberries and elephant ear plants to hide the damaged landscape from view.[39] In 1909, he began to run advertisements in the Seattle newspapers promoting “grand free excursions” by boat from Seattle to the Birmingham developments.[40] At these excursions, Hillman presented Birmingham as a fully functional community with a nearby cannery and sawmill for employment, a town with shops and a community center, and orchards just beyond it to supply fresh fruit. In reality, the cannery and mill were equipped with machinery made up of random surplus parts, the stores were not operational and never would be, and the fruit Hillman said came from the orchards was actually purchased from Pike Place market in Seattle.[41] It is unclear exactly how many people bought land there as a result of this performance, as Hillman was known to exaggerate his sales, but suffice to say that many people were taken in by Hillman’s deception.

Those who bought land in Birmingham also faced problems with the properties themselves, as the lot lines were often incorrectly drawn and some found that their new lot had also been sold to other buyers.[42] These kinds of tricks were standard operating procedure for Hillman, but it was the Birmingham development which tipped the scale and caused his behavior to be exposed widely. The United States District Attorney, who had been aware of Hillman’s schemes for some time, was finally able to charge him with fraud in August 1910 when he used the mail to promote false claims about Birmingham.[43] In 1912, Hillman was found guilty of fraud and was sentenced to two and a half years in federal prison, in addition to a 20 day sentence in King County Jail for jury tampering. He served only 18 months of his sentence before it was commuted by President Taft. [44]After his release, Hillman moved to California, but continued to manage his Washington properties and develop new ones from afar under the banner of the Hillman Investment Company. For Hillman, the fallout of his fraudulent, erratic behavior lasted only a couple years, and he continued to have a profitable career in real estate for decades after his release.[45] Meanwhile, the racial restrictions Hillman imposed on his properties had devastating, far-reaching impacts on the lives of people of color in the state which still reverberate to this day.

