Olympia, the capital of Washington State, has a long history of racial discrimination, indeed racial exclusion. In 1970, the census for Olympia and Thurston County counted only 207 Black residents. Asians numbered only 620, while 582 Indigenous Americans remained on or near the county's two reservations. Overall, the county population was 98.2% White. These numbers speak to something other than racial segregation. Exclusion was the issue. And its history plays out today in homeownership rates, family wealth, and other effects of exclusion and inequality.[1]

Restrictive covenants were one of the reasons that across many generations people of color found it difficult to live in Thurston County, but the story of racial exclusion started much earlier.

Founded on exclusion

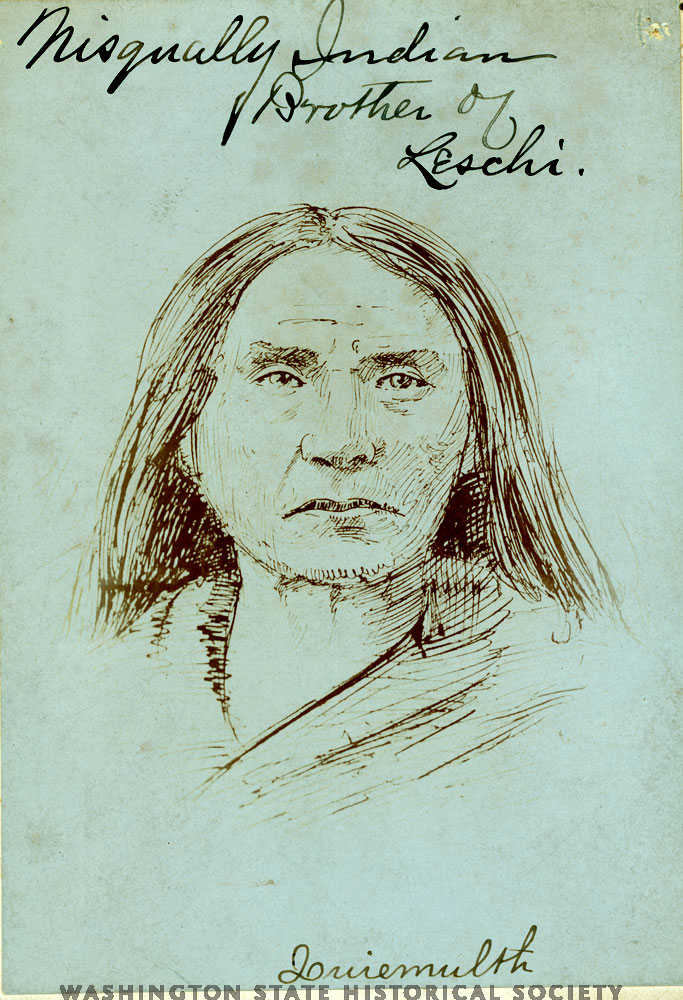

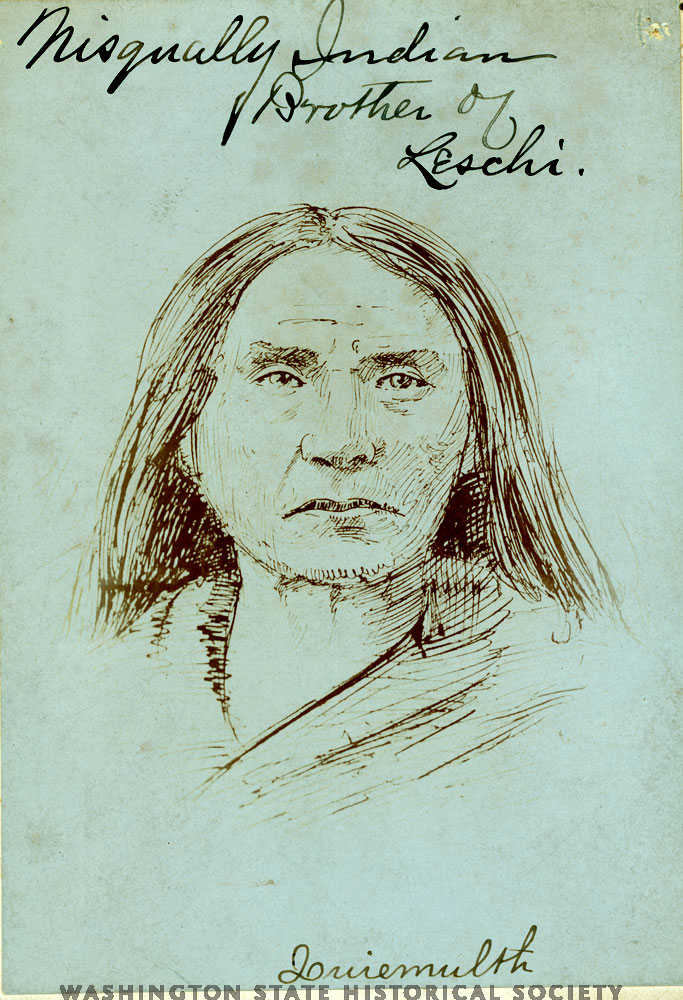

Chief Quiemuth of the Nisqually people was the elder brother of Chief Leschi. Despite surrendering to Gov Isaac Stevens, he was murdered while in custody. The artist and date of this sketch is unknown (courtesy: Washington State Historical Society)

Chief Quiemuth of the Nisqually people was the elder brother of Chief Leschi. Despite surrendering to Gov Isaac Stevens, he was murdered while in custody. The artist and date of this sketch is unknown (courtesy: Washington State Historical Society)

Nestled in the southernmost inlets of the diverse and abundant Salish Sea, what is now Thurston County has been home to Squaxin and Nisqually people for millennia. The Hudson Bay Company had established an outpost on Nisqually land in 1833 and in 1845, the Bush-Simmons party arrived at bəsčətxʷəd, a Squaxin village near what is now Tumwater Falls, establishing the first American settlement in what would become Washington state. George Bush and his family had walked all the way from Missouri, hoping to escape the laws that made life difficult for Black Americans. Oregon territory had offered more of the same, so along with the Simmons family and a few others, they had moved north from Fort Vancouver, settling among the Squaxin and Nisqually people.[1]

Others followed after the US claimed the region and established Washington Territory, an ominous development for the Indigenous nations. In 1854 Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens compelled the Squaxin, Nisqually, and other tribes to surrender nearly all of their lands at the Treaty of Medicine Creek, leaving each with small reservations. Nisqually chief Leschi was among those who vowed to resist the American invasion and theft of lands. In the 1855-1856 Puget Sound Wars, he was captured and later hanged. His brother, Chief Quiemuth, surrendered, only to be murdered while in custody. For all of the native peoples of the Puget Sound, the decades that followed became a test of survival as more and more Whites poured into the region. In 1930, only 191 Squaxin and Nisqually people remained, according to the US census.[2]

