This interview was conducted by MBWC's Genevieve Wanucha and has been edited for length and clarity.

As published in Dimensions Magazine for Fall/Winter 2023.

What brought you to this role of director of clinical trials at the UW Memory and Brain Wellness Center (MBWC)?

Thirty years ago, when I was in high school, I took a trip to Seattle. As soon as I got off the plane, I fell in love with the city. I dreamt of living and working here. But nothing came to fruition over the years.

More recently, I worked at Health Partners in St. Paul, Minnesota for 13 years, as the principal investigator for industry-funded clinical trials and performed my own clinical studies. When I learned about the open position for director of clinical trials at the MBWC, I was very much intrigued by the focus on patient experience and the fact that the University of Washington has a history of innovation and excellence. And because the MBWC is based in Seattle, it seemed like an opportunity where I could have my cake and eat it too.

What do you most appreciate about being part of the MBWC team?

I appreciate the multidisciplinary nature of the MBWC where I can have informed and nuanced discussions not only with behavioral neurologists, but also geriatricians, geriatric psychiatrists, and neuropsychologists. Everyone is focused on the disease that I’m trained to manage. I value my time in the clinic and have spent hundreds of hours leading the charge to offer the drug lecanemab at the University of Washington. I’m also in the process of running a program known as Partners in Dementia that pairs up people living with early-stage Alzheimer’s with first-year medical students in the setting of a buddy program.

In the field of behavioral neurology, it is important that one engages in activities that foster innovation. I feel like MBWC physicians are positioned to perform research that can change the way we think about and manage dementia. I’m honored to be connected with researchers who are experts in their fields, such as creating better biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. It’s also refreshing that there is an established infrastructure for clinical trials. There’s no ceiling on what you can do here.

What does it feel like to work in this field in the wake of the FDA approval of anti-amyloid therapies for Alzheimer’s disease?

It has been a tough road for someone specializing in behavioral neurology, where most of your patients have incurable neurodegenerative diseases and the medications that you have to prescribe them have very limited impact on disease progression. We have been waiting for the moment when there are disease-modifying drugs that not only lower amyloid levels in the brain but also slow decline in cognition and function. We have reached that moment, and it is an absolute dream to be able to help the MBWC prepare to administer this drug and drugs that have the similar mechanisms of action.

What is your perspective on the message of some in the field who point out that the benefit of lecanemab is limited for people living with Alzheimer’s disease?

I think the amount of progress we’ve made in the past couple of years has been greater than the amount of progress in the field over the past decade. It’s one of the fastest moving periods in terms of innovation that I can remember as a specialist. I liken the emerging Alzheimer’s drugs to the drugs that were developed to treat cancer. In the 1950s, drugs such as methotrexate and similar agents had horrible side effects and resulted in modest improvements in terms of morbidity and mortality in these patients. But it was the start of something bigger. And now, over 50 years later, our perspective on cancer is much different. I think this is where we are with Alzheimer’s disease, and this is an initial step.

There are going to be similar drugs that will be refined over time, such that they are more efficacious, have fewer side effects, and can be more easily administered. In addition, I think there will be drugs of different mechanisms that, when combined with anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies, will have synergistic effects in persons with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. There has also been a lot of exciting work on blood-based biomarkers over the past five years or so. I can see a future where the primary care doctor can draw blood and confirm the presence of an Alzheimer’s process, thus facilitating the earlier identification of patients who are likely to go on to develop dementia.