Sundown Towns and Exclusion

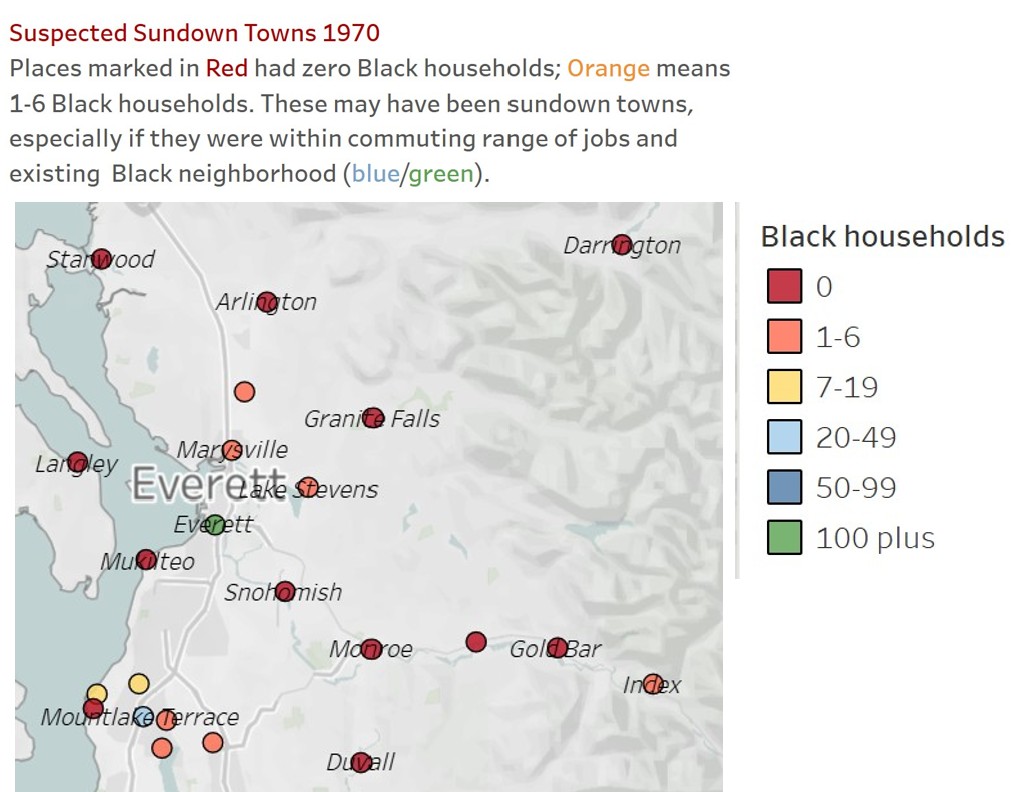

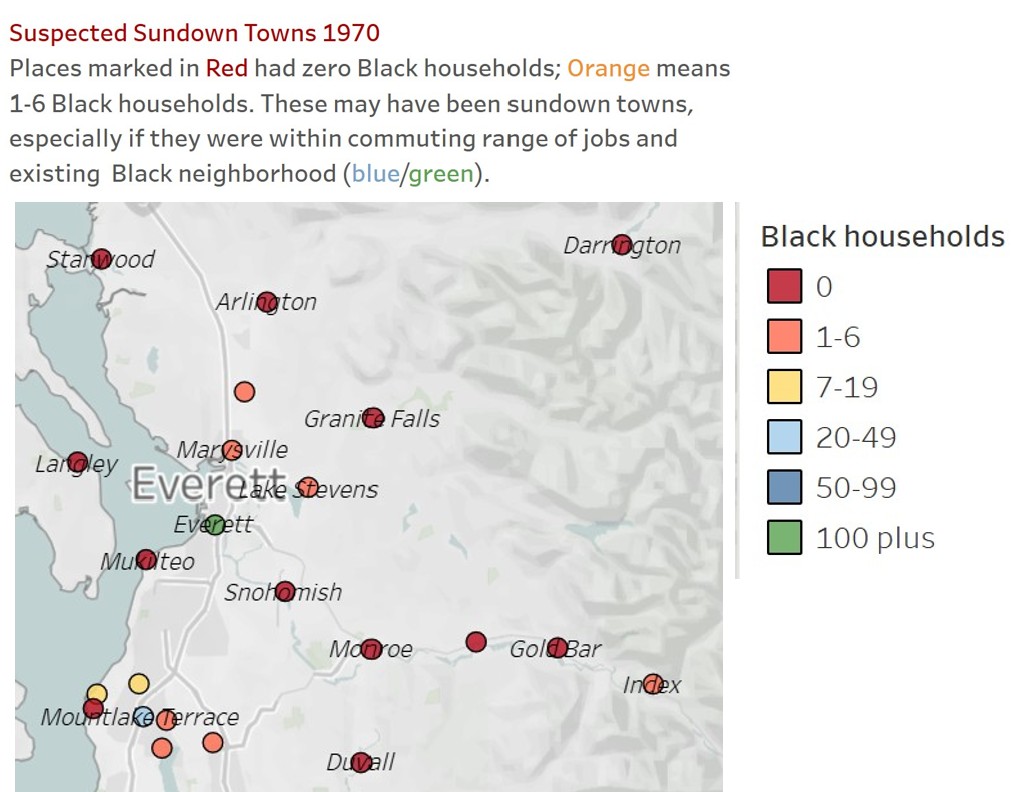

Click on map to see the number of Black households in Snohomish county census tracts in 1970. The tiny numbers suggest that outside of Everett African Americans faced intense housing discrimination and may have feared violence.

Click on map to see the number of Black households in Snohomish county census tracts in 1970. The tiny numbers suggest that outside of Everett African Americans faced intense housing discrimination and may have feared violence.

Racial restrictions in property records contributed to the efforts of white residents to exclude people of color from the county. At the 1960 census, there were nine cities or towns in the county with zero Black households: Edmonds, Mukilteo, Lynnwood, Intercity, Lake Stevens, Marysville, Monroe, Shoultes, Snohomish.[46] Given the close proximity of these south Snohomish County communities to Seattle, the absence of any Black households in these cities as late as 1960 is not mere coincidence, but rather evidence of an active campaign of exclusion.

In the 1970 census, two years after discrimination in housing was made illegal, not much had changed. Mukilteo still had zero Black households; Edmonds and Lynnwood claimed only nine and fourteen Black households respectively.[47] These patterns of exclusion cannot be tied solely to restrictive covenants. Exclusion was enforced by white realtors, white homeowners, and perhaps by law enforement practices with or without deed restrictions. These tiny population numbers may indicate that some of these communities had informal sundown rules, meaning that Black people were expected to leave the area before dark and would be harassed or assaulted by law enforcement and other white residents if they did not.

