Genevieve Wanucha, MBWC

The Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care published a report on July 31, 2024 that highlights recommendations for policy makers and individuals to help reduce dementia risk worldwide. This report, which is being presented to researchers gathered at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC 2024), presents new evidence that untreated vision loss and high LDL cholesterol are risk factors for dementia.

The Commission is authored by 27 dementia experts from different countries. The author list includes the UW ADRC’s Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH, who is affiliate professor of medicine in the UW School of Medicine, who has now worked on all three Lancet reports on dementia risk.

“For me, it's been a labor of love because it is the opportunity to compile the best evidence with the world's leading experts,” says Larson.

The new report outlines these recommendations for individuals and governments to help reduce risk:

- Provide all children with good quality education and be cognitively active in midlife.

- Make hearing aids available for all those with hearing loss and reduce harmful noise exposure.

- Detect and treat high LDL cholesterol in midlife from around age 40 years.

- Make screening and treatment for vision impairment accessible for all.

- Treat depression effectively.

- Wear helmets and head protection in contact sports and on bikes.

- Prioritize supportive community environments and housing to increase social contact.

- Reduce exposure to air pollution through strict clean air policies.

- Expand measures to reduce smoking, such as price control, raising the minimum age of purchase, and smoking bans.

- Reduce sugar and salt content in food sold in stores and restaurants.

“For the first time, the report emphasizes that the onset of dementia can be delayed and the duration that people suffer from dementia can be shortened,” says Larson. “From a socioeconomic point of view, these estimates of risk reduction are cost effective. There’s a real reason to believe that if we invest as society and as individuals in ways to reduce our risk, the payoff is worth the cost. And to me, that's very interesting.”

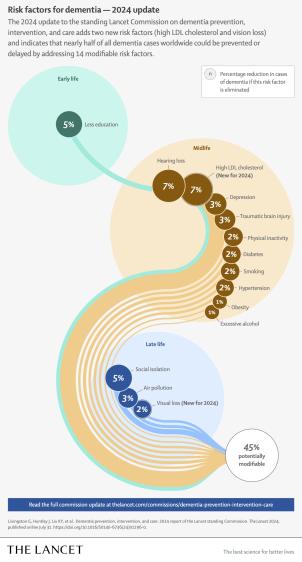

Based on the latest available evidence, the new report adds two new risk factors that are associated with 9% of all dementia cases —with an estimated 7% of cases attributable to high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) or “bad” cholesterol in midlife from around age 40 years, and 2% of cases attributable to untreated vision loss in later life.

These new risk factors are in addition to 12 risk factors previously identified by the Lancet Commission in 2020, including lower levels of education, hearing impairment, high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury, air pollution and social isolation which are linked with 40% of all dementia cases.

“What’s unique about the third report, in my opinion, is that, as opposed to relying on individual studies, it relies on meta-analyses, or syntheses of multiple studies, to come up with these estimates,” says Larson. “The report also tries to explain the mechanism by which there might be a reduction in risk. And we hadn't done that before.”

The report amasses the newest research findings to demonstrate the high potential to prevent and better manage dementia if action to address these risk factors begins in childhood and continues throughout life, even in individuals with high genetic risk for dementia.

“What amazes me is how much more evidence there is now and how much more robust and convincing the evidence is for using a life course approach to modify the risk of dementia in late life,” says Larson. “This has always been a premise for some of us on the Commission, but it's clearly been more accepted worldwide now. I think University of Washington can lay claim to being a serious player in this change.”

This report, as well as the two prior reports, is influenced by research at the University of Washington, particularly studies on the role of exercise and treatment of cataracts and hearing impairment in dementia prevention.

“It's a good idea to reduce hearing impairment, if possible,” says Larson. “It’s also a good idea to do what you can to either prevent or treat vision impairment, especially due to cataracts, so that the sensory input to the brain is as good as possible. Sensory input seems to nourish the brain and promotes social interaction, which taken together seems to delay the onset of dementia.”

Larson believes that rates of dementia can and have gone down in places with where various risk factors have been ameliorated. The rate of dementia means the number of cases of dementia developing each year. As proof-of-concept, the rates of dementia have gone down for people born later in the 20th century in America and England, because of better education, socioeconomic status, reduced vascular risk and health care, he notes.

But there is much more that can be done to reduce the risk of dementia, according to the report’s lead author Professor Gill Livingston from University College London, UK. “It’s never too early or too late to take action, with opportunities to make an impact at any stage of life,” she says. “We now have stronger evidence that longer exposure to risk has a greater effect and that risks act more strongly in people who are vulnerable. That’s why it is vital that we redouble preventive efforts towards those who need them most, including those in low- and middle-income countries and socio- economically disadvantaged groups. Governments must reduce risk inequalities by making healthy lifestyles as achievable as possible for everyone.”

This article is based on an interview with Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH, and contains material from the Lancet press release and report text.