Keep Out

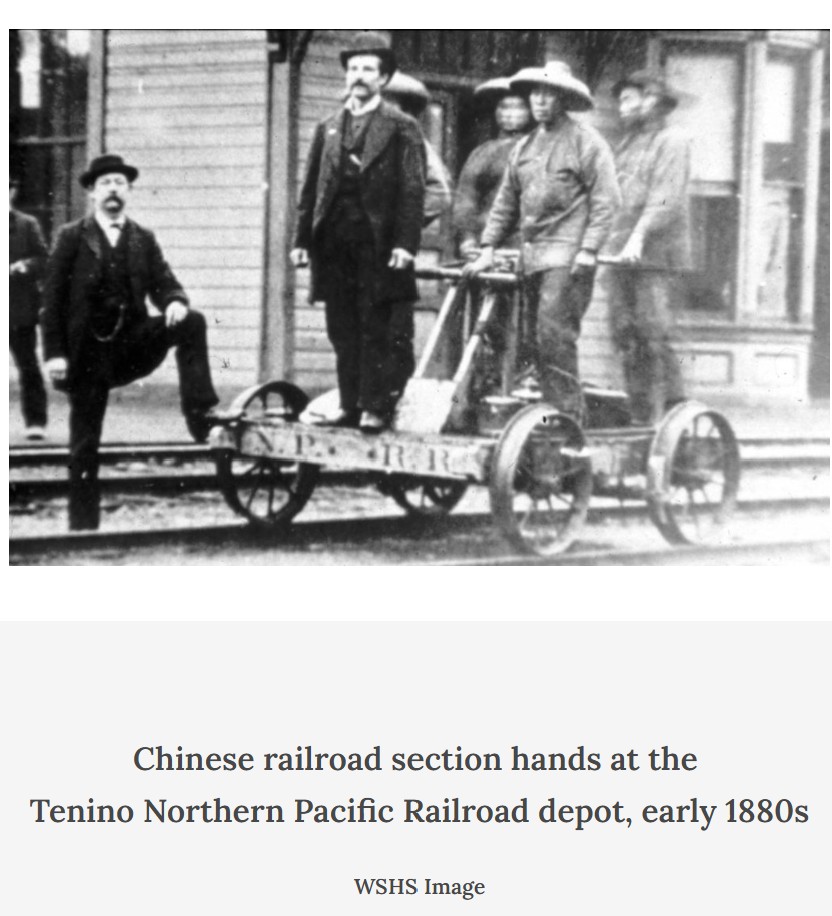

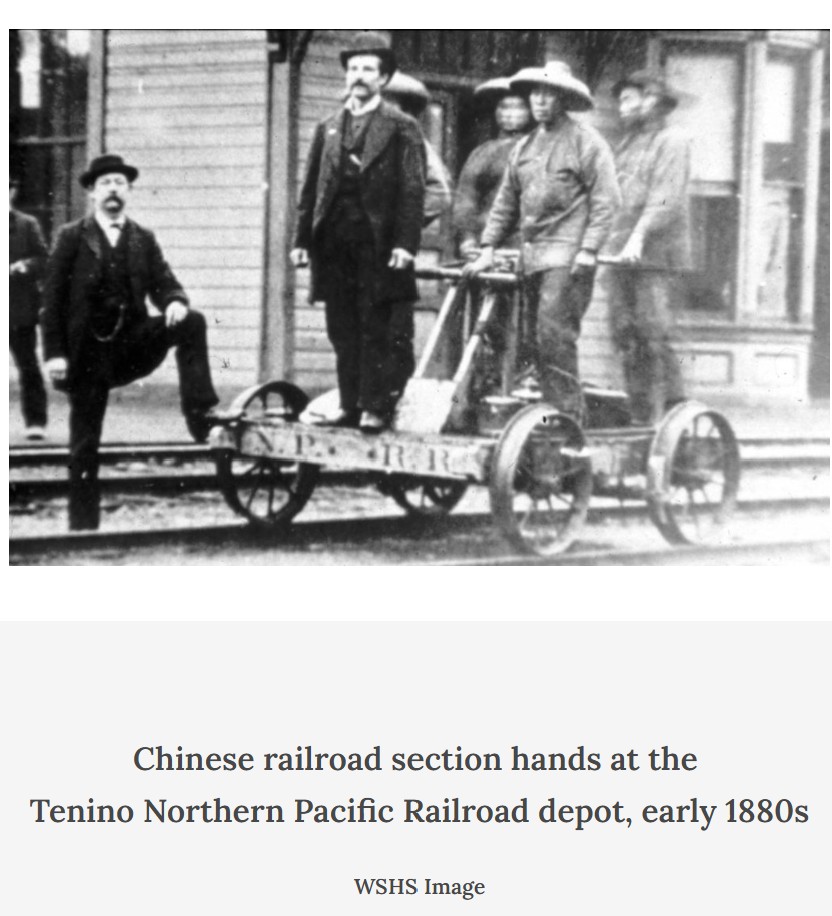

Courtesy Washington State Historical Society and Olympia Historical Society

Courtesy Washington State Historical Society and Olympia Historical Society

Despite the fact that George Bush and his family had found a home in what became Thurston County, later newcomers who were not White faced violence and exclusion. In small numbers, immigrants from China arrived in the county. Builders of railroad lines in 1870s employed Chinese workers who joined a few Chinese who had earlier found employment or established businesses in Olympia. A vicious anti-Chinese movement surged up and down the West Coast following the great Depression of the 1870s and the nationwide railroad strike of 1877. In 1882 Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, blocking future immigration from that country, but nativists were also determined to drive out Chinese people already in the US. White mobs, sometimes led by the Knights of Labor, attacked Chinese residents of mining towns, railroad and lumber camps, and then cities. In late 1885, the violence reached Tacoma, where a mob of White vigilantes, including the mayor, set fire to Chinese neighborhoods and drove out all Chinese residents. The "Tacoma method” was repeated in Seattle three months later, and the city was put under martial law.

Days after the Tacoma violence, White residents of Olympia held a town meeting resolving to expel Chinese people but in a “peaceable” way. The meeting resolved:

“while we fully realize the fact that we have too much of the Chinese element in our midst, we as clearly recognize the fact that they are here in and by the virtue of law and treaty stipulations, and that we are decidedly opposed to their expulsion by force or by intimidation, or by any other unlawful means, but we will at all times give our aid and support to any measures looking to a peaceable and lawful riddance of that element and a final solution of the ‘Chinese question’”[3]

Despite the resolution to expel Chinese residents without violence, on christmas eve a month after this meeting, a group of White vigilantes at the Thurston County railroad terminus in Tenino repeated the Tacoma method burning down the homes of local Chinese railroad workers. A few Chinese nevertheless managed to hang on in Olympia and others arrived in the following decades including Guey Gim Locke who worked as domestic servant near the Capital in the early 1900s. A century later, in 1996, Locke’s grandson Gary Locke was elected governor and moved into the governor’s mansion, less than a mile from where his grandfather had worked.

Economy, growth, and demography 1900-1940

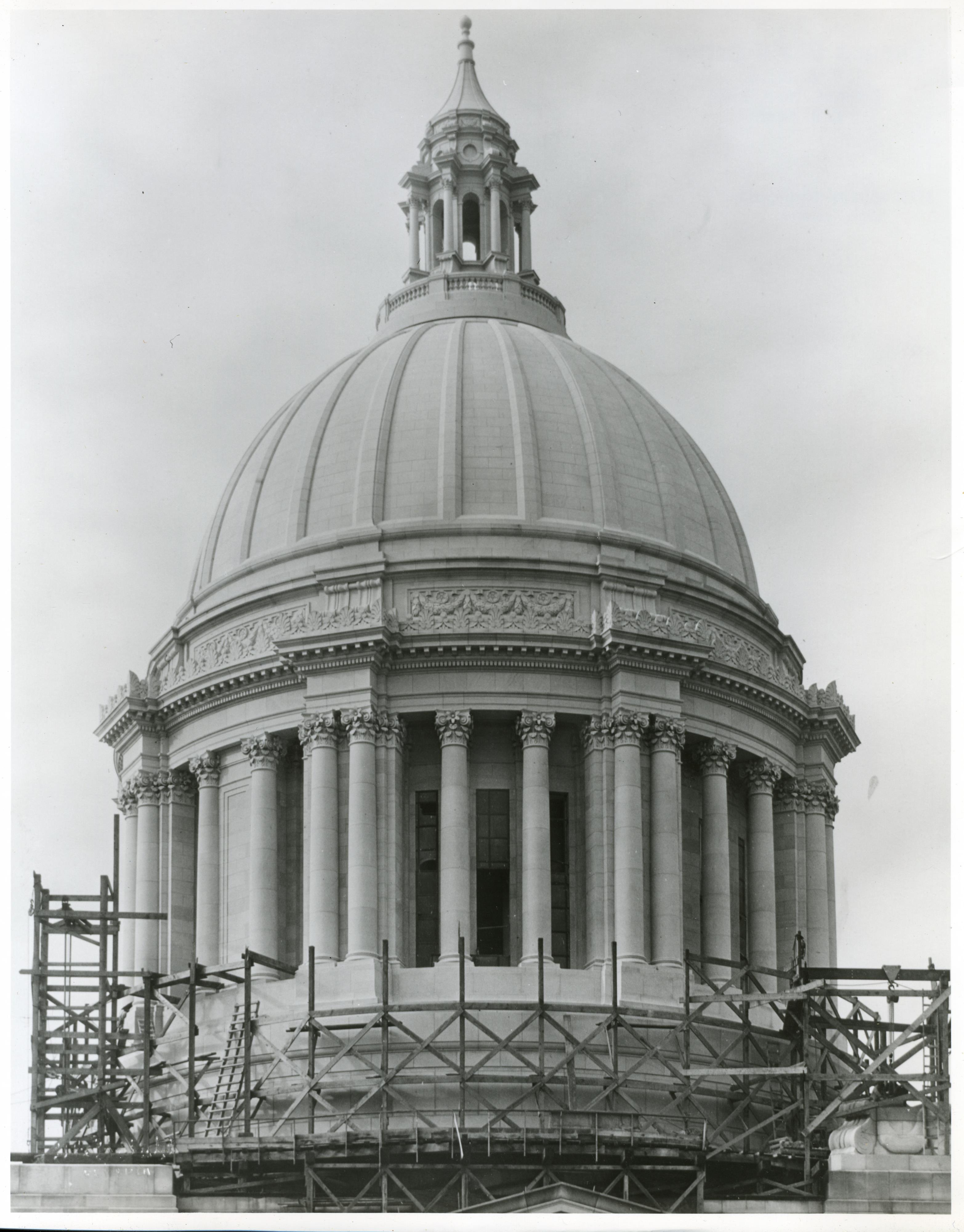

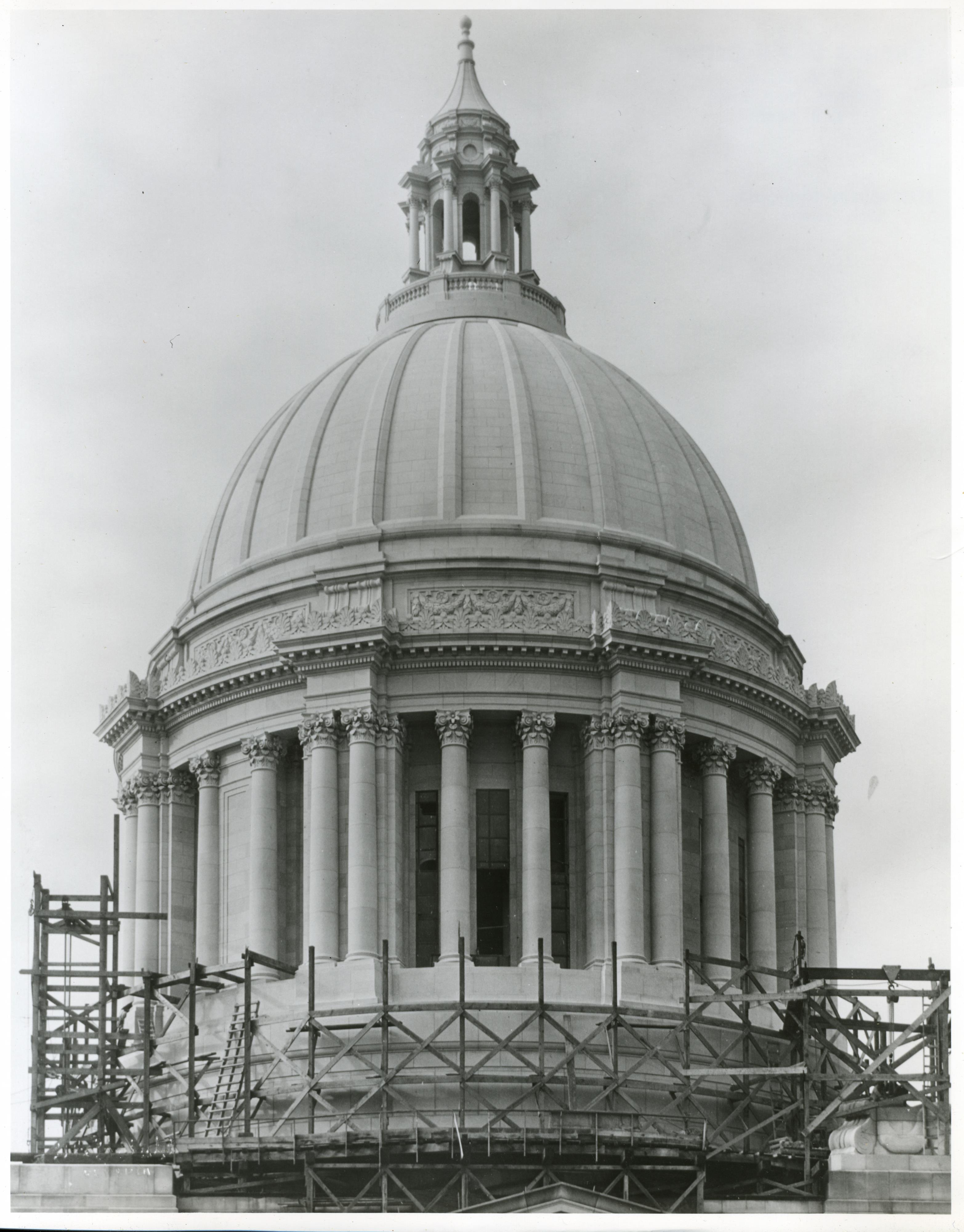

The new Capital buildings and campus were under construction starting in 1922. Fred Corlyon and Kate Stevens Bates were among the developers taking advantage of the redesigned Capital to open new subdivisions in what had been farm land southeast of the Capital grounds. (courtesy: Washington State Archives)