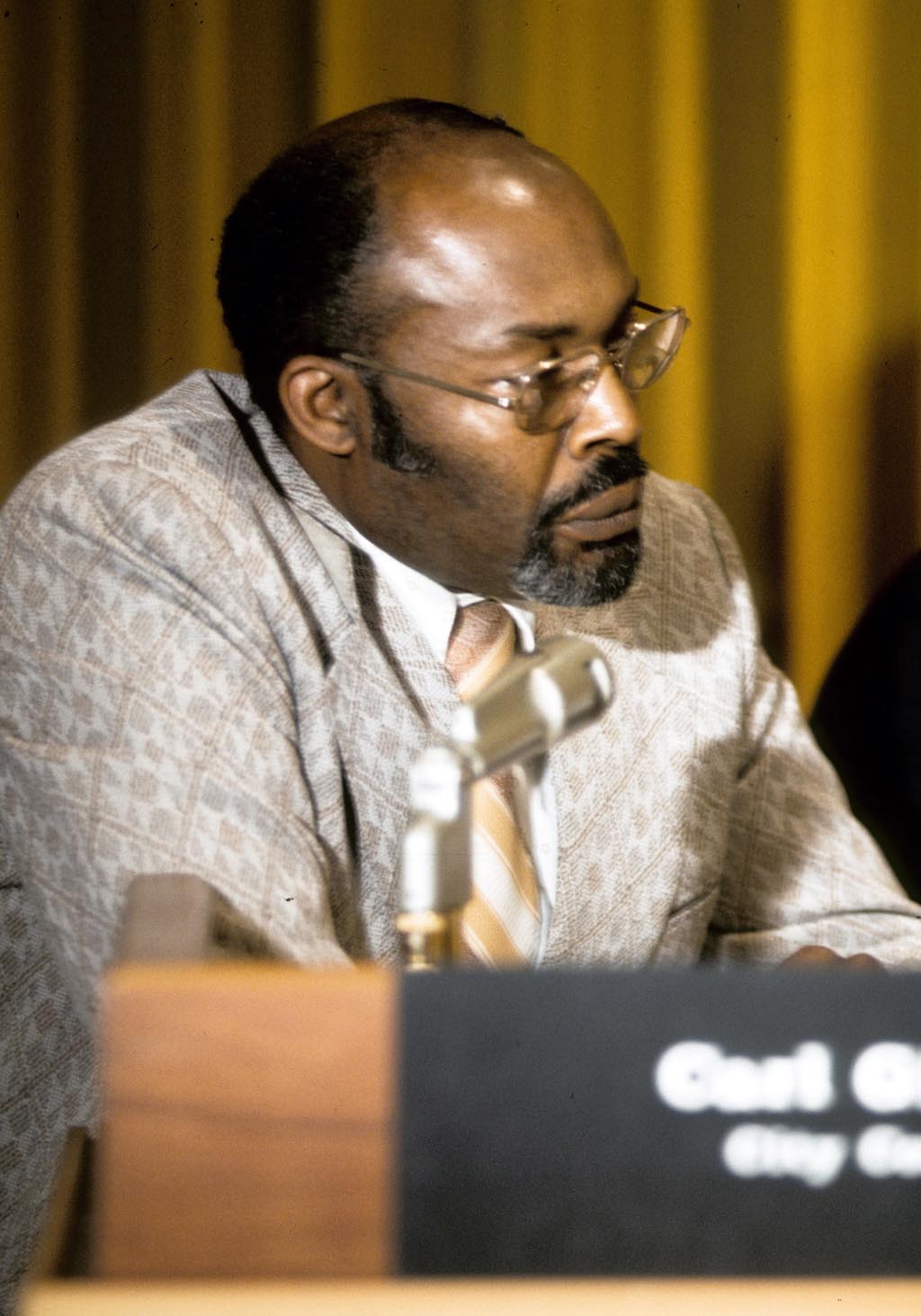

Everett, the county’s largest city, had the highest number of Black residents (380 in 1970), but still very few compared to nearby Seattle. Those who did live there often struggled to find a community within the city. From 1939-1952, there were only three entries for Everett in the Green Book, a publication which identified safe places for Black travelers to dine and sleep, and all were the homes of Black Everett residents: Jennie Samuels, George Samuels, and Jarrett T. Payne.[48] In 1957 and 1960-1962, there were no listings at all. When Clara Lumpkin, who would go on to be president of the Everett chapter of the NAACP, moved to Everett from Tucson, Arizona in 1968, she stated that she felt a “culture shock” and “so out of place” because of how few Black people were living there. In a 1990 Seattle Times article, she recalled that “we did everything in Seattle. We went to church there. We bought our groceries there…There wasn’t anything in Snohomish County for us.”[49] Carl Gipson, the city’s first Black city councilmember, expressed a similar sentiment, stating that “it was very tough” for Black families in Everett when he first lived there 1940s and 1950s because only mills or other blue-collar jobs would hire Black workers and there were too few Black people for them to start their own businesses to serve their communities.[50] These accounts demonstrate the harmful impact of the county’s exclusionary practices on those people of color who did live there.