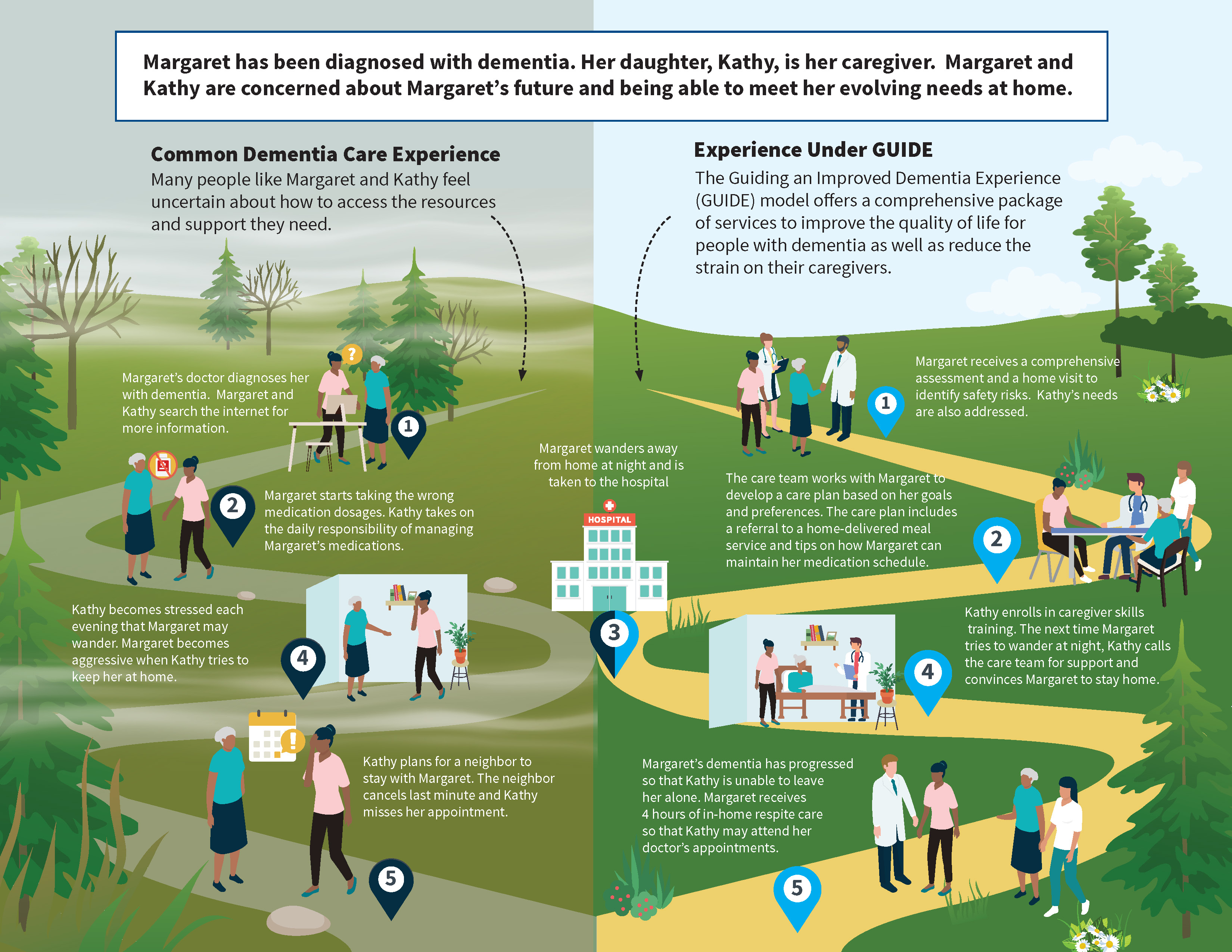

Your most recent publication is focused on the care ecosystem, a collaborative dementia care model that provides personalized, cost-efficient support for persons living with dementia and their caregivers. This telephone and web-based intervention was developed and studied at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center via an award from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation and the National Institutes of Health. Your research showed that a care ecosystem can be incorporated in a memory clinic and offers many advantages. Can you tell us how you think a care ecosystem model could innovate dementia care and improve quality of life?

Let’s consider the current process of diagnosis and care at the MBWC. A patient is referred by their primary care doctor or they may get a direct referral depending on their insurance. At the first clinic visit, they get a workup that involves medical history, lab exams, imaging, and potentially some biomarker assessment. At a follow up appointment, the doctor goes over the different pieces of the puzzle and renders a diagnosis and a care plan. The patient may be referred to our MBWC social worker for any psychosocial issues. There are patients who, over time, may require more attention than a single visit with a social worker. There may be issues related to behaviors or wandering from the home, or a family member may need help navigating the system for transitions to residential care. It is a journey for every patient and family dealing with Alzheimer’s disease. However, our social work capacity is limited because thousands of patients are followed at the MBWC, and we have one social worker on the team.

However, a care ecosystem provides a way to supplement the clinic social worker’s eyes and ears. In a care ecosystem, people called ‘care team navigators’ are trained by the social worker, and then provide regular telephone support to those families who have the greatest need. Those families receive a patient-specific care plan that addresses caregiver needs and concerns, and they are followed over time. With a program like the care ecosystem, outcomes are better for both the patient and the caregivers.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has released a request for applications to implement a model called Guiding an Improved Dementia Experience (GUIDE). This is an opportunity for other institutions, such as ours, to receive federal funding to implement what is tantamount to a care ecosystem model. We are pursuing this opportunity and hope to bring this model to the MBWC clinic. •

Source: CMS.gov