The new Capital buildings and campus were under construction starting in 1922. Fred Corlyon and Kate Stevens Bates were among the developers taking advantage of the redesigned Capital to open new subdivisions in what had been farm land southeast of the Capital grounds. (courtesy: Washington State Archives)

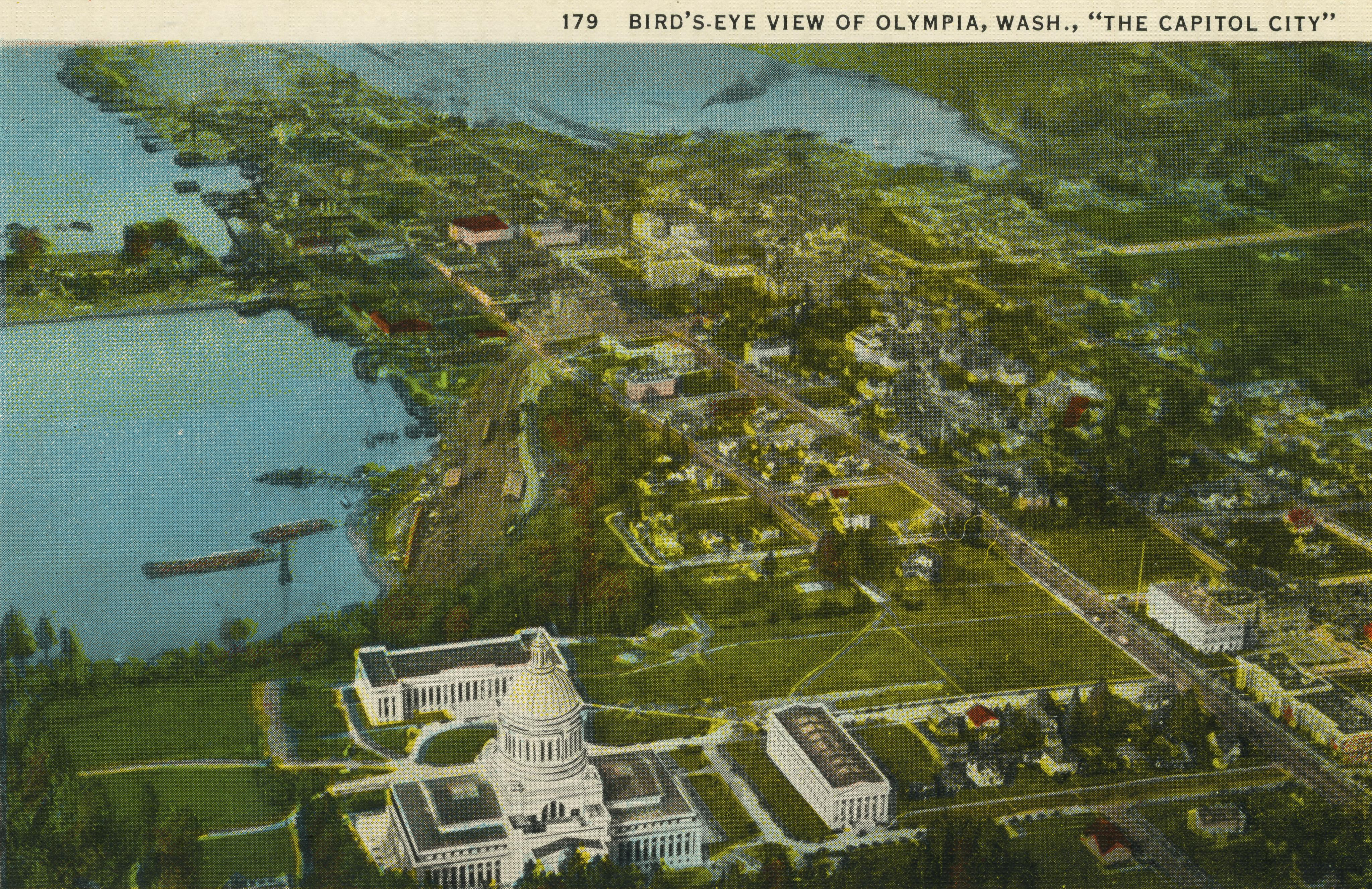

Proclaimed the capital of Washington, by Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens in 1853, Olympia has always enjoyed a unique economic and political position, as businesses, banks, and federal services were established near the seat of governmental authority. Nevertheless, it remained more a village than a city for many decades, claiming in 1900 fewer than 4,000 residents, amidst a county population of 9,937 (all but 220 of whom were White).[4]

But the 20th century would transform Olympia and Thurston County. A railroad connection had been established in 1878 and service expanded in the 1890s. Timber companies, along with steamship and ferry companies had built piers along the waterfront, and in 1920s the county committed to a major expansion, creating the Port of Olympia. Fort Lewis Army Base opened 20 miles north of Olympia in 1917, and following the First World War Thurston County became home to a growing number of young families seeking relatively inexpensive property outside of larger cities like Seattle and Tacoma. Major infrastructure projects in Olympia during the 1920s, including construction of the 4th Avenue Bridge connecting East and West Olympia (now Olympia-Yashiro Friendship Bridge), and a new state Capitol building reinforced the growing economic and political position of the city and further enticed prospective new residents.

The population doubled by 1920 and doubled again by 1940, reaching 37,285 in the county that year. Nearly all of these newcomers, however, were White. 1940 found only 33 African Americans and 315 persons of “other races” according to the census. That category would have included Chinese and Japanese Americans as well Nisqually and Squaxin tribal members.

In the previous century, methods of racial exclusion often rested on mob action and violence. Now a new method partially replaced violence as the 20th century progressed: restricting access to property and housing, thus making it hard for persons of color to contemplate settling in the county.

Legal changes of two kinds were involved. In 1920 and again in 1924, the Washington State legislature passed Alien Land laws making it illegal for persons not eligible for citizenship to own property, a law specifically aimed at Asian immigrants who under US Naturalization law could not apply for citizenship. The state Alien Land law destroyed the farming opportunities of Japanese families who since the turn of the century had specialized in growing berries and vegetables. Statewide the number of Japanese-owned farms declined by 65% during the 1920s, although some managed to continue by leasing land from White owners. No count is available for Thurston County, and it is not clear to what extent this law was enforced against Chinese immigrants.

Restrictive Covenants

Click map image to see interactive map of 1700 restricted properties

Click map image to see interactive map of 1700 restricted properties

All persons designated as not White faced the other instrument of exclusion. Finding housing in Olympia and other nearby towns was made nearly impossible for prospective renters or buyers who were not White by new practices implemented by local real estate brokers and land developers and enforced in state courts after the US Supreme Court ruled in 1926 that racial restrictive covenants were lawful and binding.

The term restrictive covenant covers a variety of property documents, including deeds and declarations of restrictions that are registered with county auditors by property owners and become permanently binding on all future owners. Restrictions based on race were introduced in cities and towns across the country after World War I as the Great Migration of African Americans began to change the demography of states outside the South and cities in the South.

Leading the campaign for racial restrictive covenants was the American Board of Realtors which urged affiliates across the country, including the Boards of Realtors in Seattle, Tacoma, and Olympia, to promote the instruments as a marketing tool and a way to protect property values. Racially restrictive housing covenants became a popular tool of exclusion in Pierce and King Counties to the north, and in Longview to the south in the 1920s but developers in Thurston were slower to adopt the practice. We have found documents restricting more than 1,700 properties in Olympia and Thurston county, some from the 1920s but most registered in the 1940s. The pace may indicate that real estate developers did not see much chance that Black or Asian people would contemplate moving to a county that had been so effectively restricted by other means until World War II.