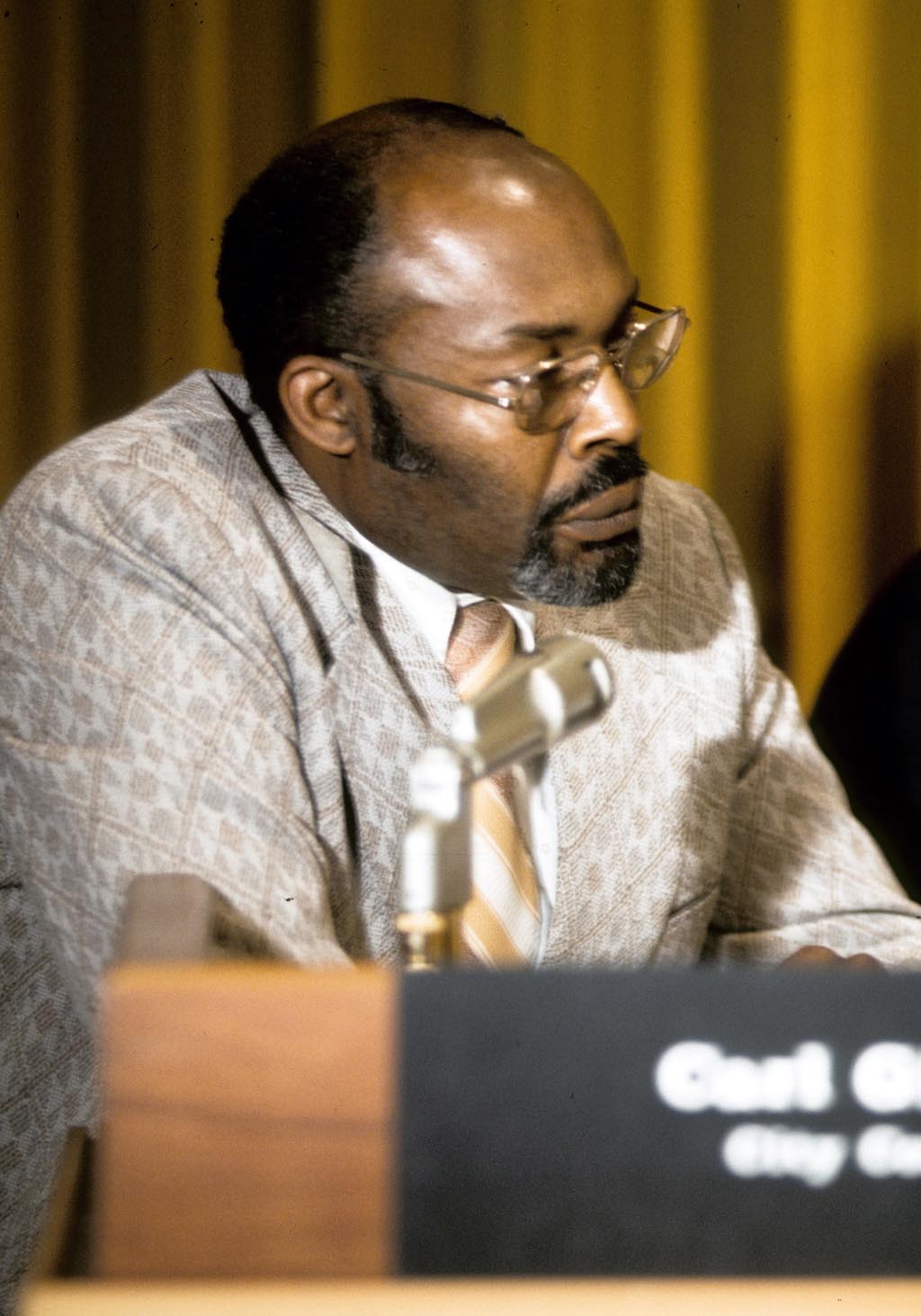

Carl Gipson’s Story: Social Enforcement of Residential Segregation

Carl Gipson serving on the Everett City Council 1974 (Courtesy Everett Public Library (3A182]/HIstoryLink))

Carl Gipson serving on the Everett City Council 1974 (Courtesy Everett Public Library (3A182]/HIstoryLink))

Carl Gipson was also the target of the racist harassment and intimidation tactics that white people often used to prevent people of color from moving into their neighborhoods. Gipson grew up in Jim Crow Arkansas and was deployed to first Bremerton and then Whidbey Island when he enlisted in the Navy during World War II. He and his wife lived in Everett while he was stationed on Whidbey Island because they could not find housing on the island, or in Mount Vernon or Anacortes, due to their race, despite the fact that Gipson was serving in the military.[51] After the war, he struggled to find work in Everett but was ultimately hired at the Sevenich Chevrolet Dealership, where he worked for about a decade. Reflecting in 1997 on the racism that was commonplace in the city at the time, he recalled that his Sevenich co-workers initially refused to work when he was promoted to foreman and that there were some bars in Everett that would break the glass after a Black person drank from it.[52]

Gipson also encountered obstacles when he sought to buy a house in the 1950s. Real estate agents would only show him and his wife properties in the south end of Everett near Paine Field, illustrating the power that real estate wielded in enforcing segregation.[53] However, Gipson had developed a personal relationship with an agent through his work, and in 1954 he took him to see a house on Hoyt Avenue at night so that the neighbors would not see them.[54] When the residents of this all-white North Everett neighborhood found out that the Gipsons had purchased the house, they threatened the man who had sold it to them and tried to block the sale. Fortunately, the banker who was handling the deal knew Gipson and his wife and told the neighbors that they could not stop them from borrowing the money.[55] Undeterred the neighbors next threatened violence against the Gipsons themselves. Gipson recalled that he told them, “no we’re going to move in. The only thing you tell anybody is if they come on my property they better have their hand out in front of them. I’m not going to have anybody harm my family.”[56] On the day the Gipsons moved in, their car was followed by a truck with two white men in the back brandishing shotguns. Determined to stay and resist, Gipson also carried a shotgun in his truck.[57]

