By Cuong “TJ” Vu

For more than sixty years, tai chi has been a part of Joe Liao’s life. Growing up in Taiwan, he began studying martial arts at six years old and advanced from student to teacher, eventually to Master after emigrating to the United States and opening up a studio in Burlington, Washington in 1977 to teach tai chi and kung fu. Over the course of the next twenty years teaching his studio classes, Joe welcomed students to learn and practice and cultivate diligence, compassion, balance, integrity, and humility - all with the overarching goal of creating a healthy body and mind.

Joe Liao

In 2018, Master Joe’s students expressed concerns about their treasured teacher’s health and worsening short-term memory, and they gathered to figure out what might be happening to him. Joe soon moved into a memory care facility, The Bellingham at Orchard. Laure Brooks, Master Joe’s student since 2004 and now dedicated care partner, grappled with his dementia diagnosis, saying “we still grieve and are saddened that he’s at a memory care facility instead of his familiar studio.” However, she remembered Master Joe’s persistent encouraging motto: “The way’s the way.”

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit very close to home.

Washington State was identified as the epicenter of a major COVID-19 outbreak, occurring in a long-term facility and quickly spreading to other nursing homes. As a result, visitors to long-term care facilities were banned and family members were forced to communicate and see their loved ones only through windows. Within these facilities, residents were confined to their rooms, group gatherings were cancelled, and meals were delivered to rooms to help control the spread of transmission.

In-person visits and trips that Laure and others had taken with Joe before the pandemic suddenly stopped. He could not longer share his love of tai chi and dance with various communities. With the pandemic forcing him into isolation and lockdown since March, “Joe went into a deep depression and wouldn’t come out of his room, reverting back to speaking mostly his native Mandarin,” Laure recalls. The impacts of lockdown on Joe’s brain health not only created challenges with communication and comprehension, but further compounded feelings of isolation, loneliness, and frustration he and his caregivers were already feeling from the loss of normal connection.

Return of the Master

Master Joe. Courtesy, Laure Brooks

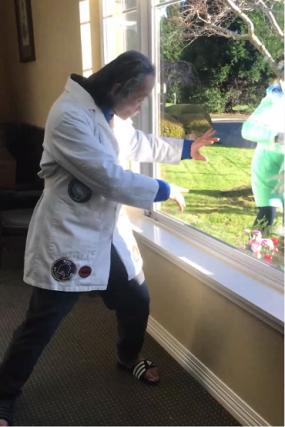

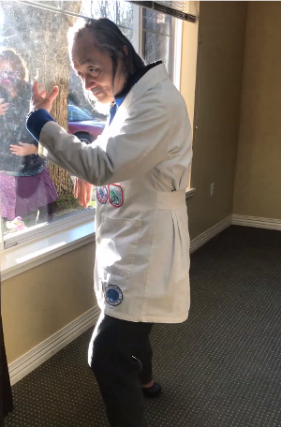

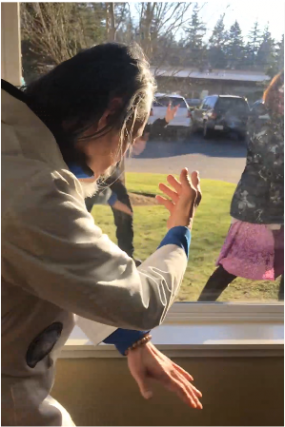

Knowing Joe’s love of music, Laure had an idea to try to engage and connect with him, even as they had to remain physically separate. She advocated and worked with the memory care facility to have window meetings with him outside his room, waving to him through the glass and dancing along to a boombox. Soon after, Laure enhanced the Orchard’s conference room to make Joe feel like he was in his studio again.

She placed familiar objects such as a vase of flowers once located in his former studio and made a playlist of Mandarin music. “My goal was that he could be himself wherever he was, and he would be honored as himself wherever he was, and people wouldn’t be afraid of him,” Laure says. Within this space, Joe transformed back into Master, teaching tai chi classes to facility staff caregivers and residents—and to Laure and former students gathered on the lawn watching him through the conference room window.

Laure and the caregivers at the Orchard have since seen a change in Joe. “He is happier now. He’s singing and coming out of his room like he’s gone beyond the depression and isolation. Now there’s eye contact. There’s corrections; if we have one foot here and one foot there, he indicates how to line up and be balanced, just like he used to.”

Trusting the Process

As word got out about Joe’s tai chi classes through a local newspaper article telling his story and word of mouth spread, Laure worried about the stigma around dementia. How would people react to learning that Joe was now living in a memory care facility? Would people be upset or uncomfortable upon seeing the effects of dementia on Joe, who they had once revered as a Master? He once told people what to do, and no one had really ever told him what to do.

Instead of being fearful, Joe and his son viewed his situation as a way to tell his story, help other people, and continue his lifelong passion of teaching tai chi as a way to improve both physical and mental health. When asked what he thought about him teaching people from the window during the COVID pandemic, Joe responded in English, “it’s wonderful.”