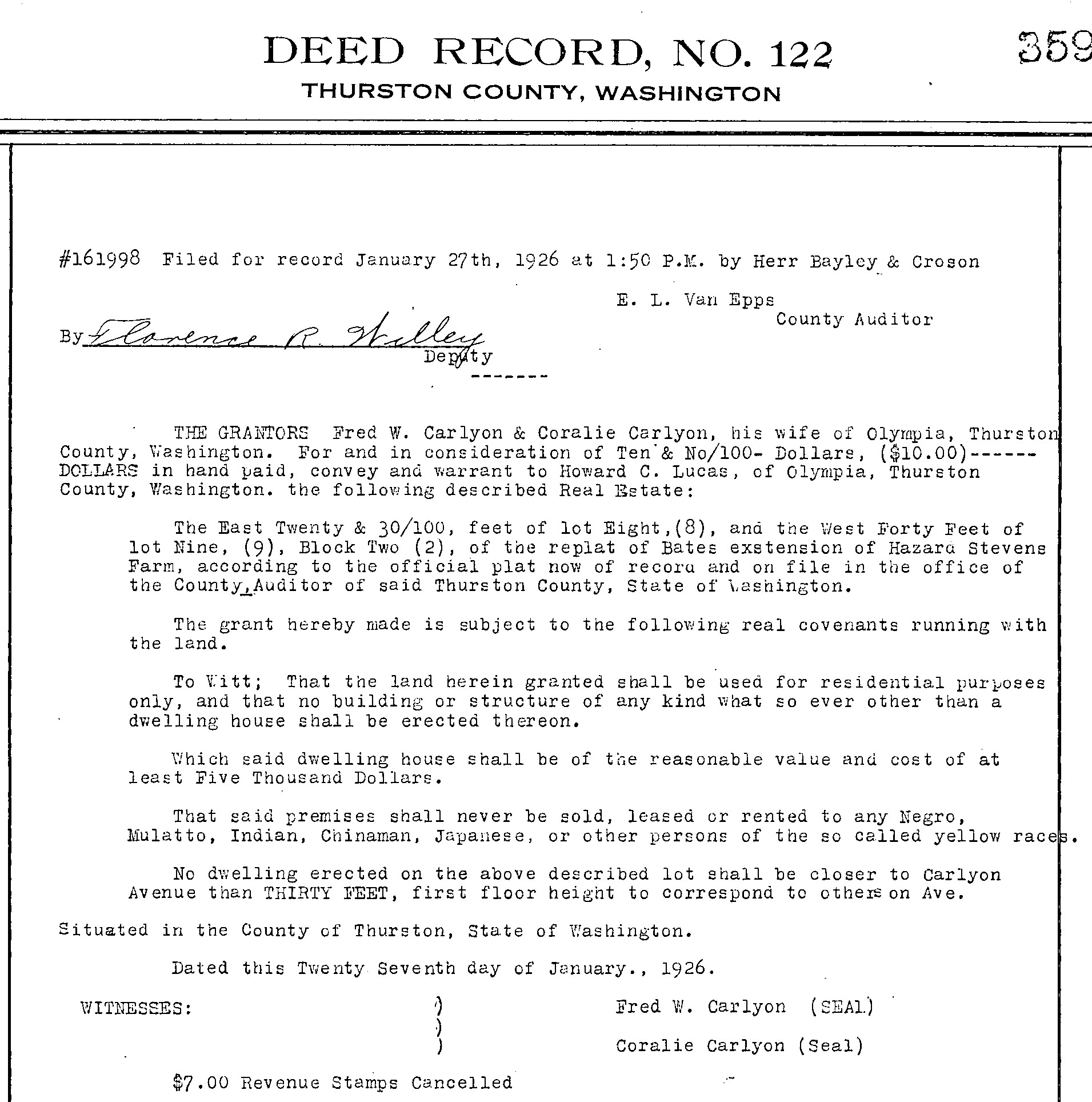

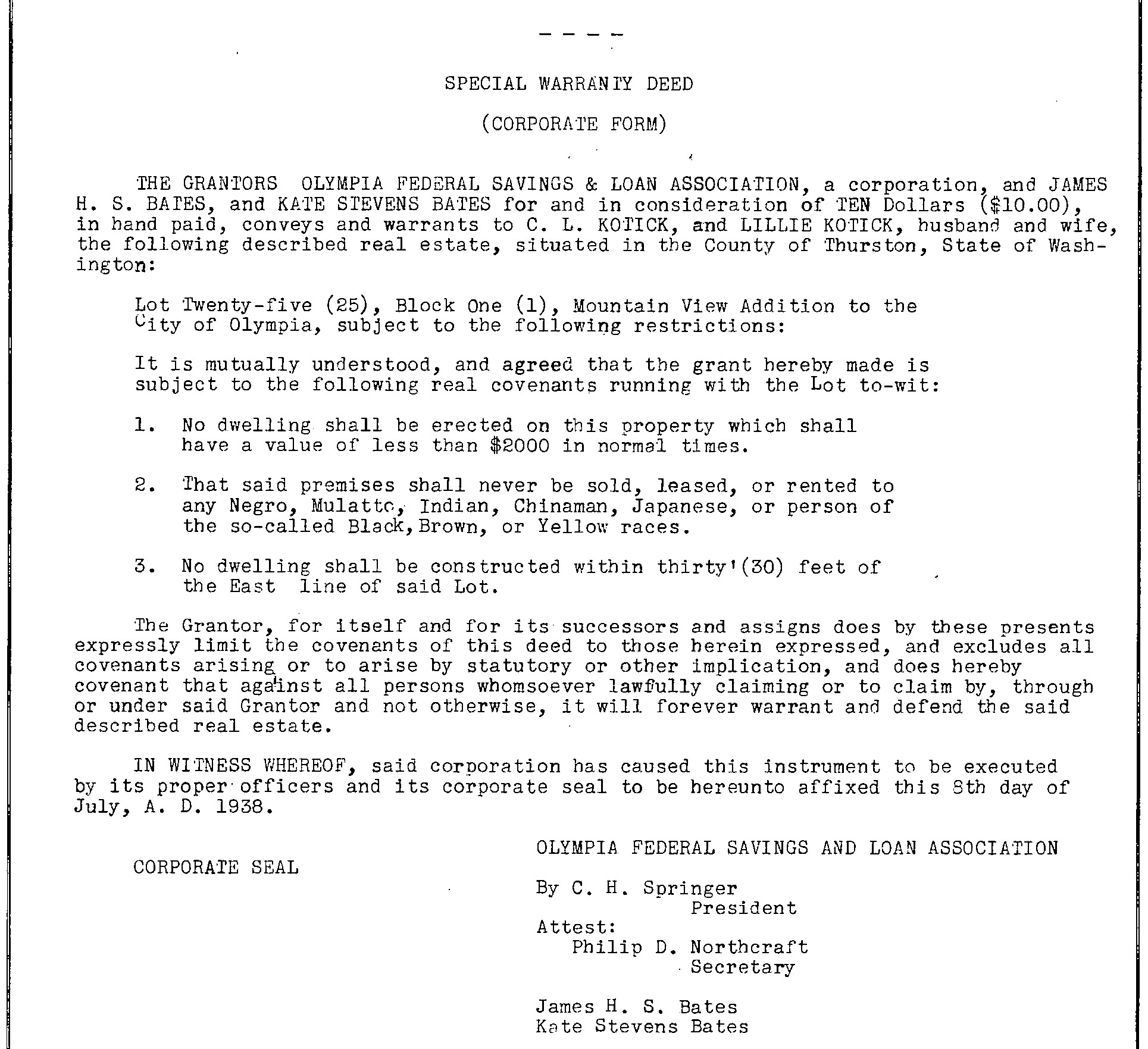

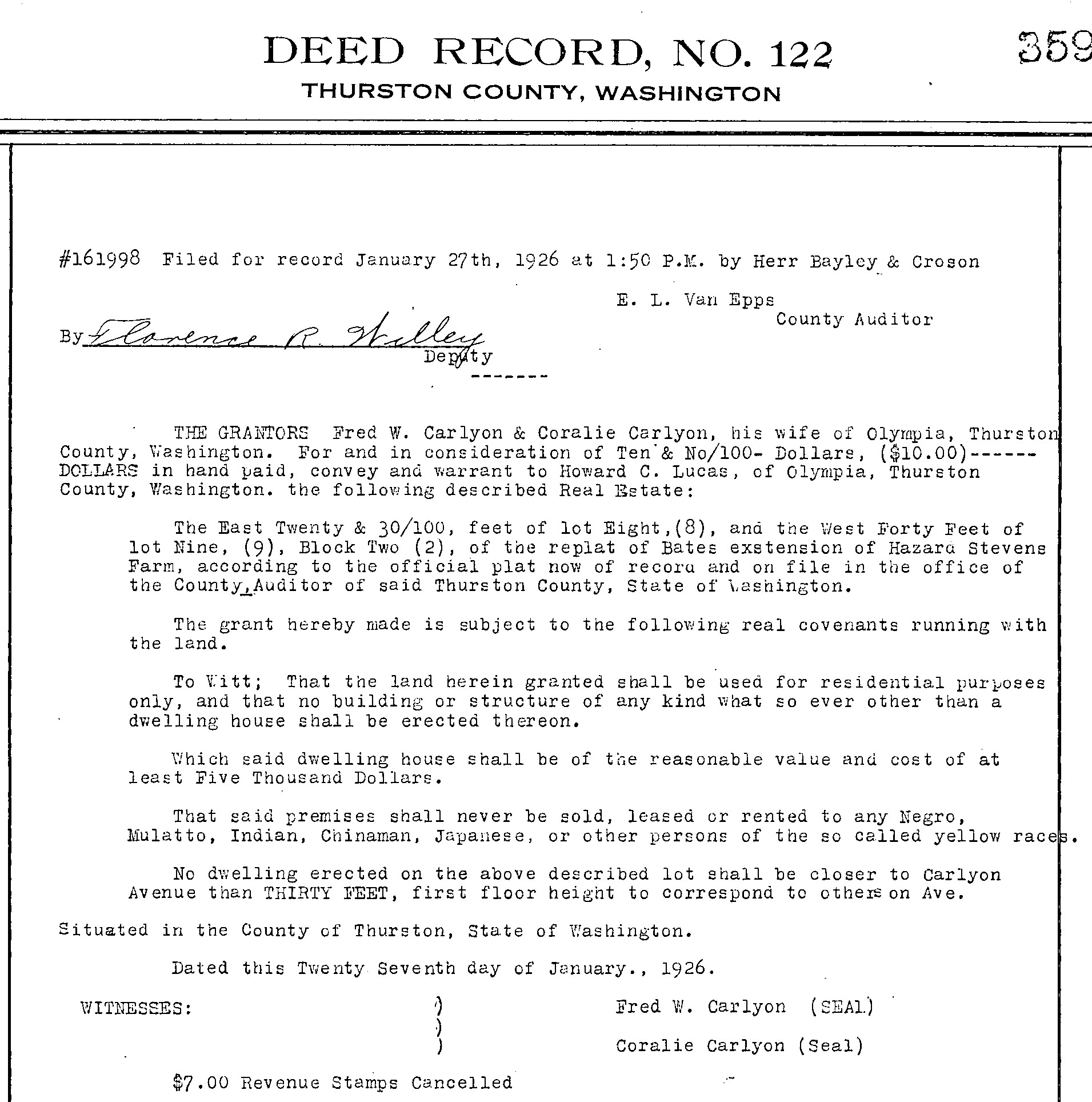

This was one of the first deeds registered with a racial restriction. Fred Carlyon sold this property near the new Capital campus with restriction No. 3 preventing sale or rental "to any Negro, Mulatto, Indian, Chinaman, Japanese or person of the so-called yellow races," terminology that Carlyon would use for hundreds of other properties in the following three decades.