Ultimately, some neighbors were welcoming towards the Gipsons, and the family was able to stay in the home. Nevertheless, this story demonstrates the role of the social enforcement of segregation in keeping certain neighborhoods all-white in the absence of restrictive covenants, as we have not found any formal racial restrictions around the home that the Gipsons purchased. Gipson was able to break through this barrier due to the relationships he had formed with influential people in the city through his work, but less well-connected families would likely not have even been permitted to tour the home the Gipsons purchased, much less buy and live in it. It is also worth noting that the media coverage of this incident is all retrospective, from interviews with Gipson that took place after his election to the city council. At the time the incident occurred, it was apparently not considered newsworthy by mainstream publications like the Herald. Thus, it is safe to assume that many other people of color in Everett and Snohomish County experienced similar racist harassment and violence, but never had the opportunity to share these experiences in the press. Carl Gipson’s story, then, should be taken not as a fluke or singular incident, but rather as an example that is emblematic of a broader pattern of social enforcement of segregation that occurred throughout the county.

Open Housing Laws and Desegregation

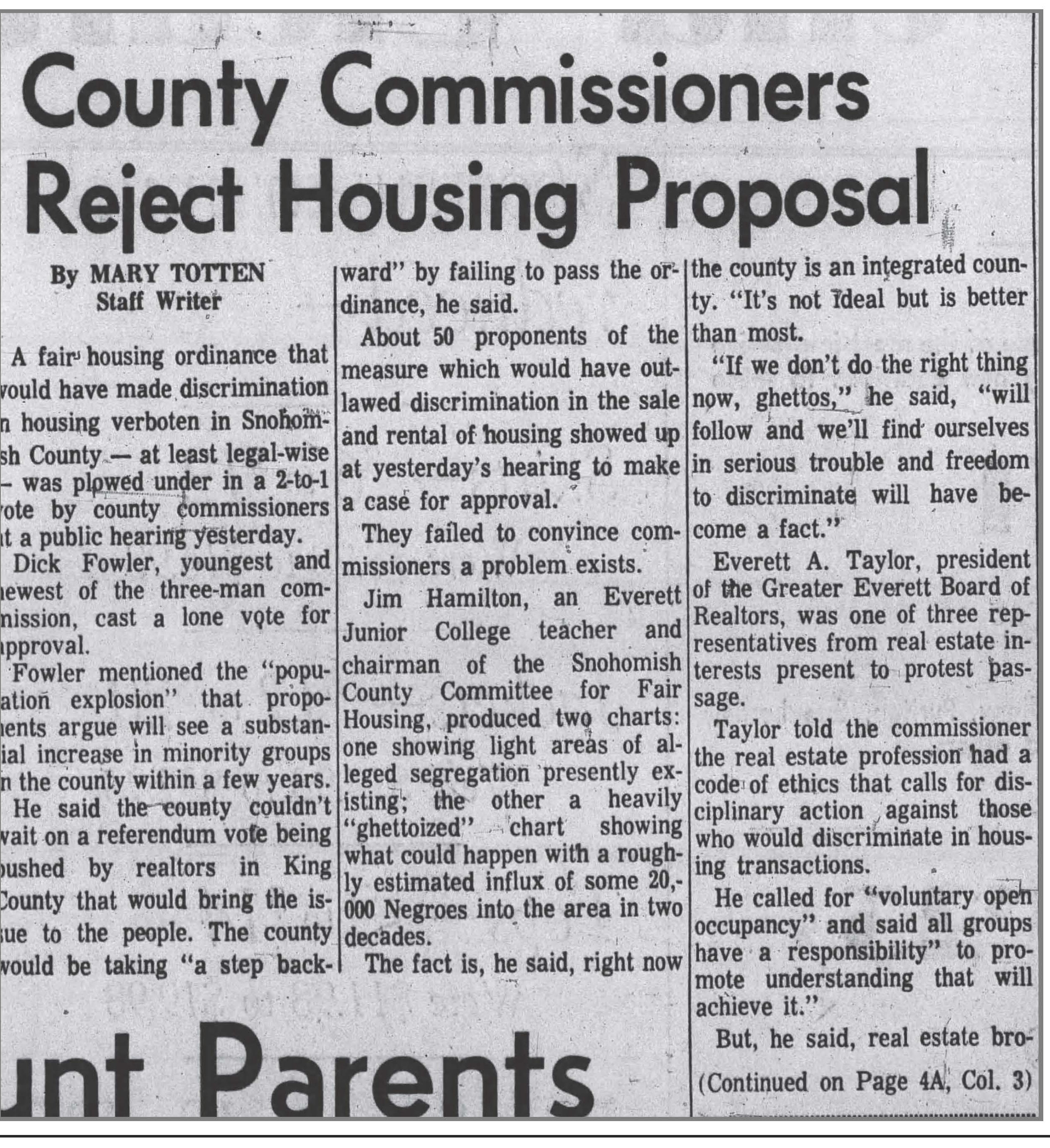

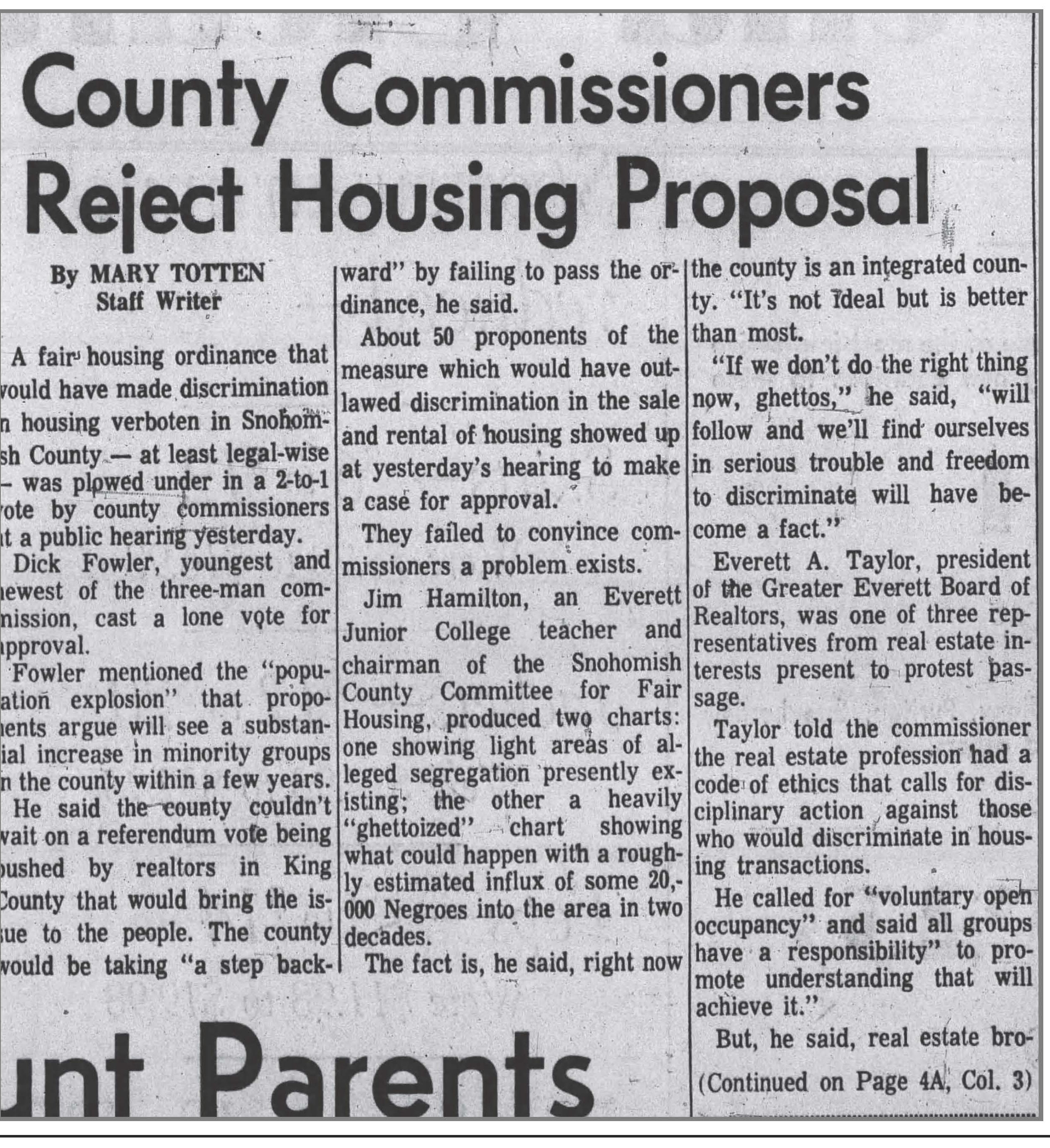

Everett Daily Herald, June 27, 1967)

Everett Daily Herald, June 27, 1967)

In the late 1960s, due to the efforts of civil rights activists both within the county and nationwide, attempts to pass fair housing ordinances began to take hold in Snohomish County. In June 1967, an open housing law that would have made housing discrimination in unincorporated parts of the county illegal was considered by the Snohomish County Board of Commissioners.[58] Jim Hamilton, the chairman of the Snohomish County Committee for Fair Housing, argued that in light of the expected diversification of the county in the coming decades, “if we don’t do the right thing now, ghettos will follow…and freedom to discriminate will have become a fact.”[59] Though it is fairly evident that the freedom to discriminate was already a fact in Snohomish County, Hamilton was likely right that segregation in the county could have become more severe without fair housing practices enshrined into law, as many people of color moved to the county in the 1960s to work at the Boeing plant. Countering that argument, the president of the Greater Everett Board of Realtors, Everett A. Taylor, spoke at the hearing to oppose the law. White supremacy prevailed in the subsequent election. The Commissioners rejected the open housing measure.

