A microscopic image of cells in the human cerebellum. The granular layer (dark area on the right) is composed of small, densely packed granule cells, which process information from the brain and midbrain. Courtesy of Colby Samstag and Mayumi Yagi

Written by Michael McCarthy, UW Medicine

It has long been thought that the human cerebellum, the small structure at the back of the brain, is not affected in Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle now report that a study of patients with Alzheimer’s found atrophy in a layer of cells crucial to cerebellar function.

The granular layer is composed of small, densely packed cells. These granule cells receive signals from many parts of the brain, process them and relay those signals to other areas of the cerebellum.

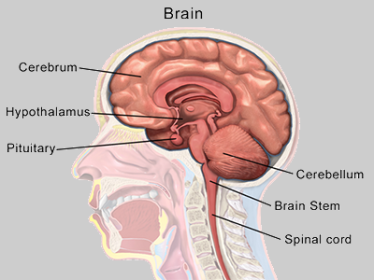

An illustration shows the cerebellum and other parts of the human brain. Bruce Blaus via Wikimedia Commons

“We found that there was atrophy of the granular layer in patients with dementia, and that this atrophy was more pronounced in those with more advanced dementia,” said Dr. Erik Carlson, UW associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

“What’s more, the changes we found in the cerebellum were independent of classical signs of Alzheimer’s, like amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, seen in the rest of the brain, suggesting that these changes in the cerebellum may play an important role in the disease," he said.

Carlson is senior author of the paper, whose findings were published Dec. 23 in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia.

Although the granular layer takes up a relatively small space in the human brain, granule cells account for 60% to 80% of all neurons in the brain, Carlson noted.

The researchers also found that the cerebellums’ weight, in relation to the total brain weight, was also associated with Alzheimer’s severity. Lower relative weights were associated with more severe cases. This association appeared to be independent of the degenerative changes in the cerebrums of patients.

For almost 200 years, the cerebellum was thought to be primarily involved in coordinating movement. In recent years, however, its crucial role in coordinating other mental processes, including emotion and thought, has become clearer. It is understood that damage to the cerebellum, from a stroke, for example, can result in difficulty understanding and producing language and performing executive functions such as planning and abstract reasoning, and cause personality changes.

The exact reason for the atrophy of the granular layer seen in the Alzheimer’s patients is not clear, Carlson said. Close examination of the cerebellums revealed a loss of small, complex structures in the granule layer, called cerebellar glomeruli. These structures are composed of synapses, which are connections between cells that receive signals from other parts of the brain and other granule cells. Loss of these glomeruli would likely severely affect the cerebellum’s ability to process information, Carlson said.

The finding that cerebellar weight was independently associated with severity of Alzheimer’s suggests it might be possible to diagnose the disease using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Carlson said. Currently, the only way to definitively diagnose the disease is to directly examine brain tissue after death.

The finding that greater cerebellar weight was associated with less severe dementia raises the possibility that activities, either physical or mental, that stimulate cerebellar function might help prevent dementia, Carlson said.

“We’re very curious to know whether the cerebellum is plastic enough that such activities could help slow or reverse changes seen with aging.”

The study was done in collaboration with the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute’s Adult Changes in Thought study. In this study, patients are followed over their life course to understand how aging affects health and cognition. Brains of patients who had donated the organs for research were used in this study. This allowed researchers to compare cerebellar changes in individuals who had dementia and those who had not.

Colby Samstag, a research scientist in neurology, is the paper’s first author.

This research was supported by funding from the National Institute for Mental Health (R01MH116883-S1m, R01MH116883), National Institutes of Health (RO1AG075338, 30 AG066509, P50 AG005136, K08 AG065426-05), National Institute on Aging (AG005136, K08 AG065426-05), the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development Medical Research Service awards (1I01BX002311, 1I01BX005984, 1I01RX003829).

The illustration by Bruce Blaus of human brain structures was used under terms of the Creative Commons ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License.