This was one of the first deeds registered with a racial restriction. Fred Carlyon sold this property near the new Capital campus with restriction No. 3 preventing sale or rental "to any Negro, Mulatto, Indian, Chinaman, Japanese or person of the so-called yellow races," terminology that Carlyon would use for hundreds of other properties in the following three decades.

Fred Carlyon was the first to impose racist deed restrictions. Anticipating the construction of the new state capitol building, the wealthy developer registered a racially restrictive covenant on two blocks of properties southeast of the state capitol campus planning to subdivide and sell the land to prospective home buyers. The document stipulated a list of banned populations in terms that would be widely used over the next three decades: “said premises shall never be sold, leased or rented to any Negro, Mulatto, Indian, Chinaman, Japanese or person of the so-called yellow races.” Carlyon went on to develop many subdivisions in the following decades, ultimately restricting hundreds of properties in Olympia from specific racial and ethnic groups.

The accompanying map shows where our team has identified racial restrictive covenants. During the 1920s and 1930s most followed Carlyon’s lead and were imposed in what became the Stevens and Carylon neighborhoods in South Olympia. With World War II, realtors and developers were more likely to restrict new subdivisions. Thousands of Black soldiers were stationed at nearby Fort Lewis during the war setting off alarm bells in nearby White communities in Pierce and Thurston Counties. Thurston’s White supremacy practices proved more effective than Pierce and King which experienced dramatic increases in African American populations. By 1950, Thurston’s Black population had increased by exactly eight individuals -- from 33 in 1940 to 41 ten years later!

The new covenants were part of this “Whites Only” defense. New subdivisions in South Olympia were platted with restrictions, and some in West Olympia, Tumwater, and Lacey.

There was a logic to the geography shown on the map. Older residential neighborhoods were difficult to restrict. To do so each owner of property on a block would need to notarize and file an amendment to their property record. This happened in some older neighborhoods in Seattle as neighborhood associations organized petition campaigns. But we have not found examples in the central areas of Olympia. Doubtless that was because White residents calculated that it was not worth the effort; that realtors and local authorities had other ways to dissuade people of color from attempting to move into all White neighborhoods.

It was less complicated to restrict properties when a subdivision was initially created. Some developers included racial restrictions in the original plat filed with the county auditor, or in a “Declaration of Covenants” filed separately. Others sold properties one by one with the racial restriction in each deed. Either way, the restriction would be forever binding, preventing future owners and future sellers from violating its provisions.

Restrictor spotlight

Efforts to restrict Thurston County were led by some of the most prominent residential developers, business owners, politicians, and residents – many of whom locals will recognize as street and neighborhood names across Olympia, Tumwater, and Lacey. Below are profiles of some of the notables who led efforts to restrict and exclude.

Carlyon

What are now the Stevens and Carlyon neighbors were the first areas to be restricted in the 1920s and 1930s.

What are now the Stevens and Carlyon neighbors were the first areas to be restricted in the 1920s and 1930s.

Fred Carlyon and his wife Coralie imposed the first explicit racial restrictions we have identified in Thurston County, including entire neighborhoods of Olympia, such as the “Carlyon North” neighborhood and North Carlyon Street, both of which still bear the notorious Carlyon name. Between 1926 and Fred Carlyon’s death in 1956 the couple restricted at least 256 properties in various neighborhoods of Thurston county using explicit and offensive racial language.

A jeweler and prominent real estate developer who made his first fortune in Alaska, Carylon benefited from his brother Phillip’s political influence after returning to Olympia in 1923. Serving in the legislature from 1913-1929, Phillip Carylon was President pro tempore of the state Senate when he helped choose the site of the new capital campus.

While most restrictive covenants across the state excluded those who were not “white or caucasian,” the language of this first Carlyon restriction set a precedent for uniquely explicit and descriptive restrictions, demonstrating not only the drive to restrict, but the specific racial attitudes that informed racial exclusion during the late 1920s. The Carlyons' restrictions stipulated that, “... said premises shall never be sold, leased or rented to any negro, mulatto, Indian, Chinaman, Japanese or person of the so-called yellow races.” This outdated and offensive language was used to describe all Black and mixed race people, East Asian people, or native Squaxin and Nisqually people who were pejoratively referred to as “Indians”.

After restricting properties across Olympia’s downtown and various tideland residential enclaves, Carlyon turned his sights to the scenic Steamboat Island area. Fred Carlyon formed the Carlyon Beach Development Company and began development of a private and restricted residential area northwest of downtown. When Carlyon passed in 1956, the Carlyon Beach Country Club took over the project, which was completed in 1959 and used the same restrictive language as Carlyon's initial development. 2020 census tracts from each of Carlyon's restricted developments show less than 1% Black population to this day, reflecting the ongoing impact of restrictive covenants on legacies of homeownership and housing segregation in Thurston County.

What are now the Stevens and Carlyon neighbors were the first areas to be restricted in the 1920s and 1930s. (Courtesy Sophie Belz)

What are now the Stevens and Carlyon neighbors were the first areas to be restricted in the 1920s and 1930s. (Courtesy Sophie Belz)

Stevens/ Bates

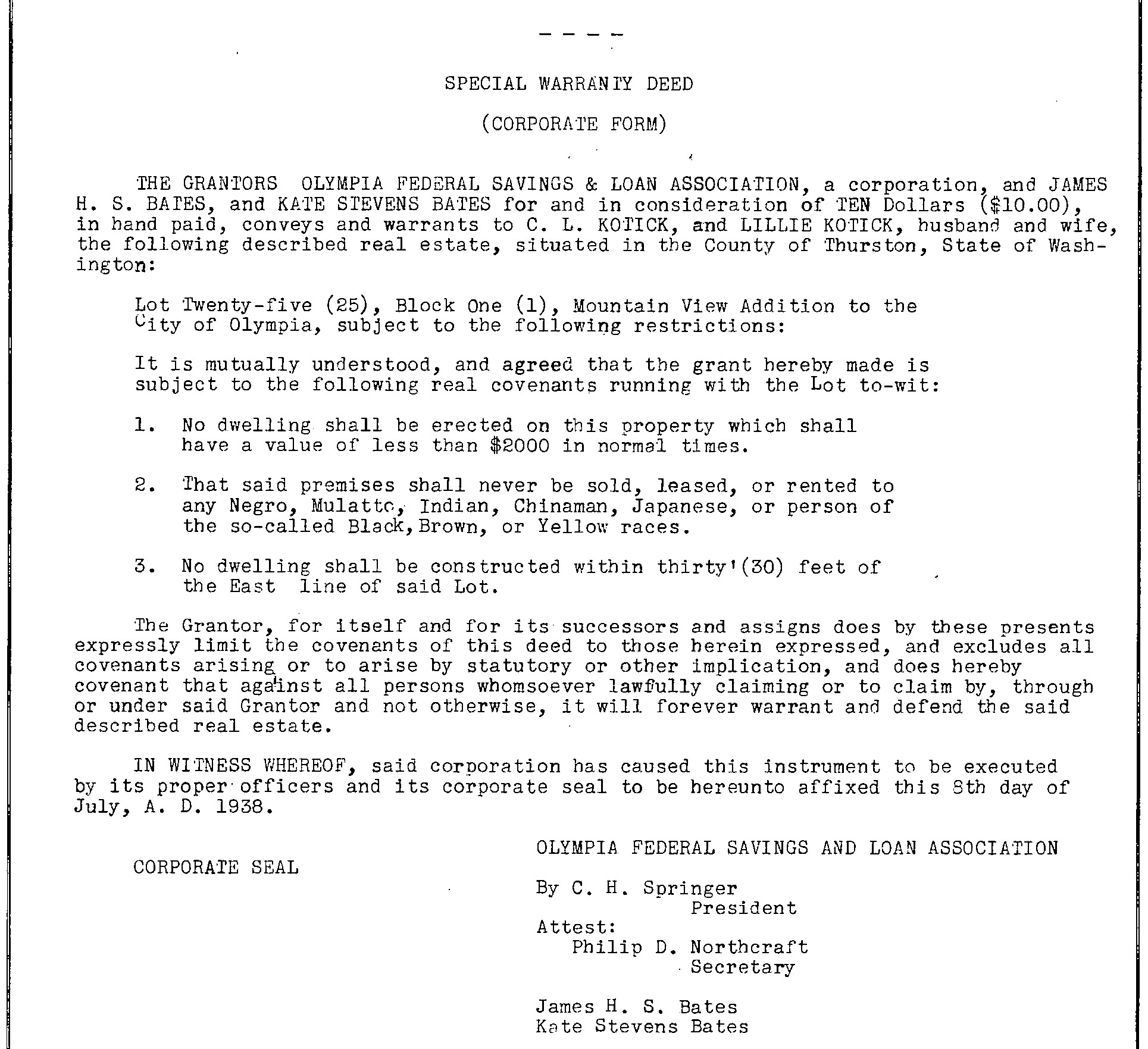

Kate Stevens and her husband James H.S. Bates began their own restrictive legacy with a covenant covering 20 properties in the newly developed Bates-Murno subdivision in 1929. Kates Stevens was the daughter of Isaac Stevens, Washington’s first territorial governor. As governor, Stevens dictated the Treaty of Medicine Creek which expropriated over 90% of traditional Squaxin and Nisqually territories. He designated Olympia as the territorial capital and claimed hundreds of acres for his own estate.

Kate Stevens married her second husband James Bates in 1913, and in 1929 the couple continued her father’s legacy of racial segregation and exclusion. After developing 20 restricted properties in 1929, in 1935 the Stevens-Bates’ restricted an additional 83 properties on the Bates extension of Hazard Stevens Park north of downtown, which had been developed by Kates’s brother Hazard Stevens. Over the span of a decade, Kate and James imposed over 100 racially restrictive covenants on properties throughout Olympia and Tumwater. Despite this legacy, the Stevens-Bates family is widely renowned as one of the most prominent historical families in the Olympia area, and the Old Stevens Mansion still stands as a historical landmark celebrating the family’s brief two year occupancy of the property.