Laure’s initial fears of people withdrawing from Joe or that Joe would be afraid of revealing his dementia to his students or the public quickly resolved. His window tai chi lessons have benefited the community as much as Joe, providing a sense of collective support for one another. Master Joe’s class continually draws an audience, eager to practice tai chi and see Joe continuing to flourish throughout the pandemic.

Joe’s gift goes beyond teaching the graceful art form and mind-body connection. He has taught others the importance of silencing and emptying one’s mind in order to drop all our worries and cares and tap into our natural flow. There was a sign in his studio that read: Enter with Silent Mind. He once said that when he empties his mind, he can connect with every person. “I think Joe is helping us realize we can drop our expectations, inhibitions, perfectionism. When I go to class, I realize I am everything that I need and what Joe needs - just by me showing up. There’s this magic moment when you just trust the process.”

Despite the Dementia, Joe Still Remembers Tai Chi

Even though dementia affects short-term memory, older procedural memories may remain latent and stay intact much longer than people think. Laure believes Joe is still able to teach tai chi, not only because his body remembers tai chi movements, but also because he still has a deep emotional drive to connect with people emotionally.

Courtesy, Laure Brooks

Dr. Kris Rhoads, PhD, a neuropsychologist at Harborview and UW Associate Professor of Neurology, studies procedural memory—or, deep-rooted memories of how to do things, such as dancing or shuffling cards, for instance. He notes that this form of memory is preserved in people living with dementia for much longer than short-term memories. Short-term memory involves a number of brain structures and networks, including the hippocampus and mesial temporal lobes, and while these frequently change in Alzheimer’s, other structures involved in motor or habit memory, such as the basal ganglia, remain intact. This finding suggests that activities that engage these procedural memories, such as tai chi for Joe, can remain meaningful and productive for those with Alzheimer’s disease and their care partners.

“Long-term and procedural memory frequently remain intact areas of strength, particularly in the earlier stages of dementia but also as things progress,” says Dr. Rhoads. “One of our goals is to lean more heavily on these to use good habits and systems to compensate for short term memory loss. Personally meaningful photographs, videos, news stories or footage, and particularly music from earlier times can provide a conduit to memories and joy for people living with dementia. Care partners can facilitate this by providing the time, space, and occasional cue (such as the name of a place or person) while avoiding quizzing or correcting the person with memory loss and meeting them where they’re at in the moment. This can be a challenging process and requires a healthy dose of compassion for all involved, including oneself.”

People with memory disorders can and want to share themselves, their passions, and creativity with others. “Never underestimate what our loved ones can give us and to be looking for their gift, because their essence is still there,” says Laure. “My advice is to reach out to past and present friends and bring back the memories and the essences of that person.” Laure recommends caregivers to keep trying to connect with their loved ones, even at later stages of dementia. Though they may not be able to communicate through words, they may be able to by a hug or squeeze of the hand. Allow and nurture that process.

Window of Opportunity

Courtesy, Laure Brooks.

Connecting with others through tai chi has transformed Joe. It has enabled him to fulfill his life-long purpose to teach and help others learn the ancient art of tai chi for physical and mental well-being. This large picture window not only has now brought him out of the seclusion and loneliness to where he can see the road, cars, as well as life going on, but Laure remembers the empowering change she saw in Master Joe. “I feel like that was kind of where he felt like, ‘Oh, I’m on the stage.’ He’s singing, he’s coming out of his room and he’s gone beyond the depression and isolation.” Definitely, Joe is seeming like the kind of tai chi Master that he always was.

Laure’s main goal was helping Joe reconnect with others. However, she and others would soon realize how much Master Joe was also helping them through the loneliness and disconnection caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. “I think he always was a master, but he was stifled in this new situation and his dementia. He’s taken me to another level, and he’s allowed the people in our class to move to another level of acceptance because they don’t see him fighting ‘what is.’ Seeing him as he is and connecting with where he is now is just so empowering for all of us.” In a way, Joe has reminded Laure and others to accept the current situation the pandemic has created and recognize what we still have rather than what we have lost.

The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown has had a devastating toll on physical and mental well-being for residents of long-term care facilities, just like Joe Liao. Yet, Laure’s resilience and determined advocacy for Joe changed everything, revealing how caregivers and the community can bring about positive and transformative changes. The window that physically barred them from being together became the very thing that connected them. As Master Joe once taught “the way’s the way,” this window of opportunity has taught us it’s possible to find a way to flourish even in a pandemic that ironically disconnects and connects us all. •

About the author:

Cuong “TJ” Vu

Cuong “TJ” Vu (UW ’22) is a pre-med and Biology major and a Junior at the University of Washington. He is a volunteer at the UW Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, where he hopes to gain experience and help those afflicted with memory loss. His drive to help stems from witnessing the condition’s toll on his grandmother’s memory and vitality. Once a fierce pillar of strength who fought her way up as a Vietnamese refugee, she earned her Master’s degree to become a Professor of English Studies. Vu is also motivated by how much this disease affects the Asian population, but also other communities disadvantaged by access to care barriers.