Some local drives for fair housing, however, were more successful. In April 1968, days after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, the South Snohomish County on Human Relations began a coordinated campaign to pass open housing laws in five suburban municipalities: Brier, Mountlake Terrace, Lynnwood, Edmond, and Woodway. A representative for the council acknowledged that there were very few Black people living in south Snohomish County but, echoing the failed countywide proposal, stated that “this area had better open its mind. Boeing is hiring blue-collar workers…and some of them will be Negroes.”[60] This effort began around the same time that the federal Fair Housing Act passed, but that law would not go into effect until the following year. Fair housing advocates pushed for local legislation that could be enacted immediately. On May 21, Everett City Commissioners unanimously adopted a fair housing law, the first in Snohomish County.[61] The Mountlake Terrace City Council followed soon after[63] and on June 19th, Edmonds became the third city in the county to ban discrimination in housing, and accompanied the law with the creation of a Fair Housing Practices Commission to mediate disputes over potential violations of the law.[64]

These successful campaigns for fair housing are indicative of shifting public opinion within the county regarding discriminatory housing practices. However, neither they nor the federal Fair Housing Act passed by Congress brought an end to racial discrimination or even to the recording on new racist property restrictions. The Racial Restrictive Covenants Project has located eight deeds from Snohomish County containing racially restrictive language that were drafted in 1968 or later. These include a deed from the developers of the Von Borstel Addition in Lake Stickney from September 1969, almost a year and a half after the passage of the FHA, and the re-sale of a property in Lake Roesiger Beach Subdivision two by Lillian Scheiderich in 1971. There is no indication anywhere on these deeds that these restrictions were by that time illegal and void, indicating that though laws may change, attitudes do not always follow.

Additionally, census data shows that though south Snohomish County has become increasingly diverse in the past five decades, as late as 2020 many areas in the North and East of the county remained nearly or entirely all-white.[65] Thus, the desegregation of Snohomish County remains unfinished, and requires continued, active effort to be fully realized.

Amanda Miller is Project Manager for the Racial Restrictive Covenants Project

Special thanks to Lisa Labovitch, librarian at Everett Public Library, for help with research and access to collections.

[2] Harriette Shelton Dover, Tulalip From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community (University of Washington Press, 2015), 45.

[3] Dover, Tulalip From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community, 230.

[4] Dover, Tulalip From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community, 232.

[5] Dover, Tulalip From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community, 71.

[7] Dover, Tulalip From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community, 177-78.

[8] Dover, Tulalip From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community, 220.

[9] Dover, Tulalip From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community. 220.

[10] Dover, Tulalip From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community, 220.

[11] Charley Bagley’s Water Front Tracts 599-331

[12] “Will Consider Hindu Question with Mayor,” Everett Daily Herald, September 21, 1907, 1.

[13] “Mob Scares Everett Hindus,” Everett Daily Herald, November 4, 1907, 1.

[14] [Anonymous letter], Everett Daily Herald, November 5, 1907, 5.

[15] “Anti-Japanese Mass-Meeting in Everett,” White Man, June 1910, 28.

[16] “Oust Japanese,” Snohomish County Tribune, June 14, 1910.

[17] “Lumber Town Wars on Japs,” The Seattle Star, January 12, 1924, 1.

[18] “Japs Barred, Mill is Idle,” The Seattle Star, January 28, 1924, 13.

[19] “Lumber Town Wars on Japs,” 1.

[20] “Negro Colony Is Not Desired by Grangers Who Go on Record,” Everett Morning Tribune, July 22, 1911, 6.

[23] “Japs are Said to be Arming,” Everett Daily Herald, September 13, 1907, 2.

[24] Megan Asaka, Seattle from the Margins: Exclusion, Erasure, and the Making of a Pacific Coast City (University of Washington Press, 2022), 184.

[25] Asaka, Seattle from the Margins: Exclusion, Erasure, and the Making of a Pacific Coast City, 206-7.

[26] Asaka, Seattle from the Margins: Exclusion, Erasure, and the Making of a Pacific Coast City, 207.

[27] Asaka, Seattle from the Margins: Exclusion, Erasure, and the Making of a Pacific Coast City, 208.

[29] “Ku Klux Klan is Formed in Everett,” Everett Daily Herald, February 14, 1922, 10.

[30] “Ku Klux Klan Garb Hides Identity of Visitors to Church,” Everett Daily Herald, March 10, 1922, 4.

[31] David A. Cameron, Snohomish County: An Illustrated History (Kelcema Books LLC, 2005), 197.

[32] “Klansmen March in Downtown Streets,” Everett Daily Herald, June 26, 1926, 17.

[33] “Klan Ceremonies are Held at Lake,” Everett Daily Herald, June 26, 1926, 12.

[34] “The Old-Timer Sez,” Everett Daily Herald, April 17, 1940, 11.

[35] “Pioneer Writes of Early Days in County,” Seattle Daily Times, January 23, 1927, 11.