Olympia Federal Savings

1928 deed for properties sold and restricted by Olympia Savings and Loan

1928 deed for properties sold and restricted by Olympia Savings and Loan

Kate Stevens and James Bates began working with the Olympia Federal Savings and Loan Association in 1938 to restrict an additional 105 properties at Mountain View Addition in south Olympia to White residents only. The bank, along with the Bates-Stevens’ restricted properties under the condition that “said premises shall never be rented, sold, or leased to any Negro, Mulatto, Indian, Chinaman, Japanese, or any the so-called black, brown, or yellow races”, employing similar language and racial categories to Carlyon.

Olympia Federal Savings and Loan Association was started in 1906 just as the economy of the city began to grow. It was founded by real estate agents James McDowell and Charles Springer; McDowell serving as the president until 1951. Prior to opening the bank, founder Charles Springer co-owned the Springer and White Mill, which opened in 1887. The loan association provided loans to White residents looking to start businesses, develop property, or purchase homes. Ethel Terry recalls that in the 1950s “Olympia was very much segregated,” and it was almost impossible for Black business owners to obtain bank loans. When she opened a cajun creole restaurant, “Lagniappe Cafe,” Terry recalls, “banks did not want to help Black businesses with finances.” adding, “I think that's one reason why more Black people have not opened businesses in this area.”[5] To this day, Black businesses in Thurston County are underrepresented in the city center, and often relegated to Lacey, outside the main hub of commerce and gathering. [6]

Schmidt/ Olympia Brewing

The founders of another iconic Olympia company, the Olympia Brewing Company, were also heavily involved in racially restricting new developments in Thurston County. In 1896 Leopold Schmidt founded the Capitol Brewing Company (changed to Olympia Brewing Company in 1902) which was, aside from the prohibition era, an iconic symbol of the region and a consistent employer in the area until the early 2000s.

In 1928, Leopold’s son Theodore Franck Schmidt developed 24 properties in Stratford Park dictating that, “No race or nationality other than the Caucasian race shall use or occupy any building on any lot, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants, or a different race or nationality, employed by an owner or tenant.” In 1938 Leopold’s other son, Frederick Schmit restricted an additional 35 properties in Stratford Park and Stratford Park Annex with the same criteria.

Decades later, the Olympia Brewing Company finally agreed to employ a few Black workers. Phil Roberts arrived in Thurston County in 1964 after serving in the military at Ft.Lewis. He became the first African American employee of the the company, and his wife Thiola recalls that “The Olympia Brewing Company hired a head-hunter agency to search for the “perfect” Black employee. After extensive interviewing by the Brewery president and days of meetings by the Union, Phil satisfied the company’s exhaustive criteria and was hired. But then came the housing chllenge. Thiola recalls harassment from two White neighbors who opposed the Black family’s presence in the Tumwater neighborhood.[7]

Two years later, in 1966, Marvin Lamar Brown was hired as a welder at the Olympia Brewing Company, but soon was dismissed from the position when employers realized his race. That was not the only problem. Brown recalls that when he and his wife’s daughter Misty was born at St. Peter Hospital several nurses refused to provide care to the mixed-race child, referring to her only as the “little brown baby.” Clearly, it wasn't only leaders of industry and development who held and perpetuated derogatory racial attitudes - racial prejudice was ubiquitous throughout the culture of Thurston County.[8]

1950s: Post War Racial Exclusion

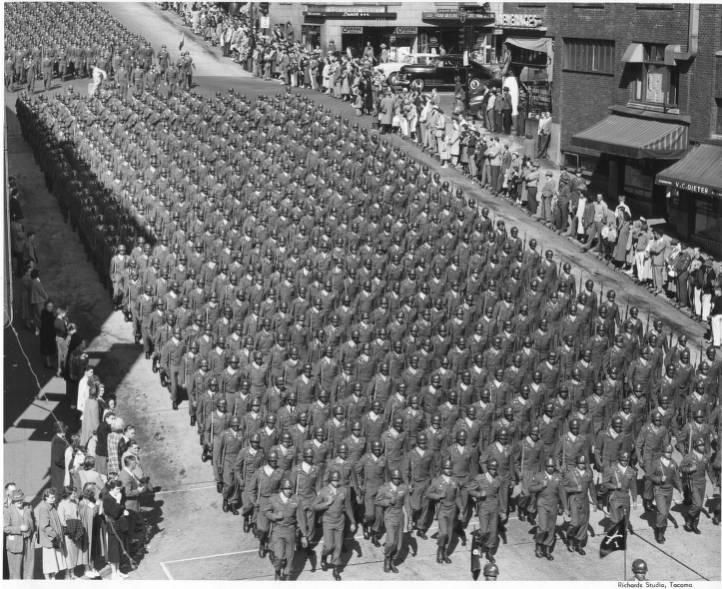

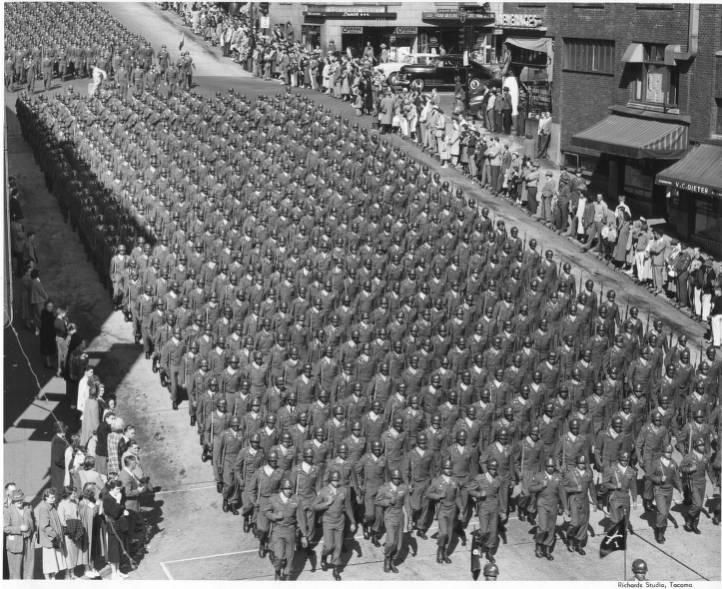

Black troops parade in Tacoma 1950. Thousands of Black soldiers served at Fort Lewis during World War I, World War II, the Korean and Vietnam wars. Until 1954, they served in segregated units and lived in segregated barracks. At Fort Lewis the Black section of the base was located in the south, but despite the proximity few of the accompanying families were able to live in Thurston County. (courtesy: Tacoma Public Library)

Black troops parade in Tacoma 1950. Thousands of Black soldiers served at Fort Lewis during World War I, World War II, the Korean and Vietnam wars. Until 1954, they served in segregated units and lived in segregated barracks. At Fort Lewis the Black section of the base was located in the south, but despite the proximity few of the accompanying families were able to live in Thurston County. (courtesy: Tacoma Public Library)

During World War II and the Korean War thousands of Black soldiers served at Fort Lewis and later some moved to growing Black communities in Tacoma or Seattle. Very few felt welcome in Olympia or Thurston County. The 1950 Thurston County census reported only 299 nonwhite residents (41 Black) in a population of almost 45,000. These numbers barely moved in the 1950s. In 1960, the county remained 99% White with 372 Indigenous Americans, 68 Black Americans and 250 Asian Americans. Some nonwhite families had tried to live in Olympia during the immediate postwar decade but found the racially exclusive and segregated county unbearable and soon left to join larger communities in Tacoma or Seattle.

In the 1950s, there were few Black owned businesses, no Black churches, and no Black organizations that retain records. While some Black people in Olympia attended White churches and institutions, many felt unwelcome.

1927 postcard view of new Capitol and Olympia(courtesy: Washington State Archives)

1927 postcard view of new Capitol and Olympia(courtesy: Washington State Archives)

Dr. Thelma Jackson (Blacks in Thurston County)

The difficulties facing Black folks in the area are detailed in a 2022 book by Dr. Thelma Jackson, Blacks in Thurston County 1950 to 1975: A Community Album. A Thurston resident since 1971. Dr. Jackson explores Black life and resistance to ongoing racial violence and discrimination in a collection of short biographies and oral history interviews of people of who either settled in the county or lived there for a time and left. The following accounts are all based on Dr. Jackson’s interviews.

When Avis and Melba Dennis arrived in Olympia in 1945, Avis had recently received his Masters in Engineering from the University of Washington, and was hired as an engineer with the Washington State Highway Department Toll and Bridge Division. Despite his qualifications, his boss consistently assigned him to tasks below his skill level, and underpaid him for his work. Amidst this, Avis, Melba, and their young son were unable to find housing in Olympia, and relied on a local rental property owned by a Black man living in Tenino. Even in areas not formally restricted by racial covenants, Black people were shut off from viewing, renting, or purchasing property in most neighborhoods of Olympia. The harassment Avis faced came to a head in 1949 when at a department christmas party a coworker dressed in blackface and acted out a one-man minstrel performance for the staff. When Avis met with the personnel director John M. Darling about the incident, he recounts being told “I showed that I was sensitive, and a poor sport”. In 1954 he requested a transfer to Tacoma, which had a larger Black population. When the transfer was approved, the Dennis family left Olympia. [9]

Black residents were denied service at many Thurston County banks, lending companies, restaurants, business, and churches. Ethel Terry recounts a 1953 incident while working as an officer at Madigan army hospital, “ I remember we came from Madigan to eat at the Oyster House Restaurant and I was not accepted as part of the group… We were going to leave but the rest of the group who were with me said they wouldn't eat unless I could eat, so we all were seated and ate finally.”[10]

Freddie Neal, who moved to Rodchester, Thurston County nearly 20 years later in 1957, recounts similar exclusion as the only Black family in that area. Despite being recruited by the Rochester school superintendent, when Freddie arrived to teach, the school district refused to consider assigning her to schools their children attended. She was also denied housing and forced to live in an extra room in the superintendent's home for months.[11]

