At the 2021 Discovery Conference, Kristoffer Rhoads, PhD, laid out the complex landscape of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), including options for evidence-based prevention and treatment, in a thorough overview for health care professionals.

What is MCI?

Kristoffer Rhoads, PhD, Associate Professor of UW Neurology

Even though 94% of providers will say that MCI is a critically important issue to be assessing, diagnosing, and treating, only 45% have any standard protocol or guidance for dealing with this issue or even talking about MCI with their patients. Kristoffer Rhoads, PhD, Associate Professor of UW Neurology and a neuropsychologist at the MBWC, aims to better prepare those in the position to provide earlier detection and care within this window of opportunity to protect brain functioning and plan for the future.

MCI is the "gray zone" between normal aging and the major functional changes of dementia, a period lasting one to 10 years. In normal aging, Rhoads explained, many cognitive functions do not significantly change from ages 20- 80. These are cognitive domains as verbal abilities, mental math, working memory, and long term memory, especially memory for facts and "how to do things." But, the speed at which we process information decreases over time, which can affect executive functioning and short-term memory.

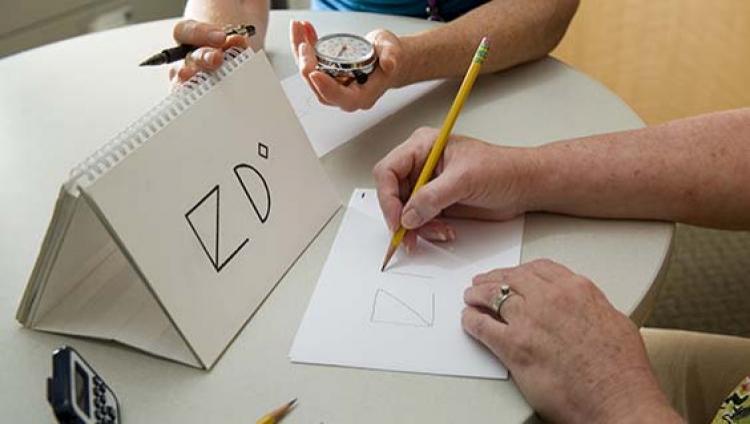

In contrast, people living with MCI show noticeable decline in middle age. Only a physician can diagnose MCI, using objective cognitive tests that show a decline in a person’s performance from the past. People living with MCI continue to function independently in their daily lives, but they may need some help with complex functional tasks. For example, people with mild cognitive impairment may take a little while longer to handle paying bills or prepare a meal.

By the Numbers

Five million American live with MCI. Half of all MCI cases are estimated to be due to the early manifestations of Alzheimer's, but not all MCI progresses to dementia. About 10% revert to normal aging within a year after treatment for conditions such as sleep apnea, depression, or over-medication or high alcohol consumption. Other MCI cases, especially if the MCI affects non-memory cognitive domains, are due to other conditions, such as frontotemporal degeneration, Lewy Body disease, or vascular cognitive impairment.

In the US, among people over age 45, 15 million report 'subjective cognitive impairment', meaning that a person senses they are developing some mild problems with memory and thinking, but the decline is not showing up on cognitive diagnostic tests. "One thing we wrestle with is whether these individuals are hypervigilant and noticing normal age-related changes," said Rhoads. "But, we do know that people are extraordinarily good at detecting changes in their own cognition before our standard tests can pick them up, particularly if you are not from a group on whom those tests were normed. It's a huge number."

Is Treatment Possible?

Rhoads explained that an early diagnosis of MCI provides the widest window of opportunity to intervene and establish new behaviors and treatment of modifiable risk factors that may improve a patient's outcome.

"We can't prevent the build up of neuropathology completely, but we can slow down the accumulation in the brain. The thinking is, if we can do that, we can maintain the structural integrity of the brain and keep people functioning in the presymptomatic stage of dementia, or, in the worse care scenario, prevent people from reaching late stage dementia and incurring the greatest care costs and loss of function."

He pointed to the recent findings from the SPRINT-MIND study, which found that lowering blood pressure to under 120 showed a 19% reduction in those participants who went on to develop dementia during the study. A 2015 study of 65 sedentary adults showed that working up a sweat for 45 minutes, 4 times a week reduced tau protein in the brain and improved memory, attention and executive function.

Evidence-based exercise recommendations for people living with MCI:

Rhoads emphasized that it is always important to check with a health care provider about any new exercise program, and that it is critical to start slow to avoid injury.

-

30 or more minutes of moderate physical activity at least 5 days per week

-

20 or more minutes of vigorous physical activity at least 3 days per week

-

Exercise can be done in 10 minute bouts (Example: Instant Recess)

-

More complex movements, such as dance or tai chi, are especially beneficial for the brain