[36] “Edw. Clifford, Veteran G. O. P. Figure, Dies,” Seattle Daily Times, May 2, 1954, 54.

[37] “Edward A. Clifford of Realty Firm Dies,” Seattle Daily Times, November 10, 1972, 51.

[38] Penny Hutchison Buse, Stuck in the Mud: The History of Warm Beach, Washington (Snohomish Publishing Company, 2011), 142.

[39],Buse, Stuck in the Mud: The History of Warm Beach, Washington, 120.

[40] “Big Land Sale,” Seattle Daily Times, October 2, 1909, 7.

[41] Buse, Stuck in the Mud: The History of Warm Beach, Washington, 128.

[42] Buse, Stuck in the Mud: The History of Warm Beach, Washington, 130.

[43] Buse, Stuck in the Mud: The History of Warm Beach, Washington, 135.

[44] Buse, Stuck in the Mud: The History of Warm Beach, Washington, 155 and 159.

[45] “Hillman, Hopeful, Talks of Plans for the Future,” Everett Daily Herald, February 19, 1913, 2.

[47] “Sundown Towns-Washington State.”

[48] EPL files: EPL-Black life, bios, Tuskegee

[49] Ignacio Lobos, “Snohomish Minorities See Clout,” Seattle Times, April 18, 1990, F1.

[51] KSER,“Carl Gipson, Everett Treasure,” 19:30.

[52] Bob Wodnick and Scott North, “Carl Gipson Felt the Sting, Persevered to Serve on Everett City Council,” The Daily Herald, October 19, 1997, 7A.

[53] KSER, “Carl Gipson, Everett Treasure,” 17:40.

[54] KSER,“Carl Gipson, Everett Treasure,” 18:35.

[55] Wodnick and North, “Carl Gipson Felt the Sting, Persevered to Serve on Everett City Council,” 7A.

[56] Wodnick and North, “Carl Gipson Felt the Sting, Persevered to Serve on Everett City Council,” 7A.

[57] Wodnick and North, “Carl Gipson Felt the Sting, Persevered to Serve on Everett City Council,” 1A.

[58] Mary Totten, “Open-Housing Law Rejected at Everett,” Everett Daily Herald, June 27, 1967, 1A.

[59] Totten, “Open-Housing Law Rejected at Everett,” 1A.

[60] Bob Lane, “Suburban Open Housing is Sought,” The Seattle Times, April 25, 1968, 19.

[61] “Everett Approves Open-Housing Law,” The Seattle Times, May 21, 1968, 6.

[62] “Open-Housing Law Sought in Terrace,” The Seattle Times, May 2, 1968, 21.

[63] “Edmonds Council Adopts Law Banning Housing Discrimination,” The Seattle Times, June 19, 1968, 9.

[64] “Edmonds Council Adopts Law Banning Housing Discrimination,” 9.

D.A. Duryee was a major developer who typical imposed racist restrictions(Baldwin Residence_Hall and Dykeman Collection, Everett Public Library)

D.A. Duryee was a major developer who typical imposed racist restrictions(Baldwin Residence_Hall and Dykeman Collection, Everett Public Library) Detail from 1876 map by Department of the Interior shows tribal reservations and original tribal territories. Notice the the area designated for the Tulalip reservation. Decades later whites would be allowed to buy reservation parcels and even impose racist restrictions.

Detail from 1876 map by Department of the Interior shows tribal reservations and original tribal territories. Notice the the area designated for the Tulalip reservation. Decades later whites would be allowed to buy reservation parcels and even impose racist restrictions. Harriet Shelton Dover (1904-1991) was the first woman elected to the Tulalip Tribal Council. Tulalip, From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community, was published after her death. In this photo (courtesy Tulalip Tribes & HistoryLink) she is wearing a cedar dress.

Harriet Shelton Dover (1904-1991) was the first woman elected to the Tulalip Tribal Council. Tulalip, From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community, was published after her death. In this photo (courtesy Tulalip Tribes & HistoryLink) she is wearing a cedar dress.

Spokane Press June 14, 1910

Spokane Press June 14, 1910  Seattle Post-Intelligencer July 18, 1911

Seattle Post-Intelligencer July 18, 1911  Students at Rose School in 1930 (photo: Mukilteo Historical Society)

Students at Rose School in 1930 (photo: Mukilteo Historical Society)  Klan mass initiation ceremony in downtown Seattle, 1923 (photo: Washington State Historical Society)

Klan mass initiation ceremony in downtown Seattle, 1923 (photo: Washington State Historical Society)

Pope and Talbot ad for Eastview Hills in southwest Everett, 1961

Pope and Talbot ad for Eastview Hills in southwest Everett, 1961

Carl Gipson serving on the Everett City Council 1974 (Courtesy Everett Public Library (3A182]/HIstoryLink))

Carl Gipson serving on the Everett City Council 1974 (Courtesy Everett Public Library (3A182]/HIstoryLink))  Everett Daily Herald, June 27, 1967)

Everett Daily Herald, June 27, 1967)