John Grace, who first arrived in Olympia in 1962, traveled over 100 miles by bus to Portland, Oregon every Sunday to attend a primarily Black church there because he, along with many other Nlack residents, felt unwelcome in Olympia faith communities. Others traveled north to Tacoma to join larger Black churches and civic organizations like the Urban League, which organized for civil rights and social services.[12]

Mary Jackson-Wilson moved to Olympia with her husband Jimmy, an engineer at Fort Lewis, in 1957 and was unable to find housing for nine months, “No one of color was being shown real estate in Olympia in 1957. I did not see another [Black] person when I came.” Only with the help of a White friend who toured apartments for the couple were they eventually able to secure housing. Even then, Wilson remembers, “Some of the neighbors heard we were going to be moving in. And they proceeded to get a petition and went house-to-house to get the petition signed.” Fortunately, Jimmy “...went house-to-house and let them know he would be bringing in an attorney.” But that was not the end of the matter. The family was continuously terrorized by neighbors who assaulted the house with eggs, and burned crosses on the young family’s lawn. Mary and Jimmy were so frightened by the violence they faced that Mary recounts, “My husband got this little gun because we had received threatening letters. He took me out to the range and taught me how to shoot.” The family was ultimately driven away by the racial terrorism of their neighbors, and moved from the Thurston area in 1960.[13]

Resistance/Change

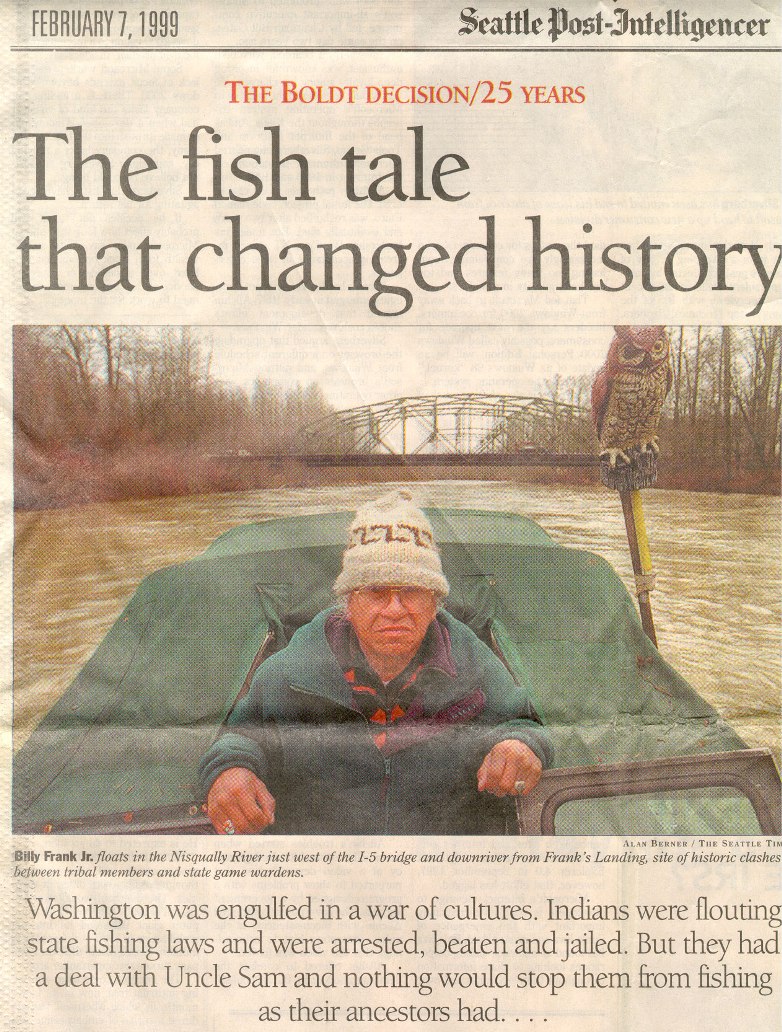

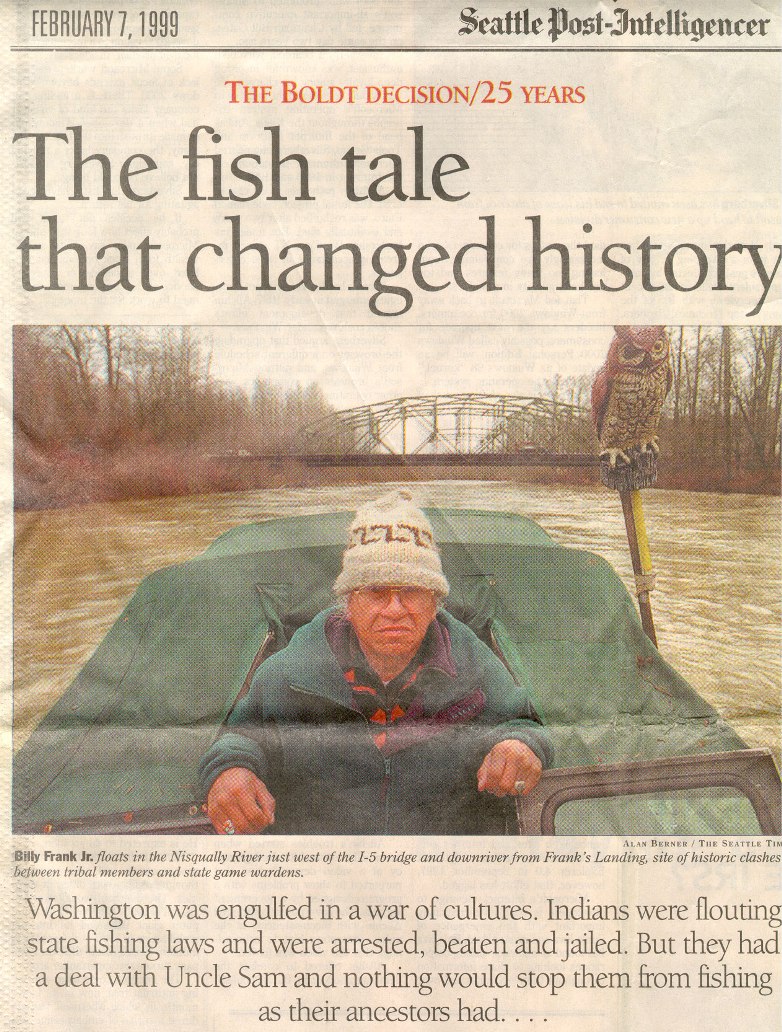

Billy Frank Jr. photographed in 1999, twenty five years after the federal court decision that finally restored tribal fishing rights.

Billy Frank Jr. photographed in 1999, twenty five years after the federal court decision that finally restored tribal fishing rights.

The 1960s saw the beginnings of demographic change, mostly in the expanding Asian American population which reached nearly 1,000 in 1970, counting bi-racial children. Tribal populations had increased to 582 and 207 Black Americans lived in Thurston, mostly sprinkled in racially segregated pockets across areas of west Olympia, the east side, and south in Tumwater. The county population remained 98% White.

Efforts to challenge the county’s practices of racial exclusion and racial subordination were not new, but in the mid 1960s, Black and Indigenous activists began to organize in new ways and see an impact. Virgil Clarkson moved to Thurston County in 1965. With difficulty and after exclusionary steering from local realtors Clarkson purchased a home on the corner of Boulevard Ave, recalling, “I was being directed by the realtors I was dealing with at that time to the north side of Olympia, which was destined to become the slum of Olympia. I would not buy any of those.” Clarkson was indignant at the overt racial discrimination he faced in Thurston County. He recalls, “There was no open housing here. Managers of housing units could turn anybody down who they didn't want to live in their facility.” Over the next decade he became a primary organizer of the local open housing campaign.[14]

Seattle passed an open housing ordinance shortly after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr in 1968, just days before Congress passed the national Fair Housing Act. Local activists were determined to see Thurston cities pass similar legislation. Clarkson and others, “...started an effort to gather signatures to get open housing in the various communities.” he recalls, “We did that on Thursday and Friday. On those two days, we feathered a little over two thousand signatures.” Clarkson took the petitions to city call, where they were quickly passed first in Lacey then Olympia. The legislation passed more slowly in Tumwater, Tenino, and other small towns, "because they said they didn't have a problem!” Clarkson remembers. Virgil Clarkson went on to take public office in Lacey in 1998, and became the city’s first Black mayor for two consecutive terms from 2004-2007, and again from 2012-2013.[15]

Fish wars

Indigenous activists fighting a parallel but different struggle for tribal sovereignty and control of resources that had been guaranteed in the 1854 treaties were increasingly effective in the 1960s. Northwest tribes demanding their right to fish in the so-called Fish Wars involved many peoples and locations, but the key battles were fought in Thurston and Pierce Counties by members of the Nisqually, Puyallup, Squaxin and other southern Puget Sound nations. After years of harassment and arrests by state fish and game wardens, radical activists formed the Survival of the American Indian Society (SAIA) and conducted a series of dramatic fish-ins starting in 1964, earning massive publicity while they openly defied state authorities and went to jail. Many of these confrontations occurred at Frank's Landing, near the Nisqually reservation and were led by Janet McCloud (Tulalip), along with Billy Frank Sr. and Billy Frank Jr. (Nisqually).[16]

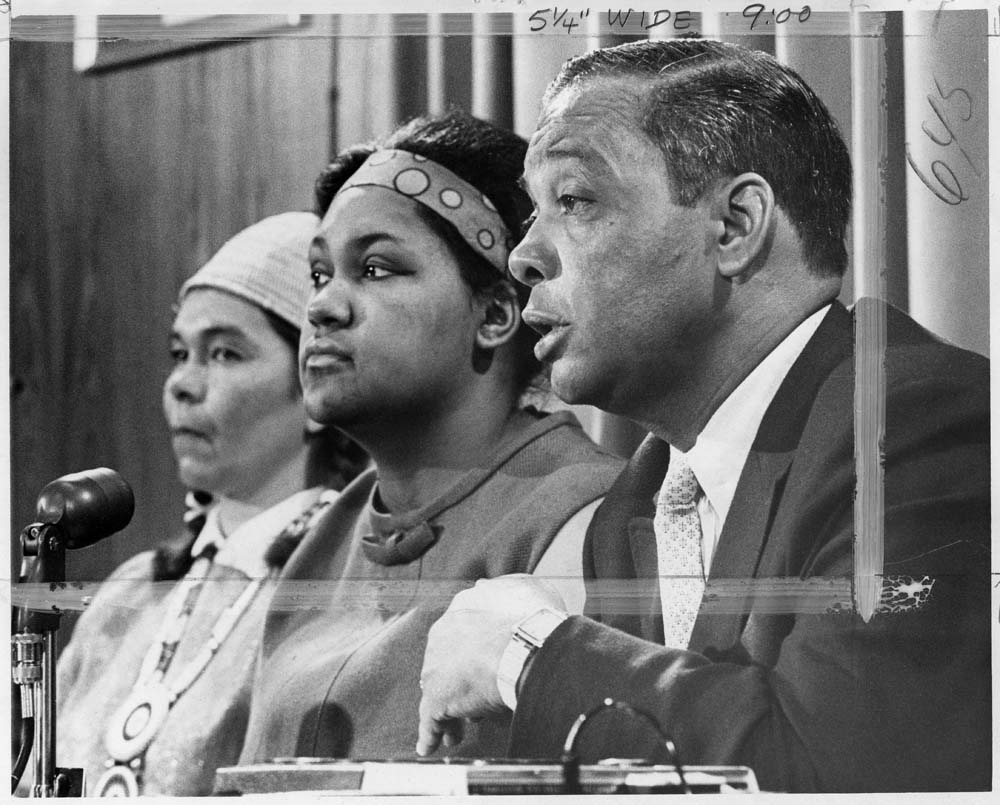

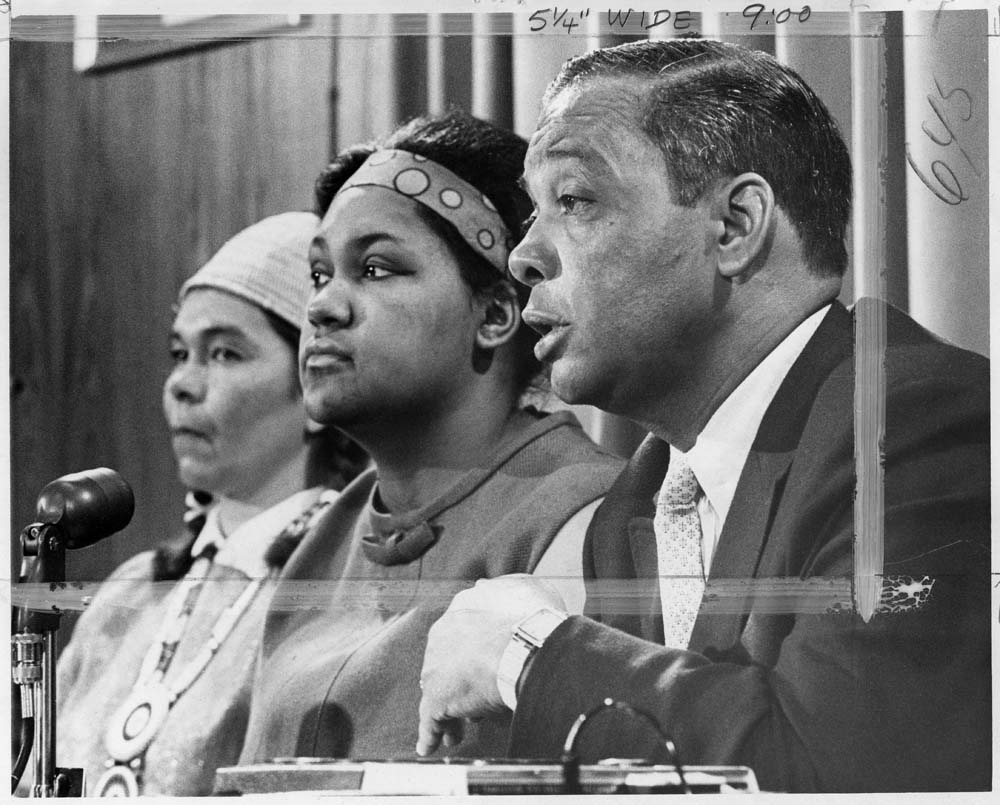

Janet McCloud, Lillian Gregory, and Jack Tanner at 1966 press conference demanding the release of Dick Gregory and others arrested at a Frank's Landing fish-in (courtesy: Tacoma Public Library)

Janet McCloud, Lillian Gregory, and Jack Tanner at 1966 press conference demanding the release of Dick Gregory and others arrested at a Frank's Landing fish-in (courtesy: Tacoma Public Library)

Key support for the fish-in struggle came from Jack Tanner, director of the state NAACP, who in his role as a civil rights attorney defended many of the activists in court and in testimony before the state legislature. The links between Black and Indigenous civil rights struggles was also symbolized by the 1966 arrest of Black comedian and activist Dick Gregory who had participated in an illegal fishing action at Frank's Landing. The struggles achieved a momentous court victory in the 1974 Boldt decision which established the federal court precedent for the recognition of tribal sovereinty and the recovery of resources guaranteed to tribes across the United States in 19th century treaties.

By 1980, the culture and demographics of Thurston County was beginning to change. In 1980 Thurston County was home to over 124,000 residents, 1,019 of them Black, nearly 2,500 of Asian or Pacific Islander ancestry, and 1,726 Indigenous. But if there were now cracks in the patterns of racial exclusion, segregation remained mostly in place despite the new laws. Census tract records show that in 1980 nearly all Black residents lived in Lacey, which had been incorporated 15 years earlier. Elsewhere, neighborhoods and properties restricted in the previous four decades remained almost entirely White. Change came slowly to Thurston County.

In recent decades Thurston County has become more diverse, but the legacies of more than a century of active and intentional racial exclusion practices are not easily erased. As of 2020, many neighborhoods iremain nearly all White, while Black and Latino residents are concentrated in Lacy and eastern parts of the county. The number of African Americans is barely above 3% of the population. And, as our charts show, there are intractable differences in homeownership rates and the many related opportunities that come with homeownership.

Sophie Belz was Senior Research Associate for the Racial Restrictive Covenants Project 2023-2025

1927 postcard view of new Capitol and Olympia (courtesy: Washington State Archives)

1927 postcard view of new Capitol and Olympia (courtesy: Washington State Archives)  Chief Quiemuth of the Nisqually people was the elder brother of Chief Leschi. Despite surrendering to Gov Isaac Stevens, he was murdered while in custody. The artist and date of this sketch is unknown (courtesy: Washington State Historical Society)

Chief Quiemuth of the Nisqually people was the elder brother of Chief Leschi. Despite surrendering to Gov Isaac Stevens, he was murdered while in custody. The artist and date of this sketch is unknown (courtesy: Washington State Historical Society)  Courtesy Washington State Historical Society and Olympia Historical Society

Courtesy Washington State Historical Society and Olympia Historical Society  The new Capital buildings and campus were under construction starting in 1922. Fred Corlyon and Kate Stevens Bates were among the developers taking advantage of the redesigned Capital to open new subdivisions in what had been farm land southeast of the Capital grounds. (courtesy: Washington State Archives)

The new Capital buildings and campus were under construction starting in 1922. Fred Corlyon and Kate Stevens Bates were among the developers taking advantage of the redesigned Capital to open new subdivisions in what had been farm land southeast of the Capital grounds. (courtesy: Washington State Archives)  Click map image to see interactive map of 1700 restricted properties

Click map image to see interactive map of 1700 restricted properties  This was one of the first deeds registered with a racial restriction. Fred Carlyon sold this property near the new Capital campus with restriction No. 3 preventing sale or rental "to any Negro, Mulatto, Indian, Chinaman, Japanese or person of the so-called yellow races," terminology that Carlyon would use for hundreds of other properties in the following three decades.

This was one of the first deeds registered with a racial restriction. Fred Carlyon sold this property near the new Capital campus with restriction No. 3 preventing sale or rental "to any Negro, Mulatto, Indian, Chinaman, Japanese or person of the so-called yellow races," terminology that Carlyon would use for hundreds of other properties in the following three decades.  What are now the Stevens and Carlyon neighbors were the first areas to be restricted in the 1920s and 1930s.

What are now the Stevens and Carlyon neighbors were the first areas to be restricted in the 1920s and 1930s.  What are now the Stevens and Carlyon neighbors were the first areas to be restricted in the 1920s and 1930s. (Courtesy Sophie Belz)

What are now the Stevens and Carlyon neighbors were the first areas to be restricted in the 1920s and 1930s. (Courtesy Sophie Belz)  1928 deed for properties sold and restricted by Olympia Savings and Loan

1928 deed for properties sold and restricted by Olympia Savings and Loan  Black troops parade in Tacoma 1950. Thousands of Black soldiers served at Fort Lewis during World War I, World War II, the Korean and Vietnam wars. Until 1954, they served in segregated units and lived in segregated barracks. At Fort Lewis the Black section of the base was located in the south, but despite the proximity few of the accompanying families were able to live in Thurston County. (courtesy: Tacoma Public Library)

Black troops parade in Tacoma 1950. Thousands of Black soldiers served at Fort Lewis during World War I, World War II, the Korean and Vietnam wars. Until 1954, they served in segregated units and lived in segregated barracks. At Fort Lewis the Black section of the base was located in the south, but despite the proximity few of the accompanying families were able to live in Thurston County. (courtesy: Tacoma Public Library)  1927 postcard view of new Capitol and Olympia(courtesy: Washington State Archives)

1927 postcard view of new Capitol and Olympia(courtesy: Washington State Archives)  Billy Frank Jr. photographed in 1999, twenty five years after the federal court decision that finally restored tribal fishing rights.

Billy Frank Jr. photographed in 1999, twenty five years after the federal court decision that finally restored tribal fishing rights.  Janet McCloud, Lillian Gregory, and Jack Tanner at 1966 press conference demanding the release of Dick Gregory and others arrested at a Frank's Landing fish-in (courtesy: Tacoma Public Library)

Janet McCloud, Lillian Gregory, and Jack Tanner at 1966 press conference demanding the release of Dick Gregory and others arrested at a Frank's Landing fish-in (courtesy: Tacoma Public Library)